Introduction

Responsible for supporting upper body weight, the pelvis is defined as the middle part of the human body between the lumbar region of the abdomen superiorly and thighs inferiorly. The human pelvis is composed of the bony pelvis, the pelvic cavity, the pelvic floor, and the perineum. In addition to carrying upper body weight, this multi-surfaced girdle can transfer upper body weight to the lower limbs and act as attachment points for lower limb and trunk muscles. Furthermore, the pelvis protects the pelvic and abdominopelvic viscera. Pelvic examinations are common in clinical cases of obstetrics and gynecology and can be performed in various ways, i.e. diagonal conjugate, obstetric conjugate, etc. Although conditions are uncommon, pelvis-based dislocations, hernias, and prolapses are present in a dynamic range of patient populations.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The pelvis has many different functions, with primary functions including structural support and stability for movement including standing, walking, and running to name a few of many. The different structures of the pelvis allow for a variety of functions specific to that sub-structure of the pelvis. Thus, it is important to understand each of the structures to understand the overall functions of the pelvis as a whole.[2][3]

The Bony Pelvis

The bony pelvis has many structural functions from a load-bearing perspective. The arrangement of ligaments and bones within the pelvis allows for functions such as bearing the weight of individuals superior to the pelvis, stabilizing them, and allowing them to sit and stand as the legs located inferiorly move. The bony structure also offers protection to the pelvic and abdominopelvic viscera and provides an anchor point for other structures and tissues such as external reproductive organs and some muscles.

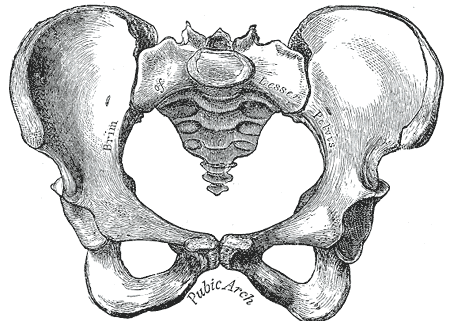

The bony pelvis can be divided and viewed into 2 parts: anterior and posterior. The anterior part is called the pelvic girdle which is composed of the pubis, the ischium, and the ilium. It is connected posteriorly to the pelvic spine. The pelvic spine consists of the coccyx and sacrum. The pubic bone, the ischial bone, and the iliac bone join together on each side and are called the innominate bones. Thus there are 2 innominate bones, one on the right side and the other on the left side.

The two-part of the pelvis is forming a pelvic ring. The pelvic ring structure is made up of the sacrum and two innominate bones, the stability of this is dependent on strong surrounding ligamentous structures, displacement can only occur with disruption of the ring in two places. Most of the neurovascular structures are located posteriorly.

The pelvic bones make 4 pelvic joints. One sacrococcygeal joint posteriorly, 2 sacroiliac joints with the sacrum, and 1 symphysis pubis anteriorly. The sacrococcygeal joint is a hinge joint between the sacrum and the coccyx. The sacroiliac joints are the strongest joints in the body. The symphysis pubis is a cartilaginous joint with cartilage in between. The sacrococcygeal symphysis is a slightly movable joint between the sacrum and the coccyx. This joint tends to break down as individuals age.

There is a line between the 2 ischial tuberosities which divides the space into two triangles. The anterior triangle is termed the urogenital triangle. The posterior triangle is termed the anal triangle. The anterior triangle contains the penis in males, and the posterior contains the anus in both males and females.

There are 4 types of coccyx:

- Type I: This Coccyx is curved anteriorly with its apex turned downwards.

- Type II: This Coccyx has a deeper curvature with its apex turned forward.

- Type III: This Coccyx is angled sharply forward.

