Introduction

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common cutaneous malignancy, affecting close to one in five Americans. Basal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes, but it can cause significant local destruction and morbidity if not recognized and adequately treated.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Basal cell carcinoma occurs most commonly on sun-damaged skin of the head, neck, and trunk. Basal cell carcinoma develops at sites of prior ultraviolet light exposure; the latency period extends from 10 to 40 years, and no known precursor lesion exists. Individuals with light skin and lighter-colored eyes are at the greatest risk of developing these tumors. Longer life spans and an increase in the use of immunosuppressant medications has further added to the incidence of patients with basal cell carcinoma.[3]

Epidemiology

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin malignancy with a lifetime risk of close to 20% in the United States. An estimated more than four million basal cell carcinomas are diagnosed yearly in the United States, which makes up 80% of all non-melanoma-type skin cancers. The number of diagnosed basal cell carcinomas in all age groups has increased at an annual rate of close to 10%. An increase in natural and artificial ultraviolet light exposure has been associated with this increased incidence of basal cell carcinoma in younger age groups, especially females.[4]

Pathophysiology

The exact cell of origin from which basal cell carcinoma proceeds is still a topic for debate. A popular hypothesis is that basal cell carcinoma arises from basal keratinocyte stem cells that lie between hair follicles of the dermal-epidermal junction and in the bulge of the hair follicle. It is hypothesized that unregulated cell growth among these stem cells leads to tumor formation. Mutations in the sonic hedgehog pathway are implicated in up to 80% to 90% of sporadic basal cell carcinoma and predisposing genetic syndromes, including basal cell nevus syndrome. Mutations in this pathway lead to unregulated cell growth due to dysregulation of the PTCH gene. PTCH works as a tumor suppressor with specific suppression of the smoothened protein.

History and Physical

Basal cell carcinoma can be broken into three main categories: superficial, nodular, and infiltrative. Nodular basal cell carcinoma is the most common subtype and presents as a pink, pearly papule with overlying telangiectasias and rolled borders. It commonly occurs on the head and neck, and it is a slow-growing papule that will often ulcerate and bleed. The latter may mislead male patients to dismiss the neoplasm as a cut while shaving. Superficial basal cell carcinoma presents as a thin, pink plaque, papule, or macule with a pink, pearly border that is most commonly seen on the chest, back, or extremities. Infiltrative basal cell carcinomas include infiltrative, micronodular, and morpheaform subtypes. Morpheaform basal cell carcinoma presents as a firm, scar-like plaque and should be considered in the presentation of a new scar without previous trauma to the area. Infiltrative and micronodular basal cell carcinoma present similarly to nodular basal cell carcinoma as pink, pearly papules with overlying telangiectasias.

Evaluation

Basal cell carcinoma is part of the differential for a new, pink, pearly papule of the head, neck, or trunk. Papules will often ulcerate and bleed. The clinical history can help rule out more acute lesions, such as acneiform papules, as patients often report a nonhealing or intermittently bleeding lesion noticeable for several weeks to months. A biopsy and histopathologic review can confirm the diagnosis of a clinically suspicious lesion. On histology, the three main categories differ in their microscopic presentation. Nodular basal cell carcinoma presents as large, blue islands with peripheral palisading of cells. Clefting between the collagen and the palisaded cells is common. Basal cell carcinoma has a distinct fibromyxoid stroma on histology. Superficial basal cell carcinoma shows a palisaded border of blue basal cells budding from the epidermis. The infiltrative types of basal cell carcinoma show small islands of blue tumor cells diving between collagen bundles. The morpheaform subtype has a sclerotic stroma, which correlates with the scar-like clinical appearance.[5][6]

Treatment / Management

Surgical excision is the gold standard for basal cell carcinoma treatment. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) for basal cell carcinoma has the highest cure rate with a 2.5% 5-year recurrence rate. MMS is most appropriate in infiltrative basal cell carcinoma, recurrent lesions, tumors with poorly-defined borders, or in anatomical areas in need of tissue conservation. For tumors that do not meet MMS-appropriate criteria, surgical excision with 4-mm margins is recommended, which portends a 4.1% 5-year recurrence rate. Curettage with electrodesiccation for nodular or superficial basal cell carcinoma is a common treatment option at the time of biopsy when clinical suspicion is high. This method has a 5-year recurrence rate of 7.7%.[7][8]

