Introduction

The human face is made up of many muscles, vessels, glands, tissues, and organs. Among the most distinct features on the human face are the cheeks. To the naked eye, the cheeks appear only as a small part of the face.

The cheeks are described as the region below the eyes but above the jawline. The cheeks span between the nose and the ears. The cheeks are made up of many muscles, fat pads, glands, and tissues. This complex composition allows the checks to participate in eating, talking, and facial expression.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Many structures help make up the cheeks. The superficial layer of the cheeks is skin. The skin on the face is similar to most skin in the human body. The skin is the first line of defense from the outside environment. As a part of the immune system, the cheeks contain hairs that help maintain homeostasis and glands that provide an antimicrobial defense.

Slightly deeper to the skin is the fat pads. The fat pads contribute to the contour and the fullness of the cheeks. The fat originates from different regions in the face, but all come together at the cheek. The fat that provides fullness to the superior part of the cheek comes from the infraorbital and lateral orbital fat pads. The fat that contributes fullness to the medial region of the cheek comes from the nasolabial fat pads. The area considered to be the middle cheek derives from middle and superficial medial fat pads. The lower border of the cheek contains superior jowl fat. The fat makes up the lateral region of the cheek comes from the distal part of the lateral temporal fat pad.

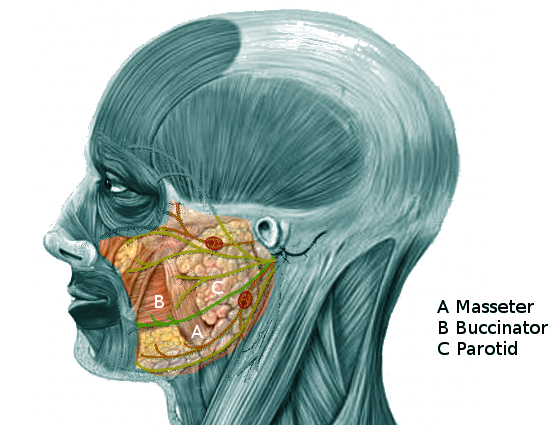

The lateral region of the cheek also contains the parotid gland. The parotid gland also contributes to the fullness of the cheek. The parotid gland also secretes digestive enzymes into the oral cavity for digestion.

Deep to the fat pads are the muscles. There are many muscles in the cheek region. The masseter muscle is the largest in the cheek region. The masseter contributes to the lateral fullness of the cheek, but its primary function is mastication. The lower part of the orbicularis oculi muscle contributes to the superior part of the cheek. The levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle is on the lateral border of the nose, and it demarcates the medial contour of the cheek region. The muscle lateral to the levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle is the levator labii superioris, it is part of the medial cheek region. The zygomaticus minor muscle and the zygomaticus major muscle contributes to the middle cheek region. The zygomaticus major also has some attachment in the superior cheek region. Slightly lower to the zygomaticus muscles, the risorius muscle and the levator anguli oris lays. These two muscles attach to the angle of the mouth. Deep to all these muscles, lies the buccinator muscle. The buccinator muscle’s function is to hold food boluses in the mouth against the teeth during mastication.

The three bony structures that help form the cheek are the zygomatic bone, the maxilla bone, and the mandibular bone. The zygomatic bone and the maxilla bone makes up the superior bony region of the cheek. The maxilla bone also makes the medial bony region of the cheek. The mandibular bone makes the lower region and lateral bony regions of the cheek.

All of these structures work in sync to aid in digestion, talking, and facial expression. The cheek aids in enzymatic digestion by the secretion of the enzymes from the parotid gland. While in mechanical digestion, the cheek aids in maintaining the food in the mouth so that it can be chewed and swallowed. The majority of the muscles in the cheek region contribute to facial expression. The various facial expressions result from muscle contractions and changes in blood flow that manifest physically through the cheeks.

