Introduction

The abdomen describes a portion of the trunk connecting the thorax and pelvis. An abdominal wall formed of skin, fascia, and muscle encases the abdominal cavity and viscera. The abdominal wall does not only contain and protect the intra-abdominal organs but can distend, generate intrabdominal pressure, and move the vertebral column. Detailed knowledge of the components of the abdominal wall is essential for surgeons both in understanding the pathology affecting it and planning surgical access to the abdominal cavity. Abdominal wall defects may be either congenital or acquired and can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

In contrast to the thorax and pelvis, the abdomen is relatively deficient in skeletal support, comprising of only the vertebral column and lower ribs posteriorly. The abdominal wall connects to the skeletal framework at the thoracic cage superiorly and pelvic bones inferiorly. This relative bony deficiency allows flexibility of the trunk as well as distensibility to accommodate dynamic changes in the volume of abdominal contents. The abdominal wall has several different layers that are essential to understand when making surgical incisions. From superficial to deep, these layers include:

- Skin

- Subcutaneous tissue, which can further subdivide into:

- Camper’s fascia - a superficial fatty layer

- Scarper’s fascia - a deep membranous layer

- Abdominal muscles, their investing fascia, and aponeuroses

- Transversalis fascia

- Parietal peritoneum

The abdominal wall performs several vital functions. It contains and provides a scaffold for the development and functioning of abdominal viscera. All layers contribute to a degree of physical protection of the organs. The abdominal muscles may be divided broadly into anterolateral and posterior components. Anterolateral muscles include five paired muscles: the external oblique, internal oblique, transversus abdominis, rectus abdominis, and pyramidalis.[2] Posterior muscles include psoas major and quadratus lumborum bilaterally. The abdominal muscles contribute to movements of the trunk, including flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation. Simultaneous contraction of abdominal muscles can facilitate the generation of intraabdominal and intrathoracic pressure critical in sneezing, coughing, vomiting, and defecating. This action may also help stabilize the trunk when lifting heavy loads. In times of increased physiological or pathological demand for airway ventilation, the anterolateral muscles (except transversus abdominis) act as accessory muscles of respiration by depressing the ribs to cause active expiration.

Surface Anatomy

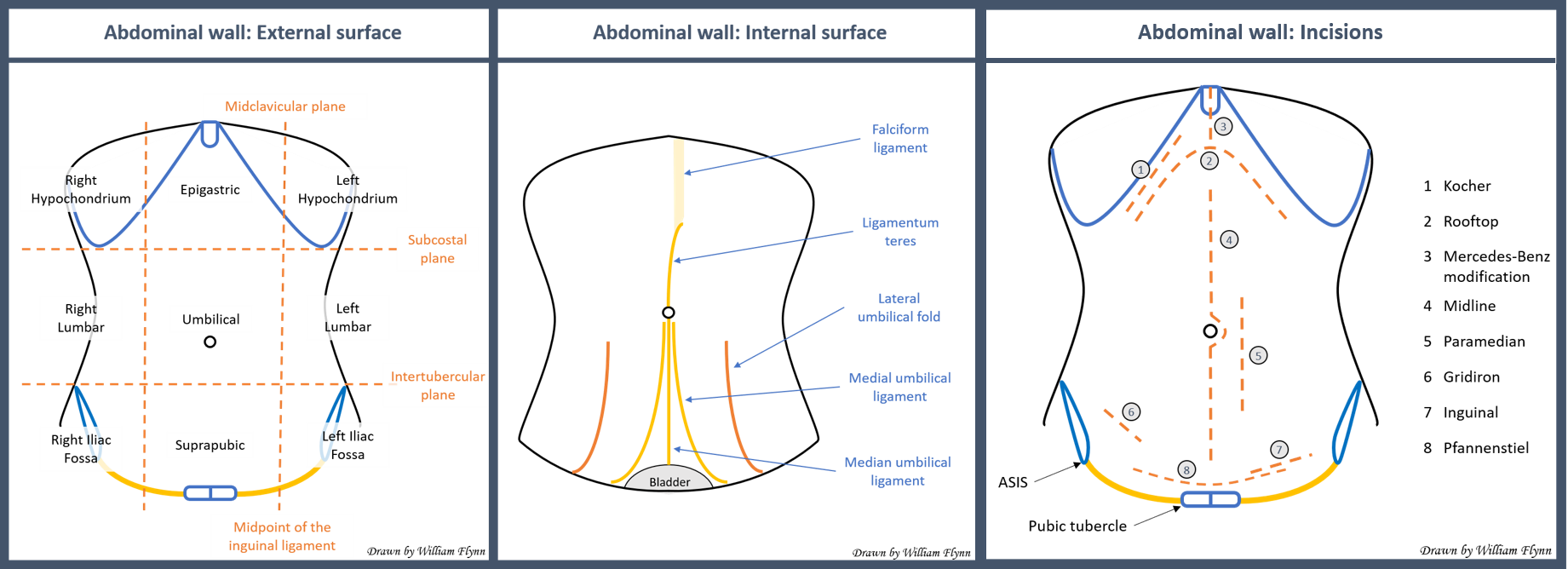

The external surface of the abdominal wall can be subdivided into regions to allow an accurate description of examination findings. Vertical lines are drawn along the midclavicular plane from the midclavicular point to the mid inguinal point. Horizontal lines can be drawn across the subcostal plane (the most inferior aspect of the anterior thoracic cage) and the intertubercular plane (in line with the iliac tubercles). These two vertical and two horizontal lines divide the abdomen into nine regions. Alternatively, one can divide the abdomen into four quadrants by a vertical median line and a horizontal line across the transumbilical plane.

The internal surface of the anterior abdominal wall can be appreciated clearly when the peritoneal space is entered and inflated during laparoscopic surgery. Several folds and ligamentous landmarks are visible. The ligamentum teres is the vestigial remains of the umbilical vein and runs in the free edge of the falciform ligament. It divides the liver into right and left anatomical lobes and travels along the inner surface of the anterior abdominal wall to the umbilicus. There are five folds or ligaments seen inferiorly to the umbilicus. In the midline is the median umbilical ligament, which is a remnant of the fetal urachus and runs from the umbilicus to the bladder. Medial umbilical ligaments are the remains of obliterated umbilical arteries and are visible either side of the median ligament. Lateral umbilical folds transmit the inferior epigastric vessels from the femoral ring to the arcuate line.

Embryology

At 3 to 4 weeks gestation, the embryo changes morphology from a disc to a fetal shape. This change involves the ectodermal disc layer folding to form the neural tube and the endodermal and mesodermal disc layers folding in the opposite direction to form the gut tube and ventral body wall. The mesoderm develops into the musculature and fascia of the abdominal wall.[3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

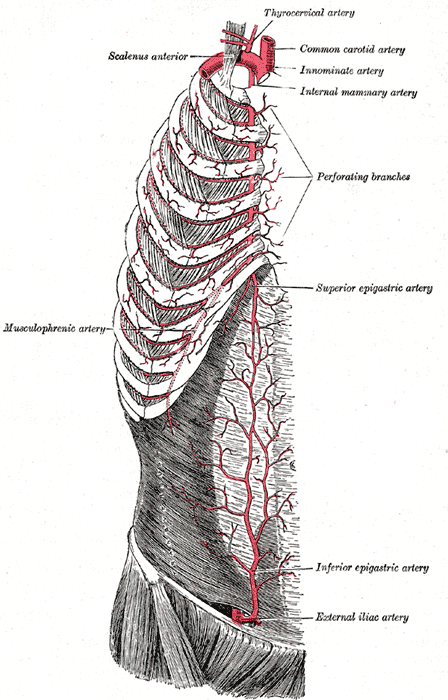

Superiorly, the abdominal wall ultimately receives blood from and drains to tributaries of the subclavian vessels. The internal thoracic artery is a branch of the first part of the subclavian artery. It descends between the internal intercostals and transversus thoracis muscles posterior to the upper six costal cartilages in the thorax. It passes into the abdomen through the sternocostal triangle or foramina of Morgagni at the anterior-most aspect of the diaphragm just behind the sternum. As it enters the abdomen, it gives off the musculophrenic artery and becomes the superior epigastric artery. The musculophrenic travels inferolaterally along the subcostal margin to supply the hypochondrium region and anterolateral diaphragm. The superior epigastric supplies the epigastric and umbilical regions as well as the rectus abdominis muscle, running posterior to it in the rectus sheath. The venous drainage closely follows the arterial supply, except the internal thoracic veins drain into the brachiocephalic veins superiorly.

