Continuing Education Activity

Bruxism, characterized by involuntary rhythmic contractions of the masseter muscles and excessive teeth grinding, is a commonly overlooked yet significant condition. Symptoms can manifest during wakefulness or sleep and encompass primary and secondary forms. Sleep-related bruxism, associated with normal sleep arousals and various underlying medical conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea, Down syndrome, and medication effects, can cause considerable damage to teeth and dental work, resulting in morning jaw pain or fatigue, temporal headaches, and restricted motion of the temporomandibular joint. Although the diagnosis is primarily clinical, some patients with suspected sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea require polysomnography. Clinicians utilize a comprehensive treatment approach encompassing counseling, lifestyle management, oral devices, and medication management to address bruxism.

Through this evidence-based review, healthcare professionals explore the latest advancements in understanding the causes of bruxism, including its multifactorial nature, pathophysiology, and clinical manifestations. By examining prevalence rates and associated risk factors, participants recognize the importance of identifying and managing bruxism in clinical practice, particularly its implications for detecting potential sleep disorders, its impact on oral health, temporomandibular joint function, patient outcomes, and overall quality of life. By fostering collaboration and communication among healthcare professionals, participants gain the skills to coordinate efforts in the management of bruxism, ultimately enhancing their ability to deliver patient-centered care, improve diagnostic precision, and optimize treatment outcomes for individuals affected by this prevalent condition.

Objectives:

Identify the clinical manifestations and risk factors associated with bruxism.

Implement evidence-based treatment modalities for managing bruxism, including behavioral techniques, oral devices, and pharmacotherapy.

Assess the effectiveness of interventions in reducing bruxism-related symptoms and complications.

Collaborate with other healthcare professionals, such as dentists, sleep specialists, and physical therapists, to optimize interdisciplinary care for patients with bruxism.

Introduction

Bruxism, a prevalent condition, involves rhythmic contractions of the masseter muscles, accompanied by teeth grinding and mandible thrusting. Bruxism can manifest during sleep or wakefulness, each with various contributing factors.[1] Sleep bruxism is most common in children, affecting 15% to 40% of children and 8% to 10% of adults. Wake bruxism affects 22.1% to 31% of the population. The underlying cause is likely a centrally mediated phenomenon related to microarousals from sleep and activation of the autonomic nervous system.[2][3][4]

Clinicians categorize bruxism as primary or secondary based on its association with underlying medical conditions. In severe cases, bruxism may cause considerable damage to teeth and dental work, leading to morning jaw pain, temporal headaches, and restricted motion of the temporomandibular joint. Generally, the diagnosis is clinical, but affected patients require a thorough evaluation to identify potential underlying sleep disorders or other associated risk factors. Healthcare professionals utilize a multifaceted treatment approach focusing on patient education, counseling, lifestyle modification, and dental appliances.

Anatomy and Physiology

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of bruxism is related to the circadian phase. Sleep bruxism, a sleep-related movement disorder, is believed to be regulated by the central nervous system, involving autonomic and brain activity related to arousal or alertness.[5][6][7] Sleep bruxism appears to be an exaggerated oromotor response to natural sleep-related microarousals distinguished by a rise in autonomic cardiac and respiratory activity occurring 8 to 14 times per hour during sleep. Seconds before these episodes, affected patients demonstrate rapid-frequency cortical electroencephalogram activity, heart rate elevation, increased jaw and oropharyngeal muscle tone, and increased respiratory effort and nasal airflow.[8]

Awake bruxism is often associated with stress and heightened alertness, which can lead to increased autonomic cardiac activity. Awake bruxism presents as masticatory muscle activity during wakefulness, where repetitive or sustained tooth contact is associated with mandibular bracing or thrusting.[5] This activity is not considered a movement disorder in otherwise healthy patients.[5]

Risk Factors

Sleep apnea and anxiety are the most common risk factors associated with sleep bruxism.[3]

Genetics

Studies reveal that hereditary factors can contribute to bruxism.[9] Around 20% to 50% of patients with bruxism report at least 1 family member with bruxism. A genome-wide association study reveals a significant correlation between the rs10193179 variant of the Myosin IIIB gene (MYO3B) and sleep bruxism.[10]