Embryology

During fetal development, the cheek is derived mainly from the first and second branchial arches. The first and second branchial arches will form the bone and musculature in the cheeks. The first and second branchial pouches will development into the nerves and vessels that are within the cheek. The skin that overly the cheeks and the nerve innervation will derive from the ectoderm. The parotid gland also forms from the ectoderm layer. The mesenchyme tissue from the mesoderm layer will differentiate into blood vessels, muscles, and connective tissues.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The main blood supply for the cheek is from the facial artery and the transverse facial artery. Both of these arteries are branches of the external carotid artery. The facial artery and the transverse facial artery will supply the majority of the cheek. The medial border of the cheek will receive blood from the angular artery. The angular artery is the facial artery's terminal branch that ascends the tear trough (lateral contour of the nose). The superior border of the cheek also receives blood from the zygomatic-orbital artery. These arteries will go onto and form many anastomoses to provide collateral blood flow to the cheeks and its structures.[1]

The lymph in the cheek regions drains into the preauricular or the submandibular lymph nodes. The medial and inferior regions of the cheek will drain towards the submandibular lymph nodes. The lateral and superior regions of the cheek will drain towards the preauricular lymph nodes. All the lymph from the right cheek will drain back into the right lymphatic duct while the left cheek will drain back into the thoracic duct.

Nerves

The cheek region receives innervation from the facial nerve and the trigeminal nerve. The facial nerve will ascend toward the face after exiting the stylomastoid foramen. The facial nerve will travel through the parotid gland. The facial nerve will split the parotid gland into two main lobes. As the facial nerve exits the parotid gland, it splits into five main branches: frontal, zygomatic, buccal, marginal mandibular, and cervical. The buccal branch will innervate the majority of the muscles in the cheek region except for the orbicularis oculi and the masseter muscle. Innervation of the orbicularis oculi muscle is from the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve. The facial nerve's innervation will coordinate the contraction of facial muscles. The different combinations of facial muscle contractions will produce various facial expressions. The trigeminal nerve will give sensory innervation to the entire face, including the cheeks. The trigeminal nerve also delivers motor innervation to the masseter muscle.[2]

Muscles

Muscles located in the cheek region:

- Orbicularis oculi muscle (lower border)

- Levator labii superioris muscle

- Levator labii superioris alaeque nasi muscle

- Risorius muscle

- Levator anguli oris muscle

- Zygomaticus major and minor muscles

- Buccinator muscle

- Masseter muscle

Most of the muscles in the cheek region will participate in facial expression except for the buccinator and the masseter muscle. The buccinator muscle is the muscle closes to the oral cavity. The buccinator muscle is the primary muscle that will participate in supporting the food bolus in the mouth during chewing and swallowing. The masseter muscle is the only muscle located in the cheek region and engages in mastication.

Physiologic Variants

The amount of adipose tissue in the fat pads in the cheeks may vary from person to person. The amount of fat accumulation in the cheeks may vary due to genetics and lifestyle. Everyone will have cheeks, but the size and contours of the cheek will vary greatly. The variations in the cheeks are what gives each person their unique facial features. The personalization of the face allows for facial identification/recognition of person to person.[3] One of the common variations is blushing. Individuals of fair skin color tend to present with more pronounced blushing. The pronounced blushing is due to cutaneous capillaries that vasodilate and increase perfusion to the cheeks.[4] Another common variation in the cheeks are the dimples. Dimples are the result of a variation in the zygomaticus muscle. The duplication or bifurcation splitting of the zygomaticus muscle manifests physically as facial dimples. Dimples only appear in some individuals while absent in other people.[5]

Surgical Considerations

The anatomy of the cheek is vital in cosmetic procedures. Surgeons commonly alter the cheeks during the procedure termed "facelift". During facelifts, the skin of the cheeks is dissected and separated from the face. The underlying fat may be liposuction away. The nerve branches from the facial nerve may be injured if the surgeon is not careful. The most common nerve damaged during a facelift is the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve. Even though the zygomatic branch is most commonly injured, there is cross innervation from the buccal branch of the facial nerve. This cross innervation prevents visible nerve damage. The buccal branch is the nerve that most surgeons try to avoid damaging. If there is damage to the buccal nerve, there will be drooping of the cheeks. Unfortunately, the regions innervated by the buccal branch of the facial nerve do not have cross innervation from other nerves.[6][7]

The excision of the parotid gland due to cancers can result in facial nerve damage if there is improper technique. The facial nerve penetrates through the parotid gland before branching inside the gland. When the parotid gland gets dissected, the facial nerve is commonly damaged if cancer affects the nerve itself or the surgeon accidentally damages the nerve during surgery.

During facial reconstruction surgery, the knowledge of the cheek and the face will allow for the taking of appropriate precautions. The precautions will prevent damage to the muscles, nerves, and vasculature that may result in an unsuccessful surgery.

