Continuing Education Activity

Familial adenomatous polyposis is an autosomal dominant polyposis syndrome characterized by mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Patients with familial adenomatous polyposis develop hundreds to thousands of polyps throughout the colon and rectum, significantly elevating their lifetime risk of colorectal cancer if left untreated. Moreover, individuals with this condition commonly develop gastric and duodenal polyps, heightening their susceptibility to gastric and duodenal cancers, desmoid fibromatosis, hepatoblastoma, and thyroid cancer. Colectomy is a primary intervention offering substantial risk reduction for colorectal cancer development, emphasizing the importance of timely screening for associated cancers to enable early detection and intervention.

This activity provides healthcare professionals with the knowledge and skills necessary to identify the signs and symptoms of familial adenomatous polyposis, implement appropriate screening techniques, evaluate management options, and establish surveillance protocols for individuals with this condition. By highlighting the pivotal role of the interprofessional care team, this activity underscores the collaborative approach required to effectively care for patients with this complex condition. Participants gain insights into the comprehensive management of familial adenomatous polyposis, ensuring optimal patient outcomes through coordinated and multidisciplinary care delivery.

Objectives:

Identify clinical manifestations and family history suggestive of familial adenomatous polyposis in patients presenting with colorectal polyps or a family history of colorectal cancer.

Implement appropriate screening and surveillance for familial adenomatous polyposis in individuals with suspected or confirmed genetic predisposition.

Apply standardized protocols and decision-making algorithms for managing familial adenomatous polyposis.

Collaborate with interdisciplinary healthcare team members to coordinate comprehensive care and support for patients with familial adenomatous polyposis.

Introduction

Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant polyposis syndrome characterized by varying degrees of penetrance.[1] The primary genetic defect associated with this disorder is a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene. FAP presents with diverse phenotypic expressions, including Gardner and Turcot syndromes.

If left untreated, affected individuals develop hundreds to thousands of polyps throughout the colon and rectum, often manifesting in the early teenage years. This condition ultimately results in an almost 100% lifetime risk of colorectal cancer, typically occurring by age 40. Colectomy is recommended to significantly reduce the risk of developing colorectal cancer. Individuals with FAP face an elevated risk of other malignancies, such as gastric and duodenal adenocarcinoma, hepatoblastoma, and desmoid tumors.[2] Screening for upper gastrointestinal and extraintestinal disease is crucial in managing affected individuals.

Etiology

FAP results from mutations in the APC gene, a tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 5, exhibiting autosomal dominant inheritance. Germline mutations, often involving nonsense mutations, typically lead to classic FAP. The extensive size of the APC gene results in variable genotypes and phenotypes.[3] The location of the gene mutation is crucial in influencing phenotypic variations, including the development of extracolonic manifestations.[4]

Attenuated FAP, a milder form of the disease, arises from APC gene mutations occurring at distinct codons. This condition typically presents with fewer polyps, a later onset age, and a slower progression to cancer.[5] FAP variants such as Gardner syndrome, characterized by colonic polyposis, osteomas, and soft tissue malignancies, and Turcot syndrome, which entails colonic polyposis and central nervous system (CNS) tumors, often exhibit extracolonic features. Genetic testing is recommended if colonoscopy reveals over 20 adenomatous polyps or if FAP-associated cancers are detected in a patient. Although 10% to 30% of patients diagnosed with FAP lack a detectable APC gene mutation, family members should undergo the same surveillance as those with a detectable mutation.[2]

Epidemiology

FAP ranks as the second most common inherited polyposis syndrome.[2] With an estimated incidence ranging between 1 in 5000 and 1 in 18,000 and affecting men and women equally, FAP accounts for approximately 1% of colorectal cancer cases. Approximately 20% to 30% of individuals diagnosed with FAP lack a documented family history and instead display de novo APC mutations.[6] The incidence rates of attenuated FAP and other FAP variants remain unknown.

Pathophysiology

The APC gene acts as a tumor suppressor gene, essential for chromosome alignment during metaphase.[7] The APC protein promotes apoptosis in colonic epithelial cells. Mutations in the APC protein disrupt apoptosis and facilitate uncontrolled cell growth, leading to adenoma development.[7] The adenoma to carcinoma sequence is well documented, progressing sequentially, with APC inactivation as the initial step. Subsequent mutations in other oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, such as KRAS and p53, induce dysplasia and eventual carcinoma.[8] APC gene mutations are prevalent not only in familial cases but also in the majority of sporadic colorectal cancers.[9]

History and Physical

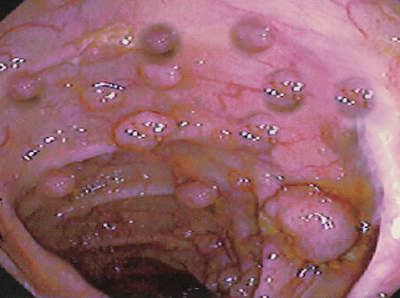

The clinical presentation of FAP varies based on family history and may include colonic and extracolonic symptoms. Individuals without a family history often present with colorectal cancer at a young age or during screening colonoscopy (see Image. Polyposis and Colon Cancer).

Colonic Manifestations

The majority of patients typically present with nonspecific symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal discomfort, and rectal bleeding. Increasingly, patients are identified through screening colonoscopy. Colonoscopic examinations reveal numerous colonic polyps, often exceeding 100, although the number may be lower when screenings start in childhood and are distributed throughout the colon. Attenuated FAP typically involves a reduced number of polyps emerging later in life, predominantly impacting the right colon. This variant normally features approximately 30 polyps and manifests at an average age of over 50 years. Symptoms and signs are related to the degree of polyposis and cancer stage.[10]

Extracolonic Manifestations

Congenital hypertrophy of the retinal epithelium, specific to FAP, typically presents asymptomatically. An eye examination by an ophthalmologist may reveal flat, localized, pigmented retinal lesions. Patients with Gardner syndrome may exhibit osteomas of the mandible or skull. Dental abnormalities, such as impacted teeth, supernumerary teeth, odontomas, and cysts, have been associated with FAP and may be identified on x-rays.

Desmoid tumors are solid connective tissue tumors, often benign but capable of significant growth and local invasion. While uncommon in the general population, they affect 10% to 15% of patients with FAP, with an increased incidence within the abdominal cavity. Individuals with a family history of desmoid tumors face a 25% risk of developing them. Women are twice as likely to develop desmoid tumors compared to men. Notably, surgical trauma is associated with an increased incidence of these tumors. Therefore, colectomy in young patients with FAP is deferred for as long as possible.[11]

Desmoid tumors often present as a large, firm, painless mass. According to the National Cancer Comprehensive Network guidelines, individuals with a significant family history of FAP and desmoid tumors should undergo annual abdominal palpation, with imaging considered.[12] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is beneficial for assessing the relationship to surrounding structures and evidence of local invasion. Typically, these masses appear oval or round with irregular margins. Medical treatment options include anti-estrogens, prostaglandin inhibitors, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, while local therapies include cryotherapy and radiation. Definitive treatment usually entails excision with negative margins.[11]

Gastric polyps are present in approximately 90% of patients with FAP, with the majority being fundic gland polyps that typically do not develop into cancer. However, nonfundic gland polyps are more likely to progress into cancer and should be managed endoscopically. If high-grade dysplasia is detected in any gastric polyp, endoscopic or surgical resection is recommended.[2] According to National Cancer Comprehensive Network guidelines, screening with upper endoscopy should commence at 20 to 25 years.[12] Whenever feasible, patients should undergo endoscopic treatment to address these polyps, but those with high-grade dysplasia or malignant degeneration necessitate surgical resection.[13]

Periampullary and duodenal cancers arise amidst duodenal polyps and rank as the leading cause of death in FAP following colon cancer.[14] The lifetime risk of duodenal cancer is approximately 5% by age 60, with a median onset age of 52. Primarily, the 2nd and 3rd portions of the duodenum are affected—classification systems such as the Spigelman classification aid in risk stratification and determining surveillance frequency. Typically, surveillance begins at age 20 to 25 and is repeated every 2 to 3 years thereafter. Polyps exhibiting dysplasia should undergo endoscopic resection. For polyps considered endoscopically unresectable and those containing invasive cancer, surgical management is recommended.[13]

The increased incidence of hepatoblastoma in patients with FAP is relatively uncommon, predominantly impacting male children younger than 5 years.[15] Currently, there are no universally endorsed screening recommendations. However, screening for high-risk children typically entails liver ultrasound and monitoring alpha-fetoprotein levels every 3 to 6 months.[2]

Thyroid cancer impacts about 2% of patients with FAP, with papillary carcinoma being the most common type. An elevated incidence has been noted within the Hispanic population. There is a documented higher occurrence among women; nearly 90% of thyroid cancers are diagnosed in women with FAP.[2] Guidelines recommend annual thyroid examinations starting in the teenage years, with consideration for annual ultrasound screening in certain patients.

Evaluation

According to National Cancer Comprehensive Network guidelines, patients who test positive for an APC gene mutation should undergo annual sigmoidoscopy (see Image. Familial Adenomatous Polyposis) or colonoscopy from age 10 to 15. Screening for extracolonic manifestations of FAP is essential and includes the following measures:

- Upper endoscopy to examine the stomach and duodenum at 20 to 25 years. Screening may start earlier if a patient undergoes colectomy before this age. The endoscopy should adequately visualize the ampulla of Vater.[12]

- Annual abdominal palpation to assess for desmoid tumors. In patients who have undergone colectomy and have a family history of desmoid tumors, abdominal imaging with a computed tomography (CT) or MRI scan may be used after colectomy.

- Annual thyroid examinations and ultrasounds are conducted starting in the late teenage years for thyroid cancer screening.

- Insufficient data exist to recommend surveillance for CNS tumors, hepatoblastoma, and pancreatic cancers.[16]

Treatment / Management

The management of FAP varies depending on the presence and severity of both colonic and extracolonic manifestations of the disease. Individual patient factors such as age, overall health, and personal preferences may also influence the management approach.

Colonic Disease

Definitive surgical management of FAP involves removing the colon and rectal tissue at risk for polyposis. Various options for resection and reconstruction are available to achieve this:

- Total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis or end ileostomy is the primary surgical approach, providing the highest likelihood of eliminating susceptible colonic mucosa. This procedure involves removing the entire colon and rectum. However, an end ileostomy, the most straightforward reconstruction method, results in a lifetime of living with an ileostomy, which can be challenging for younger individuals. An alternative option for reconstruction is restorative proctocolectomy, where an ileoanal anastomosis is performed with a J-pouch. While this provides anatomic reconstruction, it may raise quality-of-life concerns, particularly regarding fecal continence and sexual and reproductive function.[17]

- Total abdominal colectomy with an ileorectal anastomosis is a less extensive procedure that preserves the rectum. Rectal preservation can improve continence and sexual function. However, patients who undergo this procedure still have a higher risk of the rectal mucosa developing adenocarcinoma, necessitating regular endoscopic surveillance. Approximately one-third of these patients will develop rectal adenocarcinoma and require completion proctectomy.

The choice of surgical procedure depends on several factors, including the extent of the polyp burden, family history of the disease, and patient preferences. Proctocolectomy is recommended for patients with a high rectal polyp burden, while those with minimal polyp burden might choose total abdominal colectomy. Lifestyle considerations such as continence and sexual function significantly influence decision-making, especially among younger patients.[18]

For individuals with attenuated FAP, less extensive surgical procedures may be appropriate based on the polyp burden and distribution. Patients who undergo total proctocolectomy require close monitoring of both the rectal sleeve and ileal pouch, with annual endoscopy. Those with a retained rectum are advised to undergo an endoscopic evaluation every 3 to 6 months.

Exploration of nonsurgical treatment options aimed at delaying surgical resection has yielded limited success. Sulindac, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, has shown promise in small studies by reducing the number of adenomas by nearly 50% and decreasing their size by 65%. However, adenoma recurrence occurred upon discontinuation of sulindac.[2] For patients with a retained rectum, sulindac is a therapeutic option for reducing polyp burden within the rectum. Celecoxib, a selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors inhibitor, has also been studied, with high doses demonstrating a 30% reduction in adenoma burden.[4]

