Introduction

White blood cells, or leukocytes (Greek; leucko=white and cyte = cell), are part of the immune system, participating in both the innate and humoral immune responses. They circulate in the blood and mount inflammatory and cellular responses to injury or pathogens.

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

Leukocytes can be classified as granulocytes and agranulocytes based on the presence and absence of microscopic granules in their cytoplasm when stained with Giemsa or Leishman stains.

Granulocytes

Neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils are all granulocytes. These cells also all have azurophilic granules (lysosomes) and specific granules that contain substances unique to each cell's function. Histologically, granulocytes can be distinguished from one another by the morphology of their nucleus, their size, and how their granules stain.[1]

Neutrophils are 12 to 15 µm in diameter and have multi-lobed nuclei typically consisting of 3 to 5 segments joined by thin strands or isthmuses. Thus, they are also called polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Neutrophils contain specific granules in the cytoplasm that cannot be resolved by light microscopy and, therefore, give the cytoplasm a pale pink color. Neutrophils, when activated, migrate into the tissues via diapedesis. These cells have life spans of a few days, and when activated in connective tissue, undergo apoptosis and are then removed by macrophages.

Eosinophils have a bi-lobed nucleus with large cytoplasmic specific granules that are eosinophilic, staining red to pink.

Basophils are 12 to15 µm in diameter, have bi-lobed or S-shaped nuclei, and contain cytoplasmic specific granules (0.5 µm) in diameter that stain blue to purple. The basophilia of the granules is due to the presence of heparin and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. These cells have similar functions as mast cells.

Agranulocytes

Agranulocytes consist of lymphocytes and monocytes, and while they lack specific granules, they do contain azurophilic granules.

Monocytes are precursor cells for the mononuclear phagocytic system, which include cells such as macrophages, osteoclasts, and microglial cells in connective tissue and organs. These cells constitute 4 to 8% of white blood cells, are 12 to 15 µm in diameter, and have large nuclei that are indented or C- C-shaped, which can be eccentric. There is abundant cytoplasm, and the lysosomal granules at the resolution of the light microscope give the cytoplasm a bluish-gray color.

Lymphocytes constitute approximately 25% of white blood cells, are of varying sizes, and have spherical nuclei. The small lymphocytes are similar in size to red blood cells, have spherical heterochromatic nuclei, and scant cytoplasm. Larger lymphocytes, such as activated lymphocytes, have indented nuclei and are 9 to 18 µm in diameter with more cytoplasm containing azurophilic granules. Lymphocytes subdivide into several groups using the cluster of differentiation (CD) markers. The major groups are B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes.

Function

All white blood cells or leukocytes are involved in immune system function; however, the specific roles and functions vary for each blood cell type.

Diapedesis (also called Extravasation or Leukocyte Adhesion Cascade)

Leukocyte migration to sites of injury or infection is mediated by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) present on microbes and damaged tissue, respectively. Local inflammatory cells, such as macrophages and mast cells, detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and release cytokines as a signal for leukocytes to migrate out of circulation. Histamine and heparin released by perivascular mast cells aid in opening intracellular junctions between the capillary endothelial cells. Furthermore, endothelial cells secrete chemoattractants and express surface markers, including selectins, integrin, and cellular adhesion molecules (CAMs) on their lumen that cause leukocyte adhesion, rolling, arrest, and eventual migration into the affected tissues.

Myeloid

Myeloid cells include the leukocytes (granulocytes, monocytes) as well as erythrocytic (red blood cell) lineages but do not include the lymphoid cell lineages.

Neutrophils comprise 50% to 70% of circulating leukocytes and represent the body's initial line of defense. They are involved in the acute inflammatory response to bacterial infection and the removal of the bacteria by phagocytosis. They are also the most numerous cells to arrive at the site of injury or infection. There, they undergo diapedesis to the site of infection or injury. They then recognize foreign antigens on bacteria, infectious agents, dead cells, and debris via a variety of membrane receptors. These are then phagocytosed and degraded by enzymes within intracellular phagolysosomes. Specific and azurophilic granules containing myeloperoxidase fuse with the lysosome, with respiratory bursts resulting in the generation of reactive oxygen species and degradation of bacteria within the phagolysosomes.

Basophils have similar functions to mast cells and supplement their activity. They make up less than 1% of all leukocytes. Their primary function is inflammation and allergic reaction. Basophils have a high affinity for binding IgE antibodies on their surface. Antigens (allergens) binding to the IgE on the basophil surface results in degranulation and release of substances such as mediators of inflammation like histamine, eosinophil chemotactic factor, platelet-activating factor, and phospholipase A.[2][3] These agents cause the symptoms of allergies and, in extreme cases, hypersensitivity reactions and anaphylaxis. Of note, basophils have almost no phagocytic abilities.

Eosinophils make up about 1 to 4% of the leukocytes on average. They are involved in chronic inflammation, allergic reactions, and host deference against parasitic infections. They also modulate potentially deleterious effects of inflammatory vasoactive mediators. This modulatory effect is via specific substances, arylsulfatase and histaminase, enzymes that decompose leukotrienes and histamine, respectively. Eosinophils combat parasitic infections by releasing their specific granules, of which the cationic protein, a major basic protein, has toxicity against helminth parasites.[4] Last, like neutrophils and basophils, eosinophils are phagocytic; however, they commonly clear antigen-antibody complexes.

Monocytes make up between 2% to 8% of leukocytes. They differentiate and only become functional once they leave the blood. Once in the tissues, they differentiate into cells of the mononuclear phagocytic system, such as macrophages (in the lung, connective tissue and lymphatic tissues, and bone), osteoclasts, and Kupffer cells. There, they phagocytose bacteria, cells, and debris and function as antigen-presenting cells.

Lymphoid

Lymphocytes are agranulocytes, consisting of 20% to 40% of the leukocyte counts, and are part of the adaptive immune system. Lymphocytes are circulating immunocompetent cells, cells that develop the ability to recognize and react to antigens and are in transit from and to various lymphatic tissues.

Tissue Preparation

Blood smear slides are most often visualized with Giemsa or Leishman's stains, which allows for the coloration of cell contents and granules as basophilic (blue) or eosinophilic (red) and the subsequent histological identification of the different leukocytes.

Microscopy, Light

Neutrophilic specific granules are barely resolvable by light microscopy, whereas those of eosinophils and basophils are larger and stain red/pink and purple/blue, respectively.[5]

Microscopy, Electron

The ultrastructure of granulocytes is characterized by the abundance of the granules in the cytoplasm. Azurophilic granules are present in all granulocytes and also in monocytes and lymphocytes. The neutrophil-specific granules are smaller, less electron-dense, more numerous, and rounded than the azurophilic granules. The specific granules of the eosinophils are oval, electron-dense, characterized by having a central crystalloid formed of major basic protein.[5] The basophils have larger and irregularly shaped granules, which are less in number.[6]

Clinical Significance

Labs

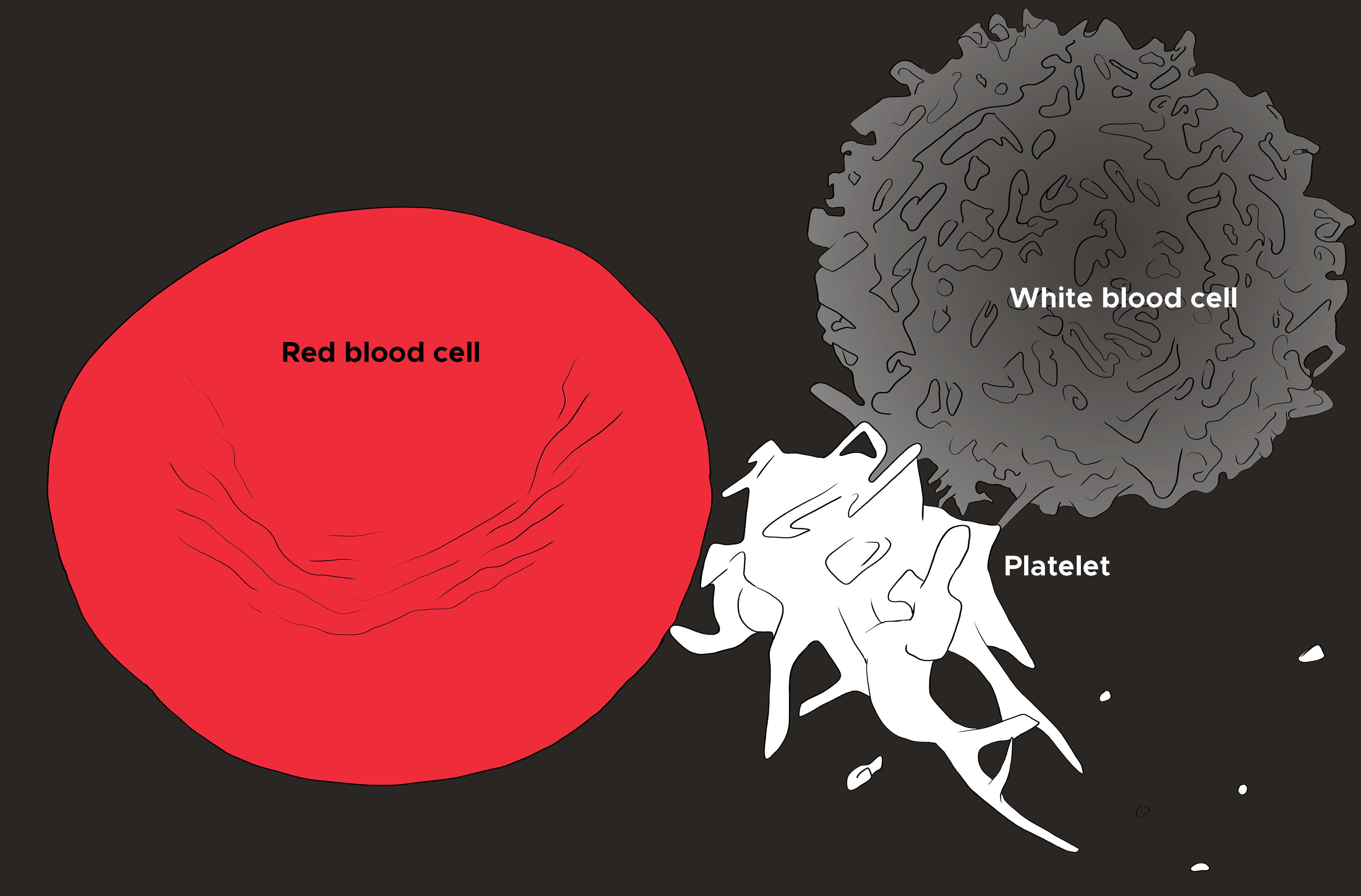

Clinically, the complete blood count (CBC) test measures leukocytes. A CBC is frequently ordered to provide insight into disease processes and includes measurements of the leukocytes, as well as red blood cell and platelet totals (see Illustration. Illustration of Red Blood Cell, Platelet, and White Blood Cell). Often associated with the CBC is a differential, which refers to the relative amounts of white blood cell types (i.e., neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, etc.) as a percentage of the total number of WBCs. Of note, if a subtype of white blood cells seems to be elevated based on the differential, the actual value of the type of white blood cells should be calculated by multiplying the percentage listed on the differential by the total number of white blood cells.

The normal range of values for white blood cells is 4,000 to 11,000/µL. Anything below this range is leukopenia, and anything that exceeds this range qualifies as leukocytosis.

A peripheral blood smear is an additional optional test that allows for the histological analysis of the peripheral blood. This test is particularly helpful in cases of leukopenia or if there is a concern for leukemia or lymphoma.

Leukopenia

This condition is where the leukocyte counts are lower than normal. Leukopenia can occur with viral infections and other conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

Leukocytosis

This condition is where the leukocyte counts (primarily neutrophils) are higher than normal, accompanied by a “left shift” or an increase in immature cells in the blood. Leukocytosis is commonly a sign of inflammatory response such as infection, but can also occur during parasitic infections or cancers such as leukemia. Neutrophils can also become elevated due to other conditions, such as stress.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Prinyakupt J, Pluempitiwiriyawej C. Segmentation of white blood cells and comparison of cell morphology by linear and naïve Bayes classifiers. Biomedical engineering online. 2015 Jun 30:14():63. doi: 10.1186/s12938-015-0037-1. Epub 2015 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 26123131]

Karasuyama H, Obata K, Wada T, Tsujimura Y, Mukai K. Newly appreciated roles for basophils in allergy and protective immunity. Allergy. 2011 Sep:66(9):1133-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02613.x. Epub 2011 May 5 [PubMed PMID: 21545430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorriello F, Iannone R, Marone G. Histamine Release from Mast Cells and Basophils. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2017:241():121-139. doi: 10.1007/164_2017_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28332048]

Kita H. Eosinophils: multifaceted biological properties and roles in health and disease. Immunological reviews. 2011 Jul:242(1):161-77. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01026.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21682744]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMelo RC, Dvorak AM, Weller PF. Contributions of electron microscopy to understand secretion of immune mediators by human eosinophils. Microscopy and microanalysis : the official journal of Microscopy Society of America, Microbeam Analysis Society, Microscopical Society of Canada. 2010 Dec:16(6):653-60. doi: 10.1017/S1431927610093864. Epub 2010 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 20875166]

Woessner S. Transmission electron microscopy in hematological diagnosis. Ultrastructural pathology. 2005 May-Aug:29(3-4):237-68 [PubMed PMID: 16036879]