Introduction

Syphilis is a systemic bacterial infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. Due to its many protean clinical manifestations, it has been named the "great imitator and mimicker." The origin of syphilis has been controversial and under great debate, and many theories have been postulated regarding this.

The Columbian theory is the most accepted and postulates that syphilis came to Europe in the 1490s when Columbus arrived in Italy from America. After Italy surrendered to the invading French in 1495, this new disease rapidly spread across Europe.[1] The name "syphilis" comes from the work of Girolamo Fracastoro, a noted poet and physician in Verona, Italy. In 1530, he wrote about a shepherd named Syphilus who angered Apollo, causing the god to curse the entire population with the affliction that we now know as syphilis.[2][3]

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted disease (STD), and humans are its only host. Treponema bacteria are susceptible to heat, cold, and oxygen exposure, so they do not survive long outside the human body. An initial inoculation with as few as 500 to 1000 bacterial organisms is sufficient for an individual to become infected. The incubation period of syphilis is roughly 3 to 4 weeks and is inversely proportional to the number of inoculated organisms.

The Wasserman test, the first reliable test for syphilis, was developed in 1906.[4] This nontreponemal complement fixation test has since been replaced by newer nontreponemal assays (such as venereal disease research laboratory [VDRL] and rapid plasma reagin [RPR]), which are more reliable.[5]

The untreated infection progresses through 4 stages (primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary) and can affect multiple organ systems, often many years or even decades after the original infection. Syphilis prevalence peaked in 1947, just before the widespread introduction of penicillin, which caused rates to plummet, but recent trends have shown exponentially rising rates.[6]

Today, syphilis remains a contemporary plague that continues to afflict millions of people worldwide, and its incidence is increasing.[7] Its association with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) significantly worsens the prognosis and is so prevalent that patients who test positive for either infection should be routinely tested for the other.[8][9][10] The cornerstone of eradicating and controlling the disease is early appropriate testing using serologic blood screening with efficient, inexpensive, and widely available nontreponemal tests (VDRL and RPR). Confirmatory testing with a more complex treponemal-specific antibody assay (FTA-ABS, TPPA, and TPHA) is necessary to confirm the diagnosis.[11][12]

As the clinical manifestations are so varied, clinicians must be constantly aware of the possibility of syphilis in the differential diagnosis of symptoms affecting virtually any bodily organ system and perform appropriate screening serologic testing. Fortunately, the causative organism is still very sensitive to penicillin, but despite this, syphilis remains a major modern global public health challenge as testing and treatment efforts so far have been insufficient to halt its progression and increasing prevalence.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The Treponema genus is a spiral-shaped bacteria with a rich outer phospholipid membrane that belongs to the spirochetal order. It has a slow metabolic rate, taking an average of 30 hours to multiply. T pallidum is the only treponemal agent that causes venereal disease. The other Treponema subspecies are responsible for various non-venereal diseases that are transmitted via nonsexual contact: Treponema pertenue causes yaws, Treponema pallidum endemicum produces endemic syphilis or bejel, and Treponema carateum results in pinta. All the treponemal bacteria have similar DNA but differ in geographical distribution and pathogenesis.[13] Humans are the only hosts for the organisms, and there is no animal reservoir.

Syphilis is considered an STD, as most cases are transmitted through vaginal, anogenital, and orogenital contact. The infection can rarely be acquired via nonsexual contacts, such as skin-to-skin or direct transfer (blood transfusion or needle sharing). Vertical transmission occurs transplacentally, resulting in congenital syphilis.

Epidemiology

The 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study indicated a worldwide prevalence of about 50 million syphilis cases, representing an alarming 60% overall increase from 1990 to 2019.[14] The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 7.1 million cases in 2020, with the highest incidence in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean.[15][16]

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) statistics, the incidence of syphilis among adults in the US increased by 38% from 2008 to 2012, with 88,042 new cases reported in 2016. This is similar to what was reported by the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control, which reported almost 33,000 confirmed syphilis cases (roughly 8.5 cases per 100,000 population) in the European Union in 2022, reflecting a 34% increase from 2021.

Syphilis is endemic in the developing world and is especially common among those who are poor and have limited access to health care, as over 60% of all new diagnoses come from low and middle-income countries.[17] Prenatal screening for HIV is much more prevalent than for syphilis, primarily due to increased interest and awareness of HIV from local governments and donors, despite the existence of dual HIV/syphilis rapid diagnostic tests. This represents a significant missed public health opportunity to increase testing for syphilis by 100% to 200% in high-risk countries. This is compounded by the fact that most patients with early disease are asymptomatic and reside in communities with limited healthcare resources, so their disease frequently goes unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated.[18]

The incidence of the disease in women doubled from 2013 to 2017 and increased another 147% between 2016 and 2020.[19] This is attributed to a marked increase in parenteral drug abuse, while congenital syphilis cases multiplied 4-fold during approximately the same period.[20][21] Among sex workers, the worldwide incidence of active syphilis in 2019 was 10.8%.

It is estimated that there are 1.5 million congenital syphilis births worldwide annually, mostly in low-income countries, although rates in Western nations are also increasing at alarming rates.[22][23][24][25][26] The CDC reported that the national incidence of congenital syphilis in the US nearly quadrupled between 2015 and 2019 and increased 10-fold over the last 10 years.[27] The 2021 rate was about 78 cases/100,000 live births, which is more than 30% greater than in 2020, and this trend continued through 2023 with an additional 32% increase in just 1 year.[27]

Women aged 24 years and younger have had the greatest increase.[27] Congenital syphilis in the US was 8 and 3.9 times higher among infants born to Black and Hispanic mothers, respectively, compared to White mothers, with almost half of all reported cases coming from California and Texas.[28]

At the same time, federal funding for STD prevention has decreased by 40% over the past 20 years.[29] Even more disturbing was the finding that adequate maternal treatment of syphilis was not performed in over 30% of cases despite an early, timely diagnosis, which represents another significant missed public health improvement opportunity.[20] Impediments to adequate syphilis testing and treatment include lack of prenatal care programs, insufficient syphilis testing, lack of point-of-care tests, missed prenatal visits due to lack of resources, cultural issues, poverty, homelessness, social and cultural stigma, discrimination, lack of health insurance, and substance abuse, particularly methamphetamines and heroin.[28][30][31]

The legacy of the infamous 1932 Tuskegee syphilis experiment is also a factor, where 399 mostly poor Black sharecroppers were deliberately denied treatment for their latent syphilis, even after 1947 when penicillin became the standard therapy, so that researchers could follow the course of the disease.[32][33] This notorious study still causes lingering distrust and deep concern in the Black community regarding healthcare in general and particularly regarding participation in prospective clinical trials.[30][32][33]

A similar but lesser-known study was done in Guatemala from 1946 to 1948 and conducted by the US Public Health Service to determine if penicillin could prevent syphilis. About 700 Guatemalan citizens were deliberately infected with syphilis, and some never received treatment for the disease.[34][35][36]

Promiscuity and sexual behavior play an important role in the transmission of syphilis, as the disease is more common among people with multiple partners, bisexuals, and men who have sex with men (MSM).[37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44]

Men aged 20 to 29 generally have the highest rates of primary and secondary syphilis based on age, with the incidence among MSM in the US (229 cases/100,000) being astronomically higher at 214 times the rate for heterosexual men.[45] The CDC has reported that more than 80% of syphilis cases in the US (primary and secondary) occur in the MSM population, of whom 47% also have HIV.[10] It is estimated that 7.5% of all homosexual males worldwide have the disease compared to about 0.5% of all men in the general population.[46] The probability of syphilis transmission from a single anal sexual act with a single partner in the MSM population was 1.4% and 1% with oral sex. This becomes compounded as the number of sexual encounters and partners increases.[47][48]

Syphilis is an important synergistic infection for HIV acquisition and has been closely linked with HIV infections.[10][44][49][50][51][52] Patients with syphilis are more likely to become HIV positive even if they initially test negative for the virus because of similar behavioral high-risk factors for the 2 diseases.

The steady increase in the incidence of syphilis cases in the US and globally since 2000 makes it a resurging epidemic that requires additional attention and resources for earlier diagnosis and treatment.[53][54] Factors contributing to this resurgence include the following: [40][47][48][52][53][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]

- Improved treatment of HIV, making it seem "safe" to increase sexual contacts and partners without protection (risk compensation)

- The increased use of the internet for dating

- Increasing rates of drug abuse (particularly methamphetamines) are associated with a higher incidence of syphilis infections.

- The improved social acceptability of homosexual behavior (especially MSM)

- The increasing worldwide population with higher numbers of younger individuals who tend to be more sexually active

- Ongoing poverty and homelessness

- The general perception is that syphilis is an "old" disease no longer relevant in modern healthcare, even by some healthcare professionals.

- Lack of familiarity with the disease by modern healthcare practitioners who may have limited experience with syphilis, especially its tertiary manifestations

Pathophysiology

The classic primary syphilis clinical presentation is a solitary nontender genital chancre in response to invasion by the T pallidum. However, patients can have multiple non-genital chancres, such as on the digits, nipples, tonsils, and oral mucosa. These lesions can occur at any site of direct contact with the infected lesion and are accompanied by tender or nontender lymphadenopathy. Some lesions may be in not easily visualized areas, such as in the vagina.

The incubation period before the primary chancre manifestations is about 10 to 90 days, with a median of 21 to 25 days.[19][62][63] Even without treatment, these primary lesions will go away without scarring. If untreated, primary syphilis can progress to secondary syphilis, with many varied clinical and histopathological findings.

The clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis result from hematogenous dissemination of the infection and are protean: condyloma lata (papulosquamous eruption), lesions on the hands and feet, macular rash, diffuse lymphadenopathy, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, pharyngitis, hepatosplenomegaly, alopecia, and malaise.[62][64][65][66][67][68][69]

Both primary and secondary lesions resolve without treatment, and the patient enters either an early or latent phase in which no clinical manifestations are present. The infection can only be detected at this stage with serological testing. Some patients in this stage will progress to the tertiary stage, characterized by cardiovascular syphilis, late neurosyphilis (tabes dorsalis, syphilitic paresis), and late benign syphilis.[17][70][71]

Histopathology

T pallidum is a slowly metabolizing spirochetal bacterium, requiring an average of 30 hours to multiply, and until recently, could not be cultured on artificial media.[72][73][74][75] Its outer membrane lacks lipopolysaccharides and has few surface-exposed unique proteins, making it difficult for the immune system to fight the infection.[76] Because of this characteristic, T pallidum is labeled as a stealth pathogen.[62][76][77][78]

Treponema are thin, tiny Gram-negative organisms that are invisible on routine light microscopy. However, they are identifiable by their distinct spiral movements on darkfield microscopy with an overall sensitivity of 80%.[79] Traditional histopathological silver-impregnation techniques, such as the Warthin–Starry, Dieterle, Steiners, and Levaditi stains, have also been used to visualize Treponema microscopically, but false positives and false negatives are frequent.[19]

Many histopathological features are characteristic of syphilis: interstitial inflammation, inflammatory infiltrates, endothelial swelling, irregular acanthosis, elongated rete ridges, endarteritis (which may be obstructive or obliterative), and a vacuolar pattern with lymphocytic infiltration. Treponemal binding to endothelial cells causes endarteritis, mediated by the bacterial surface fibronectin from the host.

The infiltrate in syphilis is a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to T pallidum. The infiltrate typically consists of plasma cells, lymphocytes, and histiocytes.[62] It is often perivascular and typically demonstrates swelling of the endothelium that can eventually lead to ischemia and even complete arterial occlusion.[62] In some tertiary syphilis patients, sensitized T-lymphocytes and macrophages can form gumma as a reaction. Despite these and other immunological reactions, the net result is usually incomplete and insufficient to eliminate T pallidum from the system.

Silver-staining can detect spirochetes anywhere from 30% to 70% of cases but comes with a high rate of false-negative interpretations. Immunohistochemistry has a sensitivity of about 70% for accurately identifying the infection.[80] If the diagnosis remains uncertain, 16S ribosomal deoxyribonucleic acid (rDNA) sequencing for T pallidum on a tissue sample can be helpful.[81][82]

History and Physical

Syphilis is classified as primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary/late.

Primary Syphilis

This stage is also known as the chancre phase—a chancre is defined as a firm, round, painless ulcer at the site of entry of an infecting organism. Chancres appear 10 to 90 days (median of 21 to 25 days) after exposure to the infecting organism.[19][62] A chancre starts as a papule, usually solitary, at the site of inoculation with the T pallidum spirochete, which is typically on the genitalia. In women, the chancre may appear on the cervix, and since it is painless, the patient is likely to be completely unaware of it.

The papule quickly progresses to a painless, indurated ulcer (chancre) with a raised, thickened border roughly 1 to 2 cm in diameter and a clean, nonexudative base (see Image. Primary Syphilis Chancre).[19] HIV-infected patients typically develop multiple chancres. These chancres resolve without treatment in 3 to 6 weeks but may leave scarring and fibrosis. Mild to moderate regional lymphadenopathy is commonly found in this stage (up to 80% of patients) and consists of rubbery, painless lymph nodes, which may be bilateral.[19][62]

While the chancre represents the initial local reaction to the infection, the bacteria quickly become widely disseminated in the body, including the cerebrospinal fluid, even without any additional immediate symptoms. Up to 70% of early syphilis patients will demonstrate cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) changes consistent with neurosyphilis, and 30% will have direct evidence of T pallidum.[83] Despite this occurrence, very few will develop clinical neurosyphilis.[83]

Secondary Syphilis

This stage develops in approximately one-quarter of all patients infected with T pallidum who go untreated. Symptoms typically appear 2 to 8 weeks after the disappearance of the primary chancre and have multiple systemic manifestations that can involve any system or body part. The T pallidum multiply and spread rapidly, causing fevers, myalgias, headaches, anorexia, sore throat, weight loss, joint pain, malaise, and particularly, the cutaneous manifestations characteristic of secondary syphilis. Enlarged lymph nodes are common in this stage and are usually described as firm, rubbery, and with only minimal tenderness.

A diffuse and extensive maculopapular rash that includes the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, as well as oral lesions in the mouth, are the characteristic cutaneous manifestations of secondary syphilis.[84][85] Involvement of the palms and soles is an important and singular distinguishing feature, although skin lesions in secondary syphilis are highly variable and widespread (see Images. Syphilis, Hand and Keratotic Lesions on the Palms).[17][19][86]

Individual skin lesions are usually small (<6 mm) but may reach 2 cm in size.[19][84] The lesions are usually diffuse, symmetrical, macular, scaly, reddish-brown (copper or ham colored), and not typically pruritic. They may sometimes appear annular or scaling and may include patchy or "moth-eaten" alopecia, mucus patches, a papulosquamous rash, or condyloma lata. While the skin lesions may be pustular, a vesicular rash is not usually present. All such lesions are highly contagious. Up to 20% of patients are unaware of the skin lesions.[84]

The lesions of secondary syphilis generally resolve within a few weeks, even without treatment, but will relapse in 25% of untreated patients, usually within 12 months.[87] After that, without treatment, the disease enters the latent stage, and about 33% of patients will eventually develop tertiary syphilis.[62]

Condyloma lata are hypertrophic wart-like plaques with a flat top, clearly defined pink, fleshy borders, and an erythematous center.[84][88][89] Their appearance may resemble other pathologies, such as Buschke-Lowenstein tumors or condyloma acuminata.[90] They can be painful and may appear in up to 50% of all patients with secondary syphilis, usually in intertriginous areas, particularly around the genitals or rectum and perianal regions.[84][88][89][91][92][93] The lesions are highly infectious and contagious. A definitive diagnosis is made by positive serological testing, dark-field microscopy, or biopsy, where staining with anti-treponemal antibodies is confirmatory.[88][89]

"Lues maligna," or malignant syphilis, is a rare but particularly aggressive form of secondary syphilis, usually found in HIV-positive patients.[94][95][96] The skin manifestations are more significant, persistent, and severe than typical secondary syphilis and are described as ulcerative, oval, and necrotic, with a central, tightly adherent thick crust usually found on the face, limbs, and trunk.[19][94][95][97] Lues maligna is often associated with systemic symptoms and higher T Pallidum bacterial counts than other manifestations of secondary syphilis.[19] When treated, patients with lues malignant are also more likely to develop a severe Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.[19] While usually associated with patients who are immunocompromised or have HIV, it has also now been described in some immunocompetent individuals.[98][99][100][101][102][103] Other risk factors for lues maligna include diabetes, a history of drug abuse, psoriasis, alcoholism, syphilitic hepatitis (characterized by high serum alkaline phosphatase levels), musculoskeletal disorders, transient nephropathy with proteinuria, and even acute renal failure.[19][64][101][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112]

Tertiary (or Late) Syphilis

Tertiary syphilis is a late symptomatic disease that can manifest months, years, or even decades after the initial infection as cardiovascular syphilis (aortic aneurysm, aortic valvulopathy), neurosyphilis (meningitis, hemiplegia, stroke, aphasia, seizures, spinal neuroarthropathy, tabes dorsalis, syphilitic paresis), or gummatous syphilis (infiltration of any organ and its subsequent destruction).[19] Between 25% and 40% of all patients with untreated syphilis may eventually develop tertiary disease, although this may take 20 or 30 years to become clinically apparent. Prior clinical history, evidence, or symptoms of primary or secondary syphilis may or may not be present.

Neurosyphilis

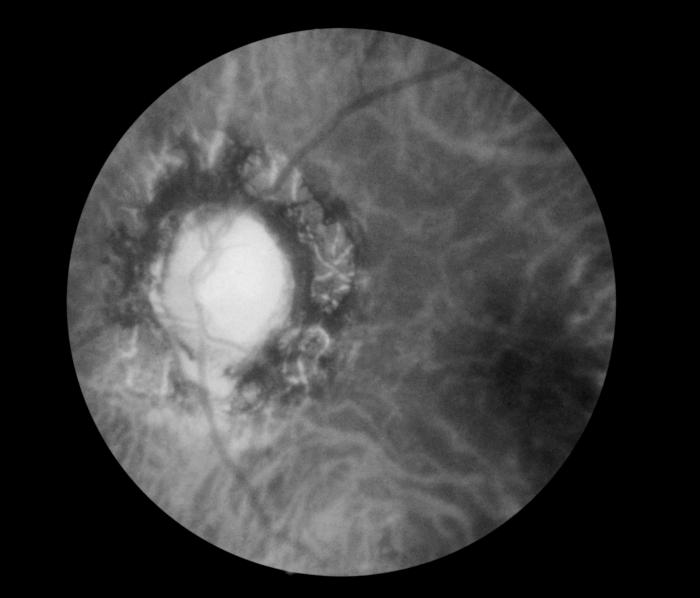

Neurosyphilis can be categorized into early, intermediate, and late stages. About 30% of patients with an untreated T pallidum infection will demonstrate CSF abnormalities consistent with syphilis, but most will not develop neurological symptoms or clinical neurosyphilis.[83] In addition, patients may develop ocular or otic symptoms at any time of infection; these manifestations are also considered neurosyphilis presentations (see Image. Fundoscopic Image of Late Neuroocular Syphilis). Please see StatPearls' companion reference, "Neurosyphilis," for further information.[71]

Neurosyphilis Classification Summary:

Early/Intermediate Neurosyphilis

- Asymptomatic Neurosyphilis

- The most common form of neurosyphilis

- Defined as suggestive CSF abnormalities in a patient with serological evidence of syphilis but no neurological symptoms

- Meningeal Neurosyphilis (presents at <1 year after primary infection)

- Results from diffuse inflammation of the meninges

- Typical meningeal symptoms include headache, nausea, vomiting, neck stiffness, photophobia, cranial nerve deficits, and seizures.

- Imaging may show enhancement of the meninges or select cranial nerves.

- Meningovascular Neurosyphilis (presents at 5 to 12 years after primary infection)

- Defined as inflammation of the meninges, as well as endarteritis causing thrombosis and infarction of cerebral tissue

- Early symptoms are nonspecific, including headache, nausea, vomiting, and vertigo.

- Symptoms depend on the site of thrombosis and the corresponding cerebral functions.

- Spinal cord vessels may also be affected, resulting in meningomyelitis and spastic weakness (particularly in the lower extremities), sensory loss, and muscular atrophy.

Late Neurosyphilis (Parenchymal) (presents >10 years, sometimes decades after primary infection)

- Syphilitic Paresis (general paralysis of the insane, paralytic dementia, general paresis)

- Caused by chronic meningoencephalitis resulting in cerebral atrophy

- Symptoms can occur insidiously or suddenly and can be further divided into early and late.

- Early symptoms include mood disturbances such as irritability, personality changes, alterations in sleep habits, and forgetfulness.

- Late symptoms include labile mood, memory and judgment impairment, confusion, depression, agitation, psychosis, delusions, and seizures.

- Neurologically, the clinician may see ophthalmic abnormalities, dysarthria, and tremors.

- Tabes Dorsalis

- Results from the degeneration of the posterior (dorsal) column and roots of the spinal cord

- Classically, patients have an unsteady gait, balance issues, lancinating or stabbing pains, bladder dysfunction, paresthesias, loss of proprioception, visceral crises, and visual changes.

- Romberg test is positive.

- Additional neurologic deficits include Argyll Robertson pupils, ocular palsies, diminished reflexes, vibratory and proprioceptive impairment, and Charcot joints.

Late neurosyphilis describes neurological manifestations in tertiary syphilis and would include tables dorsalis, Charcot spine (spinal neuroarthropathy), and syphilitic paresis (general paresis, general paralysis of the insane, dementia paralytica). It accounts for 5% to 10% of all tertiary syphilis cases. Please see StatPearls' companion references, "Neurosyphilis" and "Tabes Dorsalis," for further information.[71]

Cardiovascular Syphilis

Cardiovascular syphilis is the most frequently encountered clinical manifestation of tertiary syphilis, accounting for 80% to 85% of such cases or about 10% of all untreated syphilis cases.[16] Symptoms of cardiovascular syphilis do not develop until at least 10 years after the initial primary infection, usually between 15 and 30 years. Symptoms tend to develop very slowly and insidiously.

The most common clinical finding is an ascending aortic aneurysm due to vasculitis and inflammation of the arteries that supply the walls of the aorta in almost 50% of affected individuals.[16][113][114][115] The aorta develops white, shiny foci of intimal thickening, sometimes described as "tree bark" in appearance. Chest x-rays may show unusual calcifications involving the ascending aortic arch, which is not typically seen with atherosclerotic disease. Fortunately, these aortic lesions rarely progress to dissecting aneurysms, but they can cause left heart failure and aortic valve insufficiency.[115] Over time, fibrous thickening and scarring of the adventitia or aortic intima develop, resulting in a wrinkled appearance. Other manifestations include aortitis and mucinous myocarditis.[114][116]

The coronary arteries may also be affected, resulting in luminal narrowing, leading to possible ischemia as well as an increased risk of thrombosis and myocardial infarction.[117][118][119] Syphilis should be considered whenever aortic valve regurgitation or insufficiency is encountered in younger adults.[117][118][120] If cardiovascular syphilis is confirmed, a CSF examination should be performed. Besides antibiotics, cardiovascular syphilis may require cardiothoracic surgery with aortic valve replacement or repair of aortic aneurysms.[121]

Gummatous Syphilis

Gummatous syphilis is a rare form of tertiary disease manifested by gummas (granulomatous nodules with a somewhat rubbery texture and necrotic centers) that typically affect the skin and are most often found internally in the liver as well as the testes, brain, heart, and bone but can also develop in any organ. The gummas rarely demonstrate any active T Pallidum but can ulcerate and slowly become fibrotic over time. MRI diffusion-weighted imaging will clearly demonstrate syphilitic cerebral gumma, including nodular enhancement, somewhat restricted diffusion, general peripheral edema, and a possible dural tail.[122][123][124]

When they appear on the skin, the gummas may appear as superficial flat ulcers or, less often, as granulomatous lesions of any size and with a variable shape (see Image. Syphilis Gummas Lesion).[125][126] As the lesions may appear similar to granulomas, they can be easily mistaken for other diseases such as sarcoid and tuberculosis.[125] Multinucleated giant cells may be found, as well as caseating necrosis.[125] Gummatous syphilis tends to be associated with HIV infections.

Congenital Syphilis

Congenital syphilis results from transplacental transmission or contact with infectious lesions during birth and can be acquired at any stage, often causing stillbirth or neonatal congenital infections. In the US, congenital syphilis is higher in mothers with drug abuse and those without prenatal care during their pregnancy, and it is disproportionately higher in the Black population.[127]

The WHO estimates that worldwide, 7 out of every 1000 pregnant women are infected with syphilis, and over 1.5 million infants are born with congenital syphilis.[26] Without treatment, up to 40% of women with syphilis will have stillborn births, and many more will have premature labor or low-birth-weight babies.[128][129][130] Unfortunately, from 2012 to 2022, the incidence of congenital syphilis in the US increased more than 10-fold, representing a major public health failure.[19][27]

Routine screening is recommended at the first prenatal visit, early during the third trimester (around 28 weeks), and at the time of delivery, especially in high-risk mothers.[130][131] The fetus often becomes infected as the bacteria easily cross the placental barrier. Most neonates (70%) born with congenital syphilis are asymptomatic at birth, and a growing number are not diagnosed until 1 month or longer after delivery.[132][133]

In a normal pregnancy, the weight of the placenta will increase along with gestational age.[134] If infected with syphilis, the placentas tend to enlarge beyond the expected range due to localized inflammation.[135][136][137] More than three-quarters (76%) of infants born with a placenta larger than the 90th percentile for their birth weight were found to have congenital syphilis, and it is therefore suggested that such neonates and their mothers receive serological syphilis testing.[138][130] Prenatal ultrasonography of an infected fetus may demonstrate various abnormalities, such as hepatomegaly, placental enlargement, and hydrops fetalis, starting at 18 weeks gestation.[139][140]

Most neonates with congenital syphilis are asymptomatic at birth but develop symptoms within the first 3 months.[62][130] The most common findings in neonates with congenital syphilis are a generalized bullous rash, anemia, jaundice, and hepatosplenomegaly.[62][130] Other manifestations are nasal cartilage destruction (saddle nose), frontal bossing (Olympian brow), bowing of the tibia (saber shins), measles-like or bullous rash, rhinitis (sniffles), sterile joint effusion (Clutton joints), peg-shaped upper central incisors (Hutchinson teeth), fetal hydrops, hepatosplenomegaly, jaundice, anemia, pseudoparalysis of an extremity, and a desquamating skin rash that develops a few months after birth.[130]

All neonates born to mothers with positive serology should be evaluated with a VDRL or RPR test.[133][130][141] However, since maternal IgG antibodies cross the placenta, interpreting positive treponemal serology testing in neonates can be problematic.[130] In such cases, the diagnosis is based on maternal testing, other clinical evidence of congenital syphilis in the neonate, as well as a comparison of maternal and neonatal nontreponemal serological titers.[62][130]

As adults, about 30% of affected patients who are untreated can develop tabes dorsalis, syphilitic paresis, nerve-related deafness, and ocular syphilis, resulting in possible visual disturbances or even blindness.[130][139][142] Adverse outcomes from maternal syphilis can be effectively prevented with a single IM injection of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G administered before week 28 of gestation.[130][143] This is 98% effective in eliminating congenital syphilis in the neonate but must be given 30 days or more prior to delivery.[130] Some experts recommend a second dose of benzathine penicillin 1 week later.[130][144][145][146][147]

Congenital syphilis can be a diagnostic challenge as maternal antibodies are transferable to the fetus. Such antibodies can persist for 15 months.[130] Darkfield microscopy or PCR testing of any suspicious lesions on the neonate should be performed. Further workup for suspected cases of congenital syphilis includes x-rays of the long bones, a complete blood count (CBC), and an analysis of CSF fluid for white blood cell (WBC) count, protein, and a VDRL titer.[130]

See StatPearls' companion reference, "Congenital and Maternal Syphilis," for more detailed information.[130]

Evaluation

Diagnostic strategies for syphilis consist of dark-field microscopy and serum, tissue, or CSF serological testing.

Microscopic darkfield examination, discovered in 1906, allows for the direct visual examination of spirochetes from syphilitic mucosal lesions and exudates. Lesions must be moist, and the microscopy must be done right after the specimen is obtained. It is particularly useful in very early syphilis and in immunocompromised individuals where serological reactivity to T pallidum may be delayed or has not yet developed.[148][149]

Darkfield microscopy offers an immediate diagnosis if positive, but it can miss up to 20% of syphilis cases, especially if the patient has applied topical antibiotics or if the microscopist is inexperienced. The finding of T pallidum on darkfield microscopic examination is considered definitive proof of syphilis, but failing to find the organism does not definitively rule out the diagnosis. The sensitivity of darkfield microscopy tends to decrease over time, and it is not useful for oral lesions as these can demonstrate nonpathological Treponema bacteria, resulting in false positives.[148]

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays can be performed on serum or tissue samples.[150] High sensitivity (78% to 95%) and specificity (95% to 100%) have been reported, and PCR testing is recommended in the European guidelines.[63][150][151] PCR tests can be done on serum, CSF, or tissue samples, but CSF results are only moderately sensitive (about the same as CSF VDRL).[150] PCR testing for T pallidum directly from fresh mucosal specimens is not sufficiently sensitive for clinical diagnostic use when tested in high-risk populations and is not currently recommended.[152]

Darkfield microscopy and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays for T pallidum are not generally available in the US, and silver-staining techniques are considered unreliable.[19] Nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs) can be clinically helpful but have not been approved by the FDA for use in the US.[144][139] Therefore, serological testing is the preferred primary diagnostic modality for syphilis.[19][144]

Serological testing for syphilis is classified as either nontreponemal or treponemal.

Nontreponemal tests for syphilis (venereal disease research laboratory [VDRL] and rapid plasma reagin [RPR]) are screening examinations that detect IgG and IgM antibodies to the patient's cardiolipin that have become integrated with the T pallidum bacteria in the blood or CSF and are therefore not absolutely specific for syphilis.[11][19] The Unheated Serum Reagin (USR) and Toluidine Red Unheated Serum Test (TRUST) are examples of other nontreponemal serological tests.

The VDRL and RPR tests are only positive after the development of the primary chancre.[11][153] The VDRL assay becomes detectable after the first few weeks following the initial inoculation of T pallidum.[154] It reaches peak levels within the first year and then slowly declines thereafter.[154][155] By the tertiary (late) stages of syphilis, VDRL titers are usually low or undetectable.[154]

These tests are relatively inexpensive and simple but somewhat time-consuming to perform as they require a trained laboratory technician. They constitute the usual initial standard screening serological tests for syphilis but are not point-of-care examinations. Test results can be quantified by performing serial dilutions and used for tracking the progress of the infection, as a 4-fold change in titer would be considered clinically significant.[11][154][156]

VDRL titers are typically lower than RPR as the 2 tests are not equivalent, and assay levels cannot be used interchangeably.[19][157] The VDRL assay is preferred for screening the CSF, where it is more sensitive, while the RPR is generally preferred for disease tracking as it declines more rapidly after therapy than the VDRL.[158] Unfortunately, false-positive tests are relatively common at 1% to 2%, and nontreponemal tests are not specific for syphilis, so an additional confirmatory treponemal serum antibody test is required for a definitive diagnosis.[11][12][154] Please see StatPearls' companion reference, "Rapid Plasma Reagin," for further information.

Treponemal antibody tests (fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay [FTA-ABS], T pallidum particle agglutination assay [TPPA], T pallidum hemagglutination assay [TPHA], chemiluminescent immunoassay [CIA], enzyme immunoassay [EIA], and rapid chromatographic immunoassays) that detect specific serum antibodies to T pallidum are considered necessary and required for a confirmed diagnosis of syphilis when the VDRL or RPR tests are initially positive.[12] Of these, the most sensitive and preferred confirmatory treponemal antibody tests would be the FTA-ABS or the TPPA for all syphilis stages, where available, although the TPPA is considered more specific.[12]

While they turn positive early and are specific, treponemal antibody tests do not match or follow the stage, progression, or severity of the bacterial infection.[12] They are also positive for life and, therefore, cannot be used for disease tracking, but versions are suitable for initial point-of-care and home testing.[12]

The use of a T pallidum transcription-mediated amplification assay of urine and mucosal specimens has experimentally been found to help identify some patients suspected of having syphilis with negative serology, although a negative result does not completely rule out a syphilis diagnosis.[159][160][161]

A new treponemal IgA-enzyme immunoassay has shown good sensitivity and specificity in detecting syphilis in early testing, but further evaluation and studies are needed before it can be made available for clinical use.[162]

Reverse sequence screening is an increasingly used algorithm in US laboratories where treponemal antibody tests are used for the initial screening to identify those patients with treated, untreated, or incompletely treated syphilis.[163][164][165] This is performed because of the availability of rapid, inexpensive, automated laboratory treponemal antibody testing instruments.[164][165]

If such a treponemal antibody test is positive, a nontreponemal assay (VDRL, RPR) is necessary to determine if the disease is active.[164] Because of a lack of validation of the reverse algorithm, higher rates of false-positive results can be seen, leading to difficulty interpreting these results and the need for additional confirmatory testing.[166][165] Reverse sequence screenings are most appropriate in low-risk populations in communities and countries where the prevalence of syphilis is already very low.[17]

Suspected neurosyphilis (syphilis patients with neurologic symptoms) will require an examination of the cerebrospinal fluid from a lumbar puncture for a definitive diagnosis.[167] This diagnosis is important because the treatment regimen for individuals with neurosyphilis is different from those without neurosyphilis. If this is not possible or there is a significant risk of patient noncompliance, it may be advisable to treat the patient for neurosyphilis rather than risk losing the patient and letting them go untreated.

Guidelines for Performing a Cerebrospinal Fluid Analysis in Syphilis Patients [71][168][155][167][169][170][171][172][173][174]

CSF analysis should be considered in the following situations:

- Failure of initial treatment of syphilis

- HIV-positivity (recommended by European Guidelines)

- Newly diagnosed psychiatric illness in areas of high syphilis prevalence (especially if associated with cognitive decline or dementia)

- Newly diagnosed syphilis of unknown duration

- Ocular syphilis (controversial)

- Serum RPR assay level of 1:32 or higher

- Tertiary syphilis (even without neurological signs)

- Untreated or latent syphilis that is known to be present for at least 1 year

VDRL testing of the CSF is not sensitive but is very specific for neurosyphilis, while treponemal antibody testing is highly sensitive but not specific (risk of false positive), as treponemal antibodies often remain elevated even once treated and can cross the blood-brain barrier.[175][176][177] Therefore, both tests are frequently needed to confirm the diagnosis. VDRL is preferred for CSF evaluations as it is more sensitive than the RPR, but it still only reacts positively in the CSF in 67% to 72% of neurosyphilis patients.[158][178] A positive CSF VDRL titer is very specific and diagnostic but is not very sensitive, so a negative CSF VDRL test does not rule out the diagnosis.[179] Up to 25% of CSF VDRL tests are negative in tabes dorsalis.[71] However, a negative CSF VDRL with a negative treponemal CSF test makes neurosyphilis highly unlikely.[180][181][182]

If suspicion is high for neurosyphilis, treponemal antibody testing of the CSF should be considered, even if the CSF-VDRL is negative.[12][183] The CSF FTA-ABS test has long been used off-label to exclude neurosyphilis as it has a high sensitivity of 90% to 100% but is not FDA-approved.[179][184][185] If the test is negative, it is strong evidence against the presence of neurosyphilis.[179] CSF WBC count and protein should also be taken into account.

The 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for T pallidum can also be performed on biopsy specimens where the diagnosis cannot otherwise be confirmed.[81][82]

Unique CSF biomarkers are being studied and appear promising in helping to diagnose neurosyphilis in otherwise borderline or equivocal cases, where available. These include beta-2 microglobulin and CSCL13 (at a suggested threshold of 10 pg/mL or more) and anti-treponemal IgA assays.[177][184][162][186][187]

Please see StatPearls' companion reference, "Neurosyphilis," for further details on the diagnostic evaluation of neurosyphilis.[71]

All patients with syphilis should be tested for other STDs, particularly HIV. Conversely, all HIV-positive patients should be serologically tested for syphilis. Benzathine penicillin G should be administered if the serology tests are positive, and follow-up testing should be scheduled.

Imaging studies depend on the organ involved. A chest x-ray may be the first clue to the presence of an aortic aneurysm. A CT scan can confirm this. An echocardiogram is needed to rule out aortic regurgitation, while long-bone x-rays may be useful in neonates. Imaging in neurosyphilis may show brain infarcts associated with meningovascular syphilis, cerebral atrophy along with high-intensity T2-weighted imaging involving the hippocampus, frontotemporal lobes, and periventricular regions in syphilitic paresis, and abnormalities involving the dorsal spinal columns in tabes dorsalis.[169][188][189][190]

Neuroimaging is not typically necessary in the evaluation of possible neurosyphilis as the findings tend to be nonspecific. Imaging is recommended only if some other pathology is suspected or there is evidence of increased intracranial pressure.[169]

Rapid point-of-care tests for syphilis are now available without the need for high-tech equipment.[191][192] These tests are simple to perform, easy to interpret, and can be conveniently stored at room temperature.[191][192] Results are available in 15 to 30 minutes and only require a single drop of blood from a finger stick, so immediate treatment can be provided for those who test positive.[62] The WHO recommended standards require a minimum of 85% sensitivity and 95% specificity for such tests.[193] The reported sensitivities of commercially available tests are 76% to 86%, with specificities of 96% to 99%.[194][195] A few rapid point-of-care tests have combined both treponemal and nontreponemal testing (preferred), but most are antibody-based and require confirmation with a nontreponemal assay.[196][197][198][199] Some of these also include HIV testing.

Rapid point-of-care testing is not a replacement for traditional reference laboratory serological examinations. Still, it can be beneficial where syphilis prevalence is high, follow-up is uncertain, and healthcare resources are limited, especially for high-risk populations, such as pregnant women, MSM, and HIV-positive individuals.[141][200][201] In the US, such tests may be useful for screening high-risk populations in poorly served medical communities and emergency facilities, particularly when adequate follow-up is problematic.[201][202] Global implementation of such rapid point-of-care testing, especially in regions of high syphilis prevalence and limited healthcare resources, can significantly improve outcomes and save lives.[202][203][204][205][206][207] See StatPearls' companion reference article on "Point-of-Care Testing."[208] Syphilis is a reportable disease but is still thought to be significantly underreported globally.

Summary

Syphilis is known as "the great imitator" due to its great variety of different presentations.[65] As the noted physician Sir William Osler once said, "He who knows syphilis knows medicine."[209]

A definitive diagnosis of syphilis generally requires at least 1 positive nontreponemal assay (VDRL, RPR) and a positive treponemal test (FTA-ABS, TPPA, TPHA, TPHA, CIA, or EIA).[19] Only the nontreponemal tests can be used for disease tracking as the treponemal antibody assays are usually positive for life and do not correlate well with disease status, progression, or severity.[19] CSF testing may be needed in some cases, such as those with neurological symptoms or other evidence suggesting possible neurosyphilis.[19][71]

A positive VDRL test in the CSF is highly suggestive of neurosyphilis, but a negative test does not definitively rule it out.[19][71] A combination of history, clinical findings, serology with both nontreponemal and treponemal confirmatory testing, and a CSF examination, when appropriate, is necessary to establish and confirm the diagnosis.[19][71]

Treatment / Management

Penicillin is the preferred bacteriocidal antibiotic for all stages of syphilis. It is most effective when bacteria are quickly reproducing. Treponema spp divide only once every 30 hours, so longer-acting forms of the antibiotic are typically preferred (procaine and benzathine penicillin), except for neurosyphilis where aqueous formulations are recommended as they can attain higher CSF concentrations.[210] (Note: procaine penicillin G is no longer manufactured in the US and may be unavailable.)

Penicillin works by permanently inactivating an enzyme required for bacterial cell wall growth and repair.[211][212][213][214][215][216][217][218] Without this critical enzyme, Treponema cannot grow or reproduce and experience explosive cell lysis from osmotic pressure, as large volumes of fluid are rapidly forced into the bacteria.[211][212][213][214][215][216][217][218]

Treatment of syphilis depends on the disease stage, as recommended by the CDC as follows: [166][167]

- Primary, secondary, and early latent syphilis are treated with a single dose of intramuscular (IM) benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units.

- Tertiary, late latent syphilis, and HIV-infected patients with the disease should be treated with 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G IM weekly for 3 weeks.

- Neurosyphilis, including ocular disease and otosyphilis, should be treated with IV aqueous crystalline penicillin G 18 million to 24 million units (as a continuous IV infusion or 3 to 4 million units IV every 4 hours) daily for 10 to 14 days.

- An alternative regimen for neurosyphilis would be procaine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM once daily, if available, AND Probenecid 500 mg orally 4 times per day for 10 to 14 days.

- An additional 1 to 3 weekly doses of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G is considered optional to extend the duration of treatment in neurosyphilis. Pharmacodynamically, a single additional dose should be sufficient to do this.[169][219]

- Doxycycline is not recommended for the treatment of neurosyphilis by the CDC or the European guidelines, although it is approved for this purpose in the UK.

- See StatPearls' companion reference, "Benzathine Penicillin," for more information.[220]

- The CDC now recommends that most patients treated for neurosyphilis (immunocompetent individuals and adequately treated HIV-positive patients) can now be followed by serum nontreponemal testing without the need for repeat CSF examinations.[167][221][222]

Alternative therapies include doxycycline 100 mg orally (PO) twice daily for 14 days, ceftriaxone 1 to 2 gm IM or intravenously (IV) daily for 10 to 14 days, or tetracycline 100 mg PO 4 times daily for 14 days.

Azithromycin is no longer recommended due to reports of resistance, except in cases where resistance is low and alternative antibiotics cannot be used.[223][224][225][226][227][228](B2)

Patients must be followed posttreatment at 6, 12, and 24 months after therapy with a clinical evaluation and serial nontreponemal (VDRL and RPR) testing. In addition, re-examinations at 3 and 9 months are suggested for high-risk individuals. A 4-fold decline in nontreponemal test titers indicates successful treatment, while a 4-fold increase from the initial level suggests reinfection or therapy failure.[229][230] (A1)

Linezolid is a synthetic low-cost, oral, or injectable antibiotic that inhibits bacterial protein synthesis.[230][231][232][233] It is primarily used for gram-positive bacterial pneumonia, skin, and soft-tissue infections and as an alternative to vancomycin.[231][232][233][234] Experimentally, linezolid has shown activity similar to benzathine penicillin G in animal models and newly developed tissue cultures.[72][232] It is not formally approved for the treatment of syphilis.(A1)

Pregnancy and Syphilis

All pregnant patients should be tested for syphilis at their initial prenatal visit or at their first obstetrical visit, whichever comes first. Pregnant patients who test positive for syphilis should have nontreponemal testing to track their titers. Serological testing is recommended during the third trimester, at 28 weeks, after exposure to an infected partner, and at delivery for high-risk patients.[235]

Adverse outcomes from maternal syphilis can be effectively prevented with a single IM injection of 2.4 million units of benzathine penicillin G administered before week 28 of gestation.[130][143][144][145][146][147] This is 98% effective in eliminating congenital syphilis in the neonate, but must be given 30 days or more prior to delivery.[130] A second dose of benzathine penicillin 1 week later is recommended by some experts, especially if there is evidence of fetal involvement.[130][144][145][146][147][236] Fetal monitoring is recommended when starting antimicrobial therapy in pregnant women with syphilis due to a possible Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.[237](A1)

In areas of high syphilis prevalence, pregnant patients found to be positive on rapid point-of-care syphilis tests should be immediately treated with benzathine penicillin G without waiting for confirmational laboratory testing. This strategy helps avoid complications of poor follow-up.[62][130][143][145][238][239](B2)

Mothers should be tested for syphilis after 20 weeks of gestation in any fetal death. All mothers who test positive for syphilis should also be tested for HIV and vice-versa.

Ultrasonography of the fetus for signs of congenital syphilis is recommended when the disease has been diagnosed during the second half of the mother's pregnancy. Sonographic signs of congenital syphilis include ascites, hepatomegaly, hydrops, and a thickened placenta.[240][241] Such prenatal signs suggest a higher risk of treatment failure in the fetus as well as a higher risk of encountering fetal distress, premature labor, or a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction.[240][241]

Treating syphilis during pregnancy is the same as for nonpregnant patients based on their stage of infection. There is no evidence that corticosteroid treatment helps minimize complications when treating syphilis during pregnancy. Pregnant women who miss a scheduled therapy dose by 2 days or more must have their entire treatment repeated.

A 4-fold decrease in nontreponemal titers is optimal but may not be achieved before delivery, even in properly treated patients.[242] This does not necessarily indicate a treatment failure.[242] However, a 4-fold increase in titers present for 2 weeks or more is likely a treatment failure or a reinfection. Repeat titers are not recommended until at least 2 months after treatment.(B2)

There are no known acceptable proven alternatives to penicillin for the treatment of syphilis during pregnancy. Therefore, pregnant women who are penicillin allergic should be skin tested to identify their actual risk and undergo desensitization so they can be treated with penicillin.[243] Many patients labeled with penicillin allergy have only a mild intolerance, so this should be confirmed. Please see Statpearls' companion reference, "Penicillin Allergy," for further information.[244] Doxycycline and tetracyclines, in particular, should be avoided in the latter stages of pregnancy, and insufficient data on ceftriaxone and cephalosporins precludes their use. Azithromycin and erythromycin do not reliably cure the mother and will not adequately treat the fetus.[146] If it is determined that an alternative medication is absolutely required, cefriaxone is suggested.[62]

A Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction is possible in patients with a high titer of primary or secondary syphilis. This self-limited immune-mediated response occurs within 2 to 24 hours of antibiotic treatment and is characterized by high fever, headache, myalgias, and rash.[237] Pregnant women who develop a Jacob-Herxheimer reaction need to be observed closely, as it can lead to obstetric complications such as fetal distress and the induction of early labor. Fetal monitoring is recommended during this period. The risk is estimated at about 40%. Despite this risk, treatment of syphilis should not be delayed. Please see the companion StatPearls' reference review, "Jarisch-Hexheimer reaction," for more information.[237]

Congenital Syphilis

Treatment of congenital syphilis is aqueous crystalline penicillin G at 100,000 units/kg to 150,000 units/kg body weight/day. This is given as 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose IV every 12 hours during the first 7 days after birth, then every 8 hours for 10 days. If available, an alternative regimen is procaine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose IM in a single daily dose for 10 days.[130]

Ten-day treatment protocols are recommended for neonates with proven syphilis or those at moderate to high risk. Lower-risk newborns may be treated with a single IM dose of benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight as an alternative therapy for congenital syphilis if their recommended testing is negative.[130]

Neonates with a positive nontreponemal test (VDRL or RPR) should be retested at least every 3 months until they become nonreactive. If a baby was not treated as his risk was considered low, his nontreponemal test titers should drop by 3 months and become nonreactive after 6 months. If so, no further treatment or evaluation is needed. If the testing still shows positive titers, the infant should be treated as a congenital syphilis neonate and given a 10-day course of IV penicillin as above.[130] If CSF titers remain positive after 18 months, retreatment for neurosyphilis is indicated.[130]

Pediatric Syphilis

Older children who test positive serologically for syphilis should have a CBC with differential and a CSF examination for cell count, protein, and a VDRL titer. Other optional tests would include x-rays of the long bones, chest x-rays, liver function studies, abdominal ultrasound, neurological imaging, auditory brain-stem response, and an ophthalmologic evaluation as clinically indicated.

The standard treatment for pediatric syphilis is aqueous crystalline penicillin G at 200,000 units/kg to 300,000 units/kg body weight/day IV. The medication is administered at 50,000 units/kg of body weight every 4 to 6 hours for 10 days. This is followed by a single dose of benzathine penicillin G at 50,000 units/kg body weight (up to a maximum of 2.4 million units).

If there are no clinical manifestations of syphilis and the evaluation is otherwise normal (ie, negative VDRL of the CSF, normal CBC), consideration can be given to treating the child with 3 weekly doses of IM benzathine penicillin G 50,000 units/kg body weight/dose (up to a maximum of 2.4 million units/IM injection).

Patients with a Penicillin Allergy May Still be Treatable with Penicillin [245][244][246](B3)

Few patients (<9%) who report a penicillin allergy have it specifically confirmed.[247][248] The vast majority of patients who believe they have a penicillin allergy can safely receive penicillin. Many patients mistakenly believe they have a penicillin allergy when they actually had a secondary viral infection, a Jarishck-Herxhemer reaction, or a mild penicillin intolerance.[244] This is significant in a disease like syphilis, where penicillin is most-proven efficacious. Even among those with a well-documented IgE-mediated allergic reaction, about 80% will lose their sensitivity to penicillin after 10 years.[249]

Ceftriaxone is considered a reasonable syphilis therapeutic alternative to penicillin by the CDC, European guidelines, and the WHO due to drug shortages, severe allergic reactions, patient refusal, or other reasons.[150][250][251][252][253] The antibiotic easily crosses the blood-brain barrier as well as the placenta, is safe for the fetus, and is very effective in killing T pallidum at low serum concentrations.[254][255] Even with the reduced drug levels in the amniotic fluid and fetal serum, the concentration of ceftriaxone is still well above the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for T pallidum.[254][255][256](A1)

- Most patients (>90%) with a presumed penicillin allergy are not actually allergic.

- Skin testing to confirm the penicillin allergy should be considered, as penicillin is still the strongly preferred antimicrobial for syphilis, especially neurosyphilis, and in pregnancy.

- Skin testing should NOT be performed in patients with a history of severe allergic reactions to penicillin, such as anaphylaxis, toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, interstitial nephritis, or hemolytic anemia.

- If the skin testing is negative, this is usually followed by an oral penicillin challenge with amoxicillin.

- For those who test positive, desensitization by an allergist can be considered, especially during pregnancy and in patients with neurosyphilis, where alternative medications are not recommended.

- Anecdotally, ceftriaxone has been used successfully.[257]

- An algorithm for penicillin use in pregnant patients with penicillin allergies is available.[257][258][259][260] (B2)

For further details on the treatment of syphilis, see the respective companion Statpearls' references on "Sexually Transmitted Infections," "Neurosyphilis," "Congenital Syphilis," and "Penicillin Allergy."[71][130][244][261]

Preventing Syphilis

Benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM as a single dose should be administered if a person has unprotected sexual relations with an individual known to have syphilis.

Recently, there has been interest in the use of 200 mg of doxycycline optimally administered up to 72 hours after direct sexual contact (doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis or doxy-PEP). This has been shown to significantly reduce the development of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and especially syphilis by roughly two-thirds when used in a high-risk population such as MSM.[169][221][222][262][263] Limited implementation of such a program in San Francisco has shown a syphilis rate reduction of 50% compared to the expected rate in the target population.

Issues limiting the more widespread adoption of this postexposure prophylaxis include a lack of consensus regarding which high-risk groups should receive doxy-PEP, the potential side effects of wider implementation, the lack of any long-term safety data, and the real concern about promoting antibiotic resistance.[263] The CDC is reviewing this issue and is expected to issue guidelines on doxy-PEP shortly.

WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Syphilis [251]

- Benzathine penicillin G administered intramuscularly is the treatment of choice.

- Procaine penicillin is the second choice and is administered intramuscularly for 10 to 14 days.

- If penicillin cannot be used, doxycycline, azithromycin, or ceftriaxone are other options. Azithromycin is not preferred due to increasing resistance.

- Doxycycline is preferred as an alternative oral agent as it is cheap and easy to administer. However, it is not recommended for children or pregnant women.

- Azithromycin does not cross the placenta, so the infant must be treated after delivery if this drug is used.

Differential Diagnosis

Conditions that can present with signs and symptoms similar to syphilis include the following:

- Behcet syndrome

- Chancroid

- Contact or atopic dermatitis

- Dementia

- Erythema multiforme

- Genital herpes

- Granuloma inguinale

- Lymphogranuloma venereum

- Lymphoma

- Mononucleosis

- Pityriasis rosea

- Psychiatric illness

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever

- Uveitis

- Viral exanthema

Prognosis

Understanding the prognosis of syphilis is crucial for guiding treatment decisions and informing patients about potential outcomes. The prognosis of syphilis depends on the stage and extent of organ involvement. If left untreated, the causative organism renders significant morbidity and mortality. Patients usually develop cardiovascular and CNS syphilis, which can be fatal if untreated.

Congenital syphilis is associated with spontaneous abortions, stillbirth, and infant mortality. Without treatment during pregnancy, syphilis is almost always passed on to the fetus.

Complications

Untreated syphilis infection can lead to irreversible neurological and cardiovascular complications. Depending on the stage, neurosyphilis can manifest as meningitis, stroke, cranial nerve palsies during early neurosyphilis or tabes dorsalis, dementia, and general paresis during late neurosyphilis. Cardiovascular syphilis is also a result of tertiary syphilis and can manifest as aortitis, aortic regurgitation, carotid ostial stenosis, or granulomatosis lesions (gummas) in various body organs. Untreated syphilis affects the course of HIV infection with higher virus replication rates and lower CD4 counts. There is also a faster rate of progression to late syphilis.[230]

Primary and secondary syphilis during pregnancy lead to neonatal infections with congenital syphilis and adverse pregnancy outcomes if not identified promptly and treated.

Consultations

It is recommended for the primary physician to consult with an infectious disease specialist regarding confirmation of the disease, treatment, and follow-up. Pediatric infectious disease specialists are best suited to manage congenital syphilis. Rehabilitation practitioners, dermatologists, orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, ophthalmologists, pediatricians, obstetricians, and ENT specialists should also be consulted as appropriate.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given the increasing incidence of syphilis around the world, especially in underserved or poorer populations, self-testing is a technique that has the potential to reach individuals with limited healthcare access and greatly increase early diagnosis, similar to what is currently available for COVID-19.[203][264][265][266] Self-testing is socially acceptable and even preferred by many people and many physicians for initial screening. It is feasible to implement, convenient, cost-effective, maintains patient privacy, provides rapid results, minimizes depleting healthcare facility resources, and avoids unnecessary clinic visits while promoting follow-up appointment compliance for those who test positive.[239][203][264][265]

Home STD testing is essentially the same technology as rapid point-of-care tests. Home testing is associated with higher testing rates for both sexes than clinic testing, with an overall sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 96%.[267] For syphilis, the reported sensitivity is 85%, with a specificity of 91%, although there is an issue with inadequate blood samples being used in some cases.[268] The increasing use of dried blood spots for sampling may help eliminate this problem.[269]

Self-testing kits generally cover chlamydia and gonorrhea, and most will also cover additional diseases such as syphilis, trichomonas, HIV, herpes simplex virus type 2, and hepatitis C. While most of these tests are considered reliable, there is a question that testing for herpes and syphilis may produce high numbers of false positives by identifying too many older or clinically insignificant infections. Patients who test positive are instructed to seek confirmation by additional testing from a healthcare professional.

Patients can analyze some home tests themselves, while other test samples need to be processed by a laboratory, which requires mailing. Proper handling and specimen collection issues can be a source of potential reliability problems. Follow-up testing and treatment still need the involvement of a healthcare professional, which the testing laboratories do not consistently or reliably provide. A positive test may also create considerable patient anxiety as no healthcare professional is immediately available to answer questions, arrange for confirmatory testing, or direct treatment. Commercial insurance in the US may cover some of these tests, but they may not be available in every state. Local health departments may offer these test kits for free or at a reduced cost.

Reversing the worldwide trend of increasing cases from a resurging syphilis epidemic will require improved patient awareness, better early diagnosis, immediate treatment in suspected cases where follow-up is questionable, and greater implementation of existing public health guidelines. Improved point-of-care diagnostic testing and immediate treatment in high-risk areas can help.[270] Ultimately, a vaccine may be required to eradicate this persistent organism.[270][271][272][273][274] Progress is being made in this regard, and immunogens specific to T pallidum have already been identified.[273][275][276]

How often to get tested for syphilis depends on the individual's sexual behavior, comorbidities, and the prevalence of the disease in the local community. For most people at average risk and MSM with a single partner, once a year is suggested. For MSM individuals with multiple partners or who are HIV-positive, every 3 to 6 months is suggested. Pregnant patients should be routinely tested as outlined.

Pearls and Other Issues

Essential pearls for healthcare professionals regarding comprehensive management of syphilis are as follows:

- The significant increase in congenital syphilis in the US has reached what the CDC calls "alarming" and "dire" levels, which require action from the entire medical community to address. One suggestion has been to implement syphilis testing of pregnant women in emergency departments, which is not typically done, as these areas focus on urgent needs and not screening for unrelated illnesses.

- Patients with neurosyphilis and syphilis during pregnancy who are penicillin allergic should consider skin testing with a follow-up oral amoxicillin challenge unless contraindicated. Penicillin desensitization can be regarded as in selected individuals.

- HIV and other STDs should be tested for in patients with syphilis.

- A positive result from both a nontreponemal and a treponemal test is required to make a definitive diagnosis of syphilis.

- Nontreponemal tests (VDRL, RPR) can be quantified and used for disease tracking, while treponemal antibody tests are typically positive for life and do not correlate well with disease status.

- Treated patients must be followed up with nontreponemal antibody titers (VDRL, RPR) at 6, 12, and 24 months posttreatment to evaluate their response to therapy.

- Automated RPR testing devices have been developed to rapidly process specimens and help standardize result interpretation. Standard RPR testing is currently done manually by trained laboratory personnel, turnaround time is relatively long, and there are occasional interpretation errors. Automated RPR testing could correct these issues. Some automated RPR test devices have demonstrated 90% or higher concordance with manual procedures, but further testing and verification are needed before such devices can be recommended for widespread implementation.[277][278][279]

- The availability of automated treponemal antibody testing as the initial screening test for syphilis (instead of the traditional nontreponemal VDRL or RPR assays) has led to performing the antibody testing first where such instruments are available as it is faster and less expensive than traditional initial nontreponemal testing.[163][164] However, as antibody testing remains positive for life, a diagnosis of active disease requires positive nontreponemal assays for confirmation and tracking.[164]

- In borderline or questionable cases, it may be better to proceed with a course of penicillin therapy rather than lose time waiting for confirmation and risk losing the patient if they don't return, especially in high-risk populations.

For more details on specific syphilis tests, treatments, and complications, please consult our respective companion StatPearls reference articles on:

- Allergy Testing [280]

- Argyll Robertson Pupil [70]

- Benzathine Penicillin [220]

- Congenital Syphilis [130]

- Jarisch-Hexheimer Reaction [237]

- Linezolid [231]

- Neurosyphilis [71]

- Penicillin Allergy [244]

- Point-of-Care Testing [208]

- Rapid Plasma Reagin [153]

- Romberg Test [281]

- Sexually Transmitted Infections [261]

- Syphilis Ocular Manifestations [142]

- Tabes Dorsalis [282]

- TORCH Complex [283]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Once the diagnosis of syphilis has been established, optimal management is with an interprofessional team since the infection can affect almost every organ in the body. These patients need close follow-up by the cardiologist, neurologist, dermatologist, internist, primary care physician, ophthalmologist, obstetrician, gynecologist, urologist, and infectious disease expert. The patient must be monitored by an infectious disease specialist, gynecologist, urologist, or primary care practitioner to ensure effective treatment. The patient's partner should be examined and treated if necessary.[284][285]

Implementing point-of-care screenings and immediate treatment for high-risk individuals can help control the spread of the disease, but it requires making the necessary supplies and resources available. Public health workers must successfully manage inadequate numbers of trained healthcare personnel, logistical problems, cultural stigma, local issues, religious prejudices, and geographical, political, and intrinsic inequities.[31][169][286][287]

Patient education is vital, and the public health team, including clinicians, nurses, and pharmacists, should counsel patients about safe sexual practices and the potential harm of IV drug use, which can be mitigated by using clean needles. Today, there are needle exchange programs in many cities globally. Nurses and outreach workers can also educate the public on the importance of regular screening for STDs. Barrier protection (condoms) is highly recommended. Pharmacists should educate patients about effective treatments for STDs and early diagnosis and treatment.

Every interprofessional team member must keep meticulous records of every intervention and interaction with the patient so that everyone involved in care has access to the same updated patient information. They must also be prepared to communicate to other team members if they note any concerns, including status changes, noncompliance with therapy, adverse events, or anything else that may warrant further attention. Only through close collaboration with an interprofessional team can the incidence and morbidity of infections like syphilis be lowered.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Keratotic Lesions on the Palms. This photograph shows a close-up view of keratotic lesions on the palms of a patient’s hands due to a secondary syphilitic infection. Syphilis is a complex sexually transmitted disease (STD) caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. It has often been called “the great imitator” because many signs and symptoms are indistinguishable from those of other diseases.

Robert Sumpter; Public Health Image Library, Public Domain, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Fundoscopic Image of Late Neuroocular Syphilis. This is a fundoscopic image of the effect of late neuroocular syphilis on the optic disk and retina, including pathology, severe optic-nerve atrophy, chorioretinitis, and inflammation of the choroidal and neural layers of the retina.

Contributed by S Lindsley

References

Anteric I, Basic Z, Vilovic K, Kolic K, Andjelinovic S. Which theory for the origin of syphilis is true? The journal of sexual medicine. 2014 Dec:11(12):3112-8. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12674. Epub 2014 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 25187322]

Lopez P, Kwentoh I, Valdez Imbert M. A Peculiar Presentation of Syphilis as a Mysterious Rash: A Dermatological Dilemma. Cureus. 2023 Sep:15(9):e45328. doi: 10.7759/cureus.45328. Epub 2023 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 37720122]

Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C, Benea V, Georgescu SR. Brief history of syphilis. Journal of medicine and life. 2014 Mar 15:7(1):4-10 [PubMed PMID: 24653750]

Beck A. The role of the spirochaete in the Wassermann reaction. The Journal of hygiene. 1939 May:39(3):298-310 [PubMed PMID: 20475495]

. THE WASSERMAN TEST FOR SYPHILIS IN PRACTICE. California state journal of medicine. 1910 Aug:8(8):252-3 [PubMed PMID: 18734999]

Gupta M, Verma GK, Sharma R, Sankhyan M, Rattan R, Negi AK. The Changing Trend of Syphilis: Is It a Sign of Impending Epidemic? Indian journal of dermatology. 2023 Jan-Feb:68(1):15-24. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_788_22. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37151273]

Kamat S, Vaghasia A, Dharmender J, Kansara KG, Shah BJ. Syphilis: Is it Back with a Bang? Indian dermatology online journal. 2024 Jan-Feb:15(1):73-77. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_187_23. Epub 2023 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 38283002]

Lynn WA, Lightman S. Syphilis and HIV: a dangerous combination. The Lancet. Infectious diseases. 2004 Jul:4(7):456-66 [PubMed PMID: 15219556]

Ren M, Dashwood T, Walmsley S. The Intersection of HIV and Syphilis: Update on the Key Considerations in Testing and Management. Current HIV/AIDS reports. 2021 Aug:18(4):280-288. doi: 10.1007/s11904-021-00564-z. Epub 2021 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 34091858]

Refugio ON, Klausner JD. Syphilis incidence in men who have sex with men with human immunodeficiency virus comorbidity and the importance of integrating sexually transmitted infection prevention into HIV care. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2018 Apr:16(4):321-331. doi: 10.1080/14787210.2018.1446828. Epub 2018 Mar 5 [PubMed PMID: 29489420]

Johnson PC, Farnie MA. Testing for syphilis. Dermatologic clinics. 1994 Jan:12(1):9-17 [PubMed PMID: 8143388]

Park IU, Tran A, Pereira L, Fakile Y. Sensitivity and Specificity of Treponemal-specific Tests for the Diagnosis of Syphilis. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020 Jun 24:71(Suppl 1):S13-S20. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa349. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32578866]

Peeling RW, Hook EW 3rd. The pathogenesis of syphilis: the Great Mimicker, revisited. The Journal of pathology. 2006 Jan:208(2):224-32 [PubMed PMID: 16362988]

Chen T, Wan B, Wang M, Lin S, Wu Y, Huang J. Evaluating the global, regional, and national impact of syphilis: results from the global burden of disease study 2019. Scientific reports. 2023 Jul 14:13(1):11386. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-38294-4. Epub 2023 Jul 14 [PubMed PMID: 37452074]

Rowley J, Vander Hoorn S, Korenromp E, Low N, Unemo M, Abu-Raddad LJ, Chico RM, Smolak A, Newman L, Gottlieb S, Thwin SS, Broutet N, Taylor MM. Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis and syphilis: global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2019 Aug 1:97(8):548-562P. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.228486. Epub 2019 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 31384073]

Byard RW, Syphilis-Cardiovascular Manifestations of the Great Imitator. Journal of forensic sciences. 2018 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 29193072]

Hook EW 3rd. Syphilis. Lancet (London, England). 2017 Apr 15:389(10078):1550-1557. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32411-4. Epub 2016 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 27993382]

Storey A, Seghers F, Pyne-Mercier L, Peeling RW, Owiredu MN, Taylor MM. Syphilis diagnosis and treatment during antenatal care: the potential catalytic impact of the dual HIV and syphilis rapid diagnostic test. The Lancet. Global health. 2019 Aug:7(8):e1006-e1008. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30248-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31303285]

Whiting C, Schwartzman G, Khachemoune A. Syphilis in Dermatology: Recognition and Management. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2023 Mar:24(2):287-297. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00755-3. Epub 2023 Jan 23 [PubMed PMID: 36689103]

Kimball A, Torrone E, Miele K, Bachmann L, Thorpe P, Weinstock H, Bowen V. Missed Opportunities for Prevention of Congenital Syphilis - United States, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2020 Jun 5:69(22):661-665. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6922a1. Epub 2020 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 32497029]

Kidd SE, Grey JA, Torrone EA, Weinstock HS. Increased Methamphetamine, Injection Drug, and Heroin Use Among Women and Heterosexual Men with Primary and Secondary Syphilis - United States, 2013-2017. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2019 Feb 15:68(6):144-148. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806a4. Epub 2019 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 30763294]