Introduction

Viral hepatitis, a significant health care burden worldwide, is defined as virally mediated liver inflammation. Numerous viruses are known to cause liver inflammation, including but not limited to, Epstein-Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus, and Cytomegalovirus. However, the hepatotropic viruses, termed A to E, are the most common culprits. Most of the hepatotropic viruses are acute and self-limiting, although forms B, C, and E have the potential to become chronic. Various genotypes of the viruses exist, with some being more prominent in specific geographical locations than others.

Furthermore, different genotypes have varying rates of seroconversion to chronic hepatitis and respond better to specific treatments versus others.[1] Chronic hepatitis can lead to severe complications, namely cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma.[2] Viral hepatitis and its complications result in approximately 1 to 4 million deaths per year worldwide, by one estimate. The vast majority of deaths are caused by Hepatitis B and C. Treatment goals differ depending on the pathogen, but broadly include prevention of transmission, eradication, and suppression.[3] The World Health Organization has responded to the expanding burden of disease by developing "The Global Strategy for Viral Hepatitis," which outlines their goals aimed at preventing further transmission and providing access to care for those currently living with the disease.[3]

Etiology

The hepatotropic viruses are by far the most common causes of viral hepatitis. All of them are RNA viruses except for Hepatitis B, which is a DNA virus. Hepatitis A and E are transmitted via the fecal-oral route, whereas Hepatitis B, C, and D are primarily blood-borne.[3]

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is typically transmitted by contamination of water and food by the feces of an infected individual. Poor personal hygiene is a risk factor.[3]

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is unique in that it can be transmitted vertically. Other modes of transmission include sexual contact via semen and vaginal secretions, through blood via injection drug use or unsafe medical practices, and even via close person-to-person contact.[4]

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was a major adverse event associated with blood transfusions before its characterization and the development of blood screening protocols. The main modes of transmission today are through drug use (intravenous or intranasal), contaminated healthcare injections, and through sexual contact. The transfusion-associated transmission does still occur in resource-poor nations.[5][6]

Hepatitis D virus (HDV) is similar to HBV and HCV because it is mainly transmitted via blood or sexual contact. However, HDV is unique among the other viruses because it requires the HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) to replicate and is dependant on it.[7]

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is also most commonly transmitted by contamination of water and food, and less frequently by the zoonotic route or via transfusion.[8]

Epidemiology

HAV mainly occurs sporadically and occasionally, causing epidemics. Endemic regions are historically the developing nations with poor sanitary conditions. Natives are typically infected in childhood and tend not to experience symptoms. They become immune and can avoid re-infection later in life. However, individuals native to developed countries with adequate sanitary conditions are at risk when they travel to endemic areas due to lack of exposure in early life. These populations experience significantly more severe symptoms because they tend to be adolescents or adults with more robust immune systems. Fulminant hepatitis generally does not occur. Endemic regions include Africa, Asia, as well as South and Central America.[3]

The highest burden of HBV infection is seen in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Western Pacific.[9] In nations with high rates of chronic HBV infection, transmission typically occurs vertically or in early childhood. This is the time when the chance of seroconversion to chronic disease is highest. Evidence suggests that women of childbearing age are at peak infectivity in high-prevalence areas due to the predominant genotypes of those lands. In areas of intermediate- or low-prevalence, where different genotypes persist, there is not a high level of infectivity in women of childbearing age. Therefore, the incidence of perinatal and childhood infection, as well as chronic disease, decreases from areas of high prevalence to those of low prevalence. The vast majority of infections occurring in low-prevalence areas occur in adolescents or adults through sexual contact, intravenous drug use, and healthcare-associated accidents.[4]

The distribution of HCV infection among varying age groups is dependent on the region in focus. For example, the incidence of infection is highest among individuals aged 30 to 49 in the United States, mostly via injection drug use.[6] Still, individuals aged 50 and greater have the highest incidence of infection in other nations. The highest burden of HCV infection is seen in Africa and Asia.[10]

The leading group at risk for HDV infection is those with chronic HBV infection. Interestingly enough, the geographic distribution of HDV differs from that of HBV. Endemic regions include the Middle East, Asia, Africa, the Amazonian basin, and the Pacific islands. Recent evidence has found that the highest incidence is among those aged 20 to 39 years of age, specifically in the Amazonian Basin.

Much like hepatitis A, most HEV endemic regions are developing nations with poor sanitary conditions. The virus can be acquired from ingesting raw or poorly cooked animal products, not only in resource-poor areas but in industrialized countries where these types of foods are considered a delicacy. Additionally, infected mothers can pass the virus onto the fetus, although the incidence is low. A transfusion-related infection has also been reported. Hepatitis E virus infection in pregnant women is of particular concern. Both the incidences of disease and fulminant hepatic failure are higher in the pregnant population when compared to age-matched men and non-pregnant women. Areas with a high incidence of infection include Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Central America.[8]

Pathophysiology

Whether a virus gains entry via the blood or the enteric system, it eventually travels to the liver where it enters hepatocytes, replicates, and sheds virions. Replication occurs via either direct translation of viral RNA or via reverse transcription of viral DNA.[11] Hepatocyte injury can be acute and self-limited or insidious and chronic. The mechanism of hepatocyte injury is mediated by the host immune response to viral antigens that are expressed by infected hepatocytes and not so much by cytopathic effects of the viruses themselves.[12] The progression to chronic infection observed with HBV and HCV is associated with attenuation of virus-specific T-cells. Studies have shown that exhaustion of these virus-specific T-cells leads to an inability to clear the viruses, therefore allowing the viruses to dwell chronically in host hepatocytes.[13]

Histopathology

A biopsy is usually not done for acute viral hepatitis. Biopsies are done if there clinical suspicion of a second independent hepatic insult such as underlying chronic liver disease or if there are unusual infectious processes in immunocompromised patients. All forms of acute hepatitis show lobular disarray. This includes ballooning degeneration, spotty necrosis, Kupffer cell hyperplasia, canalicular cholestasis, hepatocellular regeneration, sinusoidal and lobular mononuclear cell infiltrate, and scattered apoptotic bodies.

History and Physical

Historical clues indicating viral hepatitis infection include recent travel to endemic areas, parenteral exposure (intravenous drug use, blood transfusion before 1992), and close or sexual contact with individuals known to have hepatitis or who are suffering from jaundice. Patients should always be asked about immunosuppressive state and organ transplants, as well as exposure to raw meat.

Patients may report fever, anorexia, malaise, nausea, vomiting, right upper quadrant fullness or pain, jaundice, dark urine, and pale stools. Some patients are asymptomatic, while others may present with fulminant liver failure.

The physical examination may reveal scleral icterus or jaundice, hepatomegaly, and right upper quadrant tenderness.

Evaluation

Laboratory testing commonly reveals elevated aminotransferases and elevated bilirubin. Acute hepatitis typically presents with aminotransferase levels measured in the 1000’s. Chronic hepatitis varies in presentation with aminotransferase levels typically elevated to no more than 2 times to 10 times the upper limit of normal.[14]

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used in the diagnosis of acute and chronic viral hepatitis.

HAV: IgM antibody is diagnostic for acute infection. IgG positive but IgM negative indicates past exposure.

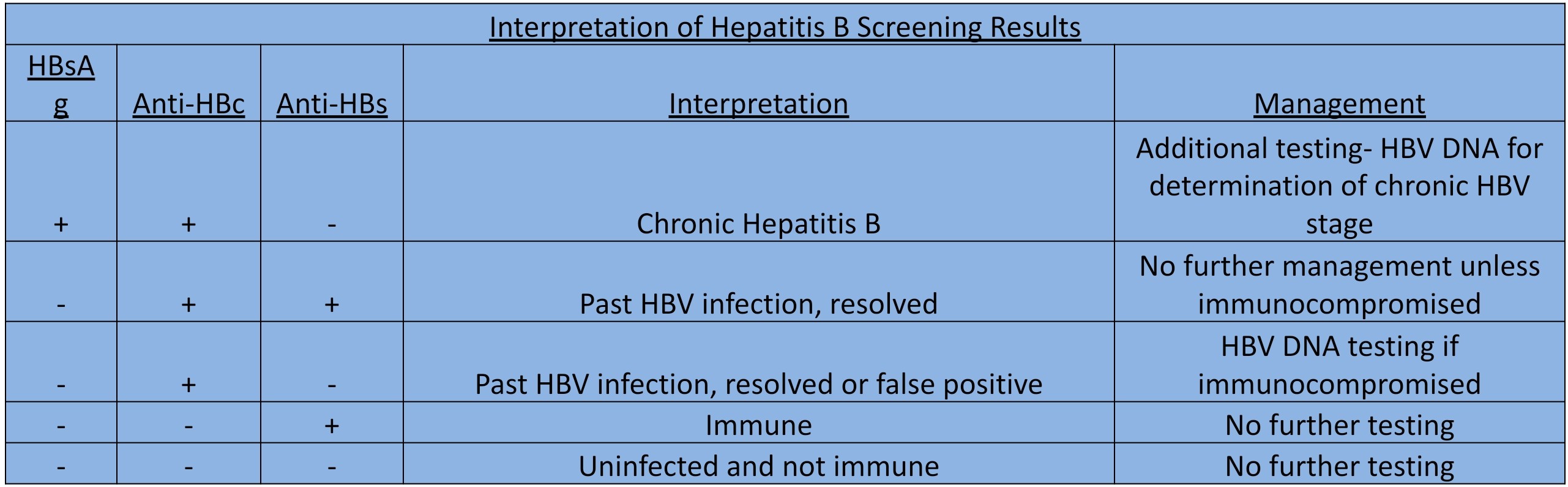

HBV: Acute infection is indicated by the presence of surface antigen, IgM core antibody, envelope antigen, and viral load. However, there is also a “window period” during which the surface antigen disappears before the appearance of IgG antibody to surface antigen. Chronic HBV infection is denoted by the presence of surface antigen for longer than 6 months, IgG core antibody, and HBV DNA, plus the absence of surface antibody.

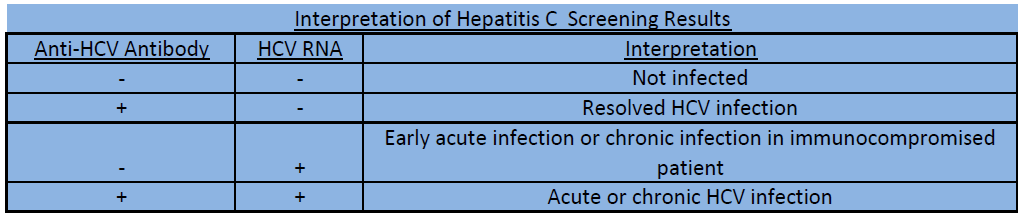

HCV: Acute infection is indicated by the presence of HCV RNA with or without the presence of IgM antibody. Chronic infection is indicated by the presence of HCA RNA with the presence of the IgG antibody. If a patient clears the infection, results will show no detectable HCV RNA, with or without the presence of HCV antibodies.

HDV: Antibodies indicate exposure to the virus while the viral load is used to detect current infection.

HEV: IgM is indicative of acute infection, as are HEV antigen and RNA viral load. RNA viral load is also used to evaluate response to anti-viral therapy. IgG confirms vaccine efficacy or natural protection.

Treatment / Management

HAV is managed supportively and commonly resolves on its own.

Treatment of acute HBV infection is mainly supportive; however, unique sub-populations require treatment with antiretrovirals. These subpopulations include individuals who are symptomatic, who have elevated bilirubin greater than 3 mg/dl for more than four weeks, who develop coagulopathy, and those who develop acute liver failure. Antiretroviral choices include monotherapy with tenofovir, entecavir, lamivudine, or telbivudine.[15] The decision to treat chronic infection depends on multiple factors which can be reviewed in the HBV specific review topic.

Direct-acting antivirals (DAA’s) are the treatment of choice for HCV infection. However, different genotypes respond better to certain DAA’s than others. Furthermore, the decision to treat a patient at the presentation of acute infection versus monitoring to see if the disease becomes chronic and then treating is another issue. This will be explained in the HCV specific review topic.

The management of acute HDV infection is mainly supportive. Furthermore, though significant data is lacking, pegylated interferon alpha seems to be the treatment of choice in patients requiring treatment for chronic HDV infection.

HEV is usually self-limited in immunocompetent individuals, with viremia lasting only about three weeks. In the case of acute and self-limiting illness, supportive care with replenishment of vitamins and symptomatic treatment of cholestasis is the mainstay. Ribavirin is used to treat chronic HEV infection, most commonly in solid organ transplant populations.[16]

Lastly, viral hepatitis infections resulting in fulminant hepatic failure require immediate transfer to a liver transplant center for evaluation of liver transplantation.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of viral hepatitis includes other forms of hepatitis, such as ischemic, toxic injury, acute biliary obstruction, alcohol use disorder, and autoimmune processes. Acute ascending cholangitis is another consideration.

Treatment Planning

Monitoring and follow-ups during the treatment period are extensive, and therefore, treatment planning should involve a gastroenterologist or a hepatologist. Furthermore, although there are now treatments available that are pan-genotypic, genotype testing is usually still performed to tailor and individualized treatment plans.

Prognosis

HAV is a relatively brief illness. Only a minimal number of patients with acute HAV infection go on to develop fulminant hepatic failure. Furthermore, the HAV vaccine results in almost 100% protection. There is a rare relapsing-remitting presentation of HAV that tends to resolve spontaneously within one year and does not require any intervention other than supportive care.

Acute HBV infection has a less than 1% chance of causing acute liver failure. Older adults, those with preexisting liver disease, and the immunocompromised tend to have more severe infection compared to others. Additionally, Less than 5% of immunocompetent adults will become chronic carriers, making the risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma relatively low.[17] Vaccination has resulted in a significantly decreased burden of disease.

The risk of seroconversion to chronic hepatitis C infection is estimated to be approximately 75% to 85%. This confers a much higher risk of developing cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma as a result. However, with the advent of DAA’s, over 90% of chronic HCV infected patients can achieve sustained viral clearance.

HDV coinfection and superinfection result in a faster rate of progression to cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Vaccination helps to prevent super-infection.

HEV is usually a short illness in immunocompetent patients. It can cause prolonged viremia, chronic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, and cirrhosis in individual immunocompromised patients, including those with solid organ transplants, positive HIV status, and those with leukemia and lymphoma.[8]

Complications

The most feared complication of acute viral hepatitis is liver failure. It is called fulminant hepatitis at times and necessitates an immediate liver transplant.

Chronic viral hepatitis can result in cirrhosis and all of the complications associated with cirrhosis, including increased risk for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Consultations

Hepatology, gastroenterology, and infectious disease specialists are usually consulted.

Deterrence and Patient Education

All patients should be educated on risk factors for transmission, including travel to endemic areas, promiscuous sexual practices, and intravenous and intranasal drug use. Furthermore, patients should be informed of the vaccines available to prevent disease.

Pearls and Other Issues

New guidelines endorsed by the United States Preventive Services Task Force indicate screening for Hepatitic C virus infection in all adults aged 18 to 79 even without a history of significant exposure or risk factors.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

To improve the prevention of viral hepatitis, one should enhance the knowledge of healthcare providers, especially outpatient-based providers. This knowledge should encompass viral hepatitis screening and vaccination strategies.