Indications

Cannabinoids, broadly speaking, are a class of biological compounds that bind to cannabinoid receptors. They are most frequently sourced from and associated with the plants of the Cannabis genus, including Cannabis sativa, Cannabis indica, and Cannabis ruderalis. The earliest known use of cannabinoids dates back 5,000 years ago in modern Romania, while the documentation of the earliest medical dates back to around 400 AD.[1][2] However, formal extraction, isolation, and structural elucidation of cannabinoids have taken place relatively recently in the late 19th and early 20th centuries [1]. Since then, numerous advancements have been made in further isolating naturally occurring cannabinoids, synthesizing artificial equivalents, and discovering the endogenous endocannabinoid system in mammals, reptiles, fish, and birds.[3][4] Cannabinoids, in the context of medicine, come in three forms:

- Phytocannabinoids - derived naturally from flora

- Endocannabinoids - produced endogenously

- Synthetic Cannabinoids – created artificially

Of all known cannabinoids (hundreds of which have been isolated and identified), arguably the most commonly notable are the phytocannabinoids tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) - the former being responsible for Cannabis’s psychoactive effects. Throughout their storied history, cannabinoids have been renowned for their psychotropic and physiological effects. In tandem, the effects, as mentioned above, have made them the target of medical, cultural, and recreational uses, of which the former will be the focus of this article. Cannabinoids are frequently the targets of pharmaceutical innovation, with most being either structurally related to or mimicking the ligand-receptor activity of THC and CBD. These biochemical innovations have found extensive application in clinical studies for a variety of diseases, where cannabinoids have shown mild to strong efficacy:

- Chronic pain, opioid dependence[5][6]

- Epilepsy (e.g., Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome)[7]

- Appetite stimulation in HIV/AIDS and cancer patients[8]

- Tourette syndrome[9]

- Multiple sclerosis[10]

- Chemotherapy-related nausea/vomiting[11]

Clinical studies notwithstanding, in the United States (US), only a small number of cannabinoids have been approved for medical use by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Those are:

- Dronabinol

- Nabilone

- Cannabidiol

Finally, as a point of clarification for this review, Cannabis refers to the plants mentioned above of the Cannabis genus, marijuana refers to parts of Cannabis containing notable concentrations of THC, and hemp refers to cannabis plants often designated for industrial use containing less than legal threshold of THC in the US. These distinctions are important, inasmuch as many people, both laypersons, and even medical personnel, blur the lines between them.

This article focuses on systemically ingested cannabinoid formulations and does not address topical cannabinoid products, which are available over the counter.

Mechanism of Action

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Mechanism of Action

Cannabinoids function by stimulating two receptors, cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1) and type 2 (CB2), within the endocannabinoid system. This system is a complex network of organs throughout the body, expressing the cannabinoid receptors and playing a homeostatic role. Functions of the endocannabinoid system include pain,[12] memory,[13] movement,[14] appetite,[15] metabolism,[16] lacrimation/salivation,[17] immunity,[18] and even cardiopulmonary function.[18] It bears mentioning that the vast majority of end-effects from cannabinoids, including psychotropics, are from activation of CB1, with CB2 serving more important roles in immune and inflammatory functions.

Endogenously, endocannabinoids serve as neuro-regulatory modulators responsible for retrograde neurotransmission. Here, a post-synaptic neuron releases endocannabinoids that bind to predominantly CB1 receptors on the presynaptic neuron. This binding results in inhibited presynaptic calcium channel activation and subsequent presynaptic neurotransmitter release.[19] If the presynaptic neurotransmitters are predominantly inhibitory such as GABA, the net effect is excitatory and vice versa.

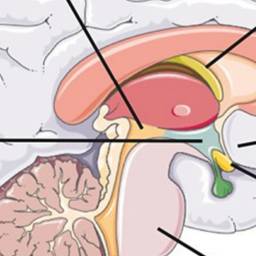

Binding to the different parts of the central nervous system mediates different psychotropic properties of cannabinoids, particularly THC (see Image. Central Nervous System, Effects of Tetrahydrocannabinol). These areas and end-effects include [19]:

- Hippocampus: impairment of short-term memory

- Neocortex: impairment of judgment and sensation

- Basal ganglia: altered reaction time and movement

- Hypothalamus: increased appetite

- Nucleus accumbens: euphoria

- Amygdala: panic and paranoia

- Cerebellum: ataxia

- Brainstem: anti-emesis

- Spinal cord: analgesia

Other end-effects of CB1 activation peripherally include dry mouth, conjunctivitis, tachycardia, hypotension, and bradypnea.

