Introduction

The third cranial nerve is also known as oculomotor nerve and has 2 major components:

- Outer parasympathetic fibers that supply the ciliary muscles and the sphincter pupillae

- Inner somatic fibers that supply the levator palpebrae superioris in the eyelid (which retracts the upper eyelid) and the 4 extraocular muscles (superior, middle, inferior recti, and inferior oblique).

LR6(SO4)3 is a simple mnemonic representing the innervation of the extraocular muscles. It stands for:

- LR6: Lateral rectus muscle which is supplied by the sixth cranial nerve

- SO4: Superior oblique muscle which is supplied by the fourth cranial nerve

- 3: The third cranial nerve supplies other extraocular muscles

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Third-Nerve Palsy (TNP) Causes

- Vascular ischemia

- Trauma

- Intracranial neoplasm

- Hemorrhage

- Congenital

- Idiopathic

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension cause ischemic changes in the nerve and are the most common systemic causes of acquired nerve palsy.[1]

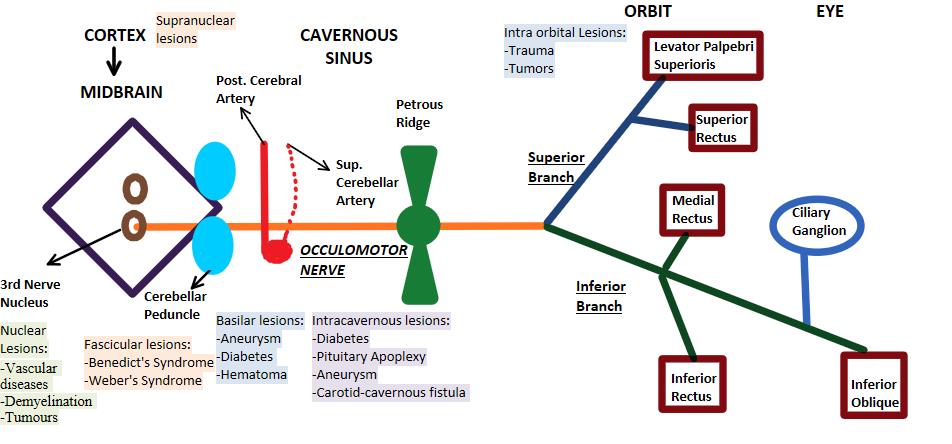

The etiology and presentation of acquired third-nerve lesions at various levels are different[2]:

- Supranuclear lesions: Lesions at the level of the cerebral cortex or the supranuclear pathway cause conjugate paresis of both the eyes.

- Nuclear lesions: Vascular diseases, demyelination, and tumors are the main cause of third-nerve palsy.

- Fascicular lesions: The etiology is similar to the nuclear lesions.

- Basilar portion: In this region, isolated third-nerve palsy is very common. The primary causes of isolated palsy include aneurysms, diabetes mellitus,[3], and extradural hematoma. Third-nerve palsy from a posterior communicating artery, posterior cerebral artery, or superior cerebellar artery aneurysm has been recorded.[4] The palsy results from either direct compression of the nerve by an aneurysm or due to subarachnoid hemorrhage in the vicinity of an aneurysm.[4] This causes isolated and painful third-nerve palsy. Extradural hematoma results in tentorial pressure cone and herniation of the temporal lobe. The third nerve gets compressed by the herniation as it passes over the tentorial edge, leading to third-nerve palsy.

- Intracavernous portion: As there are other nerves present in the vicinity of the third-nerve, any lesion in the cavernous sinus will result in multiple nerve palsies of the cranial nerve IV, cranial nerve VI, and the first division of cranial nerve V. The common etiology is diabetes, pituitary apoplexy, aneurysm, or carotid-cavernous fistula.

- Intraorbital portion: Trauma, tumors, and Tolosa-Hunt syndrome are the main causes of intraorbital third-nerve palsy.

Third-Nerve Palsy in Children

All acquired third-nerve palsy cases should be investigated thoroughly to exclude any space-occupying lesion. Other common causes include[2]:

- Congenital: 43%

- Local inflammation: 13%

- Trauma: 20%

- Aneurysm: 7%

- Myasthenia gravis

- Migraine

Also, all pediatric patients with strabismus should be checked for uncorrected refractive error after administering cycloplegics.[5]

Congenital causes: Development aplasia or hypoplasia of the oculomotor nucleus, birth trauma due to molding forces acting on the skull during labor, intrauterine trauma, and rarely infections such as meningitis.

Epidemiology

third-nerve palsy is an important sign of life-threatening aneurysms. Keane et al. studied the causes of TN and found the incidence of aneurysm to be 10%,[6] and bilateral cases were seen in 11% of patients. The incidence of third-nerve palsy in females and males is not significantly different[7]; whereas, it is less frequent in children and young adults. The age group maximally affected by third-nerve palsy is more than 60 years as recorded by Chengbo et al.[7] Pupil involvement was seen in 43% of patients on presentation, however, 86% of patients presented with ptosis on the first visit. The incidence of acquired third-nerve palsy in the US population-based survey by Chengbo et al. was noted to be 4.0 per 100 000.[7]

Pathophysiology

The oculomotor nucleus complex present in the midbrain, at the level of the superior colliculus, consist of:

- Main motor nucleus

- Accessory parasympathetic nucleus (Edinger-Westphal nucleus)

As shown in the figure below, fibers pass through the interpeduncular fossa before passing between the posterior cerebral artery and the superior cerebellar artery to reach the cavernous sinus. During this course, the oculomotor nerve lies lateral to the posterior communicating artery. The nerve then divides into a superior and inferior division and enters the orbit through the superior orbital fissure.[8] In the orbit, the smaller superior division supplies the superior rectus and the levator palpebrae superioris, whereas the larger inferior division supplies the medial rectus, the inferior rectus, and the inferior oblique. An interesting point to note is that before the 3 nerve reaches the orbit, the fibers innervating the pupillary muscles (pupillomotor fibers) are located superficially in the nerve trunk. The pial blood vessels supply these fibers. In contrast, the main trunk of the fibers is supplied by the vasa vasorum.

Lesions such as an aneurysm, uncal herniation, or tumor, which compress the nerve from outside will involve the superficial pupillomotor fibers and their blood supply. On the other hand, medical lesion such as diabetes mellitus or hypertension microangiopathy will affect the vasa vasorum and thus spare the pupillary fibers. This results in pupil-sparing third nerve palsy.[9] Aberrant regeneration of third-nerve may follow compressive or traumatic lesions but not vascular lesions like diabetes. This is because of the endoneurial sheath which is damaged only by compression and trauma and not by vascular lesions. This aberrant regeneration phenomenon can cause lid gaze dyskinesis or pupil-gaze dyskinesis.

History and Physical

Clinical Features

- Ptosis: Due to paralysis of LPS (levator palpebrae superioris) muscle[10]

- Ocular deviation: In case of third-nerve palsy, the lateral rectus and superior oblique are spared, and their unopposed action brings the eye in a “down and out” position.

- Pupil: In compressive third-nerve palsy, the pupil becomes fixed and dilated due to paralysis of sphincter pupillae. Ciliary muscle paralysis also leads to loss of accommodation. However, in ischemic lesions, the pupil is spared, and there is no loss of accommodation.

- Diplopia: This occurs due deviation of the affected eye resulting in the image falling on an extrafoveal point. However, due to ptosis the patient usually doesn’t complain of double vision as ptosis acts as a barrier to diplopia.

Four Distinct Syndromes

- Benedikt syndrome: Ipsilateral third-nerve palsy and contralateral tremors

- Weber syndrome: Ipsilateral third-nerve palsy and contralateral hemiplegia

- Nothnagel syndrome: Ipsilateral third-nerve palsy and cerebellar ataxia

- Claude syndrome: Combined features of both Benedikt and Nothnagel syndromes

Evaluation

Investigations

Patients with pupil-sparing third-nerve palsy should be evaluated to exclude any vascular cause. Lab workup includes blood pressure recording, complete blood count (CBC), blood sugar including Hb1AC and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

If the palsy is non-pupil-sparing, prompt neuro-ophthalmic evaluation should be undertaken. MRI is a more sensitive imaging modality for detecting intracranial anomaly than CT scan.[3] Cranial nerve imaging is usually done by MRI using thin-section (0.7-mm sections) T2-weighted imaging in the axial plane at the level of the brainstem.[11] This shows the nerve as a dark linear image in contrast to the high intensity of the signal from the surrounding cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).[11] CT angiography should be urgently performed if clinical examination suggests an aneurysm.

Treatment / Management

Conservative Treatment

It is advocated as a short-term measure in acute palsy and for patients who are over 50 years of age having a history of diabetes or hypertension.[2] Patients should be followed up every 3 months to check for signs of improvement. Most patients with ischemic third-nerve palsy demonstrate improvement within 1 month and complete recovery in 3 months. In cases of diplopia, the affected eye can be occluded with the help of an eye patch or opaque contact lens.[2] In pediatric cases, amblyopia due to ptosis or squint can be prevented by alternate patching. Talebnejad et al. documented botulinum toxin injection in lateral rectus (LR) in the acute phase of partial third-nerve palsy.[12] Botulinum toxin causes paralysis of the LR, and subsequently, the outward deviation of the eye is neutralized in the primary position.

Surgical Treatment

In pupil-sparing cases, surgical treatment is advised after 6 months in acquired palsies, if there is no improvement in symptoms. Surgery for third-nerve palsy is nevertheless challenging, and the goals are to provide alignment of the eye in primary gaze and to provide binocular single vision. Before operating on the lid to correct ptosis, the eye should be aligned to prevent diplopia. Surgical options for TNP depend on the degree of the palsy: complete or partial. Surgery for complete third-nerve palsy includes resection of the medial rectus and recession of the lateral rectus muscle for correction of horizontal deviation.[13] This may be combined with superior oblique (SO) tendon transposition, which causes a tonic adducting force to the globe to keep it in the primary position.[2] In patients with partial third-nerve palsy, surgery depends on the extent of involvement of extraocular muscles[2]. After the paralytic strabismus is treated, the ptosis can be corrected. Pupil involving third-nerve palsy should be investigated thoroughly and referred to a neurologist.[14](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

- Ophthalmoplegic migraine[15]

- Internuclear ophthalmoplegia

- Ptosis in adults or congenital ptosis

- Anisocoria

- Myasthenia gravis

- Thyroid ophthalmopathy

Prognosis

The prognosis in most cases of third-nerve palsy is usually good, as spontaneous regression of the symptoms occurs within a few months; however, the degree of recovery depends on the etiology and management.[1]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Cosmetic, as well as functional outcome, should be kept in mind while formulating treatment strategies. Surgical treatment is often required in case of complete oculomotor palsy. The surgery often results in a cosmetically acceptable alignment of the eyes.[16] Patients with incomplete third cranial nerve paralysis may also have good functional and cosmetic outcomes with strabismus surgery.[8] Physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and nurses should work as a team to coordinate the care of the patient and the education of the patient and family. (Level V)

Media

References

Kim K, Noh SR, Kang MS, Jin KH. Clinical Course and Prognostic Factors of Acquired Third, Fourth, and Sixth Cranial Nerve Palsy in Korean Patients. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2018 Jun:32(3):221-227. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0051. Epub 2018 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 29770635]

Singh A, Bahuguna C, Nagpal R, Kumar B. Surgical management of third nerve palsy. Oman journal of ophthalmology. 2016 May-Aug:9(2):80-6. doi: 10.4103/0974-620X.184509. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27433033]

Tamhankar MA, Biousse V, Ying GS, Prasad S, Subramanian PS, Lee MS, Eggenberger E, Moss HE, Pineles S, Bennett J, Osborne B, Volpe NJ, Liu GT, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Galetta SL, Balcer LJ. Isolated third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies from presumed microvascular versus other causes: a prospective study. Ophthalmology. 2013 Nov:120(11):2264-9. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.04.009. Epub 2013 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 23747163]

Chaudhry NS, Brunozzi D, Shakur SF, Charbel FT, Alaraj A. Ruptured posterior cerebral artery aneurysm presenting with a contralateral cranial nerve III palsy: A case report. Surgical neurology international. 2018:9():52. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_430_17. Epub 2018 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 29576903]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlswaina N, Elkhamary SM, Shammari MA, Khan AO. Ophthalmic Features of Outpatient Children Diagnosed with Intracranial Space-Occupying Lesions by Ophthalmologists. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 2015 Jul-Sep:22(3):327-30. doi: 10.4103/0974-9233.159739. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26180471]

Keane JR. Third nerve palsy: analysis of 1400 personally-examined inpatients. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2010 Sep:37(5):662-70 [PubMed PMID: 21059515]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFang C, Leavitt JA, Hodge DO, Holmes JM, Mohney BG, Chen JJ. Incidence and Etiologies of Acquired Third Nerve Palsy Using a Population-Based Method. JAMA ophthalmology. 2017 Jan 1:135(1):23-28. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2016.4456. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27893002]

Flanders M, Hasan J, Al-Mujaini A. Partial third cranial nerve palsy: clinical characteristics and surgical management. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2012 Jun:47(3):321-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2012.03.030. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22687316]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMotoyama Y, Nonaka J, Hironaka Y, Park YS, Nakase H. Pupil-sparing oculomotor nerve palsy caused by upward compression of a large posterior communicating artery aneurysm. Case report. Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 2012:52(4):202-5 [PubMed PMID: 22522330]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKomurcu HF, Ayberk G, Ozveren MF, Anlar O. Pituitary adenoma apoplexy presenting with bilateral third nerve palsy and bilateral proptosis: a case report. Medical principles and practice : international journal of the Kuwait University, Health Science Centre. 2012:21(3):285-7. doi: 10.1159/000334783. Epub 2011 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 22156441]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim JH, Hwang JM. Imaging of Cranial Nerves III, IV, VI in Congenital Cranial Dysinnervation Disorders. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2017 Jun:31(3):183-193. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0024. Epub 2017 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 28534340]

Talebnejad MR, Sharifi M, Nowroozzadeh MH. The role of Botulinum toxin in management of acute traumatic third-nerve palsy. Journal of AAPOS : the official publication of the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 2008 Oct:12(5):510-3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2008.03.009. Epub 2008 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 18558505]

Kattleman B, Flanders M, Wise J. Supramaximal horizontal rectus surgery in the management of third and sixth nerve palsy. Canadian journal of ophthalmology. Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 1986 Oct:21(6):227-30 [PubMed PMID: 3779510]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang WX, Xu BN, Wang FY, Wu C, Sun ZH. Microsurgical management of posterior cerebral artery aneurysms: A report of thirty cases in modern era. British journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Jun:29(3):406-12. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1004301. Epub 2015 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 25697238]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDe Silva DA, Siow HC. A case report of ophthalmoplegic migraine: a differential diagnosis of third nerve palsy. Cephalalgia : an international journal of headache. 2005 Oct:25(10):827-30 [PubMed PMID: 16162261]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchumacher-Feero LA,Yoo KW,Solari FM,Biglan AW, Third cranial nerve palsy in children. American journal of ophthalmology. 1999 Aug [PubMed PMID: 10458179]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence