Introduction

Aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) is a variant of peripheral artery disease affecting the infrarenal aorta and iliac arteries. Similar to other arterial diseases, aortoiliac occlusive disease obstructs blood flow to distal organs through narrowed lumens or by embolization of plaques. The presentation of AOID can range from asymptomatic to limb-threatening emergencies. Obstructive lesions are usually present in the infrarenal aorta, common iliac artery, internal iliac (hypogastric) artery, external iliac artery, or combinations of any of these vessels. Many risk factors exist for the development of the AIOD, and recognition of these factors enables providers to prescribe medical treatment that may relieve symptoms as well as prolong life. With the discovery of prosthetic graft materials for aortic replacement, surgical treatment of AIOD became available to patients in the 1960s.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) is a variation of peripheral artery disease, specifically affecting the lower aorta. In the same manner as peripheral artery disease, AIOD is typically caused by atherosclerosis. Inciting factors for atherosclerosis and AIOD include diabetes mellitus, elevated homocysteine levels, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and tobacco usage.[1] Risk factors also include age, family history, race, and sex. Another rare but significant etiology is large vessel vasculitis, specifically Takayasu arteritis.[2][3]

Epidemiology

The exact prevalence of aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD), and peripheral artery disease, in general, is difficult to determine since many patients are asymptomatic. Estimates have ranged from 3.56% to greater than 14% for the general population.[4][5] Multiple studies support an increased prevalence in older populations, estimating 14%-20% over 70 years old and 23% over 80 years old.[6][7] A higher preponderance exists in male and non-Hispanic black populations, as well as those affected by the above-mentioned risk factors.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

Underlying etiology risk factors expose endothelial cells to injury through various mechanisms. Endothelial injury and dysfunction contribute to atherosclerosis and its complications by the following:[10]

- Enhanced expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules

- Increased inflammatory cytokines

- Reduced production of nitric oxide

- Increased superoxide anion formation

- Hindrance of cell function from increased serum free fatty acids and insulin

- Increased production of endothelial vasoconstrictors

- Vascular smooth muscle dysfunction and loss of integrity

- Increased expression of prothrombotic factors

History and Physical

Patients are commonly seen with complaints of cramping pain, occurring during and after exercise and relieved by rest. This condition is known as claudication. A detailed history and physical examination are vital to determine the severity of the disease and distinguish it from other diagnoses. Typically, more proximal muscle cramping is related to a higher degree of stenosis. In a particular subset, patients present with a triad of buttock claudication, erectile dysfunction, and absent femoral pulses in a grouping known as Leriche syndrome.[11] This syndrome was first identified by Dr. René Leriche, a renowned French surgeon.[12]

Patients may present on an emergent visit due to sequelae of severe stenosis or an acute embolic event, causing chronic limb-threatening ischemia.[13] The diagnostic criteria for chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) are pain with rest, presence of gangrene, or lower limb ulceration for greater than two weeks in the setting of peripheral artery disease.[14]

Evaluation

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) is generally the first screening test for the diagnosis of arterial diseases due to its low cost, reliability, and non-invasive nature. This recommendation, in combination with pulse volume recordings, has been supported by the 2016 American heart association (AHA) guideline and the US preventive services task force.[15][16][17] An index of less than 0.9 is indicative of arterial disease.[18] Duplex ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) angiogram can also assist in diagnosis while providing detailed information about the location and degree of stenosis.[19][20][21][22] Magnetic resonance arteriography may subject the patient to undue contrast burden and overestimate the degree of stenosis.[19]

Blood testing should also be obtained to identify underlying risk factors. Lipid profile, hemoglobin A1c, lipoprotein A, and serum homocysteine levels may identify the etiology.[1] In the setting of thrombosis, past or present, prothrombin time (PT), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), and platelet count should be obtained. If no clear contribution from routine labs is found, further testing for anticardiolipin antibody, antithrombin III, factor II (prothrombin) C-20210a, factor V Leiden, protein C, and protein S may be of benefit. Due to its association with coronary artery disease, an electrocardiogram should also be obtained.[5]

Treatment / Management

Onset and presenting severity dictates the treatment and management of aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD). Diagnosis of chronic limb-threatening ischemia (CLTI) needs urgent intervention to prevent further necrosis and the formation of gangrene. Patient risk, limb staging, and anatomic pattern (PLAN) can assist in the staging of disease.[14](A1)

Medical management is available for non-acute cases, especially in poor surgical candidates. Primary measures include the outpatient optimization and management of diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, prothrombotic states, and tobacco use.[15][23][24] Appropriate healthy diet and exercise are also advised.[25][26] Supervised exercise programs may increase the walking distance from 180% to 340%.[27](A1)

Claudication symptoms are treatable with cilostazol or pentoxifylline. Cilostazol is a phosphodiesterase III inhibitor that may also provide benefits in graft patency and the prevention of stenosis after surgical intervention.[28] Pentoxifylline, a methylxanthine derivative, also provides relief but is less effective than cilostazol.

