Introduction

The inferior vena cava (IVC) is a large retroperitoneal vessel formed by the confluence of the right and left common iliac veins. Anatomically this usually occurs at the L5 vertebral level. The IVC lies along the right anterolateral aspect of the vertebral column and passes through the central tendon of the diaphragm around the T8 vertebral level. The IVC is a large blood vessel responsible for transporting deoxygenated blood from the lower extremities and abdomen back to the right atrium of the heart. It has the largest diameter of the venous system and is a thin-walled vessel. These anatomic characteristics make it ideal for transporting large quantities of venous blood. Many veins contain one-way valves to ensure the forward flow of blood back toward the heart. The IVC, however, does not contain such valves, and forward flow to the heart is driven by the differential pressure created by normal respiration. As the diaphragm contracts and creates negative pressure in the chest for the lungs to fill with air, this pressure gradient pulls the venous blood from the abdominal IVC into the thoracic IVC and subsequently into the right heart. The IVC enters the right atrium of the heart after coursing through the diaphragm, entering the posterior inferior aspect of the atrium. The IVC enters the right atrium inferior to the entrance of the superior vena cava (SVC).

The IVC is a mostly symmetric vessel with a few exceptions. Due to the IVC residing on the right side of the vertebral column the vessels entering the IVC from the left side of the body, like the left renal vein, are longer than their anatomic counterparts on the right. Other left-sided veins, like the left adrenal and left gonadal vein, first join the left renal vein before joining the IVC and continuing as venous flow returning to the heart. This differs from the right side of the body where the right adrenal and right gonadal vein directly join the IVC without first joining the right renal vein. Anatomic variants venous of anatomy involving both right and left sides have been described.[1]

Blood from the left and right femoral veins enters the IVC via the left and right common iliac veins, respectively. Blood from the abdominal viscera travels into the portal vein and enters the IVC via the hepatic veins after traversing the liver and its sinusoids. Venous blood from the abdominal wall reaches the IVC through lumbar veins. Ascending lumbar veins connect lumbar veins to the azygos vein and this provides some collateral circulation between the inferior vena cava and the superior vena cava.[2] This potential for a collateral flow could be critical if either of the larger veins becomes obstructed.

Below is a list of (most common) vertebral levels at which different veins enter the IVC.

- T8: Hepatic veins, inferior phrenic veins

- L1: Right suprarenal vein, renal veins

- L2: Right gonadal vein

- L1-L5: Lumbar vertebral veins

- L5: Right and left common iliac veins

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The inferior vena cava is ultimately responsible for the transport of almost all venous blood (deoxygenated) from the abdomen and lower extremities back to the right side of the heart for oxygenation.

Embryology

During the fifth week of embryologic development, there are 3 major identifiable pairs of veins: the vitelline veins, the umbilical veins, and the cardinal veins. Only the vitelline veins and the cardinal veins contribute to the formation of the inferior vena cava in the human adult.

The vitelline veins, also known as the omphalomesenteric veins, form a plexus around the primitive duodenum and pass through the septum transversum to drain venous blood from this area. As liver cords grow into the septum transversum a dense, sinusoidal network forms and the left vitelline vein regresses. The sinusoidal network becomes the hepatic sinusoidal system, and the plexus around the duodenum becomes the portal vein. While the left vitelline vein regresses, the right vitelline vein becomes more prominent and is called the hepatocardiac channel.[3]

The hepatocardiac channel forms the hepatocardiac portion of the inferior vena cava.

The cardinal veins, which are primarily responsible for venous drainage of the early embryo, are paired veins divided into anterior and posterior segments. The anterior cardinal veins drain the cephalad portion of the embryo, and the posterior cardinal veins drain the caudal portion. Sometime between the fourth and fifth weeks of embryologic development the subcardinal veins, the sacrocardinal veins, and the supracardinal veins are derived from the cardinal veins. These derivatives of the cardinal veins play an important role in the formation of the inferior vena cava.

The supracardinal veins assume the role of the posterior cardinal veins and drain the body wall by becoming intercostal veins. Supracardinal veins do not directly contribute to the formation of the inferior vena cava.

The left subcardinal veins coalesce to form the left renal vein and left gonadal vein. The right subcardinal vein becomes the renal portion of the inferior vena cava.

The sacrocardinal veins coalesce to form the left common iliac vein. The right sacrocardinal vein becomes the sacrocardinal segment of the inferior vena cava.

The union of the renal portion of the inferior vena cava with the hepatocardiac portion of the inferior vena cava completes the embryologic formation of the inferior vena cava with its hepatic, renal, and sacrocardinal segments.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood supply to the inferior vena cava is derived partially from the deoxygenated blood it carries towards the heart and partially supplied by the vasa vasorum that penetrates the tunica adventitia of the vessel.[5]

Nerves

The inferior vena cava receives autonomic innervation from the splanchnic nerves.[6] This innervation serves to alter the diameter of the IVC via interactions with alpha-1, alpha-2, and beta-2 receptors.

Muscles

As in all vasculature, the inferior vena cava contains three layers: the tunica intima, the tunica media, and the tunica adventitia. The tunica media layer of the inferior vena cava contains smooth muscle responsive to the input from the nervous system.[6] No other muscles are found in the inferior vena cava.

Physiologic Variants

There are many physiologic variants of the IVC.[1] Compared to the arterial system the venous system is much more susceptible to congenital malformations, many of which remain asymptomatic throughout a patient's life. If symptoms are present, they are often vague and include abdominal pain or low back pain. Some of the more clinically significant physiologic variants are listed below.

- Left Inferior Vena Cava: This anomaly is caused by the regression of the right supracardinal vein and the persistence of the left supracardinal vein. The left inferior vena cava is joined by the left renal vein and then crosses anterior to the aorta before it joins the right atrium, forming a normal pre-renal IVC. This anomaly has a suspected prevalence of 0.2% to 0.5%.

- Double Inferior Vena Cava: This anomaly is caused by the persistence of both the left and right supracardinal veins. A prevalence of 0.2% to 0.3% is suspected. [7]

- Intrahepatic Inferior Vena Cava Agenesis: Congenital anomaly resulting in the lack of the intrahepatic IVC. Intrahepatic venous supply bypasses the hepatic IVC through the azygos/hemiazygos venous system.[2]

- Absent Infrarenal Inferior Vena Cava: This is the rarest of the physiologic caval anomalies. The suspected and currently accepted etiology of absent infrarenal inferior vena cava is intrauterine or perinatal thrombosis and resultant degeneration of the infrarenal IVC.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Any surgical procedure involving the thoracic cavity or abdomen requires attention to the location, condition, and orientation of the inferior vena cava in relation to other structures and organs. Anatomic variants of the IVC are not common, but awareness of their presence and associated diseases/other common co-existing anomalies is important. Unmitigated injury to the IVC, either iatrogenic or resultant of trauma, results in rapid exsanguination. The principles of repair for injury to the IVC is similar to other vessel injuries. Although there are varying techniques depending on the location of the injury and the experience of the surgeon the primary objective is proximal and distal control of the IVC followed by some type of repair. In a life-threatening situation, IVC ligation has been successfully undertaken. This is a last resort procedure and comes with significant morbidity if the patient survives.

Clinical Significance

Although there is some controversy over indications, recurrent deep venous thromboses and consequent pulmonary emboli refractory to treatment with anticoagulation may require placement of an inferior vena cava filter.[9] Certain institutions also advocate for IVC filter placement for high-risk trauma patients (even without documented clots). IVC filters may be permanent or retrievable, although data suggest that only a fraction of the retrievable filters are later removed. Anatomic variations from the norm require careful attention to detail and understanding of their manifestations and potential complications during procedures.

IVC thrombosis is a difficult clinical scenario. Although it can be asymptomatic IVC thrombosis can also present with a myriad of symptoms. These are usually non-specific like abdominal or back pain; but may also include leg cramping, swelling, or pain. Treatment is based on patient condition/symptoms and can include anticoagulation, clot, and/or filter (if present) removal via Interventional Radiology techniques or rarely open surgical techniques. The most common cause of IVC thrombosis in a patient without anatomic variants is the previous IVC filter placement.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Embryology, development of venous system, Left and Right innominate, Internal and External Jugular, Superior vena cava, Duct of Cuvier, Left cardinal, Left Suprarenal and Renal, inferior vena cava; Prerenal and Postrenal parts, Left common iliac, External Iliac, Hypogastric

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

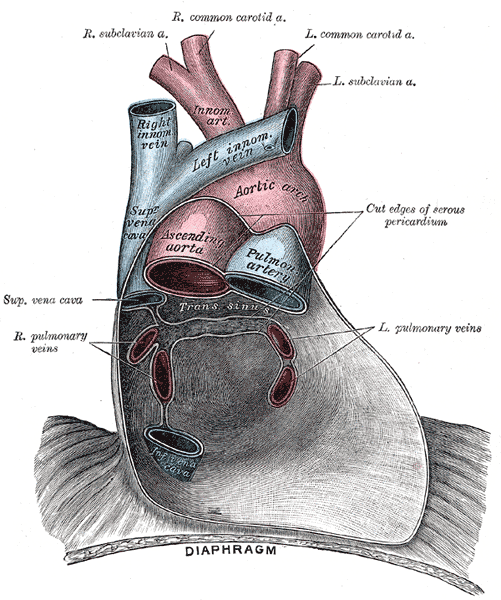

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pericardium anatomy, Right Subclavian Artery, Right Common Carotid Artery, Left Common Carotid Artery, Left Subclavian Artery, Innominate Artery, Right Innominate vein, Left innominate vein, Aortic Arch, Superior Vena cava, Ascending Aorta, Pulmonary Artery, Left and Right Pulmonary veins, Inferior Vena Cava, Diaphragm

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Retroperitoneal Organs. This image shows the anatomical relationships between the diaphragm, right and left suprarenal glands, right and left gonadal vessels, celiac trunk, superior and inferior mesenteric arteries, inferior phrenic arteries, internal spermatic vessels, median sacral arteries, left and right kidneys, inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta, right and left renal vessels, transversus abdominis, quadratus lumborum, right and left common Iliac vessels, psoas major, and iliacus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

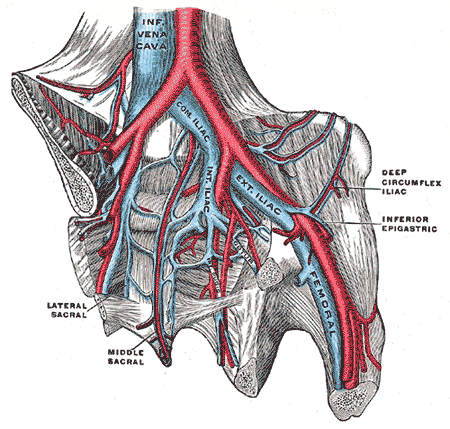

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pelvic Veins. Pelvic veins include the inferior vena cava, internal iliac vein, common iliac vein, external iliac vein, femoral vein, deep circumflex iliac vein, middle sacral vein, and lateral sacral vein.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

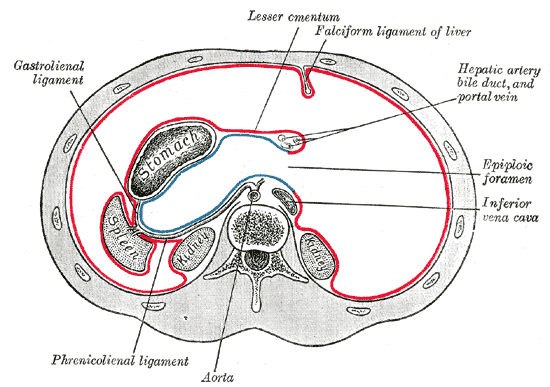

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Abdomen, Horizontal disposition of the peritoneum in the upper part of the abdomen, Phrenico Lienal ligament, Aorta, Inferior Vena cava, Epiploic foramen, Hepatic artery bile duct and portal vein, Falciform ligament of liver, Lesser omentum, Gastrolienal ligament

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Petik B. Inferior vena cava anomalies and variations: imaging and rare clinical findings. Insights into imaging. 2015 Dec:6(6):631-9. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0431-z. Epub 2015 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 26373648]

Piciucchi S, Barone D, Sanna S, Dubini A, Goodman LR, Oboldi D, Bertocco M, Ciccotosto C, Gavelli G, Carloni A, Poletti V. The azygos vein pathway: an overview from anatomical variations to pathological changes. Insights into imaging. 2014 Oct:5(5):619-28. doi: 10.1007/s13244-014-0351-3. Epub 2014 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 25171956]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim JH, Hwang SE, Rodríguez-Vázquez JF, Murakami G, Cho BH. Upper terminal of the inferior vena cava and development of the heart atriums: a study using human embryos. Anatomy & cell biology. 2014 Dec:47(4):236-43. doi: 10.5115/acb.2014.47.4.236. Epub 2014 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 25548721]

Shin DS, Sandstrom CK, Ingraham CR, Monroe EJ, Johnson GE. The inferior vena cava: a pictorial review of embryology, anatomy, pathology, and interventions. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2019 Jul:44(7):2511-2527. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-01988-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30937506]

Heistad DD, Armstrong ML, Amundsen S. Blood flow through vasa vasorum in arteries and veins: effects of luminal PO2. The American journal of physiology. 1986 Mar:250(3 Pt 2):H434-42 [PubMed PMID: 3953837]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakazato Y, Ohga A, Shigei T, Uematsu T. Extrinsic innervation of the canine abdominal vena cava and the origin of cholinergic vasoconstrictor nerves. The Journal of physiology. 1982 Jul:328():191-203 [PubMed PMID: 7131313]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNatsis K, Apostolidis S, Noussios G, Papathanasiou E, Kyriazidou A, Vyzas V. Duplication of the inferior vena cava: anatomy, embryology and classification proposal. Anatomical science international. 2010 Mar:85(1):56-60. doi: 10.1007/s12565-009-0036-z. Epub 2009 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 19330283]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaddock M, Robson N. The curious case of the disappearing IVC: a case report and review of the aetiology of inferior vena cava agenesis. Journal of radiology case reports. 2014 Apr:8(4):38-47. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v8i4.1572. Epub 2014 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 24967034]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoe C, Ryu RK. Anatomic and Technical Considerations: Inferior Vena Cava Filter Placement. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2016 Jun:33(2):88-92. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1581089. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27247476]

Alkhouli M, Morad M, Narins CR, Raza F, Bashir R. Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2016 Apr 11:9(7):629-43. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.12.268. Epub 2016 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 26952909]