Extracolonic Disease

Upper gastrointestinal polyps pose a significant risk of morbidity and mortality and are the leading cause of death in patients who have undergone colectomy. Screening endoscopy is crucial for identifying gastric, duodenal, and small bowel polyps. Gastric polyps are monitored without intervention, as they rarely progress to malignancy, while endoscopic resection is reserved for larger polyps. Duodenal polyps require close surveillance, and endoscopic resection is necessary for larger polyps. Polypectomy, duodenectomy, or pancreaticoduodenectomy may be warranted in cases of dysplasia or invasive cancer. The Spigelman stage aids in determining the appropriate follow-up regimen.[19]

Desmoid tumors occur at a significantly higher frequency in patients with FAP, particularly in those with a family history of desmoid tumors. Once diagnosed, careful surveillance is essential. Since surgical trauma is a significant risk factor for developing desmoid tumors, it is advisable to delay surgical intervention for as long as feasible. Mesenteric desmoid tumors have the potential to expand and encroach upon the root of the mesenteric vessels. Resecting these tumors is imperative as once the vessels become involved, resection would likely result in a loss of a significant portion of the small bowel. Medical adjuncts such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors can assist in reducing the tumor size preoperatively and as adjuvant treatment afterward.[20]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for FAP include the following:

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colon syndrome

- MUTYH-associated polyposis

- Hyperplastic polyposis

- Inflammatory polyposis

- Juvenile polyposis syndrome

- Lymphomatous polyposis

- Neurofibromatosis type 1

Prognosis

If left untreated, FAP progresses to colorectal cancer in nearly 100% of cases, leading to a shortened life expectancy, with most patients dying by their fourth decade of life.[21] However, survival rates are significantly improved with enhanced screening, surveillance, and prophylactic colectomy. Continued screening for extracolonic cancers is crucial, as duodenal cancer is the most common cause of death in patients who have undergone colonoscopy. Additionally, providing social and psychological support for patients is paramount, given that many individuals are diagnosed early and face significant emotional burdens.[22] It is essential to establish a multidisciplinary team to assist individuals in effectively managing their condition.

Complications

Complications associated with FAP include the following:

- 100% of patients develop colorectal cancer

- Approximately 10% develop duodenal or ampulla of Vater adenocarcinoma

- Up to 20% of patients develop desmoid tumors

- Additional malignancies include hepatoblastoma, medulloblastoma, thyroid cancers [23]

Deterrence and Patient Education

FAP is a genetic condition characterized by colonic polyposis, predisposing individuals to colon cancer and extracolonic manifestations. Early diagnosis through screening is crucial, especially for those with a family history of early colon cancer or colonic polyposis. While medical treatments aid in stabilizing the disease, the primary treatment for FAP remains colectomy with or without proctectomy. Additionally, extracolonic manifestations require thorough screening and close clinical monitoring. With surveillance and surgical intervention, patients with FAP can significantly decrease their risk of colorectal cancer and associated malignancies. Genetic testing for all family members is strongly recommended. Patients often require lifelong surveillance and comprehensive emotional and social support to optimize outcomes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key factors to keep in mind about FAP include the following:

- FAP is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern.

- FAP is primarily caused by germline mutations in the APC gene, located on chromosome 5q21-22.

- FAP is characterized by the development of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps in the colon and rectum, usually starting in adolescence. These polyps can lead to colorectal cancer if not treated.

- FAP can also present with extracolonic manifestations, such as gastric and duodenal adenocarcinoma, desmoid tumors, hepatoblastoma, and papillary thyroid carcinoma.

- The primary management of FAP involves regular screening and surveillance for polyps, followed by prophylactic colectomy with or without proctectomy to prevent colorectal cancer. Additionally, monitoring for extracolonic manifestations and genetic counseling for family members are crucial management components.

- If left untreated, FAP almost invariably progresses to colorectal cancer.

- Genetic testing for APC gene mutations is essential to confirm the diagnosis in suspected cases and identify at-risk family members.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Collaborative management of FAP cases is essential to facilitate comprehensive screening and effective management of this complex condition. The interdisciplinary team should comprise a primary care provider, gastroenterologist, surgeon, otolaryngologist, and geneticist. Additionally, given the early diagnosis often associated with FAP, social, emotional, and psychiatric support may also be integral components of the care team.

Effective communication among team members is paramount for coordinating surveillance, follow-up appointments, and surgical interventions. Since patients with FAP require lifelong monitoring, all team members need to remain actively involved and well-versed in the latest advancements and treatments to ensure optimal patient outcomes.