Continuing Education Activity

Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome (GLPLS) is a variant of lichen planopilaris, the follicular form of lichen planus. GLPLS is one of 3 lichen planopilaris variants alongside frontal fibrosing alopecia and classic lichen planopilaris. The condition's etiology remains uncertain, but a T-cell-mediated autoimmune mechanism is believed to be involved.

GLPLS symptoms typically start with hyperkeratotic papules appearing on the trunk and extremities before alopecia develops. GLPLS is characterized by multifocal, patchy, cicatricial alopecia on the scalp, noncicatricial alopecia in the axillae and perineum, and follicular hyperkeratosis on the trunk and extremities.

The diagnosis relies on clinical presentation, histopathological analysis, and exclusion of similar conditions. Treatment focuses on interrupting disease progression, relieving symptoms, and enhancing cosmesis through various modalities, including topical and systemic medications, surgical interventions, and patient support. Evaluation and treatment involve an interprofessional team. Interventions must be tailored to each patient's needs and monitored for efficacy and safety.

This activity for healthcare professionals is designed to enhance the learner’s competence when evaluating and managing GLPLS. Clinicians develop proficiency in recognizing its clinical manifestations, understanding its pathophysiology, and implementing appropriate treatment modalities. Greater competence leads to improved interprofessional collaboration and patient care, enhancing prognosis and quality of life for affected individuals.

Objectives:

Identify the signs and symptoms suggestive of Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome.

Develop a clinically guided diagnostic plan for an individual with suspected Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome.

Implement individualized management strategies for patients with Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome.

Apply effective strategies to improve care coordination among interprofessional team members to facilitate positive outcomes for patients with Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur syndrome.

Introduction

Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur Syndrome Overview

Graham-Little-Piccardi-Lasseur Syndrome (GLPLS) is a rare subtype of lichen planopilaris, first discovered by Piccardi in 1913 and further characterized 2 years later by Ernst Graham Little in a mutual patient with Lasseur. [1] Lichen planopilaris is a follicular variant of lichen planus.

Lichen planopilaris' 3 presentations include GLPLS, frontal fibrosing alopecia, and classic lichen planopilaris.[2] Classic lichen planopilaris is a chronic inflammatory process manifesting as patchy progressive cicatricial scalp alopecia. Frontal fibrosing alopecia presents with band-like cicatricial alopecia on the scalp's frontal and temporal zones.[3][4] GLPLS is characterized by multifocal, patchy, cicatricial alopecia on the scalp, noncicatricial alopecia in the axillae and perineum, and follicular hyperkeratosis on the trunk and extremities.[5][6] GLPLS symptoms may occur in any order, often starting with hyperkeratotic papules on the trunk and extremities before alopecia develops in any location (see Image. Lichen Planopilaris).

GLPLS constitutes a small fraction of lichen planopilaris cases. The condition predominantly affects white women, with onset typically between 30 and 70 years old. Correlations exist with various factors such as hepatitis B vaccination, androgen insensitivity syndrome, HLA DR-1 positivity (in a mother and daughter), vitamin A deficiency, hormonal dysfunction, and neuropsychological issues. Managing GLPLS focuses on immune response reduction to prevent follicular scarring, though reliable therapeutic regimens are still lacking. Research suggests JAK inhibition with tofacitinib may normalize interferon-mediated (IFN-mediated) T-cell chemotaxis, potentially preventing infundibular inflammation. Despite theoretical advancements, healthcare professionals struggle to fully treat patients, emphasizing the need for better preventive measures to mitigate long-term complications.

Hair Histology and the Hair Cycle

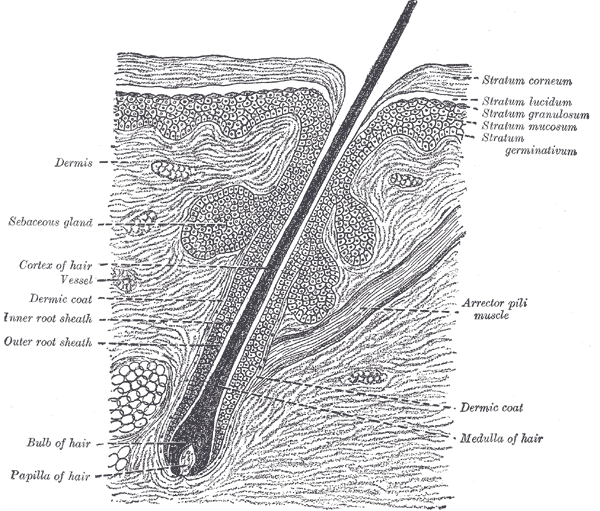

Hair follicles consist of upper (permanent) and lower (transitory) segments. The upper segment comprises the infundibulum, extending from the epidermis to the sebaceous duct, and the isthmus, which houses stem cells at the bulge region. The lower segment is divided into the trunk (stem) and the bulb, with the trunk extending from the arrector pili muscle's insertion to the bulb's cornified part (see Image. The Common Integument, Section of Skin). The bulb becomes completely keratinized beyond this region, known as Adamson’s fringe A, stretching to the hair follicle's base.

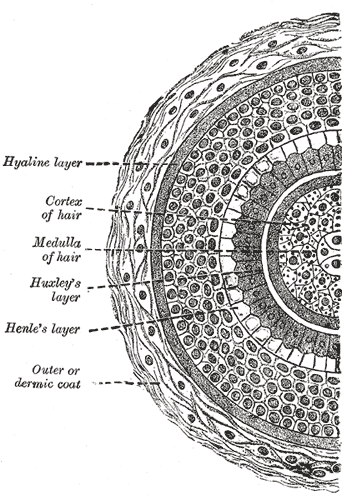

The follicular bulb houses the dermal papilla, providing blood supply and nutrients through a central capillary. The bulb also contains progenitor cells, dendritic melanocytes, and 3 internal hair sheath layers—Henle, Huxley, and cuticle—along with the external root sheath and vitreous membrane (basement membrane). The hair shaft has a cuticle, cortex, and medulla and becomes visible at higher levels of the follicle (see Image. Hair Follicle Transverse Section). The internal hair sheath merges into a single, fully keratinized stratum, while the external root sheath increases in layers. Desquamation occurs in the upper trunk portions of the internal hair sheath, while keratinization happens in the external root sheath. The follicle exhibits keratinization similar to the epidermis at the infundibulum's level, with a distinguishable granular layer and stratum corneum.

Hair can be classified into 3 types: lanugo, vellus, and terminal. Lanugo hair is fine and covers the fetus during development, typically disappearing after birth. Vellus hair is less than 1 cm long and has a diameter of less than 0.03 mm. Vellus hair lacks a medulla, and its bulb is located in the upper dermis. Terminal hair is longer than 1 cm and has a diameter greater than 0.06 mm. This hair type possesses a cortex and a medulla, and its bulb is located in the subcutaneous tissue. Terminal hair may be categorized into androgen-dependent areas (eg, scalp, beard, chest, axillae, and pubic region) and androgen-independent areas (eg, eyebrows and eyelashes). Androgens do not influence vellus hair.

The hair follicle's lower segment is involved in the hair growth cycle. About 85% to 100% of scalp hairs are typically in the anagen phase, which lasts 2 to 7 years. Around 1% of scalp hairs exist in the catagen phase, a period lasting 2 to 3 weeks. Matrix cell apoptosis occurs during this period, thinning the lower segment. The vitreous membrane and lower hair shaft thicken, surrounded solely by the external root sheath and form a “club hair” appearance. Telogen is the resting phase, comprising 0% to 15% of scalp hairs. This stage lasts about 100 days and precedes the initiation of new hair growth and another cycle.[7][8]

Etiology

GLPLS' etiology is an enigma. Most schools of thought attribute GLPLS symptoms to a T-cell-mediated autoimmune process.[9] Mechanisms such as altered integrin expression and IFN-γ dysregulation, present in lichen planopilaris, likely contribute to GLPLS. Inflammation and altered integrin expression may lead to cicatricial alopecia, with affected follicular roots showing positive anagen hair pull tests.[10][11] Rodriguez-Bayona et al. reported strong autoimmune reactivity to a centromere-specific protein, inner centromere protein or "INCENP," suggesting mitotic cellular deficits. Although further investigation is needed on INCENP autoantibody prevalence in GLPLS, this finding marks the first GLPLS-linked antibody.[12] Familial GLPLS across 3 generations has also been reported recently.[13]

Epidemiology

GLPLS mainly affects white women. The average onset age varies from 30 to 70 years old.[14] This lichen planopilaris variant comprises a small portion of the overall cases. A study involving 80 individuals with lichen planopilaris reported only 1 case consistent with GLPLS. The condition correlates with various factors, including hepatitis B vaccination, androgen insensitivity syndrome, HLA DR-1 positivity in a mother and daughter, vitamin A deficiency, hormonal dysfunction, and neuropsychological issues.[15]

Pathophysiology

Pilosebaceous unit damage is crucial in GLPLS pathogenesis. Lesional skin exhibits increased IFN-γ-induced chemokines, recruiting cytotoxic T-cells to the follicular infundibulum.[16] IFN-γ signaling pathway dysregulation increases major histocompatibility complex classes 1 and 2 expression, enhancing antigenic presentation to T-cells. Damage to the chromosomal passenger protein INCENP impedes microtubule binding, causing mislocalization and dysfunction of chromosome passenger complexes. Consequently, chromosomal segregation, central spindle formation, and cytoplasmic allocation are impaired.[17][18] These alterations create metaphase abnormalities that reduce overall mitotic function.

Histopathology

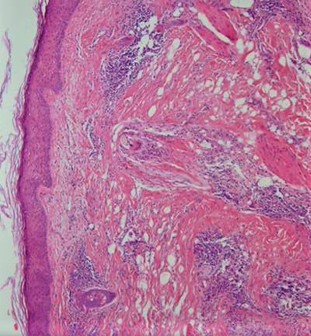

Histopathologic examination of cicatricial alopecia areas in GLPLS reveals a dilated follicular lumen superior to the sebaceous gland with a dense hyperkeratotic plug in the infundibulum's lower portion. Nearby epithelium peripheral to the follicular infundibulum shows hypergranulosis, vacuolar keratinocyte degradation, and a lymphocytic infiltrate obscuring the dermal-epidermal junction, with increased dense collagen bundles at the follicular base. Examination of hyperkeratotic papules on the trunk and extremities shows expanded keratin-filled follicular openings, vacuolar degradation of adjacent keratinocytes, and a lymphohistiocytic infiltrate at the dermal-epidermal junction.[19]

History and Physical

History

A thorough clinical evaluation is key to diagnosing GLPLS. On history, patients with this condition typically present with a unique hair loss pattern characterized by multifocal, patchy alopecia with hair follicle scarring (cicatricial). Patients may also exhibit noncicatricial alopecia in the axillae and perineum. Follicular hyperkeratosis is often reported on the trunk and extremities. Symptoms are gradual in onset, with hyperkeratotic papules often appearing before hair loss. These papules may evolve into hyperkeratotic plaques over time. Information that may help assess for secondary alopecia causes include the amount of hair loss, the presence of psychosocial stress, or endocrinological abnormalities.

Physical Examination

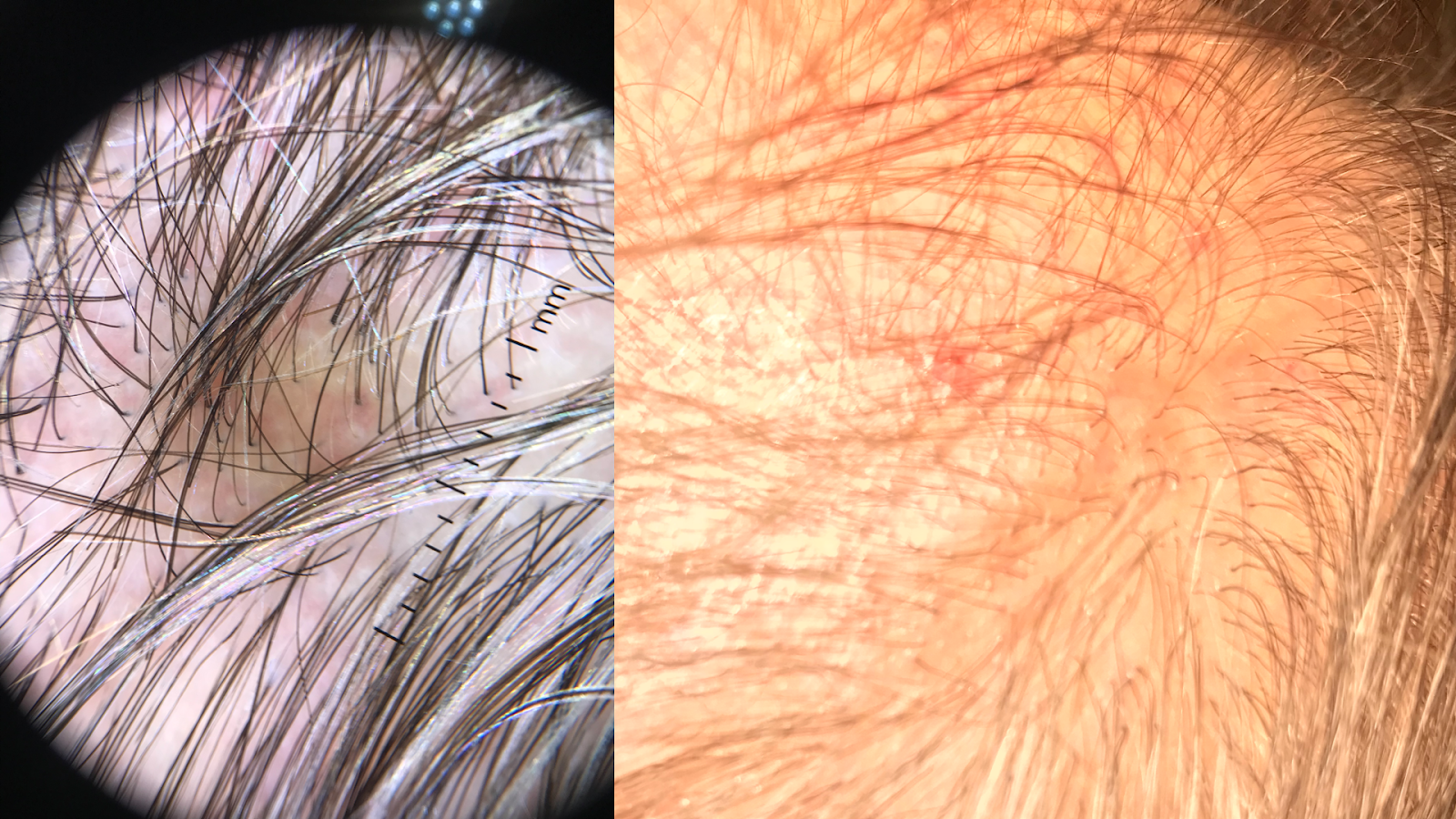

Physical examination should include a full-body skin check, noting the multifocal, patchy cicatricial scalp hair loss and nonscarring perineal and axillary alopecia. The trunk and extremities may have hyperkeratotic papules with surrounding perifollicular erythema, which are key features of GLPLS. An anagen hair pull test is often positive in GLPLS because the hair follicles are weakly anchored in affected individuals. Dermoscopy may show perifollicular erythema and scaling in alopecic areas (see Image. Dermoscopic and Clinical Findings in Lichen Planopilaris).

Evaluation

Skin biopsy and physical examination findings serve as the primary diagnostic methods for GLPLS. Histological analysis of cicatricial areas and hyperkeratotic papules reveals lichen planopilaris features, indicating perifollicular inflammation leading to pilosebaceous destruction (see Image. Lichen Planopilaris Histopathology). Late-stage GLPLS may involve arrector pili muscle corruption. Clinical evaluation typically shows erythematous follicular papules varying in size from 1 to 4 mm, nonscarring alopecia in the perineum and axillae, and patchy cicatricial scalp alopecia. Hyperkeratotic papules are common on the trunk, thighs, inner and outer arms, and wrists, with or without pruritus. Hyperkeratotic papules may precede scalp alopecia onset, but symptom order varies.[20]

Treatment / Management

Managing GLPLS remains elusive due to the lack of a dominant therapeutic regimen. Treatment focuses on mitigating the immunological response before follicular scarring occurs. Novel research suggests that JAK inhibition with tofacitinib normalizes IFN-mediated T-cell chemotaxis, preventing infundibular inflammation. A case series of 8 lichen planopilaris patients reported that a twice-daily 5mg dose of tofacitinib resulted in a 30% to 94% improvement in disease severity.

Zegarska et al described a patient treated with prednisone 30 mg for 2 weeks, followed by a reduction to 20 mg, alongside psoralen and ultraviolet light A at 12 joules. This regimen moderately improved follicular hyperkeratosis on the trunk and extremities.[21] The follicular papules were reduced, but cicatricial scalp alopecia and noncicatricial axillary and perineal hair loss did not diminish.[22]

Other therapies that have also been used to manage GLPLS include intralesional glucocorticoids, topical glucocorticoids, systemic glucocorticoids, cyclosporine, tacrolimus ointment, and systemic retinoids. Most treatment methods reduce perifollicular erythema and inflammation without affecting scalp, perineal, and axillary hair loss. Recent reports have documented successful treatment of GLPLS using narrow-band UVB phototherapy.[23]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of GLPLS includes the following conditions:

- Classical lichen planopilaris

- Pseudopelade of Brocq [24]

- Frontal fibrosing alopecia

- Lichen spinulosus

- Androgen insensitivity syndrome

- Discoid lupus erythematosus [25]

- Secondary syphilis [26]

- Addison disease [27]

These conditions often manifest with skin lesions and scalp conditions resembling GLPLS symptoms. A thorough clinical investigation and appropriate diagnostic testing can guide management strategies.

Prognosis

GLPLS' course is often drawn out but may improve with treatment. Still, full alopecic symptom resolution with current treatment modalities is rare. Data on the average disease duration of GLPLS are limited, though some cases persist for over 20 years. Zegarska et al report durations ranging from 6 months to 10 years.[22] Adequate medical management may significantly improve the prognosis, particularly in reducing hyperkeratotic papules on the trunk and extremities.

Complications

GLPLS can cause considerable psychosocial distress as it can significantly change a person's appearance. However, the condition does not exhibit systemic manifestations. Further research on INCENP's role, especially in overall mitotic function, may uncover associated morbidities, but none have been identified. The GLPLS complication that primarily lasts is follicular scarring from infundibular inflammation, permanently damaging pilosebaceous units, particularly in the scalp.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with GLPLS require comprehensive prognosis and treatment explanations to establish realistic expectations. Many patients opt out of treatment because current therapies often do not address the condition's alopecic aspects. Treatments cannot reverse cicatricial damage, but early intervention may slow noncicatricial alopecia, cicatricial scalp alopecia, and hyperkeratotic papule formation progression. Clarifying therapy goals can enhance compliance and foster stronger patient-physician relationships.

Pearls and Other Issues

GLPLS is a complex clinical entity presenting with multifocal, patchy cicatricial scalp alopecia, noncicatricial alopecia in areas like the axillae and perineum, and hyperkeratotic papules on the trunk and extremities. Diagnosis relies on combining clinical presentation, histopathological findings, and exclusion of similar conditions. Treatment remains challenging, focusing on immunomodulatory agents to mitigate inflammation and disease progression. While therapies may not reverse existing cicatricial damage, early intervention can slow further hair loss and papule formation. Patient education on treatment goals fosters compliance and maintains strong patient-physician relationships.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional approach involving various medical specialties is essential for the comprehensive evaluation and management of GLPLS. Dermatologists, dermatopathologists, pharmacists, hair-loss support groups, and psychologists play crucial roles in diagnosis and long-term care. Besides ensuring accurate diagnosis, trained professionals and alopecia support groups offer vital psychosocial support, fostering a sense of belonging and reducing stress associated with a GLPLS diagnosis.[28]