Sleep Disorders

Restless leg syndrome, periodic limb movement during sleep, sleep-related gastroesophageal reflux disease, rapid eye movement behavior disorder, and sleep-related epilepsy are all associated with sleep bruxism. Other than rapid eye movement behavior disorder and Parkinson's disease, sleep arousal appears to be the common factor linking all of these disorders.[11]

Approximately 50% of adults with obstructive sleep apnea have comorbid sleep bruxism.[12] The bruxism episode index is positively associated with the apnea-hypopnea index in patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea, defined as an apnea-hypopnea index of <30 events/h.[13] Some researchers propose that sleep bruxism may play a protective role during respiratory-related arousal.

Medications

The use of amphetamines, antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors, noradrenaline-dopamine reuptake inhibitors, and drugs of abuse with catecholaminergic effects such as cocaine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine can be associated with sleep bruxism.[14] However, research is unclear whether these chemicals worsen preexisting bruxism or cause primary bruxism.

Neurologic and Psychiatric Disorders

Additional linked neurologic and psychiatric disorders associated with sleep bruxism include anxiety, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, multiple system atrophy, traumatic brain injury, Down syndrome, Rett syndrome, cerebral palsy, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Stimulants used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder may partially underlie the condition's relationship to bruxism.

Additional Substances and Circumstances

Heavy alcohol use, excessive caffeine consumption, tobacco use, and highly stressful life circumstances also contribute to bruxism.[15]

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of bruxism is primarily clinical and relies on a thorough evaluation, utilizing self-reports or input from a bed partner alongside the clinical examination.[5] Self-reports offer insight into potential bruxism activity and frequency but lack details on the intensity and duration of muscle activity.[5] A large study reveals that 8% of participants report teeth grinding during sleep weekly, with approximately 50% reporting daytime symptoms such as facial muscle discomfort.[9] Typically, clinicians reserve polysomnography for cases where suspected comorbid sleep disorders are present. Nevertheless, suspected bruxism warrants a comprehensive assessment and identification of potential risk factors.