Clinical Significance

The cheek region is one of the first features seen on a person. The cheeks can serve as an objective assessment of temperature in an individual. In children, the cheeks are commonly affected by acne. Acne is a skin disease that affects the sebaceous duct and gland. The lesions appear on the face as comedones. The comedones may vary as blackheads, whiteheads, or pustules.

In adults, the face is prone to sunlight exposure and skin damage. The cheeks are a common area for dermatologic diseases. Since the cheeks are commonly exposed to the sun, malignancies may arise from the damaged skin. There is a dose-dependent effect on cancers and direct sun exposure.[8]

In autoimmune conditions, there is a classic malar rash that appears in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The rash results from inflammation from the autoimmune nature of SLE.

The cheeks and the nasolabial folds are used along with the forehead wrinkles to differentiate between a stroke and Bell palsy. In Bell palsy, there will be a complete loss of forehead wrinkling and absent nasolabial folds. Bell palsy is a disorder affecting the facial nerve. The facial nerve is usually affected as it exits the stylomastoid foramen. In a stroke, the patient will have drooping of the face, but the forehead wrinkling will still be intact. Bell palsy is a lower motor neuron defect while a stroke is an upper motor neuron defect.[9]

The most common pathologies affecting the cheeks will be dermatological or malignancy.[10][11]

Other Issues

The cheeks can present with pathognomonic rashes and lesions that will aid in diagnosing certain diseases. The cheeks can be used to assess patients subjectively. The fat from the cheeks is commonly lost when there is a significant amount of weight loss. Patients with cancer, HIV, and starvation will present will a significantly reduced amount of fat in the cheeks. So the cheeks can be used to indicate/predict nutritional status.[12][13]

Media

References

Meegalla N, Sood G, Nessel TA, Downs BW. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Facial Arteries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725617]

Yu M, Wang SM. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Zygomatic. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31334977]

Ansari A, Bordoni B. Embryology, Face. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424786]

Thorstenson CA, Pazda AD, Lichtenfeld S. Facial blushing influences perceived embarrassment and related social functional evaluations. Cognition & emotion. 2020 May:34(3):413-426. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2019.1634004. Epub 2019 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 31230523]

Phan K, Onggo J. Prevalence of Bifid Zygomaticus Major Muscle. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019 May/Jun:30(3):758-760. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005261. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30807476]

Jacono AA, Bryant LM, Alemi AS. Optimal Facelift Vector and its Relation to Zygomaticus Major Orientation. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2020 Mar 23:40(4):351-356. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz114. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30997513]

Kreutz-Rodrigues L, Shapiro D, Mardini S, Bakri K. Landmarks in Facial Rejuvenation Surgery: The Top 50 Most Cited Articles. Aesthetic surgery journal. 2020 Jan 1:40(1):NP1-NP7. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjz207. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31362303]

Zalaudek I, Conforti C, Corneli P, Jurakic Toncic R, di Meo N, Pizzichetta MA, Fadel M, Mitija G, Curiel-Lewandrowski C. Sun-protection and sun-exposure habits among sailors: results of the 2018 world's largest sailing race Barcolana' skin cancer prevention campaign. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2020 Feb:34(2):412-418. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15908. Epub 2019 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 31442352]

Fujiwara T, Namekawa M, Kuriyama A, Tamaki H. High-dose Corticosteroids for Adult Bell's Palsy: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2019 Sep:40(8):1101-1108. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000002317. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31290805]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGirardi FM, Nunes AB, Hauth LA. Malignant subcutaneous PEComa on the cheek. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2018 Nov/Dec:93(6):934-935. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187595. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30484551]

Hasan Z, Tan D, Buchanan M, Palme C, Riffat F. Buccal space tumours. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2019 Apr:46(2):160-166. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2018.06.011. Epub 2018 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 30031665]

Zheng LF, Chen PJ, Xiao WH. [Signaling pathways controlling skeletal muscle mass]. Sheng li xue bao : [Acta physiologica Sinica]. 2019 Aug 25:71(4):671-679 [PubMed PMID: 31440764]

Tomasin R, Martin ACBM, Cominetti MR. Metastasis and cachexia: alongside in clinics, but not so in animal models. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2019 Dec:10(6):1183-1194. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12475. Epub 2019 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 31436396]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence