Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Longitudinal Arch of the Foot

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Longitudinal Arch of the Foot

Introduction

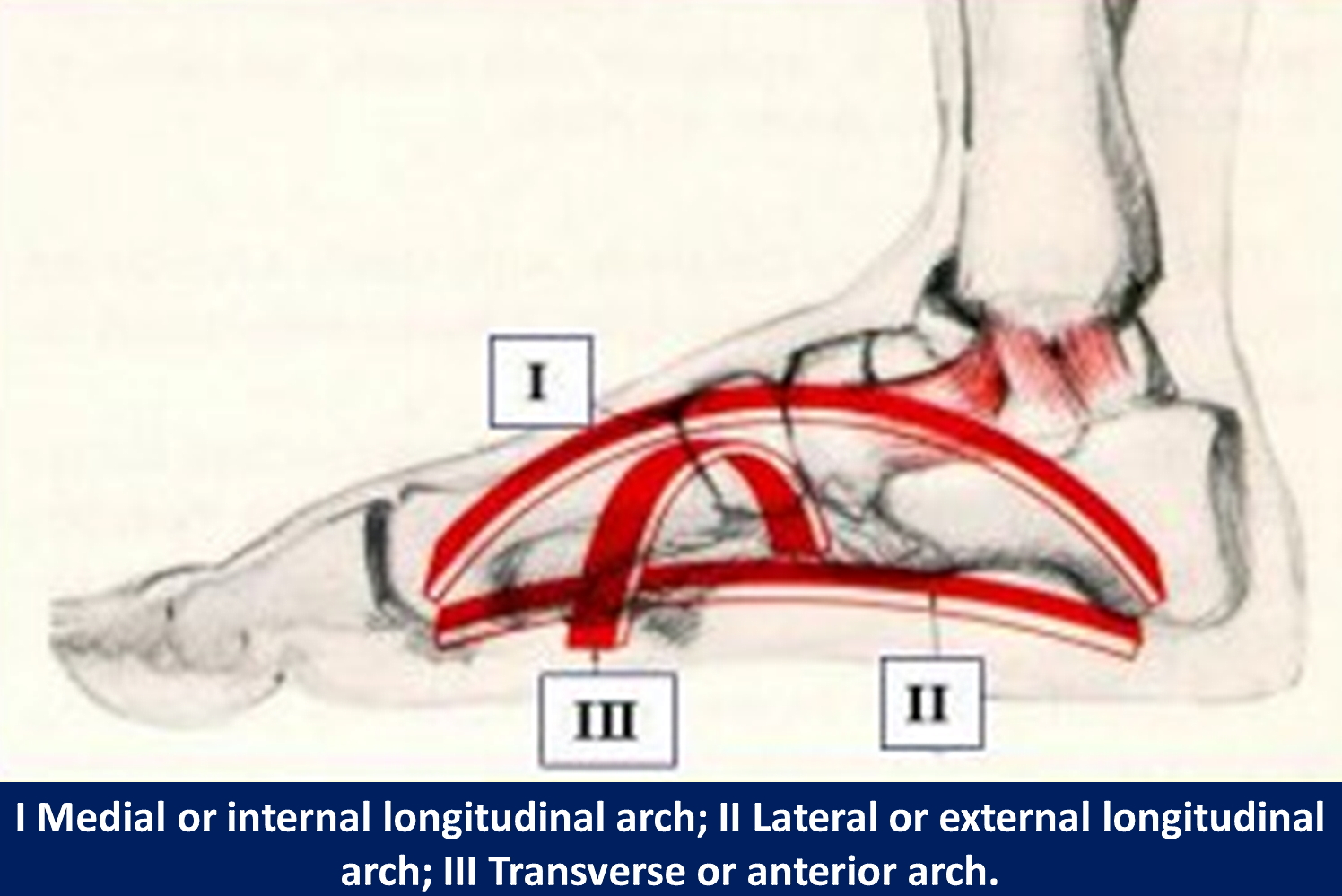

The medial longitudinal arch, the lateral longitudinal arch, and the anterior transverse arch are the three arches of the human foot (see Image. The Arches of the Foot). These arches are shaped by the metatarsal and tarsal bones and braced by tendons and ligaments of the foot. Of the two longitudinal arches, the medial arch is the highest. The bones, ligamentous structures, and plantar fascia of the arch create an elastic and adaptive base that can support the entire body.

The medial longitudinal arch of the foot allows for the proper function of the lower extremity during the gait cycle. This arch heavily relies on its muscle, innervation, and blood supply to carry out its function. Congenital anomalies or acquired trauma to any element of the medial longitudinal arch can result in mild to severe clinical consequences.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The medial longitudinal arch is formed by specific structures that allow the foot to function effectively. The medial arch is composed of the first three metatarsals, three cuneiforms, navicular, talus, and calcaneus bones of the foot. The calcaneus and talus articulate at the subtalar joint to form the hindfoot. The subtalar joint has three facets on both the calcaneus and the talus. The head of the talus is covered in convex cartilage and articulates with the navicular as the talus inferiorly and medially descends. A ball and socket joint are between the navicular and talus, with the proximal portion of the navicular forming a concave shape.

Alternately, the distal part of the navicular is convex and articulates with the proximal portions of the three cuneiform bones. The cuneiform bones articulate with the first three metatarsals. The dorsal, interosseous, and plantar components of the Lisfranc ligament connect the medial (second) cuneiform to the second metatarsal, forming the Lisfranc joint, which is important for stability.[2][3][4][5][6]

The medial longitudinal arch is formed by two pillars, the anterior and posterior pillars. The medial three metatarsal heads comprise the anterior pillar, and the posterior pillar is made up of the tuberosity of the calcaneus. The peak of the medial arch is the superior articular surface of the talus.

The medial arch garners support from the plantar calcaneonavicular ligament (spring ligament), deltoid ligament (the tibial-navicular portion, and anterior fibers), medial talocalcaneal ligament, talocalcaneal interosseous ligament, posterior tibial tendon, and plantar aponeurosis. These structures stabilize the arch and midfoot. Specifically, the spring ligament provides support for the head of the talus, and the plantar aponeurosis acts as a significant supporting structure between the two pillars of the medial arch. The spring ligament braces the joint between the talus and navicular, which is considered a weaker portion of the arch due to its exposure to overpressure. The spring ligament provides elasticity and allows the arch to retain its structure after the removal of the pressure.[2][6]

The medial longitudinal arch plays a critical role in shock absorption and propulsion of the foot while walking. To comprehend the function of the medial arch, the gait cycle must be understood. There are two phases in the gait cycle, the stance phase, and the swing phase. As the heel strikes the ground, the foot is supinated, and then it enters the stance phase. During mid-stance, the medial longitudinal arch is lengthened and flattened due to protonation of the forefoot. Elastic tendons and ligaments that become stretched during this phase store mechanical energy.

Once the medial arch reaches its maximum length, it then begins to shorten until the heel leaves the ground during terminal stance. The medial arch becomes shortened and heightened just before the toes leave the ground due to the supination of the hindfoot and elastic recoil of tissue (arch recoil). During this phase, the mechanical energy that was stored is released back to the body as power for the propulsion of the foot during the gait cycle. The anterior pillar of the medial longitudinal arch (the medial three metatarsal heads) acts as a springboard during the takeoff of the foot. The Lisfrac joint also plays a role in propulsion by allowing minor plantarflexion and dorsiflexion. While the foot is in the air, it is in the swing phase.[7][2][8][9]

Embryology

The proliferation of the mesoderm of the lateral part of the somatopleural allows for the development of limbs. Based on the third to fifth lumbar somite of the lumbar tract, the proliferations create outgrowths that develop into the hind limbs. The first development of limbs occurs during the fourth week of gestation, and the appendages continue to develop until the eighth week of gestation.

Each limb begins on the ventrolateral surface as a swelling, which is exposed to fibroblast growth factors. The swelling then transforms into a limb bud that grows in the proximal to distal direction. After 4.5 weeks of gestation, the primitive foot is visible. A few days later, the muscles and cartilaginous skeleton appear, after which toes begin to form. Skeletogenesis begins as mesenchymal condensations of mesodermal origin form structures of the skeleton. After these elements condense, ossification follows. However, endochondral ossification occurs in some tarsal bones after birth. Vascularization of the tarsal bones still arises during the fetal period.

Typically, infants are born with flat feet due to the fat pads on the plantar surfaces of their feet that protect the arches. The medial longitudinal arch appears by the time children are 5 or 6 years old. The development of the elements of the foot allows for the medial longitudinal arch to form and take shape. Developmental deformities can cause clinical consequences, as discussed later.[10][11][6]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The three main blood supplies of the foot, which arise from the popliteal artery, are the anterior tibial artery, the peroneal artery, and the posterior tibial artery. The posterior tibial artery lies between the flexor digitorum longus and flexor hallucis longus as it runs down toward the medial ankle region and plantar aspect of the hindfoot. This artery then divides into the medial and lateral plantar arteries that distally anastomose. This anastomosis forms a ring with the deep plantar arch that runs transversely. The peroneal artery supplies the posterior compartment of the foot. The anterior tibial artery supplies the anterior and dorsal regions of the foot and eventually becomes the dorsalis pedis artery when passing the extensor retinaculum. The specific arteries that supply the medial longitudinal arch of the foot are discussed in the muscles section.[2][4][11]

The venous system of the lower extremity is made up of a combination of superficial and deep veins. The deep veins run between muscles, and the superficial veins run under the skin. During every step of ambulation, these veins are emptied as the blood is pushed up the ankle and to the calf. On the anterior of the medial malleolus, the medial marginal vein ascends above the medial longitudinal arch, eventually becoming the great saphenous vein (the internal saphenous vein).[11]

Lymph from the lower extremity is drained into the common and external iliac lymph node chains. The sole has an abundance of superficial lymphatic vessels. These vessels accumulate at the medial and lateral collectors. The lymph in the medial superficial lymphatic vessels first moves to the superficial inguinal nodes and then drains into the deep inguinal nodes. While the deep lymphatic vessels and lateral superficial lymphatics vessels drain into the popliteal lymph nodes.[11]

Nerves

A majority of the innervation of the lower extremity is given rise by the sciatic nerve from the lumbosacral plexus. This nerve dives under the piriformis muscle and then moves distally. The sciatic nerve branches into the common fibular nerve and tibial nerve at the distal one-third of the femur. As it moves distally, the tibial nerve branches into the medial calcaneal, medial sural cutaneous, medial plantar, and lateral plantar nerves. Also, the common peroneal nerve divides into the deep peroneal nerve and the superficial peroneal nerve.

The deep peroneal nerve provides the motor function for the muscles that dorsiflex the foot, and the superficial peroneal nerve accepts sensory information through the cutaneous branches. The following section will discuss specific innervations of the muscles of the medial longitudinal arch.[11][12][13]

Muscles

The following muscles of the foot provide support and allow for the effective function of the medial longitudinal arch. Research shows the intrinsic plantar muscles of the foot play a role in the stance phase of the gait cycle by assisting in foot ground force transmission and shock absorption. During the early and mid-stance phases, these muscles lengthen and dissipate mechanical energy. In the late stance phase, they produce mechanical energy to assist and stabilize the foot during propulsion.[14][15][16][9]

The abductor hallucis is in the first layer of the intrinsic muscles. It originates in the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts at the base of the great toe, allowing the great toe to abduct. Its blood supply comes from the medial plantar artery, and innervation is by the medial plantar nerve.[11][16]

The flexor digitorum brevis muscle is also in the 1st layer of intrinsic plantar muscles. This muscle originates in the calcaneal tuberosity and inserts on toes two through five at the middle phalanx, allowing those digits to flex. The flexor hallucis brevis muscle flexes the great toe. It originates on the lateral cuneiform and cuboid bones and inserts on the proximal phalanx of the great toe. Both muscles have the same blood supply and innervation as the abductor hallucis (medial plantar artery and medial plantar nerve).[11][6][16]

The three plantar interossei muscles originate at the medial metatarsal of the third through fifth digits and adduct the toes. They insert on the proximal phalanges. The interossei muscles are supplied by the plantar metatarsal artery and innervated by the lateral plantar nerve.[11]

The next set of muscles involved in the medial longitudinal arch is those that are grouped based on their actions in the foot and ankle. The tibialis posterior originates in the upper two-thirds of the tibia’s medial posterior surface. The tendon then inserts on the plantar surfaces of the second, third, and fourth metatarsals (the deep slip) and the tuberosity of the navicular (the superficial slip). It is supplied by the posterior tibial, peroneal, and sural arteries and innervated by the tibial nerve. Although the important action of the tibialis posterior is to invert the foot, it also helps in the supination, plantar flexion, and adduction of the foot. Thereby the actions of this muscle provide the maintenance of the height of the arch. Damage to the tibialis posterior could potentially cause the arch to collapse, leading to significant issues. The tibialis posterior also has a long elastic tendon. The recoil and stretch of this tendon absorb and dissipate mechanical energy at the hindfoot.[11][16][9]

The tibialis anterior muscle originates on the lateral condyle of the tibia and the upper half of the lateral tibia. The insertion is on the medial cuneiform at the medial and plantar surfaces and base of the first metatarsal. This muscle’s actions include dorsiflexing the ankle and inverting the hindfoot. It receives supply via the anterior tibial artery and innervation from the deep peroneal nerve.[11][16]

The flexor hallucis longus muscle originates on the posterior fibula at the inferior two-thirds and inserts at the base of the great toe’s distal phalanx on the plantar surface. This muscle mainly flexes the great toe. Its blood supply derives from the posterior tibial artery, and innervation is from the tibial nerve. The flexor hallucis longus acts as a bowstring for the medial longitudinal arch.[11][16][6]

The flexor digitorum longus muscle originates on the posterior distal tibia and splits into four tendons. These tendons insert on the base of the distal phalanges 2 through 5 on the plantar surface. The tendons allow for the flexion of these digits. The posterior tibial artery supplies this muscle, and its innervation is by the tibial nerve.[11][16]

The peroneus longus (fibular longus) originates at the head of the fibula and upper fibular shaft and inserts on the lateral base of the first metatarsal and the medial cuneiform’s posterolateral portion. It plantar flexes the ankle and everts the foot. Vascular supply is by the anterior tibial artery and innervated by the superficial peroneal nerve. This muscle also forms a sling with the tibialis anterior muscle.[11][16]

The peroneus brevis (fibular brevis) originates at the inferior lateral portion of the fibula and then inserts on the fifth metatarsal’s styloid process to plantarflex the ankle and evert the foot. It receives vascular supply from the peroneal artery and innervation via the superficial peroneal nerve.[11][16]

Physiologic Variants

Physiologic variants of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot include pes planus (flat foot) and pes cavus (high arch). Both these conditions are considered variations of foot alignment and can be categorized as congenital or acquired. Pes planus and pes cavus are discussed in the following sections.[2]

Surgical Considerations

Pes Planus

For children, surgery is only a consideration in cases of rigid pes planus, which is rare. Rigid pes planus occurs in association with congenital virtual talus, accessory navicular bone, tarsal coalition, or another congenital hindfoot pathology. In adults, surgery is added to the treatment plan once other therapies have been exhausted. Pes planus is a topic for further discussion in the following section.[6]

Pes Cavus

A possible treatment for severe cases of pes cavus includes surgery. Operative intervention may be important as deformities continue to worsen and muscles become imbalanced. Surgery is recommended before there are signs of degenerating joints and fixed deformities. Surgical options include in-phase or out-of-phase tendon transfers. Operative treatment plans may also be necessary to correct other pathologies that are associated with subtle pes cavus. More information about pes cavus appears in the next section.[17]

Plantar Fasciitis

Surgery is the last option for treatment and should only merit consideration if the condition worsens or becomes chronic and other therapies have not been successful. A discussion of plantar fasciitis appears in the next section.[12]

Clinical Significance

Defects or deformities of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot can lead to clinical consequences. One such example is pes planus, also known as pes valgus or flat foot. This condition demonstrates the loss of the medial longitudinal and can be congenital or acquired. As described before, most infants are born with flat feet and develop normal arches by the age of 6. The most common cause of congenital pes planus in children is flexible pes planus; this is when the arch appears normal without weight-bearing and disappears with weight-bearing.

The collapse of the arch in children has also correlated with obesity. Posterior tibial tendon dysfunction is the most common cause of acquired pes cavus. The classical presentation of this is a woman above the age of 40 with diabetes and obesity. Other structures of the medial longitudinal arch that can contribute to pes planus are the laxity of the plantar fascia, spring ligament, or other plantar ligaments. Any type of trauma or injury to the midfoot or hindfoot can also lead to pes planus. Although it is usually asymptomatic, pes planus includes pain in the back, hip, knee, lower leg, heel, and midfoot. Patients also may present with a history of frequent ankle sprains due to overpronation while ambulating.[6]

Another condition that affects the medial longitudinal arch is pes cavus, also known as clawfoot. The most prominent feature of pes cavus is the elevation of the medial longitudinal arch of the foot. A clawfoot usually results from a deformity of the forefoot or the hindfoot, or a combination of both. In pes cavus, the peroneus longus and posterior tibialis are stronger and overpower the peroneus brevis, tibialis anterior, and intrinsic foot muscles. The peroneus longus commonly contractures in this condition, causing the plantarflexion of the first ray. The higher arch in this condition decreases the foot’s ability to absorb shock and puts excess pressure on the heel and the ball of the foot.

Congenital (hereditary) pes cavus is typically bilateral. The four major causes of this condition are neurological issues, trauma, untreated clubfoot, or it could be idiopathic. Symptoms of pes cavus include foot, ankle, and knee pain, as well as frequent ankle sprains. Patients may also notice that their shoes no longer fit or start wearing out quickly. There may also be a family history of similar foot deformities. A physical examination may show metatarsals that are tender to palpation. Also, an important sign of pes cavus is when the heel pad of the foot is visualized from the front when the patient is standing with both feet pointing forward (“peek-a-boo” heel).[18][17]

Both pes planus and pes cavus can result in a condition known as plantar fasciitis. The plantar fascia is a major supporting element of the medial longitudinal arch that also plays a role in shock absorption. Plantar fasciitis is an irritation of the plantar fascia resulting in degeneration. Although it is due to many factors, the most common cause is an overuse injury due to repetitive strain on the foot. The plantar fascia can develop micro-tears associated with weight-bearing and standing upright. As a predisposing factor, pes planus results in a strain at the medial calcaneal tuberosity and the adjacent perifascial structures (the origins of the plantar fascia).

In pes cavus, the foot does not properly absorb shock or evert; therefore, this also causes increased strain on the heel and can cause plantar fasciitis. Patients typically present with a gradual onset of sharp pain in the heel, which is worst in the morning after arising from bed. Pain lessens during the beginning of walking or other physical activities and then increases during the day. Symptoms also become aggravated by standing for an extended amount of time. During a physical exam, pain is noted when palpating the plantar medial calcaneal tubercle and during passive dorsiflexion of the foot and toes.[19]

Other Issues

During the postural assessment of a person standing upright, it is possible to evaluate the medial longitudinal arch of the foot under load quickly and practically. It is sufficient to draw the imaginary line of Feiss to determine if there is a physiological medial longitudinal arch. This line is obtained by joining the medial malleolus and the first metacarpal-phalangeal joint; once this line has been drawn, it is sufficient to observe whether the scaphoid tuberosity is crossed by this line and in this case, the plantar arch will be physiological. If, on the other hand, the scaphoid tuberosity is above this line, it means that the foot is flat/supinated; if the scaphoid tuberosity is below Feiss's line, it means that the foot is flat/pronated.

In obese young/adult subjects, there is an inverse relationship between the thickness of the fascial tissue at the level of the medial arch and the lowering of the latter.[20]

In subjects with a decrease in the medial longitudinal arch, there is an increase in the thickness of the abductor hallucis muscle; this adaptation could, in the long run, create postural alterations.[21]

Media

References

Gwani AS, Asari MA, Mohd Ismail ZI. How the three arches of the foot intercorrelate. Folia morphologica. 2017:76(4):682-688. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2017.0049. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28553850]

Ficke J, Byerly DW. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536304]

Russell TG, Byerly DW. Talus Fracture. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969509]

MacGregor R, Byerly DW. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Foot Bones. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491379]

Brockett CL, Chapman GJ. Biomechanics of the ankle. Orthopaedics and trauma. 2016 Jun:30(3):232-238 [PubMed PMID: 27594929]

Raj MA, Tafti D, Kiel J. Pes Planus. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613553]

Kayano J. Dynamic function of medial foot arch. Nihon Seikeigeka Gakkai zasshi. 1986 Nov:60(11):1147-56 [PubMed PMID: 3819541]

Han K,Bae K,Levine N,Yang J,Lee JS, Biomechanical Effect of Foot Orthoses on Rearfoot Motions and Joint Moment Parameters in Patients with Flexible Flatfoot. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2019 Aug 8; [PubMed PMID: 31393860]

Kelly LA, Cresswell AG, Farris DJ. The energetic behaviour of the human foot across a range of running speeds. Scientific reports. 2018 Jul 12:8(1):10576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28946-1. Epub 2018 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 30002498]

Marín-Llera JC, Garciadiego-Cázares D, Chimal-Monroy J. Understanding the Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms That Control Early Cell Fate Decisions During Appendicular Skeletogenesis. Frontiers in genetics. 2019:10():977. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00977. Epub 2019 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 31681419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCard RK, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Muscles. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969527]

Yablon CM,Hammer MR,Morag Y,Brandon CJ,Fessell DP,Jacobson JA, US of the Peripheral Nerves of the Lower Extremity: A Landmark Approach. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 26871986]

Taber KH, Duncan G, Chiou-Tan F, Patni P, Hayman LA. Sectional neuroanatomy of the lower limb II: leg and foot. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 2001 Sep-Oct:25(5):823-6 [PubMed PMID: 11584247]

Okamura K, Kanai S, Hasegawa M, Otsuka A, Oki S. The effect of additional activation of the plantar intrinsic foot muscles on foot dynamics during gait. Foot (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2018 Mar:34():1-5. doi: 10.1016/j.foot.2017.08.002. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 29175714]

Nakayama Y, Tashiro Y, Suzuki Y, Kajiwara Y, Zeidan H, Kawagoe M, Yokota Y, Sonoda T, Shimoura K, Tatsumi M, Nakai K, Nishida Y, Bito T, Yoshimi S, Aoyama T. Relationship between transverse arch height and foot muscles evaluated by ultrasound imaging device. Journal of physical therapy science. 2018 Apr:30(4):630-635. doi: 10.1589/jpts.30.630. Epub 2018 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 29706721]

Angin S,Crofts G,Mickle KJ,Nester CJ, Ultrasound evaluation of foot muscles and plantar fascia in pes planus. Gait [PubMed PMID: 24630465]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSeaman TJ, Ball TA. Pes Cavus. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310476]

Manoli A 2nd, Smith DG, Hansen ST Jr. Scarred muscle excision for the treatment of established ischemic contracture of the lower extremity. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1993 Jul:(292):309-14 [PubMed PMID: 8519125]

Buchanan BK, Sina RE, Kushner D. Plantar Fasciitis. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613727]

Park SY,Park DJ, Comparison of Foot Structure, Function, Plantar Pressure and Balance Ability According to the Body Mass Index of Young Adults. Osong public health and research perspectives. 2019 Apr [PubMed PMID: 31065537]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaş S, Ünlüer NÖ, Korkusuz F. Morphological and mechanical properties of plantar fascia and intrinsic foot muscles in individuals with and without flat foot. Journal of orthopaedic surgery (Hong Kong). 2018 May-Aug:26(3):2309499018802482. doi: 10.1177/2309499018802482. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30270752]