Introduction

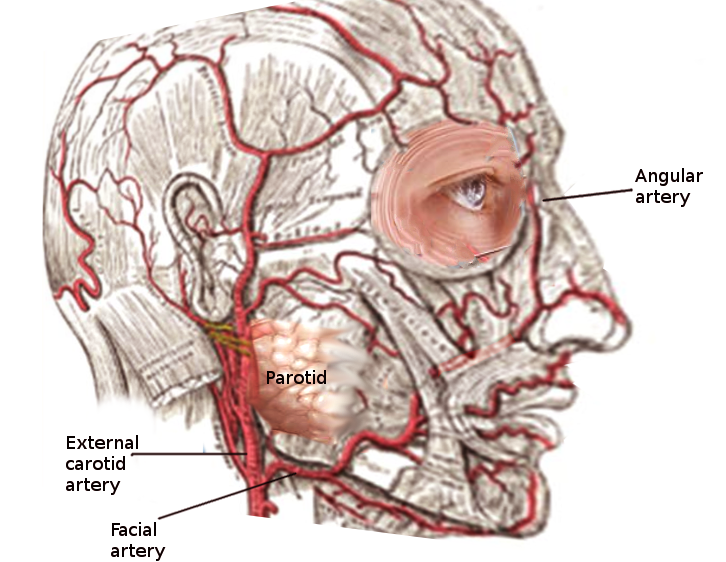

The facial artery is a major vessel originating from the external carotid artery (ECA) that primarily supplies the face's superficial structures (see Image. Facial Artery). This artery ascends from the neck to the face, traversing significant anatomical landmarks, such as the mandible and the mouth's angle.

Clinically, the facial artery's palpable pulse at specific points along its course serves as a vital diagnostic tool for healthcare professionals, aiding in the assessment of circulatory health and facilitating accurate diagnoses of vascular conditions. In surgical contexts, the facial artery's precise anatomical knowledge is paramount during cervicofacial procedures. Surgeons rely on a thorough understanding of this vessel's course to navigate safely during operations, minimizing the risk of inadvertent damage and ensuring optimal outcomes. Understanding the facial artery's anatomy and function is essential in treating various cervicofacial disorders.

Structure and Function

Structure

The facial artery has a cervical division that gives rise to 4 other vessels before supplying the face. The facial artery's cervical branches include the ascending palatine, tonsillar, submental, and glandular branches. Meanwhile, the main vessels arising from the facial artery's trunk include the inferior and superior labial, lateral nasal (supplies the nasalis), and angular arteries.[1] The angular artery is the facial artery's terminal segment.

The facial artery originates from the carotid triangle and is bordered by the omohyoid (superior belly), sternocleidomastoid, and digastric muscle (posterior belly).[2] The facial artery emerges from beneath the platysma before coursing superficially. The vessel's notable tortuous trajectory accommodates facial movements like mastication that produce dynamic cervicofacial stretching.

The facial artery navigates underneath the posterior digastric belly and stylohyoid in its ascent across the facial region. Afterward, the vessel courses along the submandibular gland's posterior aspect, arches over the mandibular body, and advances along the masseter's anteroinferior border. The artery's passage near the mandible is clinically significant due to its palpable pulse at this site.[3]

The facial artery continues its journey superiorly at an oblique angle across the cheek. Afterward, the vessel approaches the oral commissure, ascends adjacent to the nasal sidewall, and culminates at the medial eye canthus, where it continues as the angular artery. This elaborate pathway underscores the facial artery's essential function in facial vascularization and integration within the head and neck's broader circulatory system.[4]

Function

The facial artery branches out to numerous structures, supplying facial expression muscles such as the buccinator and levator anguli oris. Additionally, the artery's path may intersect with or pass over the levator labii superioris (a normal variant).[5] The facial artery also provides circulation to the levator veli palatini, masseter, mentalis, mylohyoid, nasalis, palatoglossus, palatopharyngeus, platysma, procerus, risorius, styloglossus, transverse nasalis, palatine tonsils, soft palate, pterygoids, digastrics, and submandibular gland.

Embryology

Human arterial development begins around the 19th day of gestation, with longitudinal channels forming paired dorsal aortae. The heart tubes fuse by days 21 to 25, and the ventral aortic sac remains connected to the dorsal aortae via the 1st primitive aortic arch (PAA). The 1st and 2nd PAAs disappear on day 29. By day 32, 6 pairs of PAAs are present. Regression between the 3rd and 4th PAAs occurs around 6 weeks or at an embryo size of 12 to 14 mm.

Studies show that a portion of the right primitive ventral aorta between the 4th and 6th PAAs forms the brachiocephalic trunk and a part of the aortic arch. The common origin of the right 3rd and 4th PAAs also elongate to form the brachiocephalic trunk. The right subclavian artery persists from the right 4th PAA's proximal part, while the left 4th PAA contributes to the left common carotid artery (CCA). The right CCA develops from the brachiocephalic trunk, and new branches from the 3rd PAAs' ventral aspects form the ECAs, along with portions of the 1st and 2nd arch arteries. The 3rd PAA transforms into the carotid sinus and forms the internal carotid artery (ICA) with the cranial dorsal aorta. Meanwhile, the cranial ventral aorta becomes the ECA, which gives rise to the facial artery.[6][7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The facial artery diverges from the ECA near the deep superior cervical lymph nodes. The submandibular lymph nodes lie adjacent to the facial artery as the vessel courses toward the face superficially. The submandibular and facial lymph nodes remain deep to this artery as it crests over the mandibular body.

Nerves

The hypoglossal nerve travels deep to the proximal facial artery. The facial artery often traverses deep to the facial nerve's marginal mandibular branch.[8]

Muscles

The facial artery arises deep to the platysma in the neck, eventually becoming superficial. The vessel then traverses superior to the stylopharyngeus, styloglossus, and hyoglossus before traveling inferior to the posterior digastric belly and stylohyoid. The facial artery enters a groove on the submandibular gland's posterior surface and follows an upward trajectory over the mandibular body as it courses along the masseter's anteroinferior border. The facial artery remains superficial to the buccinator and levator anguli oris muscles in the face.

Physiologic Variants

The facial artery can have many anatomical variations similar to other vessels in the body. This artery may arise as a single vessel from the linguofacial trunk or the rarer thyrolinguofacial trunk. The vessel may also arise from either the ICA or CCA in the absence of an ECA.[9] Deviations from the facial artery's ascent near the lip areas can impact surgical planning in midfacial procedures such as cleft-lip repair.[10] Other clinically significant variations include facial artery enlargement, hypoplasia, and agenesis.

Surgical Considerations

Procedures Involving the Facial Artery

The facial artery is critical to facial reconstructive procedures, as it can act as the vascular supply for various flaps, including local, regional, or free flaps. Common flaps using the facial artery include the submental, platysmal, nasolabial, buccinator myomucosal, and facial artery musculomucosal flaps.[11] These types of reconstructive procedures can be performed following head and neck tumor resections. The robust facial artery can adequately supply grafted tissue.

Complications Associated with the Facial Artery

The facial artery is vulnerable to injuries during various surgical procedures, requiring a careful approach to avoid vascular trauma. Excessive retraction in this area should be prevented. Facial artery hemorrhage can occur during submandibular gland excision, necessitating ligation during external approaches to mandible fracture repair.[12] Any ligations performed require detailed documentation in the operative note for future reference. Facial artery bleeding may be addressed by applying direct pressure to the mandibular angle over the vessel until hemostasis is achieved.

The facial artery also abuts many nerves, including the hypoglossal. Early identification and trauma avoidance minimize post-operative complications.

Clinical Significance

The facial artery's pulse is typically palpable at the masseter's anteroinferior angle against the mandible's bony surface, where it runs superficially. However, strong pulsations of the angular artery, the facial artery's terminal branch, may be appreciated in around 70% of cases where the ICA is occluded. The angular artery connects with the infraorbital artery's medial branches externally and the ophthalmic artery's dorsal nasal and supratrochlear branches internally through anastomotic channels. However, the diagnostic significance of this finding is limited, as the angular artery palpability without ICA occlusion is normal in only 1 out of 10 adults older than 55 with long-standing hypertension.[13]

CCA atherosclerosis increases the risk of head and neck embolic events, leading to ischemic injury. Facial artery occlusion may lead to superficial facial muscle weakness. Rarely, CCA emboli may travel and cause ischemic injury to distal facial artery branches.