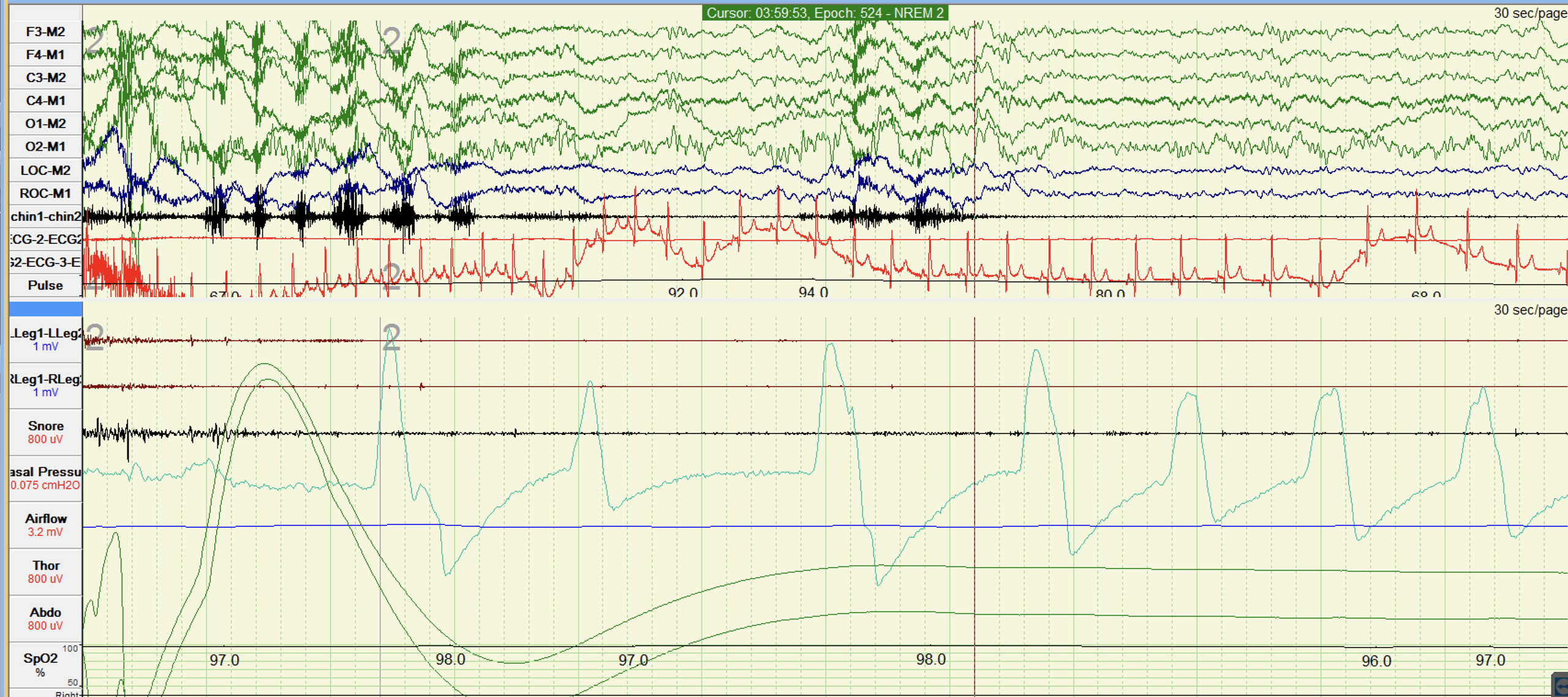

EMG recordings may help in diagnosing both awake bruxism and sleep bruxism. However, relying solely on EMG recordings for diagnosing bruxism can be unreliable.[5] During sleep, EMG recordings may also be supplemented by other methods used in polysomnography (see Image. Polysomnographic Record During Sleep), including audio and video recordings. Specifically, EMG can identify phasic episodes, defined by brief and rhythmic muscle contractions, typically identified when at least 3 contractions lasting between 0.25 and 2.0 seconds occur, accompanied by 2 or more intervals of no contractions. On the other hand, a single muscle contraction persisting for longer than 2 seconds distinguishes tonic or sustained episodes. If both patterns occur, the pattern is considered a mixed episode.[7] The most common EMG pattern associated with sleep bruxism is rhythmic masticatory muscle activity.

The diagnostic criteria for sleep bruxism, as outlined by the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition (ICSD-3), include the following:[16]

- Repetitive jaw-muscle activity characterized by grinding or clenching of the teeth during sleep

- The presence of 1 or more of the following clinical signs or symptoms consistent with the report of tooth grinding or clenching during sleep

- Abnormal tooth wear

- Transient morning jaw muscle pain or fatigue

- Temporal headache

An application-based assessment that provides personal information about muscle activity while awake can offer additional evidence of the behavior in patients with awake bruxism.[5]

International experts also suggest a grading system for diagnosing awake bruxism and sleep bruxism. This system places patients into 1 of 3 possible categories.

- Possible bruxism: The diagnosis is possible when based on self-reporting only.

- Probable bruxism: The diagnosis is probable based on self-reporting and clinical examination.

- Definite bruxism: The diagnosis is definite when clinicians incorporate self-reporting, clinical inspection, and polysomnographic recording, ideally accompanied by audio and video recordings.

Indications

Intermittent bruxism is prevalent, particularly among children. Often, patients remain asymptomatic, and treatment is not warranted.[17] Typically, clinicians treat bruxism when adverse effects on oral structures occur or in the presence of concurrent conditions such as neurological or sleep disorders or those listed below.

- Mechanical wear of the teeth causing the loss of occlusal morphology and flattening of the occlusal surfaces

- Hypersensitive teeth

- Fractured teeth

- Fractures of restorations, crowns, and partial prosthesis

- Failure of dental implants

- Masticatory muscle hypertrophy

- Tenderness and stiffness in jaw muscles

- Restricted opening of the mouth

- Temporomandibular joint pain

- Preauricular pain

- Clicking and tenderness of the temporomandibular joint

- Headaches due to temporalis muscle tightness and tenderness

- Unpleasant loud noises during sleep that cause sleep disturbances [18][19]

Contraindications

Obstructive sleep apnea is a contraindication to the use of an occlusal splint. Occlusal splints can worsen obstructive sleep apnea. Patients with sleep bruxism and obstructive sleep apnea who need protection for their teeth should use a mandibular advancement device. Oral devices should be avoided in patients with epilepsy, as the device can serve as a foreign object in the airway during a seizure. Refer to the Technique or Treatment section for more information regarding occlusal splints and mandibular advancement devices.