Administration

Depending on the cannabinoid, the route of administration will vary. Medical cannabinoids are generally administered orally as a capsule or liquid suspension. Dronabinol is available as a capsule in 2.5mg, 5mg, and 10mg strengths in addition to an oral 5mg/mL formulation. The medication is generally taken twice daily an hour before meals with titration from the initial dose performed gradually based on tolerability and response.[20] Nabilone is available as a 1mg capsule and may be taken 2 to 3 times daily, depending on the provider and patient preference. Finally, cannabidiol is available as an oral solution at 100 mg/mL and may be taken twice daily, starting at 2.5 mg/kg/day and titrated as patient response and tolerability dictate.

Cannabinoids may also be administered orally via incorporation in consumed food products such as infused teas or oils or via inhalation by smoking cannabis or marijuana.[20] Products containing THC are almost always illicit, carrying a Schedule I classification by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), and are therefore are available only on black markets. However, CBD has gained popularity in recent years and is available over the counter. Although smoking cannabis is traditionally the most common method of cannabinoid administration, vaporization with e-cigarettes is continuing to become more popular, offering a more rapid, less carcinogenic method of delivering cannabinoids from the lungs into the bloodstream.[21] Finally, although sublingual, rectal, ocular, transdermal, and aerosol deliveries have seen research, a paucity of literature regarding their use has mitigated their practical application.

Adverse Effects

Adverse effects of cannabinoids exist on a spectrum, ranging from mild to lethal, and vary on the mode associated risks of administration. The most frequently encountered side effects of cannabinoids are generally those from recreational sources.[1] Over the short-term, mild effects include euphoria, anxiolysis, tachycardia, visuotemporal distortion, sensory amplification, tachycardia, postural hypotension, conjunctivitis, hunger, and dry throat, mouth, and eyes.[22] More severe symptoms include panic attacks, myoclonus, psychosis, hyperemesis, inhalation burns, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and bronchospasm – any one of which may result in hospitalization or the necessity of emergency medical services.[1][19]

Over the long-term, heavy cannabinoid abuse has correlated in numerous adverse health conditions, including:

- Addiction, altered brain development, and cognitive impairment in adolescents[23]

- Chronic bronchitis, ARDS, lung cancer[24]

- Increased risk for myocardial infarction, stroke, and thromboembolic events[24]

- Exacerbation of mood disorders (anxiety, depression) and psychotic disorders (schizophrenia)[25][26]

- Exacerbation of neurodegenerative diseases (multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease)[1]

In addition to the above, other adverse effects of cannabinoids include hypersensitivity reactions to active cannabinoids in specific formulations or constituent components (e.g., capsules or inactive additives) or disulfiram reaction (nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and headache) with concurrent disulfiram or metronidazole use.

Contraindications

Contraindications to cannabinoids are few but include hypersensitivity to specific medications, cannabinoids generally, constituent components of specific formulations (e.g., sesame seed oil in capsules or other inactive ingredients), and recent administration of products containing disulfiram or metronidazole within two weeks.[27] Some have also posited that concurrent anxiety or mood disorders or personal/family history of psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia may also be a contraindication.[28]

Monitoring

Cannabinoids are generally not monitored regularly except for some patients who require routine drug screening or present with suspicion of drug overdose or abuse. The most common diagnostic test for cannabinoid detection is the urine drug screen (UDS), which detects THC and CBD metabolites. Otherwise, owing to differences in metabolism, mode of administration detection, and frequency of use may cause detection times to vary significantly between patients. Besides UDS, monitoring is otherwise based mainly on symptoms of intoxication and overdose.

Toxicity

In the event of cannabinoid drug toxicity, as described above, treatment and management are largely supportive and focused on symptom relief.[29][30] Psychosis and agitation should have treatment with benzodiazepines and antipsychotics, preferably of the second-generation or atypical class, due to their lower risk of extrapyramidal effects. An electrocardiogram can rule out myocardial ischemia or dysrhythmias, and if present, the clinician should start empiric therapy with rate-controlling agents.[30] Hyperemesis should receive appropriate medication with antiemetics provided that the risk of dysrhythmias is sufficiently low. Clinicians need to address seizure activity with benzodiazepines and/or anticonvulsant agents as tolerated. Finally, signs of pulmonary compromise should necessitate supportive measures such as oxygen via nasal cannula, positive airway pressure ventilation, and endotracheal intubation if severe enough.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cannabinoids have served numerous roles in medicine, culture, and recreation for almost as long as recorded human history. With pharmaceutical and illicit forms available to patients, healthcare providers and other interprofessional healthcare team members must be equipped with the knowledge to identify symptoms of cannabinoid abuse and toxicity and take steps to mitigate adverse outcomes. However, medical professionals must also understand medical conditions that may respond to treatment with appropriately dosed and administered cannabinoids.

Cannabinoids can be recommended or prescribed by clinicians (physicians such as MDs and DOs, and mid-level providers like NPs and PAs) in accordance with the current evidence-based information. Nursing staff can also play a role in counseling patients and answering questions. As with any medication, the pharmacist should verify dosing, check for any potential drug-drug interactions, perform complete medication reconciliation, and provide any additional counseling the patient may need regarding dosing, administration, monitoring for adverse events, and answer any questions the patient may have. This approach demonstrates how all members of today's integrated, interprofessional health team must demonstrate full engagement regarding the entire spectrum of cannabinoids' ability to help and harm patients so that they can achieve an optimal balance. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bridgeman MB, Abazia DT. Medicinal Cannabis: History, Pharmacology, And Implications for the Acute Care Setting. P & T : a peer-reviewed journal for formulary management. 2017 Mar:42(3):180-188 [PubMed PMID: 28250701]

Zias J, Stark H, Sellgman J, Levy R, Werker E, Breuer A, Mechoulam R. Early medical use of cannabis. Nature. 1993 May 20:363(6426):215 [PubMed PMID: 8387642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcPartland JM, Agraval J, Gleeson D, Heasman K, Glass M. Cannabinoid receptors in invertebrates. Journal of evolutionary biology. 2006 Mar:19(2):366-73 [PubMed PMID: 16599912]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMechoulam R,Fride E,Di Marzo V, Endocannabinoids. European journal of pharmacology. 1998 Oct 16; [PubMed PMID: 9831287]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRomero-Sandoval EA, Kolano AL, Alvarado-Vázquez PA. Cannabis and Cannabinoids for Chronic Pain. Current rheumatology reports. 2017 Oct 5:19(11):67. doi: 10.1007/s11926-017-0693-1. Epub 2017 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 28983880]

Sohler NL, Starrels JL, Khalid L, Bachhuber MA, Arnsten JH, Nahvi S, Jost J, Cunningham CO. Cannabis Use is Associated with Lower Odds of Prescription Opioid Analgesic Use Among HIV-Infected Individuals with Chronic Pain. Substance use & misuse. 2018 Aug 24:53(10):1602-1607. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1416408. Epub 2018 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 29338578]

Morano A, Fanella M, Albini M, Cifelli P, Palma E, Giallonardo AT, Di Bonaventura C. Cannabinoids in the Treatment of Epilepsy: Current Status and Future Prospects. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment. 2020:16():381-396. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S203782. Epub 2020 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 32103958]

Badowski ME, Yanful PK. Dronabinol oral solution in the management of anorexia and weight loss in AIDS and cancer. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2018:14():643-651. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S126849. Epub 2018 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 29670357]

Abi-Jaoude E, Chen L, Cheung P, Bhikram T, Sandor P. Preliminary Evidence on Cannabis Effectiveness and Tolerability for Adults With Tourette Syndrome. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2017 Fall:29(4):391-400. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16110310. Epub 2017 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 28464701]

Nielsen S, Germanos R, Weier M, Pollard J, Degenhardt L, Hall W, Buckley N, Farrell M. The Use of Cannabis and Cannabinoids in Treating Symptoms of Multiple Sclerosis: a Systematic Review of Reviews. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2018 Feb 13:18(2):8. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0814-x. Epub 2018 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 29442178]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMay MB, Glode AE. Dronabinol for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting unresponsive to antiemetics. Cancer management and research. 2016:8():49-55. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S81425. Epub 2016 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 27274310]

Calignano A, La Rana G, Loubet-Lescoulié P, Piomelli D. A role for the endogenous cannabinoid system in the peripheral control of pain initiation. Progress in brain research. 2000:129():471-82 [PubMed PMID: 11098711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCastellano C, Rossi-Arnaud C, Cestari V, Costanzi M. Cannabinoids and memory: animal studies. Current drug targets. CNS and neurological disorders. 2003 Dec:2(6):389-402 [PubMed PMID: 14683467]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRodríguez de Fonseca F, Del Arco I, Martín-Calderón JL, Gorriti MA, Navarro M. Role of the endogenous cannabinoid system in the regulation of motor activity. Neurobiology of disease. 1998 Dec:5(6 Pt B):483-501 [PubMed PMID: 9974180]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGómez R, Navarro M, Ferrer B, Trigo JM, Bilbao A, Del Arco I, Cippitelli A, Nava F, Piomelli D, Rodríguez de Fonseca F. A peripheral mechanism for CB1 cannabinoid receptor-dependent modulation of feeding. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2002 Nov 1:22(21):9612-7 [PubMed PMID: 12417686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDi Marzo V, Melck D, Bisogno T, De Petrocellis L. Endocannabinoids: endogenous cannabinoid receptor ligands with neuromodulatory action. Trends in neurosciences. 1998 Dec:21(12):521-8 [PubMed PMID: 9881850]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNallapaneni A, Liu J, Karanth S, Pope C. Pharmacological enhancement of endocannabinoid signaling reduces the cholinergic toxicity of diisopropylfluorophosphate. Neurotoxicology. 2008 Nov:29(6):1037-43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.08.001. Epub 2008 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 18765251]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePandey R, Mousawy K, Nagarkatti M, Nagarkatti P. Endocannabinoids and immune regulation. Pharmacological research. 2009 Aug:60(2):85-92. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.03.019. Epub 2009 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 19428268]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMouhamed Y,Vishnyakov A,Qorri B,Sambi M,Frank SS,Nowierski C,Lamba A,Bhatti U,Szewczuk MR, Therapeutic potential of medicinal marijuana: an educational primer for health care professionals. Drug, healthcare and patient safety. 2018; [PubMed PMID: 29928146]

Taylor BN, Mueller M, Sauls RS. Cannaboinoid Antiemetic Therapy. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571051]

Hartman RL, Brown TL, Milavetz G, Spurgin A, Gorelick DA, Gaffney G, Huestis MA. Controlled Cannabis Vaporizer Administration: Blood and Plasma Cannabinoids with and without Alcohol. Clinical chemistry. 2015 Jun:61(6):850-69. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.238287. Epub 2015 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 26019183]

Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. The New England journal of medicine. 2014 Jun 5:370(23):2219-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1402309. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24897085]

Curran HV, Freeman TP, Mokrysz C, Lewis DA, Morgan CJ, Parsons LH. Keep off the grass? Cannabis, cognition and addiction. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2016 May:17(5):293-306. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.28. Epub 2016 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 27052382]

Joshi M, Joshi A, Bartter T. Marijuana and lung diseases. Current opinion in pulmonary medicine. 2014 Mar:20(2):173-9. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24384575]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Graaf R, Radovanovic M, van Laar M, Fairman B, Degenhardt L, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Bruffaerts R, de Girolamo G, Fayyad J, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Kostychenko S, Lépine JP, Matschinger H, Mora ME, Neumark Y, Ormel J, Posada-Villa J, Stein DJ, Tachimori H, Wells JE, Anthony JC. Early cannabis use and estimated risk of later onset of depression spells: Epidemiologic evidence from the population-based World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. American journal of epidemiology. 2010 Jul 15:172(2):149-59. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq096. Epub 2010 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 20534820]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBlanco C, Hasin DS, Wall MM, Flórez-Salamanca L, Hoertel N, Wang S, Kerridge BT, Olfson M. Cannabis Use and Risk of Psychiatric Disorders: Prospective Evidence From a US National Longitudinal Study. JAMA psychiatry. 2016 Apr:73(4):388-95. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3229. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26886046]

. Dronabinol. Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®). 2006:(): [PubMed PMID: 30000656]

Beaulieu P, Boulanger A, Desroches J, Clark AJ. Medical cannabis: considerations for the anesthesiologist and pain physician. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 2016 May:63(5):608-24. doi: 10.1007/s12630-016-0598-x. Epub 2016 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 26850063]

Kelly BF, Nappe TM. Cannabinoid Toxicity. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489164]

Crippa JA, Derenusson GN, Chagas MH, Atakan Z, Martín-Santos R, Zuardi AW, Hallak JE. Pharmacological interventions in the treatment of the acute effects of cannabis: a systematic review of literature. Harm reduction journal. 2012 Jan 25:9():7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-9-7. Epub 2012 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 22273390]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence