Continuing Education Activity

Seborrheic keratosis is a common type of epidermal tumor that is prevalent in middle-aged and older individuals. These lesions are among the most common types of skin tumors seen by primary care physicians and dermatologists in an outpatient setting. Although seborrheic keratoses are benign tumors often presenting with distinguishing features, there can be some morphological overlap with other malignant skin lesions. Recognizing these features is critical to distinguishing these lesions from other benign and malignant skin tumors. Due to the benign nature of seborrheic keratosis, treatment is often not required. However, a majority of patients still opt to undergo some degree of treatment. Given the prevalence of these tumors, it is important to understand the workup and various treatment modalities for seborrheic keratosis management. This activity outlines the general evaluation and workup of seborrheic keratoses in the outpatient setting and discusses common features of seborrheic keratosis as well as various treatment modalities that are available for the interprofessional team.

Objectives:

Identify the common history and physical examination findings in a patient with seborrheic keratosis.

Apply evidence-based best practices when diagnosing seborrheic keratosis.

Differentiate the various treatment modalities for seborrheic keratosis in the outpatient setting.

Collaborate with an interprofessional healthcare team to improve care coordination and enhance the outcomes of patients with seborrheic keratosis.

Introduction

Seborrheic keratosis is a prevalent benign skin condition made up of immature epidermal keratinocytes.[1][2] The condition manifests in different forms, ranging from a faintly colored, superficial patch to a brown to black, scaly papule or plaque with a distinctive "stuck-on" appearance. Seborrheic keratoses are primarily seen in adults and older individuals. Most patients typically observe their initial seborrheic keratosis during their middle adult years. They exhibit gradual growth in both size and quantity over several years. This condition becomes more common as individuals age, and it affects almost all adults who are 60 years of age or older.[3]

Etiology

The benign proliferation of immature keratinocytes causes seborrheic keratosis, resulting in well-demarcated, round, or oval, flat-shaped macules. These lesions are typically slow-growing, can increase in thickness over time, and rarely resolve spontaneously.

Epidemiology

Seborrheic keratosis is the most common benign skin tumor, affecting over 80 million Americans.[4] Individuals older than 50 years of age typically develop seborrheic keratosis, which becomes more pronounced as they age. Although seborrheic keratoses are more common in middle-aged and older patients, they can also be present in young adults. There is no difference in prevalence between males and females. However, seborrheic keratosis appears more frequently in populations with lighter skin tones.

Pathophysiology

Seborrheic keratosis is caused by the benign clonal expansion of epidermal keratinocytes. There is believed to be a genetic component to the development of a high number of seborrheic keratoses. However, the exact familial inheritance is not known. The exact pathogenesis of this skin condition is also not known at this time, but there is a possible correlation with multiple abnormalities as follows:

- In cases of sporadic seborrheic keratosis, activating mutations in the tyrosine kinase receptor known as fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 (FGFR3) are common and are believed to be what drives the growth of this benign tumor.[5]

- Seborrheic keratoses have been discovered to contain somatic activating mutations in the TERT and DHPH3 promoters, but with a lower frequency.[6] Their significance in seborrheic keratosis development, however, remains unknown.[7]

- UV radiation exposure increases the expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) in skin locations, and this expression also rises with age. The expression of APP has been assessed in seborrheic keratoses compared to normal skin using immunohistochemistry, Western blotting, and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). The expression of APP and its downstream component, amyloid-β42, was more pronounced in seborrheic keratoses compared to the paired adjacent normal skin tissues. On the other hand, the level of expression of its primary secretase, specifically β-secretase 1, was minimal. The results indicate that an excessive amount of APP could accelerate seborrheic keratosis development and serve as an indicator of skin aging and damage caused by UV radiation.[8]

- Seborrheic keratoses have been shown to often develop oncogenic mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway, which leads to a heightened sensitivity to Akt inhibition.

- FoxN1 is a newly discovered biomarker that indicates the presence of an oncogenically active yet noncancerous phenotype in seborrheic keratoses.[9]

Histopathology

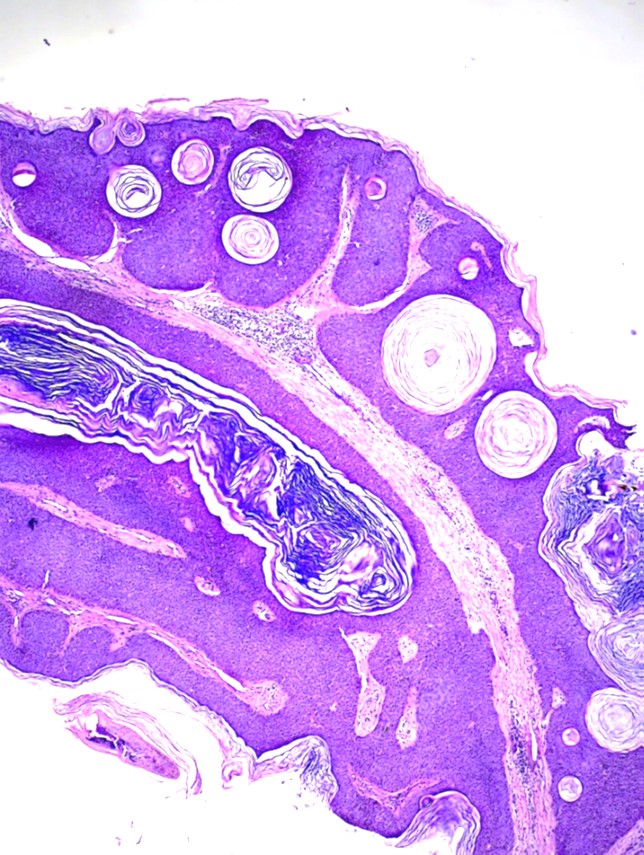

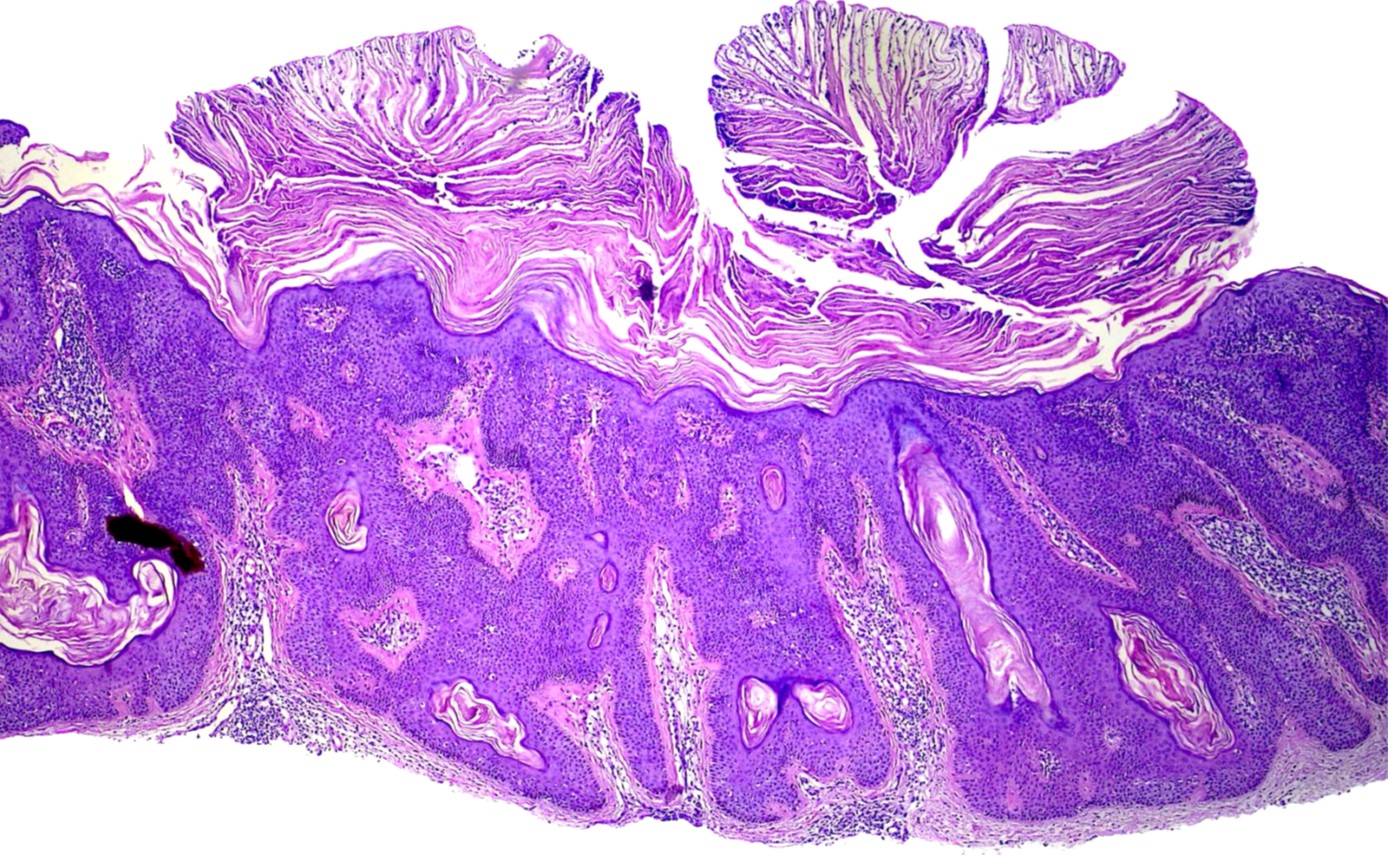

Under a microscope, seborrheic keratosis would typically show a proliferation of keratinocytes with keratin-filled cysts.[10] There can be lymphocytic infiltration present in inflamed or irritated lesions. Depending on the subtype, there can be varying degrees of hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, pseudocysts, hyperpigmentation, inflammation, and dyskeratosis, although 1 subtype is typically dominant in each lesion. Due to the high prevalence of this skin condition, it is crucial to biopsy those patients with atypical features and a higher clinical index of suspicion for malignancy. Seborrheic keratoses exhibit significant clinical diversity. However, even at the histologic level, numerous distinct subtypes can be identified: hyperkeratotic type, acanthotic type, reticular/adenoid type, clonal type, irritated type, melanoacanthoma, and verrucous seborrheic keratosis with keratoacanthoma-like features.

Acanthotic type

This type is the most frequently observed and is characterized by the pronounced acanthosis of basaloid cells predominately. The presence of moderate papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis is noted. Numerous horny invaginations appear as "pseudo-horn cysts" on cross-sections. Additionally, "true horn cysts" are observed, characterized by abrupt and total keratinization with a thin granular layer. Melanocytic proliferation and hyperpigmentation accompany a third of these lesions (see Image. Seborrheic Keratosis Histopathology 1). Occasionally, lesions in sun-exposed areas develop into an in-situ carcinoma of this type, known as "bowenoid transformation."[11]

Hyperkeratotic type (papillomatous)

This variety is characterized by marked hyperorthokeratosis and papillomatosis (see Image. Seborrheic Keratosis Histopathology 2). It can form a cutaneous horn.[5]

Reticular or adenoid type

The seborrheic keratoses of this subtype are characterized by thin, double rows of reticular acanthosis with mild to moderate hyperkeratosis and papillomatosis. Frequently, these seborrheic keratoses exhibit hyperpigmentation. Horn pearls are rare. This subtype is more prevalent in regions that receive direct sunlight.[12]

Clonal type

Clonal seborrheic keratosis is defined by the existence of 2 separate basaloid cell clones. One appears as nests of cytologically distinct keratinocytes that expand the stratum spinosum between the normal acanthotic epidermis. Approximately 50% of clonal seborrheic keratoses exhibit cytologic atypia, and there is a rare occurrence of these seborrheic keratoses progressing to cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in situ.[13] This particular type exhibits mild acanthosis, papillomatosis, and orthohyperkeratosis. Tumor cells are spindle-shaped. With a demarcated tumor, islands of basaloid cell nests are found. Pagetoid Bowen disease is a notable differential diagnosis for clonal seborrheic keratosis. In certain instances, immunohistochemistry may be useful for differentiating between the 2 entities. In clonal seborrheic keratosis, cytokeratin-10 expression is higher. There are more Ki-67-positive cells and over 75% positive p16 cells in Pagetoid Bowen disease.[14] Clonal seborrheic keratosis nests may exhibit patchy or diffuse p16 positivity. A p16 positivity in clonal nests of seborrheic keratoses without concurrent atypical histologic features is typical for seborrheic keratosis and not for pagetoid Bowen disease.[15]

Irritated type

Spindle-shaped eosinophilic tumor cells proliferate here, sometimes forming whorl-like formations (whorled squamous eddies). There is a possibility that dyskeratotic cells are present. It is crucial in clinical practice to distinguish between irritated seborrheic keratosis and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Immunohistochemistry can be useful in differentiating between the 2 entities. In routine clinical practice, a recent study found that the combination of U3 small nucleolar ribonucleoprotein protein IMP3 and B-cell lymphoma 2 regulatory protein (Bcl-2) can differentiate between irritated seborrheic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma. However, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) immunohistochemistry was not found to be useful in this context.[16]

Melanoacanthoma

This is the hyperpigmented acanthotic type with a proliferation of basaloid cells with mild or even absent hyperkeratosis. A multitude of melanocytes are interspersed with many melanophages situated in the dermis. Unlike common seborrheic keratoses, these lesions occur infrequently on the oral mucosa.[17]

Verrucous seborrheic keratosis with keratoacanthoma-like features

This is an uncommon subtype. One study estimated the frequency to be 0.8% of all keratoacanthomas. These lesions exhibit characteristic keratoacanthoma-like features, including a dome shape, marginal borders, a well-differentiated epidermis, and a crater with keratin plug formation, in addition to the classic histologic features of seborrheic keratosis. The presence of HPV16 was identified.[18][17]

Dermatosis papulosa nigra

Certain authors regard dermatosis papulosa nigra as a separate entity, yet the histology is indistinguishable from that of seborrheic keratosis.[19] The histological characteristics resemble those of reticular or acanthotic seborrheic keratoses. The lesions frequently contain FGFR3 mutations, just as seborrheic keratoses do.[20]

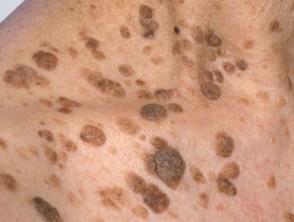

History and Physical

Clinically, seborrheic keratoses have a dull, waxy, verrucous surface, resulting in their characteristic "stuck-on" appearance. The color of these lesions can vary from light to dark brown, yellow, and grey, and they can present as an isolated lesion or as tens or even hundreds of lesions (see Images. Seborrheic Keratosis). These tumors can generally occur anywhere on the body except for the palms, soles, and mucous membranes. Seborrheic keratoses frequently aggregate on the face, scalp, trunk, inframammary folds, arms, and legs. Skin folds may exhibit pedunculation. The back may exhibit a "Christmas tree" pattern due to the distribution of lesions along Blaschko lines. Seborrheic keratoses rarely manifest any symptoms. However, pruritus and/or mild pain may be associated with inflamed or irritated lesions, particularly those situated in skin folds or subject to persistent irritation from clothing friction. Generally, seborrheic keratosis is benign, and its lesions are slow-growing; however, there should be concern if there is sudden growth or emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses. The sign of Leser-Trelat refers to the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratosis that is suggestive of internal malignancy commonly associated with gastrointestinal or pulmonary carcinomas.

Specific clinical variants of seborrheic keratosis include the following:

- Stucco keratoses are a collection of small, white, fine, adherent papules that can be observed in certain patients. These papules are commonly found on the dorsum of the feet and ankles. The classification of stucco keratosis as a subtype of seborrheic keratosis is controversial. Stucco keratoses are papillomatous keratoses that do not exhibit the presence of horn cysts and basaloid cells, which are commonly observed in seborrheic keratoses when examined histologically. Nevertheless, the 2 conditions exhibit comparable genetic mutations.

- An acanthotic variant of seborrheic keratosis known as dermatosis papulosa nigra may develop in patients with darkly pigmented skin. It is characterized by brown to black papules that increase in number with age and are predominantly found on the face and neck (see Image. Dermatosis Papulosa Nigra).

- The Leser-Trélat sign is characterized by the abrupt onset of multiple seborrheic keratoses, along with skin tags and acanthosis nigricans. This sign has been linked to various malignancies, such as gastrointestinal and lung cancers.

- The pseudo-Leser-Trélat sign is characterized by inflammation in preexisting seborrheic warts after chemotherapy for malignancies, specifically when employing medicines such as cytarabine, docetaxel, gemcitabine, or PD1 inhibitors like nivolumab. Commonly, patients report sensations of burning and itching. Continuation of tumor therapy is possible.[21]

Evaluation

The diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis is typically made through clinical observation. Seborrheic keratosis is characterized by its unique appearance as a raised, scaly, brown-to-black papule firmly stuck to the skin. This distinctive presentation allows experienced clinicians to easily identify the condition. Dermoscopy can aid in the clinical diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis. Common dermoscopic observations of seborrheic keratosis consist of comedo-like openings, milia-like cysts, gyri and sulci, and hairpin vessels (see Image. Dermoscopy of Seborrheic Keratosis). Features of melanocytic lesions, like pigment networks or globules, are absent in heavily pigmented seborrheic keratoses, though some typical dermoscopic features may be obscured. A lesion biopsy is typically unnecessary for diagnosing seborrheic keratosis. Nevertheless, in cases where the clinical or dermoscopic diagnosis is ambiguous, it is necessary to conduct a biopsy and histopathologic examination to rule out the presence of melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or basal cell carcinoma.

Additionally, seborrheic keratosis is slow-growing and can become larger and thicker over time. There have been cases of a secondary tumor growing adjacent to or within a preexisting seborrheic keratosis. A dermatologist referral should be considered for a more thorough and team-oriented approach in patients with a high number of lesions and high clinical suspicion of malignancy.

If there is uncertainty with the diagnosis or other concerns for malignancy, such as ulcerated lesions, rapid change in size, or overall very large lesions, a skin biopsy would be recommended to get confirmation.[22] Rapid growth and the emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses can arise in several situations. The Leser-Treélat sign involves the emergence of multiple seborrheic keratoses and is associated with underlying malignancies such as adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal tract, leukemia, and lymphoma.[23] For these individuals, performing a thorough history and physical examination, conducting age-appropriate cancer screening, and ordering additional labs based on risk factors and the patient's history is crucial. Chemotherapy and inflammatory dermatitis (eczema) are other causes of a sudden eruption of multiple seborrheic keratoses.

Treatment / Management

Various treatment modalities are available for the removal of seborrheic keratosis. Seborrheic keratosis is benign and typically does not warrant any treatment. Usually, seborrheic keratosis removal is for cosmetic reasons or lesions that are consistently irritated and cause discomfort for the patient.[24] Suspicious, bleeding, rapidly growing, or changing lesions carry a higher risk of malignancy and should be biopsied or removed. The choice of therapy should be individualized for the patient. Considerations should include the lesion size and thickness, the patient's skin type, clinical suspicion of malignancy, and the physician's clinical experience. Locally destructive treatments

Cryotherapy

The most common and readily available treatment for seborrheic keratosis is cryotherapy.[25] This method is efficacious and generally well tolerated by the patient. This method utilizes liquid nitrogen, or CO2, to rapidly freeze or thaw the targeted cells, resulting in cell death. There are currently no set guidelines for freezing or thawing times, and the times can vary depending on the thickness of the lesion. Thicker lesions may require multiple freeze/thaw cycles to effectively treat the area. Additionally, this treatment method does not permit any histologic confirmation and should only be used for low-risk lesions with a low clinical suspicion of malignancy. This method has a low post-procedure care regimen for the treated area; however, it can cause erythema, pain, and bulla formation. There have been some reports of post-procedure hypopigmentation or hyperpigmentation with the healing of these areas after therapy.

Electrodesiccation and curettage

Another method for removing seborrheic keratosis is electrodesiccation with or without curettage. This process is another option for removing superficial, epidermal lesions without invasion into the dermis. This technique usually requires the use of local anesthetics and can be performed in an office setting. This method uses the curette to scrape and remove the epidermal tissue, followed by electrodesiccation with a hyfrecator or cautery unit; this is typically performed multiple times to ensure adequate removal of the affected tissue. Curettage and desiccation (C&D) provides efficient results and generally has a low rate of complications. Possible complications of C&D include infection, scarring, and hyperpigmentation.

Ablative laser treatment

Laser therapy is another nonsurgical treatment option for patients with seborrheic keratosis. Two types of lasers are used to treat seborrheic keratosis: ablative and nonablative laser therapy. Ablative laser therapy includes YAG and CO2 lasers, and nonablative lasers (755 nm alexandrite laser) have been utilized for this purpose. Multiple small studies have shown some efficacy in treating seborrheic keratosis; however, further studies are necessary.

Shave biopsy

Another modality for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis is shave excisions. Typically, this treatment modality is for skin conditions primarily contained in the epidermis, without the involvement of the dermis. These procedures require some local anesthesia, usually 1% lidocaine with or without epinephrine, depending on the location of the lesion. A superficial excision is performed with a scalpel, special exfoliating blade, or double-edged razor blade to remove a thin slice of tissue containing the lesion. The specimen can then be sent to the laboratory to determine the exact pathology of the affected area. It is indicated for lesions that are not unequivocally diagnosed as seborrheic keratosis clinically and/or dermoscopically and require histopathologic examination.

A small intrapatient comparative study that included 25 adults examined the efficacy and patient satisfaction of cryotherapy or simple curettage for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. At 6 weeks, the mean patient ratings for cosmetic outcomes were similar for both procedures, though 15 of 25 patients (60%) preferred cryotherapy.[26] An additional investigation involving 33 patients randomly assigned 2 comparable seborrheic keratoses located on each participant's trunk to either electrodesiccation or cryosurgery. Twenty-five lesions (81%) in both intervention groups were deemed completely cleared by a clinician unaware of lesion assignment after 8 weeks. Patients' preferences for both procedures were comparable at the beginning, 2 weeks, and 8 weeks. Nevertheless, lesions that underwent electrodesiccation exhibited a higher propensity for residual hyperpigmentation at the 8-week mark compared to those that underwent cryotherapy.[27] A comparative study was conducted on 42 patients with multiple seborrheic keratoses on the face, neck, and trunk. The patients were treated either with an Er:YAG laser or cryotherapy. The results showed that laser treatment led to faster healing and less hyperpigmentation than cryotherapy.[28]

Topical agents

Researchers are currently studying various types of topical agents for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. Topical gels and creams used for hyperkeratotic skin conditions (such as tazarotene, imiquimod cream, alpha-hydroxy acids, and urea ointment) as well as vitamin D analogs (tacalcitol, calcipotriol) have been used for treating these lesions. While some studies have shown promising results in reducing or resolving seborrheic keratosis lesions, more research is necessary to assess the effectiveness of these topical medications.

Other topical agents for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis include diclofenac gel and potassium dobesilate. Diclofenac is a topical NSAID, and potassium dobesilate is an inhibitor of the FGF signaling pathway. These agents were used in small studies, and their efficacy is not well established.

The FDA recently approved a topical hydrogen peroxide solution for the treatment of seborrheic keratosis. In 2018, a randomized, double-blinded placebo control trial was conducted using a topical 40% hydrogen peroxide solution.[29][30] Overall, the application of topical hydrogen peroxide was well tolerated and effective in removing seborrheic keratosis. The adverse effects of treatment were generally mild and included erythema, scaling, and hyperpigmentation.

Seborrheic keratoses can be removed by an aqueous nitric-zinc combination. The mixture contains nitric acid, zinc, copper, and organic acids (acetic, lactic, and oxalic). This nitric-zinc combination was applied topically to seborrheic keratoses in a therapeutic experiment. The nitric-zinc solution was applied every other week until clinical and dermoscopic clearing or crust formation, up to 4 times. All subjects who reported no or moderate discomfort during and after solution administration finished the research. After 3 administrations per lesion, 37 of 50 lesions were cleared after 8 weeks. The remaining 13 lesions showed a partial response, with few remnant spots. All patients with full clearance had no relapses after 6 months.[31]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for seborrheic keratosis is broad and should include malignant melanoma, actinic keratosis, lentigo maligna, melanocytic nevus, squamous cell carcinoma, and pigmented basal cell carcinoma.[32] Overlapping lesions or high numbers of seborrheic keratosis can make the diagnosis and workup of these lesions more difficult. Again, patients with large numbers of seborrheic keratosis require careful screening, as there can be an increased chance of missing coexisting malignant lesions.

Differential diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis includes the following:

- Malignant melanoma: Although exceedingly uncommon, collision tumors and melanomas resembling seborrheic keratoses have been documented.[33][34][35] The clinical and dermoscopy-based diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis-mimicking melanoma is difficult. Notably, hyperkeratosis is not generally associated with melanoma, and most melanomas are superficial, spreading, and macular (flat) in appearance, whereas most seborrheic keratoses are raised, hyperkeratotic lesions. Melanoma is indicated by the presence of a pigment network, pseudopods or streaks, and a blue-white veil on dermoscopy.[34] Histologic and clinical examinations are crucial to accurately diagnose lesions that exhibit inconclusive clinical and dermoscopy characteristics.

- Pigmented seborrheic keratoses may be mistaken for pigmented actinic keratosis, pigmented basal cell carcinoma, or cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma when observed on the face and in sun-exposed areas. However, these lesions do not have the characteristic stuck-on appearance of seborrheic keratosis.

- Epidermal nevus

- Acanthosis nigricans

- Viral warts: Hyperkeratotic seborrheic keratoses and verruca vulgaris may exhibit substantial histologic and clinical overlap. Lesions exhibiting a seborrheic keratosis appearance in the genital or perineal region may often correspond to genital warts (condyloma acuminata). Therefore, human papillomavirus (HPV) typing and biopsies may be viable alternatives to empiric treatment involving destructive techniques. While the majority of seborrheic keratoses have a diameter <4 cm, there are instances where larger lesions form, leading to potential differential diagnoses such as Buschke-Löwenstein tumors.[36]

Prognosis

Seborrheic keratoses are benign lesions and have an excellent overall prognosis. The primary reason for treating seborrheic keratosis is cosmetic. Multiple treatment modalities have good outcomes with minimal adverse effects or complications. Patients with numerous seborrheic keratoses should be evaluated more carefully, as the high number of lesions can mask concomitant malignant lesions. Leser-Trelat is a sign of an internal malignancy that is associated with a worse prognosis.

Complications

Seborrheic keratoses are the most common type of benign skin lesions. They grow slowly but can become thicker over time. Depending on their location, these lesions can become irritated and cause pain and discomfort for the patient. Furthermore, large numbers of these lesions can make it more difficult to detect other malignant skin lesions. A case report has been published describing the transformation of seborrheic keratosis into bowenoid actinic keratosis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis who was treated with multiple immunosuppressants. Three distinct histological changes caused the transformation.[37]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Deterrence and patient education are pivotal aspects in the management of seborrheic keratosis. Clinicians play a crucial role in educating patients about the benign nature of seborrheic keratosis, dispelling concerns about malignancy, and emphasizing the importance of regular skin examinations for early detection of any changes. Patient education efforts should focus on promoting sun protection measures to minimize the risk of new lesions and prevent exacerbation of existing ones. Additionally, providing information on available treatment options, including cryotherapy, curettage, and topical therapies, empowers patients to make informed decisions about their care. By fostering awareness and encouraging proactive skin health practices, clinicians contribute to reducing patient anxiety, promoting early detection, and ultimately improving outcomes in individuals with seborrheic keratosis.

Pearls and Other Issues

Understanding seborrheic keratosis is crucial for clinicians to effectively differentiate these benign lesions from potentially malignant skin conditions. By recognizing key diagnostic features and nuances in presentation, clinicians can confidently manage patients with seborrheic keratosis while minimizing unnecessary interventions. Pertinent clinical pearls include the following:

- Human seborrheic keratoses are the most frequent benign skin tumors.

- These benign skin lesions are very common in adults and older individuals.

- Seborrheic keratosis can mimic other malignant skin disorders due to its clinical heterogeneity.

- Dermoscopy may be helpful in the diagnostic process.

- Typically, there is no indication for treating seborrheic keratosis if there is no suspicion of malignancy.

- Seborrheic keratosis removal is primarily for aesthetic reasons or secondary to chronic irritation.

- There are a number of treatment options available, including cryotherapy, excision, and laser ablation.

- Understanding the etiology of seborrheic keratosis has not led to new treatments.

- Recent clinical trials with topical hydrogen peroxide revealed it may be an alternative for facial lesions.

- The sign of Leser-Trelat refers to the sudden appearance of seborrheic keratosis that suggests internal malignancy, such as gastrointestinal or pulmonary carcinomas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of patients with seborrheic keratosis requires a multidisciplinary approach involving physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals in the outpatient setting. Generally, these lesions are benign and have distinguishing features. However, there can be some morphological similarities with malignant skin lesions. Overlapping lesions can make the diagnosis and workup of these lesions more challenging. Patients with large numbers of seborrheic keratoses need screening, as there can be an increased chance of missing coexisting malignant skin lesions. Primary care clinicians should consult with a dermatologist if the diagnosis remains unclear.

A team-oriented approach results in the best outcomes for patients with seborrheic keratosis. Early incorporation of a dermatologist into the patient’s care may aid in the screening and identification of any new or suspicious skin lesions. Dermatologists can integrate the most current treatment modalities, such as laser therapy. Nurses will often have more contact with the patient, can provide counseling, monitor treatment effectiveness following the procedure, and can report to the managing clinician regarding their observations or potential complications from treatment. Pharmacists play a vital role in medication management, counseling on topical treatments, and possible interactions.

By fostering a culture of teamwork and mutual respect, healthcare professionals can enhance patient-centered care, improve outcomes, and elevate team performance in managing patients affected by seborrheic keratosis. Through ongoing education and collaboration, the interprofessional team can optimize patient safety, satisfaction, and overall well-being.