Anti-thrombotic Agents

The clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischemic events (CAPRIE) trial exhibited better antiplatelet management using clopidogrel over aspirin by lowering death rates from ischemic stroke, myocardial infarctions, or other vascular-related causes. Other antiplatelet agents have not been studied head-to-head, but dual antiplatelet therapy is not indicated for primary treatment. Vorapaxar, an antagonist of the protease-activated receptor (PAR-1), has shown improvements in acute limb ischemia events when administered with antiplatelet agents.[29][30] The use of vitamin K antagonists has not shown improvements in outcomes by itself or in combination with aspirin.[31][32] Subset studies of patients with peripheral artery disease have shown reduced major adverse limb events when taking rivaroxaban with aspirin.[33][34](A1)

Surgical and Endovascular Revascularization

Revascularization options include aortoiliac bypass, aortobifemoral bypass (AFB), percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA), which can be with or without stent placement, and thromboendarterectomy (TEA).[1][35][36](B2)

Open surgical revascularization bypasses the area of stenosis or occlusion through the use of a vascular conduit. Options for surgical bypass include aortoiliac bypass graft or axillary-bifemoral bypass graft.

An aortoiliac bypass graft requires greater exposure and aortic clamping, making it less suitable for some patients.[37] This surgery uses an abdominal excision to expose the infrarenal and bilateral iliac arteries. The aorta is then clamped, and a Y-shaped polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft is used to anastomose the aorta and iliac arteries. The 5-year patency rates are above 90%.[38](B3)

An axillary-bifemoral bypass is less demanding and may be used for less optimized surgical candidates. In this procedure, an extra-anatomic anastomosis is formed by tunneling the PTFE graft from the axillary artery to the bilateral common femoral arteries. Similar variations include femorofemoral bypass and axillopopliteal bypass. The AFB has a patency rate of 85-90% at five years and 75-80% at ten years, making it a more common option for surgical intervention.[1][39](B3)

Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) is a valid alternative to open surgical approaches. The PTA is completed using an inflatable balloon device over a guidewire placed across the lesion (atherosclerotic plaque), which is inflated, compressing the plaque against the native arterial wall.[38] The PTA exhibits primary patency rates of nearly 90% at one year, as well as primary assisted and secondary patency of 92.3%.[40][41][42] Research has shown that covered stents provide better outcomes than bare-metal stents.[43] The endovascular treatments have also proven beneficial for use in challenging, calcified lesions.[44](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The following differentials should always be considered in patients presenting with symptoms and signs of aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD):

- Vascular

- Arterial aneurysm

- Arterial dissection

- Embolism

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA) and Takayasu arteritis

- Venous claudication

- Non-vascular

- Musculoskeletal pain

- Neurogenic claudication

Prognosis

The prognosis is poor without intervention, though the development of self-compensating collateral circulation may improve outcomes.[45] More distal locations are associated with worse outcomes.[46] Medical management provides benefits and may prolong the time until or eliminate the need for surgical management.

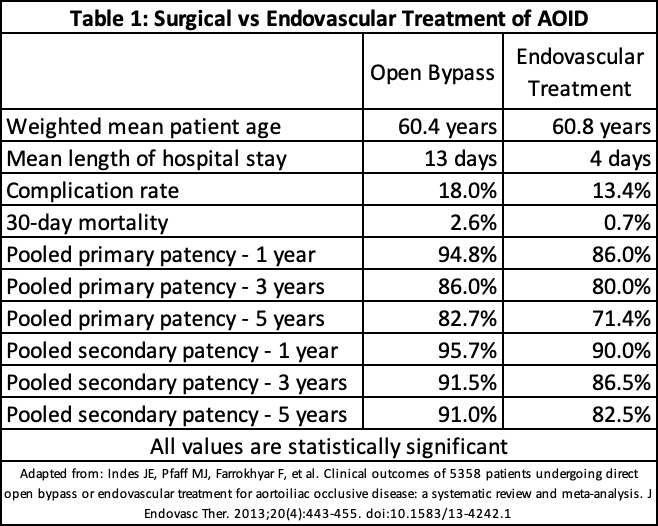

The prognosis after surgical intervention is optimistic. Thirty-day mortality was 2-3%. AFB's primary patency rates at 5 and 10 years are 86.2% and 77.6%, respectively. Ten-year limb salvage rates and overall survival is 97.7% and 91.7%, respectively.[47] The endovascular intervention has lower in-hospital mortality of 0.6%, and a primary patency rate of 96%, and 94% at one and two years, respectively.[44] A meta-analytic comparison between open bypass and endovascular intervention is provided in Table 1.[48]

Complications

Complications of untreated aortoiliac occlusive disease (AOID) include weakness, fatigue, impotence, and sexual dysfunction as a result of decreased blood flow.[1] Heart failure, myocardial infarction, gangrene, and amputation are also increased in unmanaged AOID.[49][50][51][52] Surgical and endovascular treatment risks include thrombosis of the graft, wound infection, bleeding, and complications from anesthesia.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patients are educated on lifestyle modifications and risk reduction techniques to prevent disease progression. This frequently includes smoking cessation, increased physical activity, and dietary modifications. Patients should get regular follow up after every 3-6 months. If a prosthetic graft is placed, the patients should know that the risk of getting its infection remains there for the rest of their life. Therefore prophylactic antibiotic is necessary whenever a dental procedure, gastrointestinal or urological instrumentation is planned.

Pearls and Other Issues

Because the patients with the aortoiliac occlusive disease often have other comorbidities such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, or hypertension, the preoperative workup is essential to prevent post-operative complications. In many cases, a cardiology referral is needed to assess the heart. Exercise stress testing, or nuclear myocardial perfusion scan in patients who are not able to ambulate, is recommended. Smoking should be discontinued for at least four weeks to prevent pulmonary complications of the surgery, and ongoing abstinence should be strongly encouraged.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of the aortoiliac occlusive disease requires strong interprofessional communication and care coordination, including the primary care team, vascular surgeons, interventional radiologists, and cardiologists. The education of the patient and family is essential for all involved team members to help improve patient outcomes.

Media

References

Frederick M,Newman J,Kohlwes J, Leriche syndrome. Journal of general internal medicine. 2010 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 20568019]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQi Y,Yang L,Zhang H,Liang E,Song L,Cai J,Jiang X,Zou Y,Qian H,Wu H,Zhou X,Hui R,Zheng D, The presentation and management of hypertension in a large cohort of Takayasu arteritis. Clinical rheumatology. 2018 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 29238882]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChacko S,Joseph G,Thomson V,George P,George O,Danda D, Carbon dioxide Angiography-Guided Renal-Related Interventions in Patients with Takayasu Arteritis and Renal Insufficiency. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2018 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 29549415]

Berger JS,Hochman J,Lobach I,Adelman MA,Riles TS,Rockman CB, Modifiable risk factor burden and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease in different vascular territories. Journal of vascular surgery. 2013 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 23642926]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDiehm C,Schuster A,Allenberg JR,Darius H,Haberl R,Lange S,Pittrow D,von Stritzky B,Tepohl G,Trampisch HJ, High prevalence of peripheral arterial disease and co-morbidity in 6880 primary care patients: cross-sectional study. Atherosclerosis. 2004 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 14709362]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOlin JW,Sealove BA, Peripheral artery disease: current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2010 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 20592174]

Selvin E,Erlinger TP, Prevalence of and risk factors for peripheral arterial disease in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2000. Circulation. 2004 Aug 10; [PubMed PMID: 15262830]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCriqui MH,Vargas V,Denenberg JO,Ho E,Allison M,Langer RD,Gamst A,Bundens WP,Fronek A, Ethnicity and peripheral arterial disease: the San Diego Population Study. Circulation. 2005 Oct 25; [PubMed PMID: 16246968]

Allison MA,Cushman M,Solomon C,Aboyans V,McDermott MM,Goff DC Jr,Criqui MH, Ethnicity and risk factors for change in the ankle-brachial index: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Journal of vascular surgery. 2009 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 19628357]

Creager MA,Lüscher TF,Cosentino F,Beckman JA, Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Circulation. 2003 Sep 23; [PubMed PMID: 14504252]

Brown KN,Gonzalez L, Leriche Syndrome 2020 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30855836]

Wooten C,Hayat M,du Plessis M,Cesmebasi A,Koesterer M,Daly KP,Matusz P,Tubbs RS,Loukas M, Anatomical significance in aortoiliac occlusive disease. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2014 Nov [PubMed PMID: 25065617]

Narula N,Dannenberg AJ,Olin JW,Bhatt DL,Johnson KW,Nadkarni G,Min J,Torii S,Poojary P,Anand SS,Bax JJ,Yusuf S,Virmani R,Narula J, Pathology of Peripheral Artery Disease in Patients With Critical Limb Ischemia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2018 Oct 30; [PubMed PMID: 30166084]

Conte MS, Bradbury AW, Kolh P, White JV, Dick F, Fitridge R, Mills JL, Ricco JB, Suresh KR, Murad MH, GVG Writing Group. Global vascular guidelines on the management of chronic limb-threatening ischemia. Journal of vascular surgery. 2019 Jun:69(6S):3S-125S.e40. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2019.02.016. Epub 2019 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 31159978]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceConte MS,Pomposelli FB,Clair DG,Geraghty PJ,McKinsey JF,Mills JL,Moneta GL,Murad MH,Powell RJ,Reed AB,Schanzer A,Sidawy AN, Society for Vascular Surgery practice guidelines for atherosclerotic occlusive disease of the lower extremities: management of asymptomatic disease and claudication. Journal of vascular surgery. 2015 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 25638515]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGerhard-Herman MD,Gornik HL,Barrett C,Barshes NR,Corriere MA,Drachman DE,Fleisher LA,Fowkes FGR,Hamburg NM,Kinlay S,Lookstein R,Misra S,Mureebe L,Olin JW,Patel RAG,Regensteiner JG,Schanzer A,Shishehbor MH,Stewart KJ,Treat-Jacobson D,Walsh ME,Halperin JL,Levine GN,Al-Khatib SM,Birtcher KK,Bozkurt B,Brindis RG,Cigarroa JE,Curtis LH,Fleisher LA,Gentile F,Gidding S,Hlatky MA,Ikonomidis J,Joglar J,Pressler SJ,Wijeysundera DN, 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients with Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: Executive Summary. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2017 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 28494710]

Guirguis-Blake JM,Evans CV,Redmond N,Lin JS, Screening for Peripheral Artery Disease Using the Ankle-Brachial Index: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018 Jul 10; [PubMed PMID: 29998343]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Groote P,Millaire A,Deklunder G,Marache P,Decoulx E,Ducloux G, Comparative diagnostic value of ankle-to-brachial index and transcutaneous oxygen tension at rest and after exercise in patients with intermittent claudication. Angiology. 1995 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 7702195]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAhmed S,Raman SP,Fishman EK, CT angiography and 3D imaging in aortoiliac occlusive disease: collateral pathways in Leriche syndrome. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2017 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 28401281]

Koelemay MJ,den Hartog D,Prins MH,Kromhout JG,Legemate DA,Jacobs MJ, Diagnosis of arterial disease of the lower extremities with duplex ultrasonography. The British journal of surgery. 1996 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 8665208]

Romano M,Mainenti PP,Imbriaco M,Amato B,Markabaoui K,Tamburrini O,Salvatore M, Multidetector row CT angiography of the abdominal aorta and lower extremities in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease: diagnostic accuracy and interobserver agreement. European journal of radiology. 2004 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 15145492]

Menke J,Larsen J, Meta-analysis: Accuracy of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography for assessing steno-occlusions in peripheral arterial disease. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Sep 7; [PubMed PMID: 20820041]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGerhard-Herman MD,Gornik HL,Barrett C,Barshes NR,Corriere MA,Drachman DE,Fleisher LA,Fowkes FG,Hamburg NM,Kinlay S,Lookstein R,Misra S,Mureebe L,Olin JW,Patel RA,Regensteiner JG,Schanzer A,Shishehbor MH,Stewart KJ,Treat-Jacobson D,Walsh ME, 2016 AHA/ACC Guideline on the Management of Patients With Lower Extremity Peripheral Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017 Mar 21; [PubMed PMID: 27840333]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEckel RH,Jakicic JM,Ard JD,de Jesus JM,Houston Miller N,Hubbard VS,Lee IM,Lichtenstein AH,Loria CM,Millen BE,Nonas CA,Sacks FM,Smith SC Jr,Svetkey LP,Wadden TA,Yanovski SZ,Kendall KA,Morgan LC,Trisolini MG,Velasco G,Wnek J,Anderson JL,Halperin JL,Albert NM,Bozkurt B,Brindis RG,Curtis LH,DeMets D,Hochman JS,Kovacs RJ,Ohman EM,Pressler SJ,Sellke FW,Shen WK,Smith SC Jr,Tomaselli GF, 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014 Jun 24; [PubMed PMID: 24222015]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWeitz JI,Byrne J,Clagett GP,Farkouh ME,Porter JM,Sackett DL,Strandness DE Jr,Taylor LM, Diagnosis and treatment of chronic arterial insufficiency of the lower extremities: a critical review. Circulation. 1996 Dec 1; [PubMed PMID: 8941154]

Gardner AW,Poehlman ET, Exercise rehabilitation programs for the treatment of claudication pain. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995 Sep 27; [PubMed PMID: 7674529]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBouwens E,Klaphake S,Weststrate KJ,Teijink JA,Verhagen HJ,Hoeks SE,Rouwet EV, Supervised exercise therapy and revascularization: Single-center experience of intermittent claudication management. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2019 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 30795714]

Tara S,Kurobe H,de Dios Ruiz Rosado J,Best CA,Shoji T,Mahler N,Yi T,Lee YU,Sugiura T,Hibino N,Partida-Sanchez S,Breuer CK,Shinoka T, Cilostazol, Not Aspirin, Prevents Stenosis of Bioresorbable Vascular Grafts in a Venous Model. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2015 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 26183618]

Bonaca MP,Creager MA,Olin J,Scirica BM,Gilchrist IC Jr,Murphy SA,Goodrich EL,Braunwald E,Morrow DA, Peripheral Revascularization in Patients With Peripheral Artery Disease With Vorapaxar: Insights From the TRA 2°P-TIMI 50 Trial. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2016 Oct 24; [PubMed PMID: 27765312]

Morrow DA,Braunwald E,Bonaca MP,Ameriso SF,Dalby AJ,Fish MP,Fox KA,Lipka LJ,Liu X,Nicolau JC,Ophuis AJ,Paolasso E,Scirica BM,Spinar J,Theroux P,Wiviott SD,Strony J,Murphy SA, Vorapaxar in the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Apr 12; [PubMed PMID: 22443427]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceThe effects of oral anticoagulants in patients with peripheral arterial disease: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the Warfarin and Antiplatelet Vascular Evaluation (WAVE) trial, including a meta-analysis of trials. American heart journal. 2006 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 16368284]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAnand S,Yusuf S,Xie C,Pogue J,Eikelboom J,Budaj A,Sussex B,Liu L,Guzman R,Cina C,Crowell R,Keltai M,Gosselin G, Oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy and peripheral arterial disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2007 Jul 19; [PubMed PMID: 17634457]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEikelboom JW,Connolly SJ,Bosch J,Dagenais GR,Hart RG,Shestakovska O,Diaz R,Alings M,Lonn EM,Anand SS,Widimsky P,Hori M,Avezum A,Piegas LS,Branch KRH,Probstfield J,Bhatt DL,Zhu J,Liang Y,Maggioni AP,Lopez-Jaramillo P,O'Donnell M,Kakkar AK,Fox KAA,Parkhomenko AN,Ertl G,Störk S,Keltai M,Ryden L,Pogosova N,Dans AL,Lanas F,Commerford PJ,Torp-Pedersen C,Guzik TJ,Verhamme PB,Vinereanu D,Kim JH,Tonkin AM,Lewis BS,Felix C,Yusoff K,Steg PG,Metsarinne KP,Cook Bruns N,Misselwitz F,Chen E,Leong D,Yusuf S, Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2017 Oct 5; [PubMed PMID: 28844192]

Anand SS,Bosch J,Eikelboom JW,Connolly SJ,Diaz R,Widimsky P,Aboyans V,Alings M,Kakkar AK,Keltai K,Maggioni AP,Lewis BS,Störk S,Zhu J,Lopez-Jaramillo P,O'Donnell M,Commerford PJ,Vinereanu D,Pogosova N,Ryden L,Fox KAA,Bhatt DL,Misselwitz F,Varigos JD,Vanassche T,Avezum AA,Chen E,Branch K,Leong DP,Bangdiwala SI,Hart RG,Yusuf S, Rivaroxaban with or without aspirin in patients with stable peripheral or carotid artery disease: an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Jan 20; [PubMed PMID: 29132880]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMetcalfe MJ,Natarajan R,Selvakumar S, Use of extraperitoneal iliac artery endarterectomy in the endovascular era. Vascular. 2008 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 19344587]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKrankenberg H,Schlüter M,Schwencke C,Walter D,Pascotto A,Sandstede J,Tübler T, Endovascular reconstruction of the aortic bifurcation in patients with Leriche syndrome. Clinical research in cardiology : official journal of the German Cardiac Society. 2009 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 19685001]

Rutherford RB, Options in the surgical management of aorto-iliac occlusive disease: a changing perspective. Cardiovascular surgery (London, England). 1999 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 10073753]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKang N,Kenel-Pierre S,DeAmorim H,Karwowski J,Bornak A, Endovascular Aortoiliac Revascularization in a Patient with Spinal Cord Injury and Hip Contracture. Annals of vascular surgery. 2018 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 28893707]

Pursell R,Sideso E,Magee TR,Galland RB, Critical appraisal of femorofemoral crossover grafts. The British journal of surgery. 2005 May; [PubMed PMID: 15810055]

Ichihashi S,Higashiura W,Itoh H,Sakaguchi S,Nishimine K,Kichikawa K, Long-term outcomes for systematic primary stent placement in complex iliac artery occlusive disease classified according to Trans-Atlantic Inter-Society Consensus (TASC)-II. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 21215582]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVan Haren RM,Goldstein LJ,Velazquez OC,Karmacharya J,Bornak A, Endovascular treatment of TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus D aortoiliac occlusive disease using unibody bifurcated endografts. Journal of vascular surgery. 2017 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 27765483]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGroot Jebbink E,Holewijn S,Slump CH,Lardenoije JW,Reijnen MMPJ, Systematic Review of Results of Kissing Stents in the Treatment of Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease. Annals of vascular surgery. 2017 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 28390920]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMwipatayi BP,Thomas S,Wong J,Temple SE,Vijayan V,Jackson M,Burrows SA, A comparison of covered vs bare expandable stents for the treatment of aortoiliac occlusive disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 21906903]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePiffaretti G,Fargion AT,Dorigo W,Pulli R,Gattuso A,Bush RL,Pratesi C, Outcomes From the Multicenter Italian Registry on Primary Endovascular Treatment of Aortoiliac Occlusive Disease. Journal of endovascular therapy : an official journal of the International Society of Endovascular Specialists. 2019 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 31331235]

Morotti A,Busso M,Cinardo P,Bonomo K,Angelino V,Cardinale L,Veltri A,Guerrasio A, When collateral vessels matter: asymptomatic Leriche syndrome. Clinical case reports. 2015 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 26576282]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAboyans V,Desormais I,Lacroix P,Salazar J,Criqui MH,Laskar M, The general prognosis of patients with peripheral arterial disease differs according to the disease localization. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2010 Mar 2; [PubMed PMID: 20185041]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLee GC,Yang SS,Park KM,Park Y,Kim YW,Park KB,Park HS,Do YS,Kim DI, Ten year outcomes after bypass surgery in aortoiliac occlusive disease. Journal of the Korean Surgical Society. 2012 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 22708098]

Indes JE,Pfaff MJ,Farrokhyar F,Brown H,Hashim P,Cheung K,Sosa JA, Clinical outcomes of 5358 patients undergoing direct open bypass or endovascular treatment for aortoiliac occlusive disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of endovascular therapy : an official journal of the International Society of Endovascular Specialists. 2013 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 23914850]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKeller K,Beule J,Oliver Balzer J,Coldewey M,Munzel T,Dippold W,Wild P, A 56-year-old man with co-prevalence of Leriche syndrome and dilated cardiomyopathy: case report and review. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift. 2014 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 24343041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKashou AH,Braiteh N,Zgheib A,Kashou HE, Acute aortoiliac occlusive disease during percutaneous transluminal angioplasty in the setting of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2018 Jan 11; [PubMed PMID: 29321037]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJOHNSON JK, Ascending thrombosis of abdominal aorta as fatal complication of Leriche's syndrome. A.M.A. archives of surgery. 1954 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 13206556]

Bredahl K,Jensen LP,Schroeder TV,Sillesen H,Nielsen H,Eiberg JP, Mortality and complications after aortic bifurcated bypass procedures for chronic aortoiliac occlusive disease. Journal of vascular surgery. 2015 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 26115920]