Technique or Treatment

Treatment for bruxism focuses on preventing additional tooth damage and relieving associated symptoms. The effectiveness of available treatments varies considerably.[17] Although orthodontic interventions are a potential option due to the proposed association between bruxism and malocclusion, this idea lacks consensus among dental professionals and supporting evidence from clinical studies.[18]

Managing sleep bruxism encompasses a range of approaches, including counseling and various medical or mechanical interventions. Treatment options include occlusal devices, behavioral interventions, and pharmacological therapies. Healthcare professionals should recognize and manage existing risk factors, particularly comorbid obstructive sleep apnea. Patients with suspected obstructive sleep apnea should undergo a formal sleep assessment and receive treatment with positive airway pressure if present. Appropriate treatment of obstructive sleep apnea alone may reduce the frequency of sleep bruxism episodes.[20]

Counseling

Experts propose counseling regarding sleep hygiene, habit modification, and relaxation techniques as the initial step in the therapeutic intervention of sleep bruxism. Sleep hygiene counseling is generally considered a safe and good practice. However, evidence supporting its efficacy is limited.[21] Avoidance of alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco before bedtime is considered necessary for maintaining good sleep, as sleep bruxism is associated with sleep arousal. In addition, patients with obstructive sleep apnea may require counseling on lifestyle modification, particularly addressing obesity.[17]

Behavioral Intervention

Biofeedback utilizes positive feedback to enable patients to learn tension reduction.[18] Other behavioral interventions and acupuncture may offer short-term relief from the pain associated with bruxism.[22]

Oral Devices

Bite guards, preferably made from hard acrylic resin, cover upper or lower teeth. A dental clinician can fit them to protect teeth from damage due to bruxism and reduce teeth grinding.[23] Current data reveal that oral devices do not reduce the frequency of bruxism. However, patients report they decrease morning jaw discomfort, and they do effectively control tooth wear.[23][24]

Appliances vary in appearance and features. They may be constructed in the dental office or a laboratory and fabricated from hard or soft materials. Hard acrylic-resin stabilization splints are more effective compared to soft splints. Soft-resin splints are more difficult to adjust compared to hard acrylic-resin devices and may increase clenching behavior in some patients.[25] Studies reveal that some patients may have increased EMG activity when they wear an occlusal splint during sleep, particularly when the splints are soft or do not fit well.[17] Soft devices purchased over the counter should be avoided or used under the supervision of a dentist. Evidence reveals that these devices cannot be formed correctly without the proper training.[26]

Patients with comorbid obstructive sleep apnea and bruxism should utilize a mandibular advancement device to help reduce bruxism-related motor activity. Mandibular advancement devices induce mandibular advancement, increasing upper airway cross-sectional area and volume. Dental clinicians do not use mandibular advancement devices for isolated bruxism without obstructive sleep apnea.

Pharmacological Therapies

In refractory cases, drugs such as clonazepam 0.5 mg and clonidine 0.1 mg may inhibit bruxism, but the evidence is limited. Other therapies, such as the dopamine agonist pramipexole, reveal no improvement in the number of bruxism episodes compared to no treatment.[27][28][29] Hormone therapy may improve sleep bruxism in women experiencing menopause, likely due to a decreased number of arousals due to hot flashes. Because insufficient evidence exists regarding the efficacy of these medications, experts cannot recommend them for routine use.

Other Investigational Therapies

Botulinum toxin A injections in the masseter and temporal muscles every 6 months may provide improvement for patients with severe bruxism or movement disorders.[30] The injections decrease the strength of jaw muscle contractions but do not decrease the incidence of sleep bruxism events. A clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of occlusal guards and botulinum toxin injections for managing sleep bruxism demonstrates that both occlusal appliances and botox injections significantly improve patient satisfaction and sleep quality.[31] However, healthcare professionals should exercise caution when using botulinum toxin due to limited evidence and potential for adverse effects.

Contingent electrical stimulation intends to decrease masticatory muscle activity by applying low-level electrical stimulation when the muscles responsible for bruxism become active.[21] However, further studies are necessary to elucidate long-term results.

Healthcare professionals address AB through various techniques such as habit modification, cognitive behavioral therapy, exercise, relaxation therapy, and biofeedback.[32] Appropriate treatment may also involve appliance therapy after excluding organic causes such as medications and concurrent medical conditions. Clinicians should contemplate medication withdrawal or substitution in cases of medication or drug-induced bruxism, ensuring safety in medication changes. For individuals involved in recreational drug use or excessive alcohol intake, clinicians should provide comprehensive patient education and treatment for substance use disorder.[19][33] As with sleep bruxism, patients are also advised to abstain from nighttime caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol consumption.[17]

Complications

Potential complications of bruxism treatment include malocclusion, dental carries due to improper dental hygiene, temporomandibular disorders, and teeth staining. In addition, some occlusal devices only cover the anterior teeth. When the posterior teeth erupt in children wearing this type of device, they can develop an anterior open bite where a lack of overlap or contact between maxillary and mandibular incisors exists, while the posterior teeth are in occlusion. This development leads to unnecessary orthodontic interventions.

Clinical Significance

When occlusal forces exceed the body's adaptive capacity, a stomatognathic breakdown occurs, leading to complications such as tooth wear, hypersensitivity, mobility, temporomandibular joint or jaw muscle pain, headaches, gingival recession, and disrupted sleep.[34][35][36][35] In addition, it can pose challenges during dental prosthesis construction and placement.[37] Bruxism is also associated with technical challenges when constructing and placing a dental prosthesis.[37] Affected patients can experience migraine, neck pain, insomnia, and depression.

Sleep bruxism occurs in 36.8% of preschoolers and over 40% of children in the first grade.[38] A study indicates that sleep bruxism in children is associated with increased health problems and increased internalizing behaviors such as being anxious, depressed, withdrawn, and expressing somatic complaints. Increased frequency of health problems is, in turn, associated with decreased neurocognitive performance. As health problems increase, neurocognitive performance decreases, raising the possibility that sleep bruxism in children is an indicator of current or future adverse health conditions and the need for early intervention.[38]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bruxism is widespread during sleep and wakefulness, characterized by rhythmic contractions of the masseter muscles and teeth grinding. Depending on its association with underlying medical conditions, it can manifest as primary or secondary, with various factors contributing to its development. Sleep-related microarousals correlate with sleep bruxism, whereas stress and heightened alertness often cause awake bruxism. Risk factors include sleep apnea, anxiety, genetic predisposition, sleep disorders, medication use, and neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Given the diverse range of potential underlying comorbidities, effective care coordination necessitates integrating services across healthcare settings and disciplines, ensuring smooth transitions and continuity of care.

The diagnosis primarily relies on clinical evaluation, although polysomnography may be necessary for patients suspected of having sleep disorders. Treatment focuses on preventing tooth damage and easing associated symptoms. Clinicians employ counseling and behavioral interventions to encourage patients to abstain from substances such as alcohol, caffeine, and tobacco, especially before bedtime. Clinicians may also recommend lifestyle modifications or medication adjustments as needed. Additional treatment options encompass oral devices, pharmacological therapies, and investigational treatments such as botulinum toxin injections. Addressing comorbid obstructive sleep apnea is paramount for affected patients.

A collaborative approach involving physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, dental clinicians, and other healthcare professionals is essential for enhancing patient-centered care. Each healthcare team member contributes unique skills and expertise to the care process. By harnessing their skills, adopting collaborative strategies, promoting interprofessional communication, and coordinating care effectively, healthcare professionals can improve overall patient outcomes, reduce healthcare costs and morbidity, and elevate team performance in managing bruxism.