[1]

Gottesfeld P, Tirima S, Anka SM, Fotso A, Nota MM. Reducing Lead and Silica Dust Exposures in Small-Scale Mining in Northern Nigeria. Annals of work exposures and health. 2019 Jan 7:63(1):1-8. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxy095. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 30535234]

[2]

Skowroński M, Halicka A, Barinow-Wojewódzki A. Pulmonary tuberculosis in a male with silicosis. Advances in respiratory medicine. 2018:86(3):. doi: 10.5603/ARM.2018.0019. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29960278]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[3]

Hoy R, Yates DH. Artificial stone-associated silicosis in Belgium: response. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2019 Feb:76(2):134. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2018-105563. Epub 2018 Dec 11

[PubMed PMID: 30538143]

[4]

Peruzzi C, Nascimento S, Gauer B, Nardi J, Sauer E, Göethel G, Cestonaro L, Fão N, Cattani S, Paim C, Souza J, Gnoatto D, Garcia SC. Inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers at protein and molecular levels in workers occupationally exposed to crystalline silica. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2019 Jan:26(2):1394-1405. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3693-4. Epub 2018 Nov 13

[PubMed PMID: 30426371]

[5]

Wang XX, Zhang HD, Wang XM. [The analysis of the epidemiological characteristics of pneumoconiosis notified in Chongqing from 2011 to 2015]. Zhonghua lao dong wei sheng zhi ye bing za zhi = Zhonghua laodong weisheng zhiyebing zazhi = Chinese journal of industrial hygiene and occupational diseases. 2018 Mar 20:36(3):194-197. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-9391.2018.03.008. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29996220]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence

[6]

Joubert KD, Awori Hayanga J, Strollo DC, Lendermon EA, Yousem SA, Luketich JD, Ensor CR, Shigemura N. Outcomes after lung transplantation for patients with occupational lung diseases. Clinical transplantation. 2019 Jan:33(1):e13460. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13460. Epub 2018 Dec 30

[PubMed PMID: 30506808]

[7]

Li J, Yao W, Hou JY, Zhang L, Bao L, Chen HT, Wang D, Yue ZZ, Li YP, Zhang M, Yu XH, Zhang JH, Qu YQ, Hao CF. The Role of Fibrocyte in the Pathogenesis of Silicosis. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 2018 Apr:31(4):311-316. doi: 10.3967/bes2018.040. Epub

[PubMed PMID: 29773095]

[8]

Guarnieri G,Bizzotto R,Gottardo O,Velo E,Cassaro M,Vio S,Putzu MG,Rossi F,Zuliani P,Liviero F,Mason P,Maestrelli P, Multiorgan accelerated silicosis misdiagnosed as sarcoidosis in two workers exposed to quartz conglomerate dust. Occupational and environmental medicine. 2019 Mar

[PubMed PMID: 30514749]

[9]

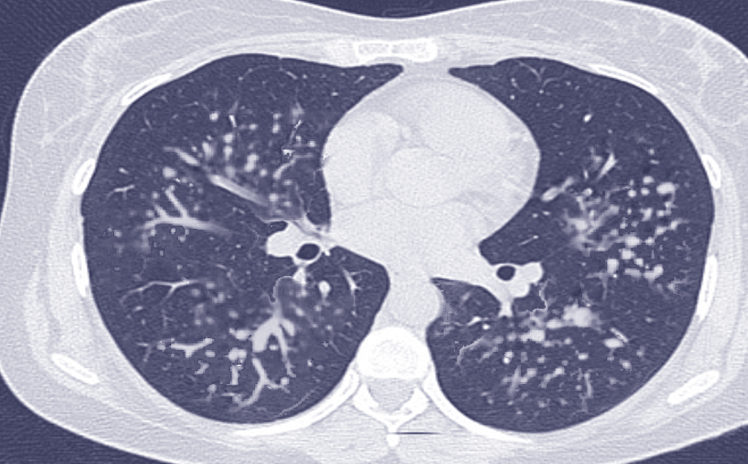

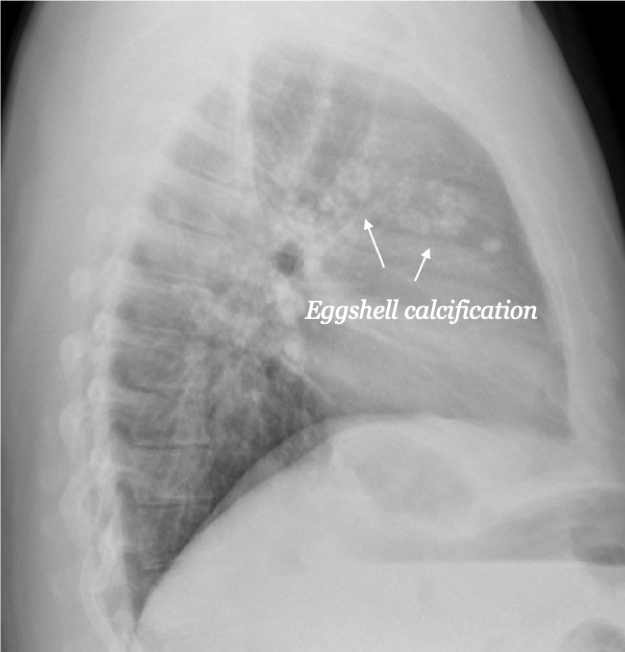

Takahashi M, Nitta N, Kishimoto T, Ohtsuka Y, Honda S, Ashizawa K. Computed tomography findings of arc-welders' pneumoconiosis: Comparison with silicosis. European journal of radiology. 2018 Oct:107():98-104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.08.020. Epub 2018 Aug 24

[PubMed PMID: 30292280]

[10]

Zhang H,Li L,Xiao H,Sun XW,Wang Z,Zhang CL, Silicotuberculosis with oesophagobronchial fistulas and broncholithiasis: a case report. The Journal of international medical research. 2018 Feb

[PubMed PMID: 28703631]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence

[11]

Yang J,Xue J,Hu W,Zhang L,Xu R,Wu S,Wang J,Ma J,Wei J,Wang Y,Wang S,Liu X, Human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome reverts silica-induced airway epithelial cell injury by regulating Bmi1 signaling. Environmental toxicology. 2023 Sep;

[PubMed PMID: 37227716]

[12]

Zhang Y,Liu F,Jia Q,Zheng L,Tang Q,Sai L,Zhang W,Du Z,Peng C,Bo C,Zhang F, Baicalin alleviates silica-induced lung inflammation and fibrosis by inhibiting TLR4/NF-?B pathway in rats. Physiological research. 2023 Apr 30;

[PubMed PMID: 37159856]

[13]

Wang Y,Cheng D,Li Z,Sun W,Zhou S,Peng L,Xiong H,Jia X,Li W,Han L,Liu Y,Ni C, IL33-mediated NPM1 promotes fibroblast-to-myofibroblast transition via ERK/AP-1 signaling in silica-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2023 Aug 29;

[PubMed PMID: 37399107]