Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is also known as Osler–Weber–Rendu disease. It is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by multiple mucocutaneous telangiectasias. These telangiectasias represent small arterio-venous malformations that frequently tend to bleeds causing the patient a significant amount of distress in their daily lives. Patients typically present with nose bleeds, gastrointestinal (GI) bleeds, and iron deficiency anemia. This disease puts patients at risk for life-threatening complications from having arteriovenous malformations in several organ systems. It is critical for these patients to get the appropriate diagnostic screening they need to prevent internal bleeding or even death.

Etiology

There are 2 main types of HHT that are both caused by heterozygous mutations. HHT1 involves a mutation in endoglin (ENG). With this type, patients, especially women, are at a higher risk of getting pulmonary and cerebral AVMs. HHT2 involves a mutation in activin A receptor-like type 1 (ACVRL1), also known as ALK1. Patients with HHT2 have a higher risk of getting liver AVMs. ENG comprises about 61%, and ACVRL1 comprises about 37% of the mutations known to cause HHT. Mutations in growth differentiation factor 2 (GDF2) have been found. These encode the protein that binds to endoglin and ACVRL1. Lastly, there are mutations in SMAD4 which encodes a protein that transmits signals from the transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) receptor. This mutation only comprises about 2% of cases. Patients with this gene mutation get juvenile GI polyposis and HHT.[1][2]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of HHT is 1.5 to 2 persons/10,000; although, some sources say that it is higher due to variable penetrance and because symptoms do not present until later in adult life. HHT has a higher prevalence in certain populations, such as the Afro-Caribbean residents of Curacao and Bonaire.[3]

Pathophysiology

The mutations found in HHT disrupt TGF-beta-mediated pathways in vascular endothelial cells. Disruption in this pathway results in aberrant blood vessel development leading to extreme fragility and arteriovenous malformations.

Histopathology

The histopathology description of telangiectasias is characterized as having dilated capillaries lined with flat endothelial cells. AVMs are characterized as having a mixture of thick and thin-walled vessels in the dermis.

History and Physical

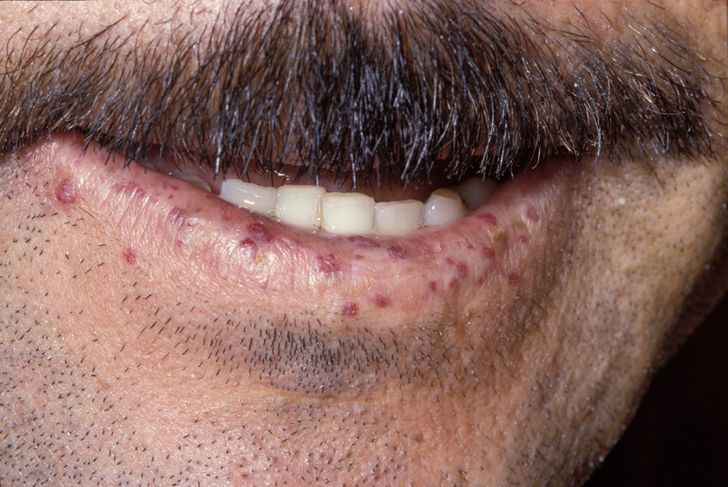

The primary and most common manifestation of HHT is usually epistaxis that begins during childhood or adolescence at a mean age of 12 years. Telangiectasias do not usually appear until after puberty but may not occur until adulthood. They typically occur on the face, lips, tongue, palms, and fingers including the periungual area and the nail bed. Telangiectasias are dilated blood vessels that appear as thin spiderweb-like red and dark purple lesions that blanch with pressure. AVMs are abnormal connections between arteries and veins that bypass the capillary system. Patients with HHT have multiple AVMs throughout the body. However, the most important AVMs for which clinicians should screen are in the brain, lungs, GI tract, and liver. AVMs in the lung and brain can be asymptomatic.[4]

Pulmonary AVMs can cause hypoxemia, hemorrhage, and cerebral abscesses or strokes due to paradoxical emboli. They can lead to the right to left shunting in approximately 15% to 50% of HHT patients.

Cerebral AVMs can lead to lethal intracranial hemorrhage starting from infancy. They occur in 25% of HHT patients.

Spinal AVMs can occur in children and can cause acute paraplegia.

GI bleeding can occur from AVMs and typically occurs in adults in their 40s. Patients often present with iron deficiency anemia.

Liver AVMs can lead to high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and biliary disease. They present in 30% to 80%, but they are symptomatic in less than 10% of patients.[1]

Evaluation

If 3 or more clinical criteria are met, then the individual has definite HHT. If they only meet 1 or 2 criteria, then HHT is suspected. The clinical criteria are spontaneous recurrent epistaxis, characteristic mucocutaneous telangiectasias, visceral telangiectasias/AVMs, and HHT in a first-degree relative. More than 90% of patients with HHT will meet these criteria by 40 years of age.

Because of the life-threatening complications that can occur in a patient who has visceral AVMs, it is important to order the appropriate diagnostic tests.

- Pulmonary AVMs: Transthoracic contrast echocardiography should be ordered. If negative, repeat screening should be considered after puberty, within the 5 years preceding a planned pregnancy, after pregnancy, and otherwise every 5 to 10 years. This test is indicated for either suspected or confirmed HHT. If positive, confirmation with high-resolution thoracic CT should be performed.

- Brain AVMs: Brain MRI with and without gadolinium should be ordered for suspected and confirmed HHT.

- Liver AVMs: Screening via doppler ultrasound or triphasic helical CT is recommended in all patients with HHT and abnormal liver enzyme tests or clinical evidence of complications from liver AVMs, including high-output heart failure, portal hypertension, and cholestasis.

- Anemia: Annual blood tests to look at hemoglobin and hematocrit levels should be completed in HHT patients over 35 years old.

- Genetic analysis: A screen for ENG and ACVRL1 ± SMAD4 and/or GDF2 should be done in those that are at risk because of an affected first-degree relative or are clinically suspected to have HHT.[1][5]

Treatment / Management

Transcatheter embolotherapy is recommended for all adults and symptomatic children with pulmonary AVMs, and on a case-by-case basis for asymptomatic children. Treatment strategies for AVMs of the central nervous system (CNS) include embolization, microsurgery, and stereotactic radiation. If brain AVMs are found the patient, he or she should be referred to a neurovascular surgeon for management as treatment for these is highly controversial. Acute GI bleeds should be managed according to hospital protocol. GI AVMs can be managed with endoscopic cauterization. Hormonal or antifibrinolytic therapy may be used as adjunct therapy to prevent ongoing bleeding. In patients that have liver AVMs, embolization is not recommended given the risk post-embolization necrosis and death. Surgical intervention should only be considered if they become symptomatic or develop complications. For those with significant hepatic AVM involvement, partial liver resection is a safe treatment option. If a patient’s hemoglobin and hematocrit are low, an upper endoscopy should be completed if the anemia is disproportionate to epistaxis. Iron supplementation should be initiated, either oral or intravenous (IV) and endoscopic cauterization can be considered. It is recommended that acute epistaxis be managed with low-pressure, less-traumatic packing techniques. In some studies, a mild benefit was shown for the use of humidifiers to prevent chronic epistaxis, and there have been no controlled trials comparing more definitive surgical techniques such as nasal artery embolization or coagulation techniques.[1]

Differential Diagnosis

Some differential diagnoses are CREST syndrome, spider angiomas, Ataxia-Telangiectasia, Bloom syndrome, Rothmund syndrome.

Prognosis

Most HHT patients who have adequate access to healthcare will have normal life expectancies. There is a bimodal distribution of mortality, with peaks at age 50 and then from 60 to 79. Most of the mortality of HHT is the result of complications of AVMs, particularly in the brain, lungs, and GI system.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) result in a significant amount of distress in the daily lives of patients and their families. This disease puts patients at risk for life-threatening complications. It is critical for these patients to get the appropriate diagnostic screening they need to prevent internal bleeding or even death and have an interprofessional team of clinicians and specialty trained nurses assisting in the coordination of follow-up care. This will result in the best patient outcome. [Level V]