Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Female External Genitalia

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Female External Genitalia

Introduction

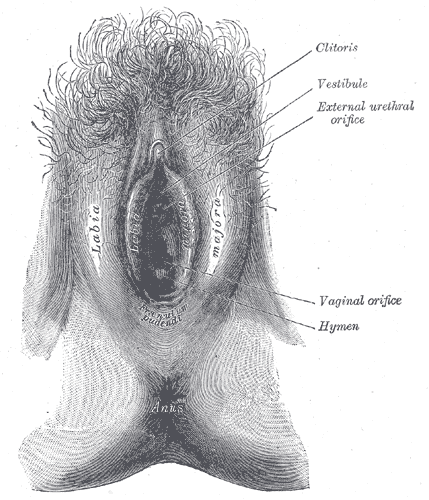

The female external genitalia is fascinating due to the fact it is made up of both urinary tract and reproductive structures. These structures collectively fall under the term vulva. The definition of "vulva" is covering or wrapping. From the exterior observation of the female external genitalia, it does appear to be covered or wrapped by skin folds. These skin folds are called the labia majora and labia minora. Both labia majora and labia minora are part of the vulva. The components of the entire vulva are the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, urethra, vulva vestibule, vestibular bulbs, Bartholin's glands, Skene's glands, and vaginal opening. The external female genitalia serves the purposes of reproduction and urination.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Vulva

The vulva is the global term that describes all of the structures that make the female external genitalia. The components of the vulva are the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, vestibular bulbs, vulva vestibule, Bartholin's glands, Skene's glands, urethra, and vaginal opening.

Mons Pubis

The mons pubis is a tissue mound made up of fat located directly anterior to the pubic bones. This mound of tissue is prominent in females and is usually covered in pubic hair. The mons pubis functions as a source of cushioning during sexual intercourse. The mons pubis also contains sebaceous glands that secrete pheromones to induce sexual attraction.

Labia Majora

The word "labia majora" is defined as the larger lips. The labia majora are a prominent pair of cutaneous skin folds that will form the lateral longitudinal borders of the vulval clefts. The labia majora forms the folds that cover the labia minora, clitoris, vulva vestibule, vestibular bulbs, Bartholin's glands, Skene's glands, urethra, and the vaginal opening. The anterior part of the labia majora folds comes together to form the anterior labial commissure directly beneath the mons pubis. While the posterior part of the labia majora comes together to form the posterior labial commissure. The labia majora engorges with blood and appears edematous during sexual arousal.

Labia Minora

The "labia minora" is defined as the smaller lips. The labia minor are a pair of small cutaneous folds that begins at the clitoris and extends downward. The anterior folds of the labia minora encircle the clitoris forming the clitoral hood and the frenulum of the clitoris. Then the labia minor descends obliquely and downward forming the borders of the vulva vestibule. Eventually, posterior ends of the labia minora terminate as they become linked together by a skin fold called the frenulum of the labia minora. The labia minora will encircle the vulva vestibule and terminating between the labia majora and the vulva vestibule. With sexual arousal, the labia minora will become engorged with blood and appear edematous.

Clitoris

The clitoris (which is homologous to the glans penis in males) is a sex organ in females that functions as a sensory organ. The clitoris can be divided into the glans clitoris and the body of the clitoris. The underlying tissue that makes the clitoris is the corpus cavernous. The corpus cavernous is a type of erectile tissue that merges together and protrudes to the exterior of the vulva as the glans clitoris. While proximally, the two separate ends of the tissue will form the crus of the clitoris (legs of the clitoris) and the body of the clitoris. The glans clitoris is the only visible part of the clitoris. The glans clitoris is highly innervated by nerves and perfused by many blood vessels. It is estimated that glans clitoris is innervated by roughly eight thousand nerve endings. Since the glans clitoris is so highly innervated, it becomes erected and engorged with blood during sexual arousal and stimulation.

Vestibular bulbs

The vestibular bulbs (homologous to the bulb of the penis in males) are structures formed from corpus spongiosum tissue. This is a type of erectile tissue closely related to the clitoris. The vestibule bulbs are two bulbs of erectile tissue that starts close to the inferior side of the body of the clitoris. The vestibular bulbs then extend towards the urethra and vagina on the medal edge of the crus of the clitoris. Eventually, the vestibular bulbs will split and surround the lateral border of the urethra and vaginal. The vestibular bulbs are believed to function closely with the clitoris. During sexual arousal, the vestibular bulbs will become engorged with blood. The engorgement of blood then exerts pressure onto the corpus cavernosum of the clitoris and the crus of the clitoris. This exertion of pressure onto the clitoris is believed to induce a pleasant sensation during sexual arousal.

Vulva Vestibule

The area between the labia minora is the vulva vestibule. This is a smooth surface that begins superiorly just below the clitoris and ends inferiorly at the posterior commissure of the labia minora. The vulva vestibule contains the opening to the urethra and the vaginal opening. The borders of the vulva vestibule are formed from the edge of the labia minora. There is a demarcation between the vulva vestibule and the labia minora called Hart's lines. Hart's lines identify the change from the vulva vestibule to the labia minora. This change of skin appearance is visible by the smoother transitional skin appearance of the vulva vestibule to the vulvar appearance of the labia minora.

Bartholin's Glands

The Bartholin's glands also known as the greater vestibular glands (homologous to the bulbourethral glands in males) are two pea-sized glands located slightly lateral and posterior to the vagina opening. These two glands function to secrete a mucus-like substance into the vagina and within the borders of the labia minora. This mucus functions as a lubricant to decrease friction during intercourse and a moisturizer for the vulva.

Skene's Glands

The Skene's glands, which are also known as the lesser vestibular glands (homologous to the prostate glands in males), are two glands located on either side of the urethra. These glands are believed to secrete a substance to lubricate the urethra opening. This substance is also believed to act as an antimicrobial. This antimicrobial is used to prevent urinary tract infections. The function of Skene's gland is not fully understood but is believed to be the source of female ejaculation during sexual arousal.

Urethra

The urethra is an extension of a tube from the bladder to the outside of the body. The purpose of the urethra is for the excretion of urine. The urethra in females opens within the vulva vestibule located inferior to the clitoris, but superior to the vagina opening.

Vagina

The vagina is an elastic, muscular tube connected to the cervix proximally and extends to the external surface through the vulva vestibule. The distal opening of the vagina is usually partially covered by a membrane called the hymen. The vaginal opening is located posterior to the urethra opening. The function of the vagina is for sexual intercourse and childbirth. During sexual intercourse, the vagina acts as a reservoir for semen to collect before the sperm ascending into the cervix to travel towards the uterus and fallopian tubes. Also, the vagina also acts as an outflow tract for menses.

Embryology

During embryology, the fetus starts with undifferentiated gonads. The gonads will either develop into testes or ovaries. The gonads form into testes due to the influences from the SRY gene, but without the SRY gene, the gonads will default into ovaries. The ovaries are the dominant organ in females that make and secrete sex hormones for females. The theca cells and granulosa cells within the ovaries produce sex hormones for females. The theca cells make androgens, and the granulosa cells take the androgen and convert it into estrogen. Estrogen is the dominant influence on the development of the female external genitalia.

The female external genitalia develops from many default structures such as the genital tubercle, urogenital sinus, urogenital folds, and the labioscrotal swellings/folds. The genital tubercles will differentiate into the glans clitoris and the vestibular bulbs in the females while the equivalent in males is the glans penis and the corpus cavernosum and spongiosum. The urogenital sinus will develop into the Bartholin's glands, Skene's glands, and the urethra in females. The urogenital sinus forms the bulbourethral glands and the prostate glands in males. The labia majora originates from the labioscrotal folds in females while it forms the scrotum in males. Lastly, the urogenital folds form the labia minora in females and it forms the ventral shaft of the penis in males. The reason that these default structures differentiate into female external genitalia instead of males' is due to the influence of estrogen. If these structures were under the influence of testosterone, they would develop into male external genitalia.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial

The internal pudendal artery perfuses the majority of the external female genitalia. The internal pudendal artery is a branch of the internal iliac artery. Once the pudendal artery branches from the internal iliac artery, it descends towards the external genitalia. The internal pudendal artery will then become the dominant blood supply to the female external genitalia. The labia majora also received blood from the superficial external pudendal artery. The superficial external pudendal artery is a tributary of the femoral artery.

Venous

The venous drainage of the external female genitalia is via the external and internal pudendal veins. The external pudendal vein will drain towards the great saphenous vein. The saphenous vein will drain back into the femoral vein. As the femoral vein ascends pass the inguinal ligament, it becomes the external iliac vein. While the internal pudendal vein drains back into the internal iliac vein. Both the external and internal iliac veins will ascend and merge to form the common iliac veins. The common iliac veins from both sides of the body will ascend to about the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. At the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra, the common iliac veins merge to drain venous blood back into the inferior vena cava. The inferior vena cava will ascend towards the heart. Upon reaching the heart, the inferior vena cava drains its venous blood back into the right atrium.

Lymphatic

The lymphatic drainage of the external female genitalia drains toward the superficial inguinal lymph nodes except for the clitoris. The lymph from the clitoris will drain towards the deep inguinal lymph nodes. The lymph from the superficial and deep inguinal lymph nodes will ascend toward the common iliac lymph nodes. All of this lymph will ascend towards the distant part of the thoracic duct called the cisterna chyli. Once at the cisterna chyli, the lymph will drain into the thoracic duct and ascends toward the angle formed from the left subclavian vein and the left internal jugular vein. All of the lymph from the external female genitalia will drain back into the central circulation via the thoracic duct.[1]

Nerves

The motor, sensory, and sympathetic nerve innervation of the external female genitalia originate from the pudendal nerve. The pudendal nerve is made up of the second, third, and fourth sacral spinal roots. The pudendal nerve will enter the pelvis via the lesser sciatic foramen. Once pass the lesser sciatic foramen, the pudendal nerve will travel in the pudendal canal towards the ischial spines. The pudendal nerve then encircles the ischial spine and form branches that innervate the perineum and the external genitalia. The pudendal nerve will branch into three main branches: the dorsal nerve for the clitoris, the perineal nerve for the external genitalia, and the inferior rectal nerve. The dorsal nerve of the clitoris provides the afferent part for clitoral erection. In addition to the dorsal nerve of the clitoris, the clitoris's cavernous tissue is innervated by the cavernous nerves from the uterovaginal plexus. As for the perineal nerve branch, it will provide sensory to the external genitalia via the posterior labial nerves. The perineal nerve also gives off a branch that provides motor innervation to the external urethral sphincter. The perineal nerve also gives off muscular nerve branches that innervate the muscles of the perineum. These muscles are the bulbospongiosus, ischiocavernosus, levator ani (iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus, and puborectalis muscle), and pubovaginalis muscles. Lastly, the inferior rectal nerve will provide innervation to the perianal skin and the external anal sphincter. The labia majora also received addition innervation from the anterior labial nerves (branches of the ilioinguinal nerve). The mons pubis also receives additional sensory innervation from the genitofemoral nerve.

It is common to anesthetize the pudendal nerve during childbirth. The landmark for the injection of anesthetic is the ischial spines. The physician will palpate for the ischial spine from the inside of the vaginal canal. Then the anesthetic will be injected towards the ischial spine to block the sensory territory of the pudendal nerve; this may be done to decrease pain sensation during child delivery, to numb the perineum before an episiotomy, or for the relief of chronic pelvic pain syndromes.

Muscles

Many muscles act on the external female genitalia either by forming and supporting the perineum or the pelvic floor.

- Bulbospongiosus muscle

- Ischiocavernosus muscle

- Deep transverse perineal muscle

- Superficial transverse perineal muscle

- Levator ani muscle

- Iliococcygeus muscle

- Pubococcygeus muscle

- Puborectalis muscle

- Pubovaginalis muscle

- Coccygeus muscle

- Perineal body

- External anal sphincter

- External urethral sphincter

Physiologic Variants

The female external genitalia varies greatly. The shape, size, and color of the mons pubis, clitoris, labia majora, labia minora, and the vagina orifice are different from female to female. The reason for the variations is due to the amount of estrogen influence during development. If there is more estrogen, these structures tend to be larger and thicker. While the lack of estrogen can lead to the external genitalia being thinner and smaller. For instance, the mons pubis is heavy influenced by estrogen. The mons pubis is larger in females with more estrogen as compared to a less prominent mons pubis in females with less estrogen. As for the structure with the most variations in the female external genitalia, is the labia majora and the labia minora. The labia majora and labia minora tend to be the structures that vary greatly in size, color, and length when comparing females. Some females have more prominent labial folds visually. In some females, the clitoris and the clitoris hood may be larger and more prominent visually. While many of these structures can vary greatly. In general, the functionality of these structures is unchanged.[2]

These variations in the female external genitalia can be due to aging and the lack of estrogen also. During menopause, women start to have a decrease in the production of estrogen. This decrease in estrogen causes the female external genitalia to atrophy.[3][4]

Surgical Considerations

In surgery, knowledge of the anatomy of the female external genitalia is crucial when it comes to repairing, reconstructing, or preventing undesirable defects to the genitals. Some common procedures done to the female external genitalia are episiotomy, labioplasty, and vaginoplasty.

Episiotomy

In episiotomies, the vaginal opening is enlarged by an incision that is done either midline or laterally during delivery of a child that risks tearing and damaging the vaginal opening. If the incision is performed midline, the perineal body will be the target of the incision. While the lateral episiotomy targets the transverse perineal muscle. The reason for performing episiotomies is that an incision can be easily repaired and decrease healing time, in contrast with a torn vaginal opening that could potentially involve the perineum muscles and the rectum. The repair of a torn vaginal opening due to a large child delivery has a longer healing time. Episiotomies are done as procedures to aid in vaginal delivery of large offsprings and the prevention of vaginal tearing into other perineum structures.[5][6]

Labioplasty

Labioplasty is a surgical procedure with emphasize on altering the size and shape of the labia majora and labia minora. Indications for labioplasty include multiple reasons, such as congenital defects, aging, cancers, and cosmetics. The focus of this procedure is to create a more desirable appearance of the labial folds.[7][8][9]

Vaginoplasty

Vaginoplasty is a surgical procedure used to reconstruct or construct the vagina. Vaginoplasties are necessary for several reasons, such as pelvic organ prolapse, congenital defects, neoplasms, sex reassignments, and cosmetics. The goal of the vaginoplasty is to surgically make a vagina that is desirable for the patient.[9][10]

Clinical Significance

The anatomy of the female external genitalia is vital in clinical settings. The importance of this anatomy comes to the fore with the diagnosis of various diseases and lesions that affect the female genitals. Also, the knowledge of the female genitals is important when it comes to performing procedures involving the vulva.

Urinary Tract

Foley Catheter: One common procedure that is routinely due in healthcare is the catheterization of the female urethra. This procedure involves the introduction of a flexible tube into the urethra and securing it in place with a saline-filled balloon. This procedure is done to assist in the excretion of urine from the bladder. This method can be used to collect urine for surveillance monitoring of the amount of urine produced or to collect urine used for the analysis of other pathologies.

Urinary Tract Infection: One common pathology that involves the urethra is a urinary tract infection (UTI). In urinary tract infections, the patient classically complains of dysuria, increased urination, foul-smelling urination, and cloudy urine. This condition commonly affects females due to their urethrae are shorter than males' urethrae. The short urethra in females allows the bacteria to ascend the urethra more readily, and the anatomical location of the urethra, vagina, and anus allows for cross-contamination between the vaginal and anal bacteria into the urethra. The most common bacteriologic etiology of urinary tract infections is gram-negative rods, with the most common bacteria being Escherichia coli.

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Haemophilus ducreyi: Infection of the vulva region may manifest as a rash or ulcer-like lesion. One bacteria that present as an ulcerative lesion is Haemophilus ducreyi (chancroid). This bacteria causes painful ulcerative lesions described as having irregular, jagged borders with exudative drainage. This condition also presents with inguinal adenopathy. The treatment for this infection is third-generation cephalosporins, macrolides, or fluoroquinolones.

Klebsiella granulomatis: Infection with the bacteria Klebsiella granulomatis causes lesions similar to Haemophilus ducreyi. But the main difference is that these lesions appear as a painless, beefy red ulcer that bleeds with touching, and it lacks inguinal adenopathy. Treatment of this condition involves macrolides, tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, or Bactrim.

Chlamydia trachomatis: Infection with chlamydia is a common, sexually transmitted infection. In most individuals, this infection is asymptomatic, but some individuals may present with cervicitis, urethritis, and vaginal discharge. The fear complication of this infection in females is pelvic inflammatory disease and perihepatitis. Interestingly, chlamydia is commonly coinfected with Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Since these two bacteria commonly cause infection together, the treatment is tetracyclines or macrolides for chlamydia and third-generation cephalosporins for gonorrhea.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae: Infection with Neisseria gonorrhoea manifest similar to chlamydia that it is commonly asymptomatic. But the infection may present with urethritis, cervicitis, and creamy purulent vaginal discharge. The fear complication of this infection is pelvic inflammatory disease and perihepatitis. Treatment for gonorrhea is the same as chlamydia since the two bacteria commonly cause coinfections. The treatment is tetracyclines or macrolides for chlamydia and third-generation cephalosporins for gonorrhea.

Treponema pallidum: Syphilis infections result from Treponema pallidum. This infection usually manifests as a painless chancre in the primary stage. If the disease is left untreated, it will progress to the secondary stage. In the secondary stage, it manifests as fever, widespread maculopapular skin rashes involving the palms and soles, widespread lymphadenopathy (epitrochlear node is pathognomic), and genital lesions similar to genital warts (condylomata lata- has a rounder surface when compared with condylomata acuminata). If there is still no treatment during the secondary stage, the infection will progress into the tertiary stage. The tertiary stage causes necrotic lesions called Gummas, neurological symptoms such as tabes dorsalis, Argyll Robertson pupils, and general paresis, cardiac symptoms such as aortitis. The treatment of syphilis is with the use of penicillin.

Herpes Simplex Virus 1&2: Genital herpes is due to the infection from Herpes simplex virus 1&2 (HSV1&2), with HSV2 being the most common in the genital region. This infection manifest as episodes of painful vesicular lesions. Constitutional symptoms may accompany these lesions. Unfortunately, this condition is chronic and incurable. But infected patients can take acyclovir to decrease flare-ups and decrease the viral shedding load.

Human Papillomavirus: Genital wart is a condition that manifests as cauliflower-like lesions in the genital region called condylomata acuminata. This lesion is due to the infection from the human papillomavirus (HPV). The human papillomavirus comes in many viral strains, but HPV6 and HPV11 strains are the strains that cause genital warts. The defining feature of genital warts is koilocytes on histology. Fortunately, this condition is usually self-limiting and will resolve on its own. In some individuals, the virus is not cleared appropriately by the immune system, which results in chronic genital warts and may progress to cancer.

Human immunodeficiency virus: Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is an infection that can be due to unprotected intercourse or the transfer of blood-borne products. This infection is usually asymptomatic for a few years, but it slowly destroys and decreases the number of T helper lymphocytes. Once the T helper lymphocytes decrease lower than 200 cells/mm3, the disease progresses into Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). AIDS presents as many different diseases, but the most common presentation is infection with opportunistic infections. Unfortunately, there is no curable treatment for HIV-AIDS. There are many maintenance medications to prolong the progression of the disease.

Hepatitis B and C: Hepatitis is inflammation of the liver. Hepatitis B and C are viruses potentially transmitted during intercourse. Most individuals are asymptomatic. The main concern for this infection is the progression to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatitis B is preventable with vaccination, but there is no vaccination for hepatitis C. The only prevention for hepatitis C is barrier protection during intercourse and avoiding blood-borne products from infected individuals. There are treatment options for hepatitis B and C, but they are usually maintenance medications that slow the progression of the disease. Unfortunately, no real cure exists for these two diseases.

Vulvar Pathology

Bartholin cyst and abscess: Bartholin's glands are glands that produce secretions to lubricate the vulva and vagina. This gland can become obstructed and form a cyst containing the buildup of lubricant. If the cyst becomes infected, it then progresses to become an abscess. This condition tends to affect females of reproductive age. Bartholin cyst/abscess presents as a swelling located posterolateral to the vaginal orifice. This infection may result from infection with Escherichia coli, Chlamydia trachomatis, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Lichen sclerosus: The vulva region is a sensitive region that may be prone to irritations. In lichen sclerosus, the vulva is under chronic irritation resulting in itching. This itching causes the patient to scratch, and over time the trauma from scratching will cause the vulvar skin to undergo lichenification (thickening). Lichen sclerosus is the thinning of the epidermis and thickening/fibrosis of the dermis. It appears as white parchment paper like lesions. This condition affects prepubertal and postmenopausal females with an increased risk of vulvar cancer. The treatment is topical steroids.

Lichen simplex chronicus: In lichen simplex chronicus, the vulvar region undergoes hyperplasia of the epithelium. This condition presents as a thick, leathery vulvar skin due to chronic scratching and rubbing. This condition is not associated with an increased risk of cancer.

Imperforate hymen: In pubertal females that reach the age of menarche, but do not have menses is called primary amenorrhea. One cause of primary amenorrhea is imperforate hymen. These females present with monthly pain and pressure in the lower abdomen, but not excretion of mense. On physical examination, there will be a blue, brown round bulging mass protruding from the vagina. The mass protruding from the vagina is a collection of the menstrual products getting trapped due to an imperforate hymen. The treatment for this condition is incision and drainage of the mass.

Neoplastic

Vulvar carcinoma: Cancer of the vulvar region is rare. The most common cancer involving the vulvar region is squamous cell carcinoma. This malignancy could be due to a transformation of leukoplakia or due to the infection from HPV16 or HPV18. Lichen sclerosus can also progress to vulvar cancer. A biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Extramammary Paget Disease: Padget disease of the vulva is usually a type of carcinoma in situ. This condition presents as scaling plaques, crusting, pruritus, ulcers, and erythema. But there is no risk for underlying malignancies.

Other Issues

Since the development of the female external genitalia is dependent on hormones. The vulva region can be affected by endocrine-related conditions. The endocrine system is the system that influences/controls the secretions of hormones. If there is a defect in the endocrine system, males can present with female external genitalia. One example of males with female external genitalia is in "androgen insensitivity syndrome" (AIS). In AIS, androgen receptors are insensitive to androgens. The insensitivity of these receptors makes them unresponsive to testosterone and androgens. Then the external genitals will default into developing into female external genitals.[11] While females can undergo virilization if there is an excess of androgens such as in "congenital adrenal hyperplasia" (CAH). In CAH, there is a defect in the adrenal production of aldosterone and cortisol, which results in all the aldosterone and cortisol precursors getting shunted to the production of androgens in the adrenal glands. The excess androgens affect the female external genitalia by making them more masculine. The clitoris becomes larger (clitoromegaly) and the fusion of the labia majora. The fusion of the labia majora will make it appear more scrotal-like.[12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

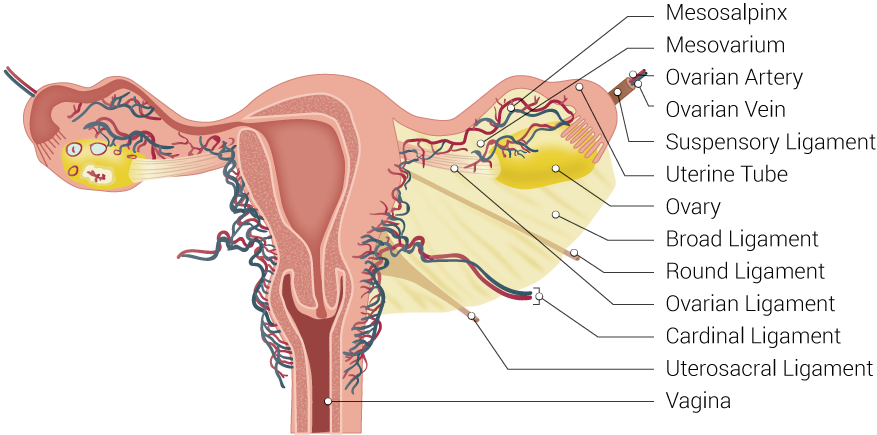

Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments. Anatomical structures surrounding the uterus and fallopian or uterine tubes, including the mesosalpinx, mesovarium, ovarian artery, ovarian vein, suspensory ligament, uterine tube, ovary, broad ligament, round ligament, ovarian ligament, cardinal ligament, uterosacral ligament, and vagina.

Contributed by B Palmer

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Curry SL, Wharton JT, Rutledge F. Positive lymph nodes in vulvar squamous carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology. 1980 Feb:9(1):63-7 [PubMed PMID: 7353802]

McQuillan SK, Jayasinghe Y, Grover SR. Audit of referrals for concern regarding labial appearance at the Royal Children's Hospital: 2000-2012. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2018 Apr:54(4):439-442. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13819. Epub 2018 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 29330890]

Patni R. Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. Journal of mid-life health. 2019 Jul-Sep:10(3):111-113. doi: 10.4103/jmh.JMH_125_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31579156]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 31576044]

Barjon K, Mahdy H. Episiotomy. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536281]

Borrman MJ, Davis D, Porteous A, Lim B. The effects of a severe perineal trauma prevention program in an Australian tertiary hospital: An observational study. Women and birth : journal of the Australian College of Midwives. 2020 Jul:33(4):e371-e376. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2019.07.301. Epub 2019 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 31537498]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOranges CM, Sisti A, Sisti G. Labia minora reduction techniques: a comprehensive literature review. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2015 May:35(4):419-31. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25908699]

Hersant B, Jabbour S, Noel W, Benadiba L, La Padula S, SidAhmed-Mezi M, Meningaud JP. Labia Majora Augmentation Combined With Minimal Labia Minora Resection: A Safe and Global Approach to the External Female Genitalia. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Apr:80(4):323-327. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001435. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29461295]

Acimi S, Bessahraoui M, Acimi MA, Abderrahmane N, Debbous L. Vaginoplasty and creating labia minora in children with disorders of sex development. International urology and nephrology. 2019 Mar:51(3):395-399. doi: 10.1007/s11255-018-2058-8. Epub 2018 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 30547360]

Learner HI, Creighton SM, Wood D. Augmentation vaginoplasty with buccal mucosa for the surgical revision of postreconstructive vaginal stenosis: a case series. Journal of pediatric urology. 2019 Aug:15(4):402.e1-402.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.019. Epub 2019 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 31351946]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNegussie D. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: a case report. Ethiopian medical journal. 2007 Jul:45(3):307-12 [PubMed PMID: 18330332]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChormanski D, Muzio MR. 17-Hydroxylase Deficiency. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31536251]