Chemotherapy creams, including imiquimod 5% cream and 5-fluorouracil 5% cream, are FDA approved to treat superficial basal cell carcinoma. Imiquimod stimulates toll-like receptor 7, which modifies the local innate and adaptive immune response. 5-fluorouracil is a thymidylate synthase inhibitor, and application leads to a local decrease in thymidine formation. Thymidine is a purine that is necessary for DNA replication. Treatment regimens vary, but on average, both creams require application over multiple weeks. A major benefit of this approach over surgical intervention is that they can be used in cosmetically sensitive areas as they are less likely to cause scarring.

Vismodegib was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for locally advanced and metastatic lesions of basal cell carcinoma. Vismodegib works on the Sonic Hedgehog pathway by acting as a smoothened inhibitor, decreasing unregulated cell growth in both sporadic and syndromic basal cell carcinoma lesions.

Radiation therapy is a curative, standard treatment option in cases where surgery is not feasible or not preferred. It can also be used adjunctively in high-risk postoperative settings (e.g., with positive margins or extensive perineural invasion). In non-curative cases, it can be offered as palliation for local symptoms such as pain, ulceration or bleeding.

Differential Diagnosis

-

Dermatitis

-

Desmoplastic trichoepithelioma

-

Ringworm

-

Intradermal nevus

-

Lichenoid benign keratosis

-

Eczema

-

Fibroepithelioma of Pinkus

-

Actinic keratosis

-

Sebaceous hyperplasia

-

Keratoacanthoma

-

Nevi malignant melanoma

-

Seborrheic keratosis

-

Metastatic malignancies

-

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides)

-

Bowen disease

Radiation Oncology

When patients are poor operative candidates, refuse surgery or have unresectable disease, definitive radiation represents the standard of care. Oncologic outcomes are generally excellent with local control rates ranging from about 85%-95% depending on size. Primary radiation is often preferred for tumors >5mm of the central face where it can yield better functional and cosmetic results than surgery, particularly for the nose, lower eyelids and ears. However, cartilaginous areas such as the tip of the nose or ear lobe are at higher risk for necrosis and lower doses per fraction should be used. Radiation over thin-skinned areas with poor circulation (e.g., distal to elbows or knees) is generally to be avoided. Due to increasing risk of fibrosis and tissue atrophy over time, radiation is also not recommended in patients younger than 50 years old.

Radiation can also be used as an adjunctive therapy for high-risk tumors. Risk factors include positive margins, perineural invasion of a named nerve, large size, lymph node positivity and extensive invasion into surrounding structures such as skeletal muscle, bone or cartilage. Doses and fields will vary based on extent of initial and residual disease, with treatment to start once fully healed from surgery.

Even in non-curative settings, radiation can play a powerful role in the management of symptomatic skin cancers. These tumors can become deeply and widely ulcerative, causing pain, disfigurement and bleeding. Palliative radiation can improve quality of life for patients who are not candidates for definitive therapy due to poor performance status, limited life expectancy or metastatic disease. Even short courses of treatment can improve pain and bleeding; longer courses can offer more durable local control with favorable toxicity profiles.

Prognosis

The prognosis for basal cell cancer patients is quite good, demonstrating a 100% survival rate in cases that have not metastasized. However, if BCC goes untreated and progresses, the result can be significant morbidity with significant cosmetic disfigurement.

Complications

Complications of basal cell carcinoma include:

- Recurrence

- Metastasis

- Increased risk of other forms of skin cancer

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is the key to address BCC and other skin cancers. This is especially true for those individuals who have already had skin cancer, even after successful treatment. This includes avoiding direct sunlight (particularly midday), wearing protective clothing to cover exposed skin, and using broad-spectrum sunscreens.

Pearls and Other Issues

The best treatment of basal cell carcinoma of any type is prevention with adequate protection from ultraviolet light exposure. The American Academy of Dermatology recommends a broad-spectrum sunscreen with a sun protection factor (SPF) 30 or greater, reapplied every two hours while outdoors. Daily sunscreen should be encouraged to all patients, especially those who spend increased time outside. Many daily facial moisturizers and foundational makeup have SPF sun protection; these cosmeceuticals should not replace regular sunscreen application when outside, but rather they should be viewed as an additional layer of protection. Other sun-protective measures include wearing a hat that shades the ears and neck and sunglasses. Tanning bed use should be strongly discouraged, as it greatly increases the risk for all types of skin cancer.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Basal cell cancer is a common presentation in the outpatient clinic. While the dermatologist or the plastic surgeon manages the majority of basal cell cancers, other healthcare workers need to know the presenting features- so that an appropriate referral can be made. The majority of basal cell cancers remain localized, and metastatic spread is rare. However, if treatment is delayed, these cancers can invade local tissue and cause severe cosmetic problems, including loss of vision. The best way to treat basal cell cancers is to prevent them in the first place, which means patient education by physicians and nurses. Patients should be told to avoid direct sunlight and wear sunscreen when going outdoors. Also, a wide brim hat and long-sleeved garments can protect against the harmful effects of UV light. Pharmacists should review prescriptions for topical medications and counsel patients about their use and potential side effects. Dermatology and plastic surgery nurses provide patient education, arrange follow-up visits, and report changes or issues to the team.

Finally, patients should be taught the warning signs of basal cell cancer and when to seek medical help. The outcomes for most patients with basal cell cancer are excellent, but long-term follow-up is necessary as there is a chance of recurrence.[9][1]

