Introduction

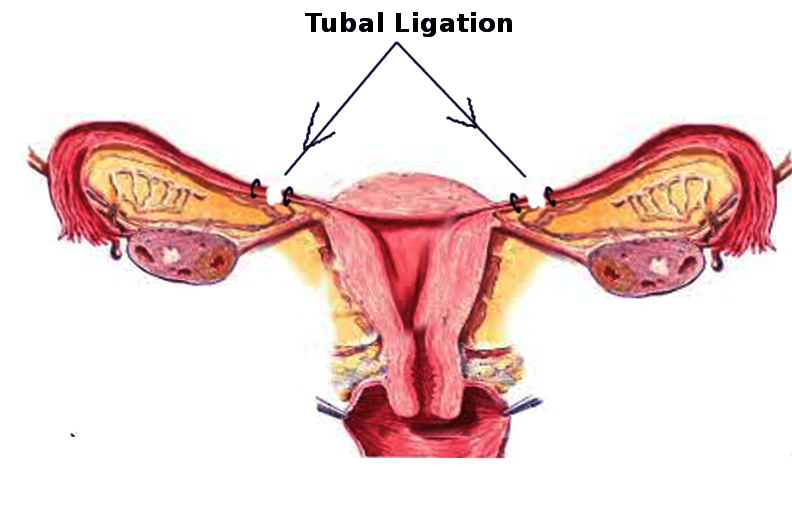

Contraceptive options for individuals and couples range widely, from barrier methods to short- and long-acting reversible contraception to permanent sterilization. Around the world, sterilization is the chosen option for more than 220 million couples desiring contraception.[1] Data from the National Survey of Family Growth show that from 2006 to 2010, sterilization was the most common method of contraception used in the United States, utilized by 47.3% of married couples.[1] Tubal ligation accounted for 30.2% and vasectomy for 17.1%.[1] For those who have completed childbearing, sterilization using tubal ligation is a safe and effective contraceptive option. Additionally, tubal ligation may have non-contraceptive benefits, such as improved menstrual bleeding patterns and decreased risks of ovarian cancer. Most tubal ligations are performed in an ambulatory setting on an outpatient basis unless performed after cesarean section or in the period immediately postpartum. As with any procedure, the patient must understand the risks, benefits, indications, and alternatives.

Anatomy and Physiology

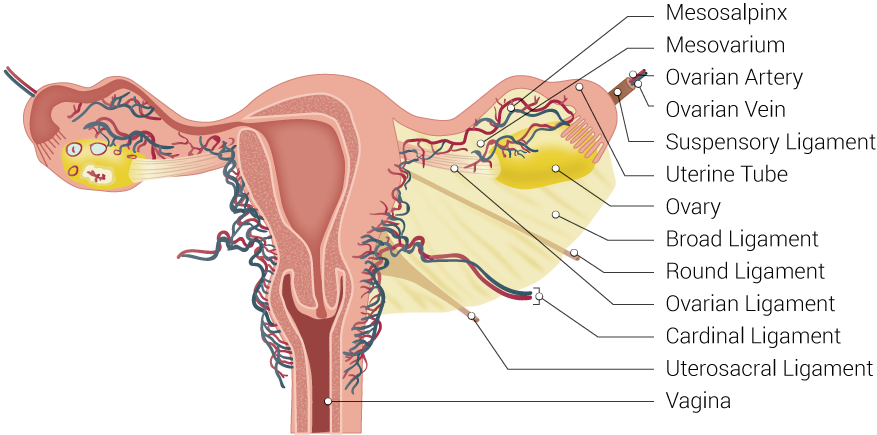

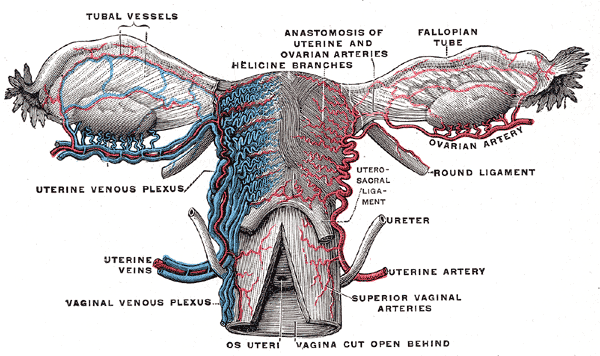

The Fallopian tube, also known by the names uterine tube or oviduct, is named after the Italian anatomist Gabriel Fallopius.[2] It is a J-shaped structure that is an essential component of the female reproductive tract. Each tube is approximately 10 to 12 cm long. The uterine tubes are paired, located at the superior aspect of the uterine cavity bilaterally. Each tube exits the uterus at the uterine cornua and appears between the round and utero-ovarian ligaments at the upper margins of the broad ligament bilaterally. The peritoneum of the broad ligament immediately inferior to the Fallopian tube is called the mesosalpinx.

Embryologically, the Fallopian tubes derive from the coelomic epithelium via the paramesonephric ducts. Between week five and week six after fertilization, Muller’s groove arises on each side laterally to the mesonephric duct. Muller’s groove originates from the coelomic epithelium, and the edges of this groove form the paramesonephric or Mullerian ducts. These paramesonephric ducts, in turn, fuse in the eighth week to form the uterus, Fallopian tubes, cervix, and upper two-thirds of the vagina.[2]

Each tube consists of several anatomic regions [2][3]:

- Ostia - the tubal openings into the uterine cavity, which is visible during hysteroscopy

- Intramural/Interstitial - the most proximal portion of the Fallopian tube which passes through the muscle of the uterus

- Isthmus - narrow part of the Fallopian tube with few mucosal folds (plicae) and a thick muscularis layer

- Ampulla - the highly-folded portion of the Fallopian tube with mucosal folds (plicae) and secondary folds dividing the lumen; the part of the tube where fertilization most commonly occurs

- Infundibulum - the funnel-shaped widest portion of the Fallopian tube, proximal to the fimbriae, which channels the released ovum toward the uterus

- Fimbriae - the finger-like distal end of the Fallopian tube, closest to the ovary, which sweeps the ovum into the Fallopian tube

The wall of the Fallopian tube itself consists of three layers [2][3]:

- Endosalpinx - internal mucosal layer, with ciliated and secretory cells

- Myosalpinx - intermediate smooth muscular layer, with peristaltic activity important for egg and sperm transport

- Serosa - the outer layer, continuous with the peritoneum of the broad ligament, the upper margin of which is the mesosalpinx

The primary function of the Fallopian tube is to transport sperm toward the egg/ovum and then allow the fertilized egg to travel back to the uterus for implantation. Thus, occlusion or removal of the Fallopian tube acts to prevent fertilization and subsequent pregnancy. At least 3 cm of the isthmus of the tube must undergo complete coagulation if electrocoagulation is being utilized to perform a tubal ligation.[1]

Indications

The primary indication for tubal ligation is the desire for permanent sterilization. Those who have completed childbearing and desire a non-reversible contraceptive option are candidates for tubal ligation. Removal of the Fallopian tubes, or salpingectomy, has been advocated as a method for the prevention of ovarian cancer. The surgeon can perform salpingectomy opportunistically as a method of tubal ligation at the time of hysterectomy.[4] Currently, bilateral salpingectomy alone is not the recommendation for risk reduction in patients with a high risk of ovarian cancer, such as BRCA mutation carriers.[5]

Contraindications

The main contraindication to tubal ligation is a patient’s desire for future childbearing. While tubal anastomosis or in-vitro fertilization (IVF) is an option for some patients, success cannot be guaranteed, and cost can be a significant barrier for many. In one review of tubal anastomosis, pooled pregnancy rates for the procedure were 42 to 69% but varied by the method used.[6]

Various methods of tubal ligation carry individual surgical risks. Some patients may not qualify as good surgical candidates for abdominal or laparoscopic surgery (e.g., obesity, adhesive disease, medical comorbidities). Anesthesia carries risk. Some patients, anatomically, may not be candidates for tubal occlusion techniques with clips or rings if their Fallopian tubes are abnormal.

The consent process for tubal ligation must be careful and complete. In counseling patients regarding tubal ligation, it should be made clear that the procedure is permanent and not intended to be reversible. Alternatives, such as long-acting reversible contraceptives or vasectomy, should be discussed. Patients must also understand the details of the procedure itself and any associated risks, as well as the risks and benefits of anesthesia. Counseling should include a discussion regarding the risks of failure and ectopic pregnancy. As tubal ligation does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, patients who are at risk should use barrier methods even after sterilization. Lastly, providers and patients all need to be aware of any local laws or regulations regarding sterilization.[1]

Even if counseling is adequate, there remains a risk of regret after tubal ligation. The CREST study found a cumulative probability of regret of 12.7% over 14 years.[7] Regret can be challenging to quantify, and in some studies, a request for information regarding a reversal procedure has served as a marker of regret.[1] However, clinicians should not automatically deny the procedure to patients who have risk factors for regret.[1]

The following have correlations with an increased risk of regret after sterilization [1][7]:

- Young age (less than 30)

- Non-White race

- Marital status (being unmarried carries higher risk)

- Timing (decreasing regret with increasing interval between delivery and sterilization)

- Adequacy of counseling (less information regarding the procedure or alternatives increases regret)

- The pressure to decide (increased regret if under pressure from spouse/partner or medical indications)

Interestingly, several factors do not have an association with regret or subsequent desire for information on reversal [1][7]:

- Number of living children

- Postabortion sterilization, as compared with interval sterilization

For patients planning postpartum sterilization, patients and providers should consider postponing the procedure if there are intrapartum or postpartum neonatal or maternal complications.[1]

Ethically, tubal ligation in specific populations can be challenging. For example, ensuring adequate informed consent and a lack of coercion in the incarcerated population can be difficult. Between 2006 and 2010, over 140 women in California prisons underwent publicly funded tubal ligations. Despite all of these having signed consent forms, analysis by researchers after the fact showed that many of the women felt significant pressure from both prison and hospital physicians and that many of the procedures were undesired [8]. On the other hand, some incarcerated women may genuinely desire sterilization. Overall, the recommendation is that incarcerated women should only (rarely) undergo sterilization after excellent documentation (preferably pre-incarceration) and access to long-acting reversible methods are made available.[8]

Patients who may be uncertain regarding permanent sterilization but who desire effective contraception should receive counsel regarding other highly-effective contraceptive options. For example, the estimated failure rate of tubal ligation is 0.5 per 100 women in the first year.[9] Comparatively, the levonorgestrel intrauterine device is 0.2 per 100, the copper IUD is 0.8 per 100, and the contraceptive implant is 0.05 per 100 women in the first year.[9] Therefore, the availability of contraceptive options with similar efficacy to tubal ligation, but that are also reversible, is a crucial part of patient informed consent. If a patient is in a relationship with a male partner and the couple desires sterilization, vasectomy is an alternative to tubal ligation, with a failure rate of 0.15 per 100 women in the first year.[9]

Ultimately, the choice to have a tubal ligation is an individual one.

Equipment

The equipment needed for tubal ligation varies based on the technique and approach. To perform a tubal ligation, the surgeon must first visualize the Fallopian tube. Following visualization, the patency between ovary/ovum and uterus must be interrupted.

During a cesarean section, the visualization of the Fallopian tube is often simple after the uterus becomes exteriorized. The surgeon can grasp the tube with a Babcock clamp and the chosen technique utilized. If the uterus is not exteriorized, or if it cannot be, visualization of the tube can be more difficult depending on the amount of adhesive disease present. Various retractors, such as a Richardson retractor, may be utilized to aid in visualizing the tube. The Bovie cautery used during the cesarean can also be used during the tubal ligation.

For a postpartum or postabortion procedure, access to the Fallopian tube is achieved using a mini-laparotomy incision. A scalpel, several small retractors (such as a Senn or Army-Navy retractor), and surgical scissors (such as Metzenbaum or Mayo scissors) will suffice. A suction tip, such as a Yankauer, may also be utilized. A clamp such as a Babcock is again used to grasp the tube once it is in the surgical incision, and the chosen technique for tubal ligation can take place.