The lateral abdominal wall and lumbar regions receive vascular supply from branches of the thoracic aorta, including the tenth and eleventh posterior intercostal arteries and the subcostal. They reach the lateral abdomen by traveling circumferentially between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. The tenth and eleventh posterior intercostal and subcostal veins run with the arteries before draining into the azygos vein on the right and hemiazygos vein on the left.

Inferiorly, the anterior abdominal wall is supplied superficially by branches of the femoral artery, and deeply by branches of the external iliac artery. Just before the external iliac descends into the femoral ring, it gives off the inferior epigastric and deep circumflex iliac arteries. The inferior epigastric artery ascends the inner surface of the abdominal wall in the lateral umbilical folds on the deep surface of rectus abdominis to supply the deep suprapubic and umbilical regions. At the arcuate line, it enters the rectus sheath, continuing to run behind rectus abdominis where it anastomoses with the superior epigastric in the umbilical region. The deep circumflex travels along the inner surface of the wall superolaterally, running parallel to the inguinal ligament to supply to deep iliac fossa regions. After emerging from the femoral ring, the femoral artery soon gives the superficial epigastric and superficial circumflex iliac arteries. The superficial epigastric runs a recurrent course around the inguinal ligament, ascending in the subcutaneous tissue to supply the superficial iliac fossa region. The major veins draining the anterior inferior abdominal wall follow the same routes as their arterial counterparts. In the umbilical region, these veins may anastomose with paraumbilical vessels that run from the umbilicus along the ligamentum teres to the portal vein. In cases of severe portal hypertension, these anastomoses may become a site of a portosystemic shunt, becoming engorged and visible on the abdominal surface as the “caput medusae” sign.[4]

An understanding of the anatomy of superficial epigastric and deep epigastric vessels is particularly crucial for surgeons constructing free flaps from the inferior abdominal wall to use in reconstructive surgery.[5]

The posterior abdominal wall receives blood from branches of the abdominal aorta. These include the inferior phrenic arteries which run upwards and laterally towards the diaphragmatic crus to supply the diaphragm and adrenals. There are four paired lumbar arteries that arise from the aorta at the level of L1-L4 and pass laterally through arches of tendinous origins of psoas major, pass quadratus lumborum and continue circumferentially between transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles. The drainage of the lumbar veins is more complicated. The four pairs of lumbar veins that travel with their arterial counterparts connect via ascending lumbar veins that arise from the common iliac veins and ascend on either side of the vertebral bodies. The left ascending lumbar vein joins the left subcostal vein to form the azygos vein. The right ascending lumbar vein joins the right subcostal vein to become the hemiazygos vein. Most lumbar veins communicate with both the IVC directly and the ascending lumbar veins.

Superficial lymphatic drainage of the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the anterolateral abdominal wall gets divided by the transumbilical plane. Superiorly lymph vessels drain into pectoral axillary nodes. Inferiorly they drain into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes. Deep lymphatic drainage of the anterolateral abdominal wall muscles follows the deep blood vessels. Superior drainage follows the superior epigastric vessels to the parasternal lymph nodes. Inferior drainage follows the inferior epigastric vessels to the external iliac lymph nodes. Lateral wall drainage follows the intercostal and subcostal vessels to nodes of the posterior mediastinum. Lymphatic drainage of the posterior wall follows the lumbar vessels to the lateral aortic and retro-aortic nodes. Gastrointestinal tumors and in particular pancreatic cancer may metastasize to the umbilicus, a clinical sign which has been named a “Sister Mary Joseph's nodule.” Theories explaining the route of metastasis include via the lymphatics of the falciform ligament.[6]

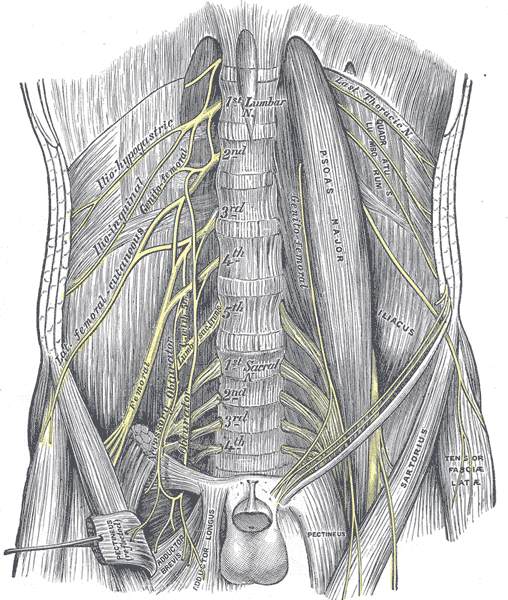

Nerves

Innervation of the muscles of the anterolateral abdominal wall derives primarily from the T7-T12 intercostal nerves. They run a circumferential route anteriorly with the rest of the neurovascular bundle between the layers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis. As the lumbar plexus emerges from the spinal cord, it supplies and runs close to the psoas major and quadratus lumborum muscles of the posterior wall. The iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal branches of the lumbar plexus also supply the lower fibers and conjoint tendon of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles. A “transversus abdominis plane” (TAP) block is an option to provide regional anesthesia of the anterolateral abdominal wall. Infiltration of local anesthetic into the potential space between the internal oblique and transversus abdominis can anesthetize multiple nerves that run in this plane, causing a field block, including branches of nerve roots from T6-L1, for example, the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. There is growing evidence for its application in a range of abdominal surgeries.[7]

Muscles

Anterolateral Abdominal Wall Muscles

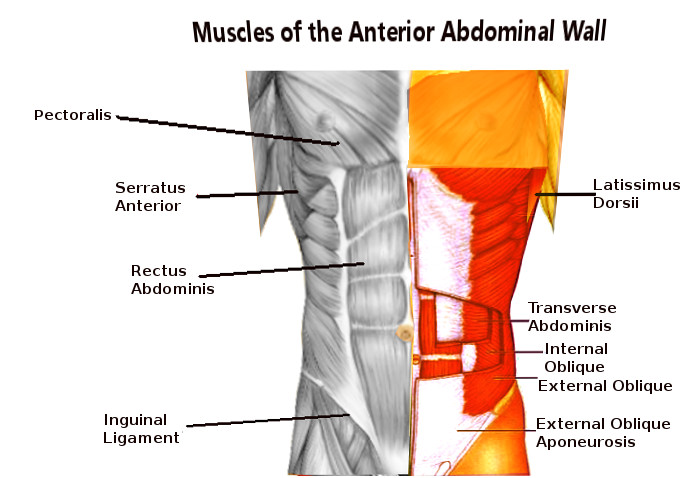

Anterior chest wall strength and movement receive contributions laterally by three layers of large flat paired muscles: the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis. Anteromedially these layers fuse to form a rectus sheath that encloses the rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles. In the midline, the combined aponeuroses of these muscles fuse to form the linea alba.[2]

External Oblique

The external oblique is the most superficial of the anterolateral abdominal wall muscles. Its fibers arise from the fifth through twelfth ribs and run inferomedially. As it approaches the midclavicular line, its fibers form an aponeurotic sheath, which travels superficially across the rectus abdominis to the linea alba in the midline. Together with the internal oblique, contraction causes rotation and lateral flexion of the vertebral column. Its inferior border forms the inguinal ligament, which runs between the ASIS and pubic tubercle.

Internal Oblique

This muscle lies immediately deep to external oblique. Together with the external oblique, contraction causes rotation and lateral flexion of the vertebral column. It originates from the lumbar fascia, iliac crest, and lateral inguinal ligament. Its fibers run superomedially, orthogonal to the external oblique before also becoming aponeurotic. Medially, its contributions to the rectus sheath differ between its upper fibers and lower fibers. Upper fibers divide to enclose the rectus sheath anteriorly and posteriorly. Inferiorly, all fibers travel anterior to the rectus abdominal muscle. This portion of the rectus sheath will be deficient posteriorly, with no aponeurotic layer between the rectus abdominis and the transversalis fascia. The inferior end of the posterior rectus sheath is called the “arcuate line.” Irrespective of their relationship to rectus abdominis, all layers continue medially to join the linea alba in the midline.

Transversus Abdominis

This muscle is the deepest of the anterolateral muscles. It arises from the fifth through tenth costal cartilages, lumbar fascia, iliac crest, and lateral inguinal ligament. Its fibers run transversely before becoming aponeurotic and running into the rectus sheath. Its upper portion travels posteriorly to the rectus abdominal muscles, contributing to the posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, its aponeurosis runs anteriorly to the muscle, contributing to the anterior sheath. The contraction of the transversus abdominis causes compression of abdominal contents. The inferior edge of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis form the conjoint tendon.

Rectus Abdominis

This muscle is long and narrow, running in the rectus sheath vertically and parallel to the linea alba. It arises from the pubic symphysis and crest and runs superiorly to attach to the fifth through seventh costal cartilages. It is a powerful flexor of the vertebral column. Each muscle belly is divided by three tendinous intersections into four discrete muscle segments. The tendinous intersections have a tether to the overlying anterior rectus sheath. In an athlete, these may be visible and described as a ‘six-pack.’[8]

Pyramidalis

This muscle is a minor triangular muscle that sits anteriorly to the rectus abdominis in the inferior rectus sheath. Its origin is from the body of the pubis and tenses the linea alba when contracting. It is present bilaterally in 80% of people.[9]

Posterior Abdominal Wall Muscles

Quadratus Lumborum

This muscle originates from the iliolumbar ligament and iliac crest and runs superomedially to insert into the twelfth rib and L1-4 transverse processes. Contraction can cause lateral flexion and extension of the vertebral column, and depression of the rib cage.

Psoas Major

This muscle originates from the transverse processes of T12 and L1-4 vertebrae and lateral surfaces of the intervening intervertebral discs. It runs inferiorly, joining the iliacus to insert into the lesser trochanter of the femur. Contraction causes flexion of the thigh.

Surgical Considerations

When planning the approach to the abdominal cavity, a surgeon must balance considerations of ease of access to complete the operation against morbidity caused by the approach. Different approaches will have varying consequences in terms of cosmesis, wound healing, and incisional hernias. This balance will depend on the urgency and indication for operation. An emergency exploratory laparotomy will involve a sizeable vertical midline incision to allow quick access and a broad view of the abdominal contents. Elective procedures will involve smaller, carefully planned incisions. Transverse incisions, e.g., the Pfannenstiel incision that runs parallel to Langer’s lines of skin tension, lead to better cosmesis with reduced scarring and increased wound strength. Muscle splitting incisions in line with muscle fibers are preferred to muscle cutting as transection will kill the muscle fibers. Incisions require careful planning to avoid significant motor nerves as denervation and paralysis of abdominal wall musculature will increase the risk of hernias. Laparoscopic surgery is frequently replacing traditional open surgical approaches. Patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery have a lower rate of postoperative wound infections and incisional hernias and have a shorter hospital stay compared with the equivalent open approach.[10]

Clinical Significance

Knowledge of the working anatomy of the abdominal wall is required to understand its pathology and potential for surgical repair. Defects in the abdominal wall will affect its ability to contain abdominal contents, which can manifest clinically as a congenital or acquired hernia – an abnormal protrusion of tissue through an opening.

Congenital hernias may occur due to weak spots in the neonatal abdominal wall or embryological malformations during development. They range from the common, more benign umbilical hernia to life-threatening gastroschisis. Umbilical hernias involve herniation of abdominal contents through a patent umbilical ring after birth. They often spontaneously resolve without the need for surgical intervention.[11] An omphalocele occurs due to malrotation of the abdominal contents causing them to be outside the abdominal wall, covered only by peritoneum. It is often associated with other congenital malformations and may be fatal without appropriate management.[12] In gastroschisis, the intestines lie outside the abdominal wall with no overlying membrane due to a failure of fusion of the lateral body wall folds in embryonic development.[3] This condition is fatal without surgical correction.[3]

Acquired hernias of the abdominal wall occur in areas of weakness and may cause complications, including pain, bowel obstruction, and strangulation. Epigastric hernias typically occur in the midline through the linea alba, above the umbilicus. Acquired umbilical hernias in adults cause more morbidity than their pediatric equivalent and usually require operative intervention. Spigelian hernias occur at the semilunar line demarcating the lateral border of rectus abdominis and the rectus sheath, usually above the arcuate line.[13] Inguinal hernias protrude through the superficial ring of the inguinal canal at the inferior border of the anterolateral muscles.[14] Incisional hernias may occur as a result of any incision postoperatively.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Superficial Arteries of the Chest and Abdomen; Right side, Musculophrenic Artery, Scalenus Anterior, Thyrocervical Artery, Common Carotid Artery, Innominate Artery, Internal Mammary Artery, Perforating Branches, Superior Epigastric Artery, Inferior Epigastric Artery, External Iliac Artery

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Cherla DV, Moses ML, Viso CP, Holihan JL, Flores-Gonzalez JR, Kao LS, Ko TC, Liang MK. Impact of Abdominal Wall Hernias and Repair on Patient Quality of Life. World journal of surgery. 2018 Jan:42(1):19-25. doi: 10.1007/s00268-017-4173-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28828517]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSeeras K, Qasawa RN, Ju R, Prakash S. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Anterolateral Abdominal Wall. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30247850]

Sadler TW, Feldkamp ML. The embryology of body wall closure: relevance to gastroschisis and other ventral body wall defects. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2008 Aug 15:148C(3):180-5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30176. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18655098]

Giambelluca D, Caruana G, Cannella R, Picone D, Midiri M. The "caput medusae" sign in portal hypertension. Abdominal radiology (New York). 2018 Sep:43(9):2535-2536. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1493-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29450607]

Lipa JE. Breast reconstruction with free flaps from the abdominal donor site: TRAM, DIEAP, and SIEA flaps. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2007 Jan:34(1):105-21; abstract vii [PubMed PMID: 17307075]

Yendluri V, Centeno B, Springett GM. Pancreatic cancer presenting as a Sister Mary Joseph's nodule: case report and update of the literature. Pancreas. 2007 Jan:34(1):161-4 [PubMed PMID: 17198200]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsai HC, Yoshida T, Chuang TY, Yang SF, Chang CC, Yao HY, Tai YT, Lin JA, Chen KY. Transversus Abdominis Plane Block: An Updated Review of Anatomy and Techniques. BioMed research international. 2017:2017():8284363. doi: 10.1155/2017/8284363. Epub 2017 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 29226150]

Broyles JM, Schuenke MD, Patel SR, Vail CM, Broyles HV, Dellon AL. Defining the Anatomy of the Tendinous Intersections of the Rectus Abdominis Muscle and Their Clinical Implications in Functional Muscle Neurotization. Annals of plastic surgery. 2018 Jan:80(1):50-53. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001193. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28671887]

Natsis K, Piagkou M, Repousi E, Apostolidis S, Kotsiomitis E, Apostolou K, Skandalakis P. Morphometric variability of pyramidalis muscle and its clinical significance. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2016 Apr:38(3):285-92. doi: 10.1007/s00276-015-1550-4. Epub 2015 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 26364033]

Kössler-Ebs JB, Grummich K, Jensen K, Hüttner FJ, Müller-Stich B, Seiler CM, Knebel P, Büchler MW, Diener MK. Incisional Hernia Rates After Laparoscopic or Open Abdominal Surgery-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World journal of surgery. 2016 Oct:40(10):2319-30. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3520-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27146053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZens T, Nichol PF, Cartmill R, Kohler JE. Management of asymptomatic pediatric umbilical hernias: a systematic review. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 Nov:52(11):1723-1731. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.07.016. Epub 2017 Jul 24 [PubMed PMID: 28778691]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZahouani T, Mendez MD. Omphalocele. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085552]

Huttinger R, Sugumar K, Baltazar-Ford KS. Spigelian Hernia. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30855874]

Tuma F, Lopez RA, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Inguinal Region (Inguinal Canal). StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261933]

![Abdomen Muscles, [SATA]](/pictures/getimagecontent//6473)