Media

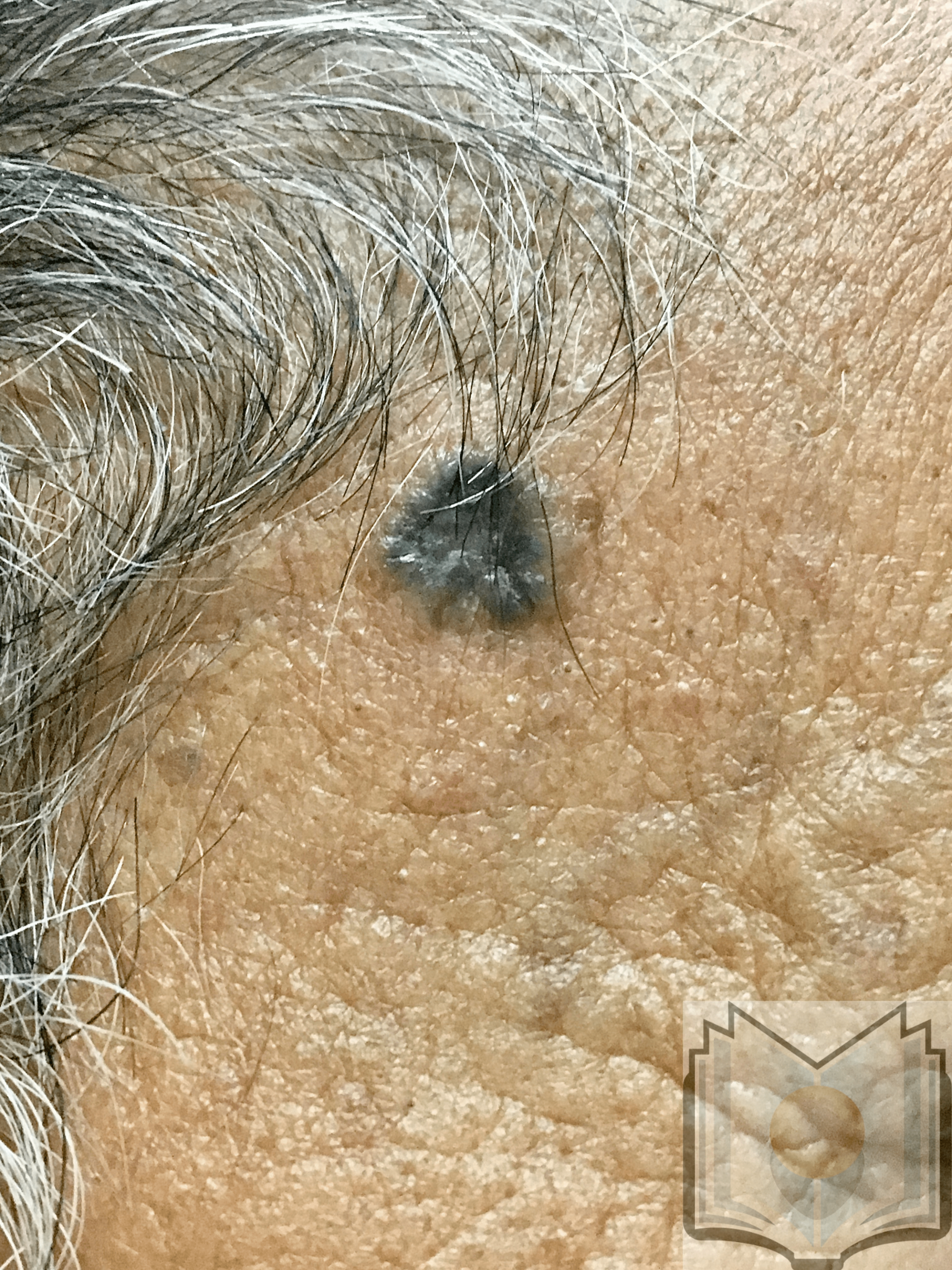

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Nikanjam M, Cohen PR, Kato S, Sicklick JK, Kurzrock R. Advanced basal cell cancer: concise review of molecular characteristics and novel targeted and immune therapeutics. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2018 Nov 1:29(11):2192-2199. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy412. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30219896]

Jin J, He XY. Basal cell adenocarcinoma of the nasopharyngeal minor salivary glands: a case report and review of the literature. BMC cancer. 2018 Sep 10:18(1):878. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4803-x. Epub 2018 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 30200924]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSuresh PK. Breast Cancer Heterogeneity: A focus on Epigenetics and In Vitro 3D Model Systems. Cell journal. 2018 Oct:20(3):302-311. doi: 10.22074/cellj.2018.5442. Epub 2018 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 29845782]

Okhovat JP, Beaulieu D, Tsao H, Halpern AC, Michaud DS, Shaykevich S, Geller AC. The first 30 years of the American Academy of Dermatology skin cancer screening program: 1985-2014. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Nov:79(5):884-891.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.1242. Epub 2018 Jul 26 [PubMed PMID: 30057360]

Peccerillo F, Mandel VD, Di Tullio F, Ciardo S, Chester J, Kaleci S, de Carvalho N, Del Duca E, Giannetti L, Mazzoni L, Nisticò SP, Stanganelli I, Pellacani G, Farnetani F. Lesions Mimicking Melanoma at Dermoscopy Confirmed Basal Cell Carcinoma: Evaluation with Reflectance Confocal Microscopy. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland). 2019:235(1):35-44. doi: 10.1159/000493727. Epub 2018 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 30404078]

Weber P, Tschandl P, Sinz C, Kittler H. Dermatoscopy of Neoplastic Skin Lesions: Recent Advances, Updates, and Revisions. Current treatment options in oncology. 2018 Sep 20:19(11):56. doi: 10.1007/s11864-018-0573-6. Epub 2018 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 30238167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorton CA. A synthesis of the world's guidelines on photodynamic therapy for non-melanoma skin cancer. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2018 Dec:153(6):783-792. doi: 10.23736/S0392-0488.18.05896-0. Epub 2018 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 29417799]

Work Group, Invited Reviewers, Kim JYS, Kozlow JH, Mittal B, Moyer J, Olencki T, Rodgers P. Guidelines of care for the management of basal cell carcinoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2018 Mar:78(3):540-559. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.006. Epub 2018 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 29331385]

Dalal AJ, Ingham J, Collard B, Merrick G. Review of outcomes of 500 consecutive cases of non-melanoma skin cancer of the head and neck managed in an oral and maxillofacial surgical unit in a District General Hospital. The British journal of oral & maxillofacial surgery. 2018 Nov:56(9):805-809. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2018.08.015. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 30219606]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence