[1]

Lamb LC, DiFiori M, Comey C, Feeney J. Cost Analysis of Direct Oral Anticoagulants Compared with Warfarin in Patients with Blunt Traumatic Intracranial Hemorrhages. The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):1010-1014

[PubMed PMID: 29981640]

[2]

Daher P, Teixeira PG, Coopwood TB, Brown LH, Ali S, Aydelotte JD, Ford BJ, Hensely AS, Brown CV. Mild to Moderate to Severe: What Drives the Severity of ARDS in Trauma Patients? The American surgeon. 2018 Jun 1:84(6):808-812

[PubMed PMID: 29981606]

[3]

Harvell BJ, Helmer SD, Ward JG, Ablah E, Grundmeyer R, Haan JM. Head CT Guidelines Following Concussion among the Youngest Trauma Patients: Can We Limit Radiation Exposure Following Traumatic Brain Injury? Kansas journal of medicine. 2018 May:11(2):1-17

[PubMed PMID: 29796153]

[4]

Abolfotouh MA, Hussein MA, Abolfotouh SM, Al-Marzoug A, Al-Teriqi S, Al-Suwailem A, Hijazi RA. Patterns of injuries and predictors of inhospital mortality in trauma patients in Saudi Arabia. Open access emergency medicine : OAEM. 2018:10():89-99. doi: 10.2147/OAEM.S166026. Epub 2018 Jul 31

[PubMed PMID: 30104908]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[6]

Thierauf-Emberger A, Lickert A, Pollak S. A moving human body causes fatal blunt trauma: an unusual traffic accident. International journal of legal medicine. 2019 Mar:133(2):547-551. doi: 10.1007/s00414-018-1855-z. Epub 2018 Jun 6

[PubMed PMID: 29876635]

[7]

George E, Khandelwal A, Potter C, Sodickson A, Mukundan S, Nunez D, Khurana B. Blunt traumatic vascular injuries of the head and neck in the ED. Emergency radiology. 2019 Feb:26(1):75-85. doi: 10.1007/s10140-018-1630-y. Epub 2018 Aug 10

[PubMed PMID: 30097750]

[8]

Joachim M, Tuizer M, Araidy S, Abu El-Naaj I. Pediatric maxillofacial trauma: Epidemiologic study between the years 2012 and 2015 in an Israeli medical center. Dental traumatology : official publication of International Association for Dental Traumatology. 2018 Apr 27:():. doi: 10.1111/edt.12406. Epub 2018 Apr 27

[PubMed PMID: 29701325]

[9]

Leetch AN, Wilson B. Pediatric Major Head Injury: Not a Minor Problem. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2018 May:36(2):459-472. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2017.12.012. Epub 2018 Feb 10

[PubMed PMID: 29622334]

[10]

Essien EO, Fioretti K, Scalea TM, Stein DM. Physiologic Features of Brain Death. The American surgeon. 2017 Aug 1:83(8):850-854

[PubMed PMID: 28822390]

[13]

Masterson Creber RM, Dayan PS, Kuppermann N, Ballard DW, Tzimenatos L, Alessandrini E, Mistry RD, Hoffman J, Vinson DR, Bakken S, Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) and the Clinical Research on Emergency Services and Treatments (CREST) Network. Applying the RE-AIM Framework for the Evaluation of a Clinical Decision Support Tool for Pediatric Head Trauma: A Mixed-Methods Study. Applied clinical informatics. 2018 Jul:9(3):693-703. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1669460. Epub 2018 Sep 5

[PubMed PMID: 30184559]

[14]

McGrew PR, Chestovich PJ, Fisher JD, Kuhls DA, Fraser DR, Patel PP, Katona CW, Saquib S, Fildes JJ. Implementation of a CT scan practice guideline for pediatric trauma patients reduces unnecessary scans without impacting outcomes. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2018 Sep:85(3):451-458. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001974. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29787555]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence

[15]

Bukur M, Teurel C, Catino J, Kurek S. The Price of Always Saying Yes: A Cost Analysis of Secondary Overtriage to an Urban Level I Trauma Center. The American surgeon. 2018 Aug 1:84(8):1368-1375

[PubMed PMID: 30185318]

[16]

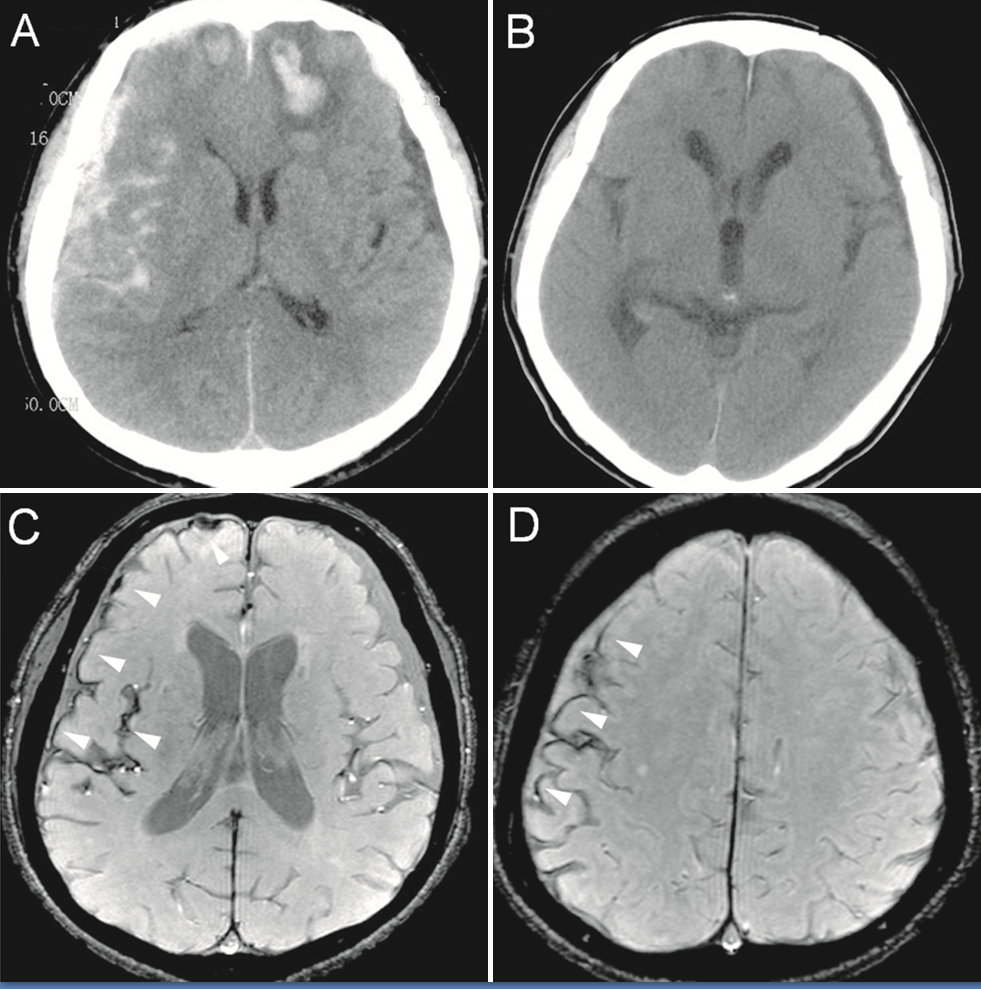

Rybkin I, Kim M, Amin A, Tobias M. Development of Delayed Posttraumatic Acute Subdural Hematoma. World neurosurgery. 2018 Sep:117():353-356. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.135. Epub 2018 Jun 26

[PubMed PMID: 29959076]

[17]

McLoughlin RJ, Green J, Nazarey PP, Hirsh MP, Cleary M, Aidlen JT. The risk of snow sport injury in pediatric patients. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2019 Mar:37(3):439-443. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.06.006. Epub 2018 Jun 2

[PubMed PMID: 29884589]

[18]

Khor D, Wu J, Hong Q, Benjamin E, Xiao S, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Early Seizure Prophylaxis in Traumatic Brain Injuries Revisited: A Prospective Observational Study. World journal of surgery. 2018 Jun:42(6):1727-1732. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4373-0. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29159600]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[19]

Watanabe T, Kawai Y, Iwamura A, Maegawa N, Fukushima H, Okuchi K. Outcomes after Traumatic Brain Injury with Concomitant Severe Extracranial Injuries. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2018 Sep 15:58(9):393-399. doi: 10.2176/nmc.oa.2018-0116. Epub 2018 Aug 11

[PubMed PMID: 30101808]

[20]

Aiolfi A, Khor D, Cho J, Benjamin E, Inaba K, Demetriades D. Intracranial pressure monitoring in severe blunt head trauma: does the type of monitoring device matter? Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Mar:128(3):828-833. doi: 10.3171/2016.11.JNS162198. Epub 2017 May 26

[PubMed PMID: 28548592]