Introduction

The sense of taste, or gustation, permits us to differentiate enjoyable from unpleasant food. Enjoyable food could be the food tasting sweet, salty, sour or savory (umami in Japanese), while unpleasant food has a bitter taste.[1] In recent times, fatty acids and calcium have been considered to be possible tastants sensed by the taste buds.[2] By discovering these basic types of tastes, our taste buds found in the oral cavity act as the gateway chemoreceptors that help us in making our decision whether to permit the food already present in the mouth to get in our body or not.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

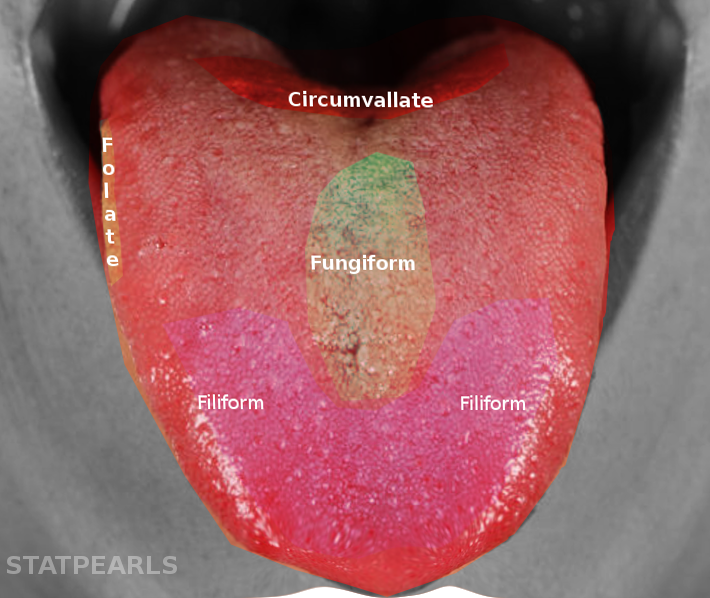

The organization of taste is by multicellular taste buds found predominantly on the tongue and palate. To a lesser extent, they also exist in the other regions of the oral cavity. The taste buds are a group of neuroepithelial receptor cells that are rapidly regenerated, with an average life span of 8 to 12 days; however, some taste buds cells can remain for much longer. The molecular features of taste buds can differ among individuals. There are three types of taste buds papillae[1][2][3]:

- Fungiform taste buds papillae: They are mushroom-shaped and located in the anterior two-thirds of the tongue

- Circumvallate taste buds papillae: They are inverted V-shaped, larger and more complex, and are located in the posterior one-third of the tongue

- Foliate taste buds papillae: Their location is on the lateral sides of the tongue

These taste buds own functional properties similar to neurons; they transduce taste stimuli into electrical signals, then transfer these signals to the sensory nerves.[1]

There are five identified distinct cell types of taste buds cells, type I cells, receptor (type II) cells, presynaptic (type III) cells, basal cells, and neuronal processes. Type I cells are glial-like cells. Type II cells express G protein-coupled taste receptors for bitter, sweet and savory taste types, and secrete adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and acetylcholine (ACh) neurotransmitters. While type III cells sense the sour taste and secrete serotonin (5-hydroxytrptamine/5-HT), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and norepinephrine neurotransmitters. Cells that transduce salty taste have not been yet definitely discovered in terms of these types of taste cells.[3][4]

The filiform papillae are the non-taste papillae of the tongue. They constitute the tough surface of the tongue and are considered to be the bulk of the tongue papillae.

Embryology

It's clear that the appearance of innervation takes places before the taste buds develop, as the gustatory axons appear first at the seventh gestational week, followed later by the development and maturation of the taste buds papillae at weeks 10 to 13 of gestation, as innervated, differentiated, and presumably functional.[2][5]

During gestation, taste stimuli enter the amniotic fluid, that the fetus continuously swallows, and after birth, research shows that tastes of the maternal diet are apparent in breast milk. The dietary preferences of children are profoundly affected by this exposure, as they explore these new tastes.[2]

Nerves

Generally, taste buds (fungiform, circumvallate and foliate papillae) are innervated by sensory neurons of the 7th (facial) and 9th (glossopharyngeal) cranial nerves ganglia, whose axons transfer taste input from peripheral taste buds to the hindbrain.[1] The anterior fungiform papillae receive innervation by the chorda tympani branch of the 7th cranial nerve; the posterior circumvallate papillae are innervated by the 9th cranial nerve, while the foliate papillae receive innervation from both the 7th and 9th cranial nerves. The greater superficial petrosal nerve (also a branch of the 7th cranial nerve) innervates the taste buds located in the palate.[4]

The 5th (trigeminal) cranial nerve receives input from the non-taste filiform papillae.[3]

Physiologic Variants

The theory of having only four or five types of tastes has been debatable in the domain of gustation. Some of the gustation researchers have argued that there's no real rationale to test these basic tastes and thus it was never tested. As a result, those researchers suggested that there may be fine distinctions and differences in the perceptual quality in the taste classifications, making them not only four or five taste types, but rather a variety of different taste forms.[6]

Clinical Significance

Taste disorders are categorized as ageusia (total loss of taste), hypogeusia (decreased sense of taste), and hypergeusia (increased taste sensitivity).[7]

Aguesia is rarely seen and is attributed to the redundant gustatory nerve supply of the tongue.[8]

Taste dysfunction is common in disease and injury[1]; it decreases the patient's quality of life and causes anorexia, malnutrition, and weight loss. The most common conditions to cause taste dysfunctions are viral upper respiratory tract infections and infections of the oral cavity. Other diseases frequently associated with taste abnormalities include influenza-like illness, AIDS and autoimmune diseases such as Sjogren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, and inflammatory bowel disease. Furthermore, taste dysfunction can happen as a sequel to cancer chemotherapy, as well as after radiotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Approximately two-thirds of cancer patients treated by chemotherapy reported having taste abnormalities that may last for months after the treatment.[9]

Taste dysfunction in cancer patients is found to correlate with decreased oral intake and poorer prognosis; this may be because of the rapid growth of cancer cells along with the inflammation and tissue damage.

Disorders that affect the central or peripheral nervous system also alter the taste, as well as neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. Moreover, injury to the chorda tympani nerve during ear surgery may cause impairment of taste.

There are reports of taste along with smell hallucination in some patients with epilepsy and schizophrenia.[8]

Taste sense generally declines with aging; the effects of aging differ among the various taste qualities, however, mostly it affects the salty and bitter tastes. Although it is very common to have taste abnormalities in elderly patients, it is underreported in this population.[9]

Dysgeusia

Dysgeusia is a taste disorder characterized by a disruption in taste sensation or the presence of taste in the absence of stimuli. It is the most common taste abnormality reported by patients. Common etiologies of dysgeusia include local factors such as oral cavity infections, medications, systemic diseases, central or peripheral nervous system disorders.[7] Sometimes sweet dysgeusia may be the first presenting sign of lung tumors.[8] Although it's rare, dysgeusia can also occur in cases of vestibular schwannomas as the presenting symptom.[10] In many cases, the cause of dysgeusia remains unidentified and thus it is diagnosed as idiopathic oral dysgeusia.[7]

Patient Examination

Examination of a patient with taste disorder includes the examination of the oral cavity and the ears. Patient's dental hygiene and flow of saliva should also be a consideration. The patient should be asked about any pain in the oral cavity, swelling, change in chewing behavior, ear infection, and associated diseases.[8] Any history related to previous ear surgeries that could damage the chorda tympani nerve also merit consideration.

Testing the Ability to Taste

Testing the tasting ability can be done by offering liquid stimuli or taste strips to the anterior and posterior part of the tongue. Other tests include electrogustometry (which involves passing anodal current to the tongue to generate a taste perception) and gustatory evoked potentials. Imaging also could be used to rule in or rule out central nervous system damage. Swab tests and cultures can also be helpful in diagnosis if a bacterial or mycological infection is suspected.[8]

Treatment of Taste Disorders

The main approach in treating disorders of the taste is to address the underlying disease causing this disturbance. Zinc sulfate, steroids, and vitamin A are the frequently used medications despite the conflicts in clinical research results. Therefore, researchers need to conduct further studies on the treatment of gustatory disorders.[7]

Media

References

Barlow LA. Progress and renewal in gustation: new insights into taste bud development. Development (Cambridge, England). 2015 Nov 1:142(21):3620-9. doi: 10.1242/dev.120394. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26534983]

Barlow LA, Klein OD. Developing and regenerating a sense of taste. Current topics in developmental biology. 2015:111():401-19. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2014.11.012. Epub 2015 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 25662267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGravina SA, Yep GL, Khan M. Human biology of taste. Annals of Saudi medicine. 2013 May-Jun:33(3):217-22. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2013.217. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23793421]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoper SD. Taste buds as peripheral chemosensory processors. Seminars in cell & developmental biology. 2013 Jan:24(1):71-9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.12.002. Epub 2012 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 23261954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOakley B, Witt M. Building sensory receptors on the tongue. Journal of neurocytology. 2004 Dec:33(6):631-46 [PubMed PMID: 16217619]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceErickson RP. A study of the science of taste: on the origins and influence of the core ideas. The Behavioral and brain sciences. 2008 Feb:31(1):59-75; discussion 75-105. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08003348. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18394244]

Heckmann JG, Heckmann SM, Lang CJ, Hummel T. Neurological aspects of taste disorders. Archives of neurology. 2003 May:60(5):667-71 [PubMed PMID: 12756129]

Hummel T, Landis BN, Hüttenbrink KB. Smell and taste disorders. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2011:10():Doc04. doi: 10.3205/cto000077. Epub 2012 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 22558054]

Feng P, Huang L, Wang H. Taste bud homeostasis in health, disease, and aging. Chemical senses. 2014 Jan:39(1):3-16. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt059. Epub 2013 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 24287552]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBrown E, Staines K. Vestibular Schwannoma Presenting as Oral Dysgeusia: An Easily Missed Diagnosis. Case reports in dentistry. 2016:2016():7081919. doi: 10.1155/2016/7081919. Epub 2016 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 27022490]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence