Introduction

Researchers do not agree on one comprehensive "fascia" definition. Despite the scientific uncertainty, there is an agreement with medical text that the fascia covers every structure of the body, creating a structural continuity that gives form and function to every tissue and organ. The fascial tissue has a ubiquitous distribution in the body system; it is able to wrap, interpenetrate, support, and form the bloodstream, bone tissue, meningeal tissue, organs, and skeletal muscles. The fascia creates different interdependent layers with several depths, from the skin to the periosteum, forming a three-dimensional mechano-metabolic structure [1].

The Fascia and Its Effect on Individual Health [2][3]

Three large groups of scholars have attempted to define fascia. The Federative Committee on Anatomical Terminology (FCAT), founded in 1989 from the General Assembly of the International Federation of Associations of Anatomists (IFAA), introduced the term "fascia superficialis" and "fascia profunda." The superficial fascia is a “whole loose layer of subcutaneous tissue lying superficial to the denser layer of fascia profunda.” The deep fascia, according to this definition, lies below the superficial fascia, highlighting two fasciae. In 2011, the Federative International Programme on Anatomical Terminologies (FIPAT), in agreement with FCAT, defined the fascia as “a sheath, a sheet, or any other dissectible aggregations of connective tissue that forms beneath the skin to attach, enclose, and separates muscles and other internal organs.” The FIPAT builds on the text of international anatomical terminology. The second definition specifies the term connective tissue, which functions to divide, separate, and support different structures. The connective tissue or fascia begins under the skin, excluding the epidermis from the fascia set.

The third group of scholars is the Fascia Nomenclature Committee (2014), born from the Fascia Research Society founded in 2007. The board gave the following description of fascia: “The fascial system consists of the three-dimensional continuum of soft, collagen-containing, loose and dense fibrous connective tissues that permeate the body. It incorporates elements such as adipose tissue, adventitia, and neurovascular sheaths, aponeuroses, deep and superficial fasciae, epineurium, joint capsules, ligaments, membranes, meninges, myofascial expansions, periosteum, retinacula, septa, tendons, visceral fasciae, and all the intramuscular and intermuscular connective tissues including endo-/peri-/epimysium. The fascial system interpenetrates and surrounds all organs, muscles, bones and nerve fibers, endowing the body with a functional structure, and providing an environment that enables all body systems to operate in an integrated manner.” This is the broadest definition of fascia. The concept of a continuum of the collagen and connective structure, the cellular diversity that makes up the fascia, is emphasized. It is this continuum itself that assures the health of the body.

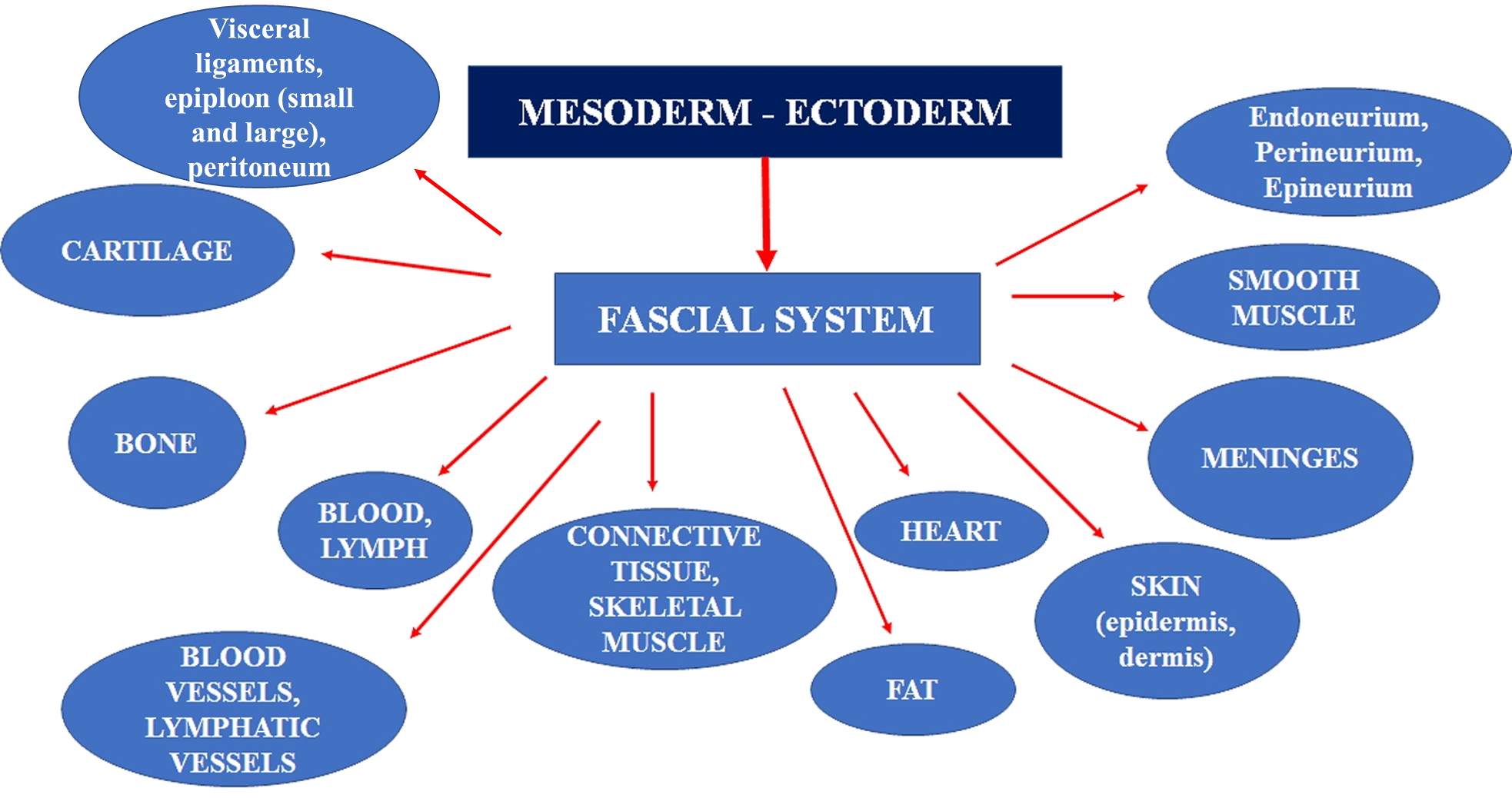

These scientific definitions allow healthcare practitioners to make some deductions about fascia. The fascia includes everything that presumes the presence of collagen/connective tissue or from which it is derived. All the tissue considered as "specialized connective tissue" of mesodermal derivation is inserted into the fascial system. These include blood, bone, cartilage, adipose tissue, hematopoietic tissue, and lymphatic tissue. The fascial system has no discontinuity in its path, with layers of different characteristics and properties overlapping.

A further research group for the nomenclature of the fascia founded in 2013: FORCE - Foundation of Osteopathic Research and Clinical Endorsement. The FORCE group has recently written several articles, highlighting new concepts to understand the concept of the fascia better: " The fascia is any tissue that contains features capable of responding to mechanical stimuli. The fascial continuum is the result of the evolution of the perfect synergy among different tissues, liquids, and solids, capable of supporting, dividing, penetrating, feeding, and connecting all the districts of the body: epidermis, dermis, fat, blood, lymph, blood and lymphatic vessels, tissue covering the nervous filaments (endoneurium, perineurium, epineurium), voluntary striated muscle fibers and the tissue covering and permeating it (epimysium, perimysium, endomysium), ligaments, tendons, aponeurosis, cartilage, bones, meninges, involuntary striated musculature and involuntary smooth muscle (all viscera derived from the mesoderm), visceral ligaments, epiploon (small and large), peritoneum, and tongue. The continuum constantly transmits and receives mechano-metabolic information that can influence the shape and function of the entire body."[4][5]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Mechanical Function

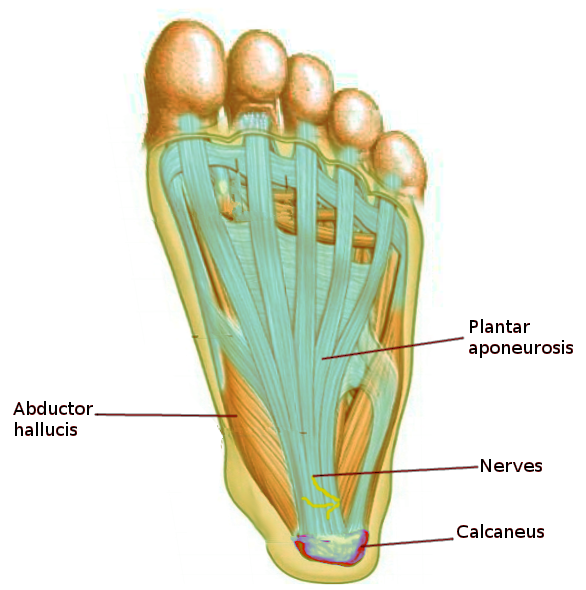

Normal movement of the body is allowed because of the presence of the fascial tissues and their inseparable interconnection, which allow the sliding of the muscular structure, the sliding of nerves and vessels between contractile fields and joints, and the ability of all organs to slide and move with each other as influenced by the position of the body. One of the fundamental characteristics of the fascia is the ability to adapt to mechanical stress, remodeling the cellular/tissue structure and mirroring the functional necessity of the environment where the tissue lays. For example, the plantar fascia in the foot adopts a mechanical model known as the "windlass mechanism" in order to provide dynamic support for the medial longitudinal arch while the limb transitions from the heel strike to toe-off phases of the gait cycle[6].

The fascial continuum allows the proper distribution of tension information produced by different tissues covered or supported by the fascia so that the entire body system can interact in real-time, including the epidermis.

Emotional Function[7]

The fascial unity influences not only movement but also emotions. Dysfunction of the fascial system that is perpetuated in everyday movements can cause an emotional alteration of the person. This emotional alteration could be established originating from constant myofascial nonphysiological afferents, which would bring the emotional state and the myofascial pathology to the same level. In fact, the position of the body stimulates areas of emotionality, and the presence of myofascial alterations leads to postural alterations.

The myofascial system has a very fine, wide, diversified, and ever-present innervation. In particular, we can find the myelinated proprioceptive terminations (Ruffini, Golgi, and Pacini) inside or near the connective tissue in close relationship with the muscles where a multitude of very fine, unmyelinated-free terminations are in contact with the periosteum, the layers such as endomysium and perimysium, and in the connective tissue of all the viscera. These receptors are deputies to the functions of proprioception, nociception, and interoception. The afferent pathways of the interception project to the autonomic and medullary centers and to the brainstem, where they are sorted by the anterior cingulate cortex and the posterior dorsal insula, thanks to the thalamocortical extension. Interoception can modulate the exteroceptive representation of the body as well as pain tolerance; dysregulation of the pathways that manage or stimulate the interoception could cause a distortion of one's body image and influence emotionality.

Embryology

Many tissues derive from the connective tissue, such as blood, bones, cartilage, lymphoid and hematopoietic tissue, fat, tendons, ligaments, peri/epi/ endomysium, meningeal, all visceral communication, and coverage fasciae from the mesenchyme. During embryonic development, the connective tissue influences the form (morphogenesis) of the structures that it will contain and connect.

The embryonic mesenchyme or connective embryonic or undifferentiated mesenchyme is formed by star-branched cells with a high mitotic rate (high reproductive capacity); they are considered pluripotent cells, as they can differentiate into different tissues. Embryonic mesenchyme will not only be the source of many connective structures but also stromal stem cells. During development, they occupy the spaces between embryonic layers by connecting the various structures and constituting the organ stroma.

The mesenchyme is found and is derived from all three embryonic layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm), especially mesoderm and ectoderm. For current information and animal models, all structures within the fascia definition that form part of the head (muscles, bones, skin, etc.) and part of the cervical tract are derived from mesoderm and ectoderm. [8]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Blood and lymph derive from mesoderm and are considered connective tissues.

In addition to the nutritive functions, blood also provides a way of linking to different organs which can communicate with each other through hormones and chemical mediators, guaranteeing the integration of the functions of the organism. The vehicle of immune cells and platelets can reach places where their presence is necessary; for example, areas of inflammation, of antibodies and proteins of the clotting system, and of the numerous transport proteins such as lipoproteins, transferrin, ceruloplasmin, and albumin to which the water-insoluble compounds that circulate in blood are attached.

Blood is connective tissue. It consists of cells and cell fragments in suspension in an extracellular matrix of complex composition. The unusual characteristic of blood is that the extracellular matrix is a liquid, which means that blood is fluid connective tissue. There are two different components in blood that can be separated by centrifugation: (1) a fluid matrix called plasma and (2) corpuscles, which are cells or cell fragments.

Corpuscles are erythrocytes, platelets, and leukocytes. Only leukocytes are complete cells; erythrocytes are anucleate cells, and platelets are cell fragments. Erythrocytes are present in larger quantities than the other elements, which is why they influence the value of the hematocrit much more than leukocytes or platelets, which make up around 1% of the total volume. Like the other elements, Erythrocytes are generated by pluripotent stem cells located in the bone marrow, particularly in ribs, sternum, pelvis, and vertebrae.

There are different kinds of leukocytes. Granulocytes are characterized by the presence of big granules in the cytoplasm. They are visible in the optical microscope after coloring and are divided into neutrophils (with an affinity to neutral coloring), eosinophils (color with acid coloring), basophils (with an affinity to basic coloring). Lymphocytes, which include lymphocytes T, lymphocytes B, and natural killer cells, participate in specific defense: firstly, they recognize a pathogen, target it, and then attack it. The targeted answer implies almost always the production of proteins circulating in the blood, called antibodies. Monocytes are the biggest leukocytes, characterized by a big, horseshoe-shaped nucleus.

The Lymphatic System

The lymphatic system effectively removes the excess of interstitial fluids, solutes, and various cells and guides them towards the bloodstream, maintaining the volume of plasma and interstitial fluids in constant balance. The lymphatic system originates from the interstitial tissue called “initial lymphatics,” small capillaries delimited by discontinuous endothelium and basement membrane and low resistance to the flow of fluids and substances (hydrophiles molecules, cells, viruses, and bacteria). They attach to the external surface of the cells through collagen fibrils (collagen type VII). This collagen allows the transmission of mechanical forces towards the lumen of the lymphatic vessel; there is an autonomous contraction in some vessels, thanks to filaments similar to actin. These initial lymphatics become wider, creating collecting ducts that consist of collagen, smooth muscle cells, and elastic fibers. According to recent data, lymphatic vessels have their tone and, probably, their intrinsic contraction autonomy with a high ability of sensibility to flow variation (sensory functions). They are surrounded by nerves of the autonomous system, mainly sympathetic fibers, which could act to better coordinate the lymphatic transport. Lymphatic vessels adapt and change their elastic capacity, improving or worsening the function of lymphatic transport.

There are primary valves formed by the cytoplasmic extent of the adjacent endothelial cells linked by close connections. The valves of these cells protrude towards the inside; this way, what goes in cannot go out. Finally, the intraluminal valves (weaker) are two sheets attached to the opposite sides of the lymphatic vessel and connected to zonules (perimeter junction involving a band that surrounds the cell). Lymph flows due to external mechanical compressions, for example, the one caused by muscle contraction and to its intrinsic contraction abilities.

The lymphatic system is subject to aging, losing its elasticity and creating “aneurysms” over time, or decreasing the number of blood vessels or lymphangions (the lymphatic functional unit). Recent evidence reveals that lymphatic vessels are supported by a nervous system of vagal cholinergic type and sympathetic type, able to modulate the contraction (peristalsis, also helped by the breathing and pulsation of arteries) of vessels endowed with contractile fibers (with an actin-like protein). These thin nerves reach the external layer of the lymphatic vessel and then reach the deepest endothelial layer; this nerve network deteriorates in older people. The presence of both the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems is probably as tension or vessel tone modulators and as a sensor of the vessel's contractile layer.

The Dural System

The dural system has a lymphatic system called the glymphatic system. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is drained through the venous system and the lymphatic system.

Dural lymphatic vessels place themselves side by side to the veins and arteries of the brain; more specifically, they come out of the skull, following the reverse path of the pterygopalatine artery and a branch of the internal carotid, and travel through external vein paths to the skull and through cranial nerves that come out of the skull.

Lymphatic vessels follow vein paths of the cribriform plate towards the nasal mucosa, following ways exiting the CSF. The lymphatic system absorbs the interstitial liquid and the CSF from the subarachnoid space and transports it outside of the skull, more specifically, from the base, up to the cervical spine. This mechanism is stronger during sleep.

Nerves

The innervation that affects the fascial system is autonomous: sympathetic and parasympathetic. The fascial system constitutes the same nerve structure (epi/peri/endoneurium). All layers are innervated and have a thin but potentially important plexus of nociceptors

The sliding of the fascia structures that make up the nerve and the sliding of the nerve between the various tissues that it crosses and innervates is fundamental for the health of the nerve.

Muscles

Connective System Organization Gives the Shape of the Muscles[9]

The fascial structure largely gives its ability to transmit the produced force. The latter not only functions as a transporter of the produced mechanical tension but stores mechanical energy to save myoelectric energy. The connective tissue that determines the various muscular layers derives in great proportion from the fibroblast.

Muscles play a valuable role in managing the mechanical tension produced and felt by rapidly changing the morphology of their cytoskeleton; this mechanism is facilitated by the intervention of fibroblasts. If the mechanical stimulation felt by the myofascial system (connective and contractile tissue) is present for a short period, the morphological change will be transient. If the mechanical forces persist in reshaping the myofascial system, there will be a chronic change in form and function.

Every fibroblast, potentially, is aware of the functional state of the one close to it as well as those distant from it, ensuring the fascial and mechanical continuity. In the connective tissue, there are other types of cells not yet wholly studied and cataloged.

In the superficial and deep fascial tissue that covers and divides the muscle, cells like fibroblasts are called fasciacytes. These cells specialize in the production of hyaluronic acid (high molecular weight glycosaminoglycan polymer of ECM); the latter allows dampening of the tensions, fills the cell spaces, and allows sliding of the different tissue layers. They most likely will reside in the areas with the greatest presence of innervation (nerve endings, Pacini, and Ruffini corpuscles).

Another type of cell found in the connective tissue is the telocyte. There are few studies on such cells in the fascial field, particularly for the latae fascia, thoracolumbar, crural, and plantar. They are found in many tissues of the human body and are involved in many biological processes. Telocytes form a network in the fascial network. They can form homocellular junctions (including telocytes) and heterocellular (telocytes and fibroblasts, endothelial cells, stem cells, adipocytes, etc.). Through these contacts, they can influence the metabolic environment and play a role in repair and remodeling. Probably, the telocytes can influence the production of hyaluronic acid. The exact role of these cells in the fascia is still unknown.

Surgical Considerations

Scars

Surgical adhesions are the result of a lack of sliding between the various fascial layers. This absence or reduction of movement causes an inflammatory environment, which creates adhesions. The adhesions then vascularize and innervate, constituting an autonomous tissue compared to surrounding tissues. These adhesions could be the reason for recurrent pain in many postsurgical syndromes.

Clinical Significance

The muscular system is part of the fascial continuum, and in the presence of systemic diseases and disorders of the visceral, genetic, vascular, metabolic, and alimentary type, it undergoes a nonphysiological alteration of its function. The epigenetic processes lead to adaptation in response to a lack of mechanotransductive, causing a further decline in its properties.[10]

Chronic Fatigue

Chronic fatigue can be related to the fascial system, especially if the pathological disorder has been present for several years. If the fascia becomes fibrotic or if the layers of the tissues do not flow properly, bodily movements will be difficult. The movements will be uncoordinated, producing more anaerobic metabolites, which will be recorded by the central nervous system as fatigue. An example is fibromyalgia.

Increased levels of circulating cytokines from the connective tissue system, triggered by systemic diseases, could cause neuropathic pain. Connective tissue can directly send pain signals; it possesses nociceptors capable of translating a mechanical stimulus into painful information, and if there are non-physiological mechanical stimuli, proprioceptors can become nociceptors. The nociceptors themselves synthesize neuropeptides that can alter the surrounding tissue and form an inflammatory environment. The epineurium and perineurium are part of the fascial system innervated by nervi nervorum, which, if in contact with pro-inflammatory molecules, can cause sensations of pain and create a vicious circle.

All the fascial layers need hyaluronic acid to slip one on the other. Decreased quantity or non-homogeneous distribution comprises the ability of local or systemic sliding of the connective tissue. There is much evidence that the change in the viscoelasticity of the fascial system is an important cause of nociceptor activation. Hyaluronic acid would become adhesive and less lubricating, altering the lines of forces within the different fascial layers. This mechanism could be one of the causes of joint stiffness and pain in the morning.

An alteration of the adjustable tension may derive from the contractile capacity of fibroblasts, creating a fascial tone that is independent of neurological intervention. This contractile mechanism could cause an inflammatory environment with fibroblast hyperplasia, resulting in chronic inflammation and sensitization of nociceptors. The inflammation that can be registered by fibroblasts will increase extracellular edema that does not depend exclusively on the increased vascular permeability but also on the loose fascial tissue that recalls liquids inside it. The edema will bring an increase in tension and rigidity, with difficulty in sliding the fascia layers and the appearance of pain. The described framework will stimulate the fibroblast to release ATP (adenosine triphosphate), stimulating the nociceptors.

The sensitization of nociceptors could derive from local ischemia caused by nonphysiological fascial tension, which prevents the proper functioning of the skeletal muscle and creates, for example, trigger points.

Immune Response

Fibroblasts influence the immune system and, consequently, the bone tissue; this relationship is osteoimmunology. The immune system and bone tissue share some molecular interactions, including transcription factors, signal molecules, and membrane receptors. In particular, osteoclasts sensitize cytokines and vice versa. When the fascial continuum fails to flow properly, its different layers, one on top of the other from the most superficial layer up to the periosteum, an inflammatory environment, acute or chronic, is created; the cytokines produced could stimulate the activation of osteoclasts and bone resorption, leading over time to an osteoporosis situation.

Fibrosis or fibromatosis is the result of disorganization of connective tissue with hyperplasia and hypertrophy of fibroblasts due to a chronic inflammatory environment, nonphysiological mechanical stress, or immobility. It is a recognized calcification phenomenon. When fibromatosis is registered as similar to scar tissue, for example, in Dupuytren pathology, the percentage of fibroblasts that change into myofibroblasts increases, with alteration of the tension that the fascial continuum senses. This creates a vicious circle of inflammation and activation of nociceptors as connective tissue is much more sensitive to nociceptor activation than muscle tissue.

Many chronic conditions, such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, fibromyalgia, diabetes, always show alterations in the fascial system. These changes make the symptomatic picture more burdensome for the patient.

Other Issues

Researchers must always be impartial in the path of knowledge, because the results will be used by clinicians for patients. There should be no copyrigth on fascial terminology, because the researcher does not have to aim to make money. [13]

Media

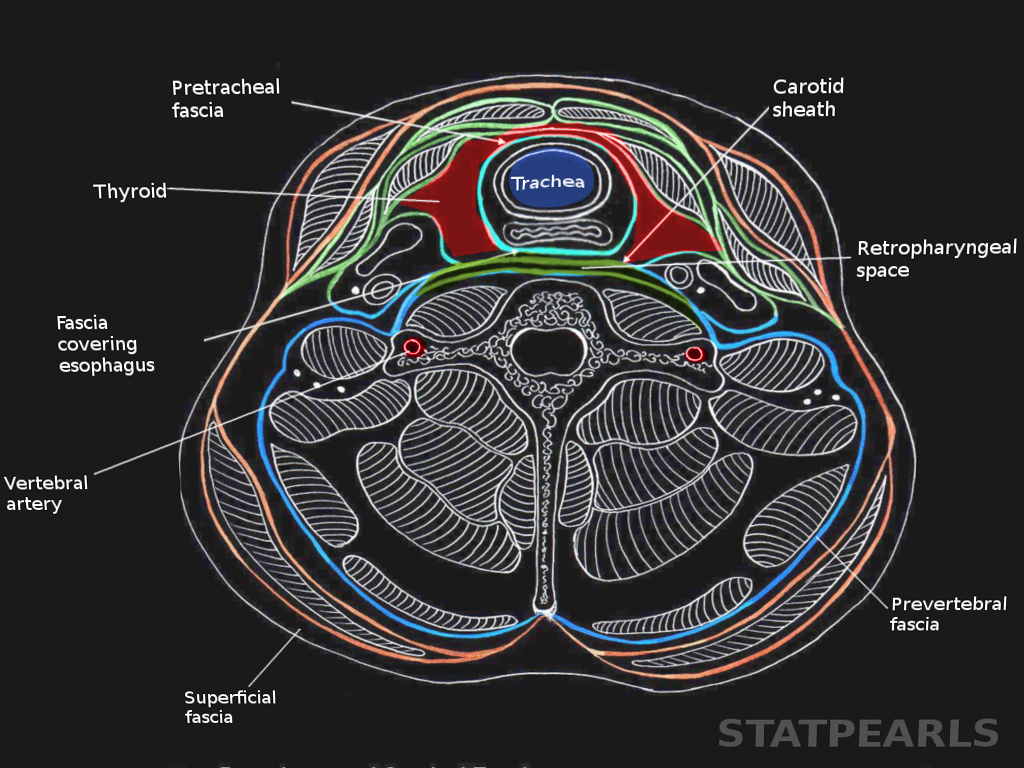

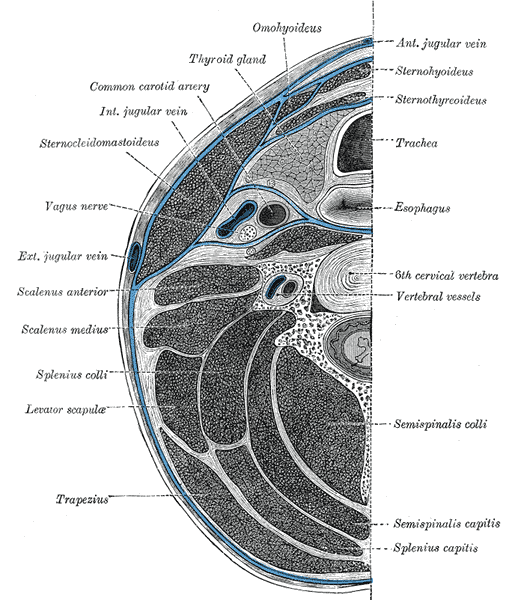

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cervical Fascia Layers, Anterior Jugular Vein, Sternohyoideus, Sternothyroideus, Trachea, Esophagus, 6th Cervical Vertebra, Vertebral vessels, Semispinalis Colli, Semispinalis Capitis, Splenius Capitis, Trapezius, Levator Scapula, Splenius Colli, Scalenus Medius, Scalenus Anterior, Exterior Jugular Vein, Vagus Nerve, Sternocleidomastoid, Interior Jugular vein, Common Carotid artery, Thyroid Gland, Omohyoideus

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bordoni B, Marelli F, Morabito B, Sacconi B. The indeterminable resilience of the fascial system. Journal of integrative medicine. 2017 Sep:15(5):337-343. doi: 10.1016/S2095-4964(17)60351-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28844209]

Wilke J, Schleip R, Yucesoy CA, Banzer W. Not merely a protective packing organ? A review of fascia and its force transmission capacity. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2018 Jan 1:124(1):234-244. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00565.2017. Epub 2017 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 29122963]

Adstrum S, Hedley G, Schleip R, Stecco C, Yucesoy CA. Defining the fascial system. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2017 Jan:21(1):173-177. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.11.003. Epub 2016 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 28167173]

Bordoni B, Simonelli M, Morabito B. The Other Side of the Fascia: Visceral Fascia, Part 2. Cureus. 2019 May 10:11(5):e4632. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4632. Epub 2019 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 31312558]

Bordoni B, Escher AR, Tobbi F, Ducoux B, Paoletti S. Fascial Nomenclature: Update 2021, Part 2. Cureus. 2021 Feb 11:13(2):e13279. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13279. Epub 2021 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 33604227]

Bourne M, Talkad A, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb, Foot Fascia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30252299]

Bordoni B, Marelli F. [Emotions in Motion: Myofascial Interoception]. Complementary medicine research. 2017:24(2):110-113. doi: 10.1159/000464149. Epub 2017 Mar 10 [PubMed PMID: 28278494]

Bordoni B, Morabito B. Reflections on the Development of Fascial Tissue: Starting from Embryology. Advances in medical education and practice. 2020:11():37-39. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S232947. Epub 2020 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 32021541]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchleip R, Wilke J, Schreiner S, Wetterslev M, Klingler W. Needle biopsy-derived myofascial tissue samples are sufficient for quantification of myofibroblast density. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2018 Apr:31(3):368-372. doi: 10.1002/ca.23040. Epub 2018 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 29314236]

Bordoni B, Marelli F, Morabito B, Sacconi B. Emission of Biophotons and Adjustable Sounds by the Fascial System: Review and Reflections for Manual Therapy. Journal of evidence-based integrative medicine. 2018 Jan-Dec:23():2515690X17750750. doi: 10.1177/2515690X17750750. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29405763]

Bordoni B, Marelli F, Morabito B, Sacconi B, Severino P. Post-sternotomy pain syndrome following cardiac surgery: case report. Journal of pain research. 2017:10():1163-1169. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S129394. Epub 2017 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 28553137]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilke J, Schleip R, Klingler W, Stecco C. The Lumbodorsal Fascia as a Potential Source of Low Back Pain: A Narrative Review. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():5349620. doi: 10.1155/2017/5349620. Epub 2017 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 28584816]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBordoni B, Escher AR, Tobbi F, Pranzitelli A, Pianese L. Fascial Nomenclature: Update 2021, Part 1. Cureus. 2021 Feb 14:13(2):e13339. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13339. Epub 2021 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 33643754]