Surgeons often perform interval procedures laparoscopically. Therefore, standard laparoscopic equipment is necessary, including the laparoscope, CO2 gas and tubing, light, video equipment, trocars, and graspers. Equipment for the chosen technique of laparoscopic entry is required, per surgeon preference. Once abdominal entry is achieved and the Fallopian tube visualized laparoscopically, the chosen method for tubal ligation can commence.

If utilizing electrocautery, as in some laparoscopic tubal ligations, a bipolar energy source and instrument (Kleppinger) are necessary. Laparoscopic bilateral salpingectomy can also be performed, for example, using a bipolar combination sealing/cutting instrument. Various clips and bands may also help occlude the Fallopian tubes during laparoscopy. Clips or bands are also options during postpartum/postabortion sterilizations or cesarean sections. Open techniques utilizing suture are common. With the increase in salpingectomy, some physicians are choosing to use laparoscopic bipolar sealing/cutting instruments at the time of postpartum or cesarean tubal ligations.

Closure of the skin incision(s) can be achieved using sutures and/or skin glue.

Hysteroscopic sterilization techniques have been described and used, though they are no longer widely utilized in the United States. If the surgeon chooses this technique, then hysteroscopic equipment (hysteroscope, distension medium, light, video equipment, etc.) is needed, along with vaginal instruments (speculum or retractors, tenaculum, dilators, etc.). Whatever method is being utilized to occlude the tubes is also necessary.

Personnel

The interprofessional team includes:

- Surgeon

- Surgical assistant (partner, resident, scrub technician, etc.)

- Scrub technician

- Anesthetist/Anesthesiologist (as indicated for local, regional, or general anesthesia)

- Surgical circulator (usually a nurse)

Preparation

The most critical aspect of preparing for tubal ligation is ensuring adequate patient counseling and informed consent. Appropriate documentation and consent forms should be in place before the procedure. Laws and restrictions regarding timing and the consent process require careful adherence. The technique and approach most appropriate for the individual patient must also be determined, which will allow adequate counseling with regards to any surgical risks, risks of failure, risks of anesthesia, recovery, and follow-up unique to each technique or approach.

The timing of tubal ligation can be [1]:

- Postpartum - at the time of cesarean section or after vaginal delivery before discharge home

- Postabortion - immediately after an uncomplicated spontaneous abortion or induced abortion

- Interval - procedure separate from pregnancy

Appropriate skin preparation preoperatively should be performed. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended prior to laparoscopic tubal ligations. Antibiotics are also not routinely administered before mini-laparotomy. The patient should have an empty stomach appropriate for the surgical approach chosen.

Technique or Treatment

Laparoscopic

This is the most common technique for interval tubal ligations. It allows for inspection of the abdomen and pelvis, is effective immediately, and allows a relatively rapid return to activity.[1] Anesthesia is typically general; however, this can take place with local anesthetic and sedation. Laparoscopic tubal ligation is possible via three methods [1]:

- Electrocoagulation: Bipolar device is used to occlude the tube, at least 3 cm of the isthmic portion. Monopolar electrocoagulation is seldom a choice due to association with thermal bowel injury.

- Mechanical Devices: In the United States, the most commonly used devices are the silicone rubber band, the spring-loaded clip, and the titanium clip lined with silicone rubber. These are deployed using special applicators, and they are most effective if the Fallopian tubes are normal. Misapplication and failure can occur if the tubes are thickened, dilated, or form adhesions.

- Tubal Excision: The surgeon can remove part or all of the Fallopian tubes. This technique is especially useful if the tubes are abnormal, it has high contraceptive efficacy, and it may decrease the risk of ovarian cancer.

Hysteroscopic

In the United States, there are currently no hysteroscopic sterilization devices on the market. Hysteroscopic sterilization cannot be done postpartum or postabortion. It offers a relatively non-invasive method for tubal occlusion that could be beneficial to patients who are weak surgical candidates, and it has the benefit of being able to be performed in the office setting. The hysteroscopic technique involves introducing medicine into the Fallopian tubes via the tubal ostia, which subsequently block or scar the tubes. Some past hysteroscopic techniques required follow-up imaging to ensure occlusion. Either sedation or general anesthesia are options if this procedure occurs in the operating room. In the office setting, a paracervical block or light sedation are options if safely available.

Laparotomy/Minilaparotomy

This technique is generally used for postpartum procedures, though it may merit consideration for patients for whom laparoscopy carries such a high risk that laparotomy is safer.[1] It is also suitable for low-resource settings, because it utilizes basic (and usually reusable) equipment, unlike laparoscopy.[1] A 2 to 3 cm incision is made relative to the fundus (infra-umbilical postpartum or suprapubic postabortion/interval), though a larger incision may be necessary for obese patients.[1] During a cesarean postpartum tubal ligation, the abdomen is already open. The patient's existing regional anesthetic is sufficient for procedures done during a cesarean. After a vaginal delivery, the patient's epidural catheter may remain in place, or a spinal anesthetic can be placed if the patient did not have an epidural or if the epidural catheter required removal.

- Pomeroy: Mid-isthmic portion of the Fallopian tube is elevated and then folded at the midpoint. One or two rapidly absorbable sutures are tied around the double thickness of the tube, and the folded portion excised sharply.

- Parkland: An opening is made in an avascular section of the mesosalpinx. Two absorbable suture ties are passed through the opening and used to ligate the proximal and distal ends of the Fallopian tube. The segment (at least 2 cm) between the ties gets excised.

- Uchida: The midportion of the Fallopian tube is ligated and excised. Then the utero-tubal serosa is hydrodissected, and the proximal tubal stump gets pulled into the mesosalpinx. The peritoneum is closed over the proximal cut end of the tube.

- Irving: The midportion of the Fallopian tube is ligated and excised. Then the proximal tubal stump is inserted into an incision made into the myometrium and securely sutured to bury the proximal stump in the myometrium.

- Distal Fimbriectomy: The fimbriated end of the Fallopian tube is ligated and excised.

- Complete Salpingectomy: The entire Fallopian tube to the (except the interstitial portion) is excised; this can be done with suture ligation, laparoscopic bipolar devices, etc.

Tubal segments require a pathology consultation to confirm transection. A common structure ligated accidentally is the round ligament. Identification of the fimbriated end of the Fallopian tube before excision can help confirm the correct structure. Unless performing a complete salpingectomy, care is necessary to excise a sufficient section of the Fallopian tube. All cut edges require inspection for hemostasis.

Complications

Laparoscopic tubal ligation is overall safe and effective. Mortality rates in the United States are estimated at 1 to 2 per 100000 procedures, with most deaths attributable to hypoventilation and cardiopulmonary arrest while administering general anesthesia.[1] Several studies have shown no deaths at all.[1] Major laparoscopic complications include unplanned major surgery, transfusion, damage to surrounding structures, fever, infection, bleeding, transfusion, and readmission. These reports show approximately 0.9 to 1.6 per 100 procedures.[1] The reported risk of conversion to open laparotomy is 0.9 per 100 cases.[1] The risks of complications increase with the use of general anesthesia, previous pelvic or abdominal surgery, obesity, and diabetes.[1]

Complications following mini-laparotomy are also very low. In one Swiss study, the overall rate of major morbidity after postpartum tubal ligation was 0.39%.[10] This statistic included cases of blood loss greater than 500cc, febrile morbidity, pulmonary embolism, and stomach injury.[10] The rate of minor morbidity was 0.8%, including urinary tract infections, wound dehiscence, abdominal wall hematomas, uterine injury, and ileus.[10]

The 10-year risk of failure varies by technique [1][11]:

- Postpartum partial salpingectomy = 7.5 per 1000 procedures

- Bipolar coagulation = 24.8 per 1,000 procedures (19.5 per 1000 1978 to 1982 and 6.3 per 1000 1985 to 1987)

- Silicone band = 17.7 per 1000 procedures

- Spring clip = 36.5 per 1000 procedures

Since the original CREST study was published, additional data regarding method efficacy have emerged, and follow-up analyses have taken place on the CREST data. Bipolar coagulation has specifically received attention. During the follow-up period, as techniques evolved, the failure rates fell significantly.[12]

Care should be taken to identify luteal phase pregnancies before performing interval tubal ligations. A pregnancy test is necessary, but also a careful history should be taken to identify patients at risk of being pregnant despite a negative pregnancy test. On average, women ovulate on day 14 of their cycle, where day 1 of the cycle is day 1 of the last menstrual period. The fertile period extends from several days before ovulation to shortly after, and many urine pregnancy tests do not have the sensitivity to detect very early pregnancy. Patients who have had unprotected intercourse within the last week could be at risk of luteal phase pregnancy. Patients at risk should be counseled preoperatively regarding the risks of surgery and anesthesia during early pregnancy, and the risks merit strong consideration against the benefits of proceeding with the procedure.

If pregnancy does occur after tubal ligation, there is a risk of ectopic pregnancy that varies by technique as well [1][11]:

- Postpartum partial salpingectomy = 1.5 per 1000 procedures

- Bipolar coagulation = 17.1 per 1000 procedures

- Silicone band = 7.3 per 1000 procedures

- Spring clip = 8.5 per 1000 procedures

Post-tubal ligation syndrome is a potential complication that is well-documented in the lay media. Its actual existence, however, controversial. Symptoms may include dyspareunia, low back pain, premenstrual tension syndrome, menstrual abnormalities (missed periods, heavy menstrual bleeding), or menopausal symptoms.[13] The etiology of post-tubal ligation syndrome may be related to adnexal vascular disruption.[13] Treatment may be symptomatic if patient bother is mild. However, some patients may require/request surgical management, such as reversal of the tubal ligation.[13]

Clinical Significance

Female sterilization is the most common method of contraception used worldwide. It can be done immediately after delivery or between pregnancies, and the number of techniques available is many. It is crucial to understand the complexities surrounding tubal ligation, including the various surgical risks/benefits/alternatives, alternative contraceptive options, and the challenging ethics involved. An adequate understanding of all these is necessary to counsel patients adequately and obtain valid informed consent.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Approximately half of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended. Tubal ligation offers patients a safe and effective contraceptive option that has a low failure rate, has no risk of user-related failure, and does not require replacement. Barriers do exist concerning access to postpartum sterilization. Unfortunately, only 50% of patients who request postpartum tubal ligation ultimately undergo the procedure. A patient must be 21 years old to be eligible for Medicaid coverage of a sterilization procedure, and consent documents must be signed at least 30 days before the procedure. Operating rooms or anesthesia may not be available, or the institution may be religiously affiliated. Physicians, nurses, anesthesiologists, office staff, and other patient advocates can work together to ensure proper patient education and access to services such as postpartum tubal ligation. Hospital systems and medical providers can develop policies and procedures to ensure consent forms are obtained in the antenatal period and are available at the time of delivery. Providers, including nurses, can emphasize that postpartum tubal ligations are urgent and advocate for these procedures to be scheduled and done. Women receiving care at religiously-affiliated institutions should still be counseled regarding all their options and be offered referrals to other institutions if they desire.[14] [Level V]

Ethically, providers who counsel patients regarding tubal ligation or who participate in these patients’ care may be better able to ensure patient satisfaction and outcomes if they also understand the CREST study and potential pitfalls such as regret and failure. [Level II]

One study looking at written informed consent for tubal ligation found wide variations in the complications discussed, both among providers with the same level of training and between levels of training. This data leaves providers at risk legally. The authors concluded by recommending standardized patient education that can aid in obtaining consistently valid informed consent. This standardized education could be helpful for all members of each patient's healthcare team.[15] [Level V]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

- Ensure the patient understands the procedure

- Educates the patient on the procedure and that it is a permanent form of sterilization

- Ensures a valid consent has been obtained

- Preps the patient

- Prepares the instrument tray for sterilization

- May assist the surgeon

- Labels the specimen for the pathologist

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

- Monitors the patient during surgery

- Monitors the patient after surgery

- Ensures instrument and sponge counts are correct

- Ensure wound hemostasis after surgery