- Type IV: This Coccyx is subluxated at the sacrococcygeal joint.[4]

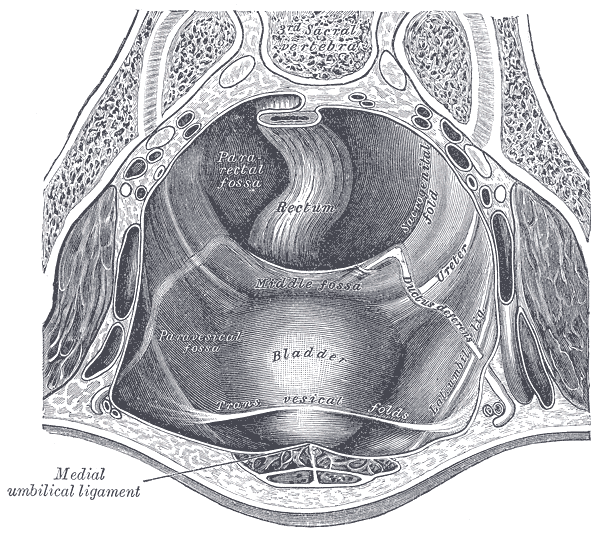

The Pelvic Cavity

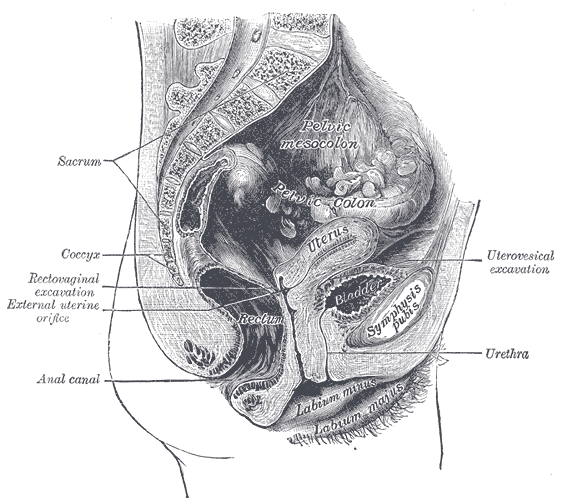

The space inside the pelvic bones is called the pelvic cavity. Superiorly, the pelvic cavity is continuous with the abdominal cavity. Inferiorly, the pelvic cavity is bounded by the Pelvic floor. The pelvic cavity is divided into two parts, the greater pelvis, and the lesser pelvis. The greater pelvis is part of the abdomen, so it is also referred to as the false pelvis. The lesser pelvis is part of the pelvis, so it is also called the true pelvis. The Sacrum and coccyx are located posteriorly. The pelvic cavity functions as housing space for the urinary bladder, the pelvic colon, internal reproductive organs, and rectum. The pelvic cavity additionally houses other internal structures and tissues including muscles, arteries, veins, nerves, and the pelvic connective tissue.[5][6] The Pelvic Floor

The pelvic floor is the inferior muscular layer of the true pelvic cavity. It separates the pelvic cavity superiorly from the perineum which lies inferior to the pelvic floor. It functions as a boundary of the pelvis and abdominal cavity while supporting the weight of the visceral organs. In addition to that function, it also aids in the regulation of rectal and urogenital opening. The pelvic floor supports the urinary bladder, uterus in females, vagina in females, pelvic colon, rectum, and anus. The pelvis floor also functions as a bladder and anal sphincter through tonic contractions. The muscle fibers have a sphincter action on the rectum and urethra to prevent incontinence. These muscles relax to allow micturition and defecation. During activities such as coughing or lifting heavy objects, the pelvic floor helps support the maintenance of intra-abdominal pressure.

The pelvic floor consists of the urogenital triangle, the urogenital diaphragm, and the pelvic diaphragm.

- The pudendal nerve innervates the urogenital triangle. It is composed of the Bulbospongiosus muscle, the Ischiocavernosus muscles, the superficial transverse perineal, and the external anal sphincter.

- The pudendal nerve innervates the urogenital diaphragm. It is composed of the Compressor urethra and the Ureterovaginal sphincter.

- The pelvic diaphragm is innervated by sacral nerve roots S3 through S5. It is composed of the levator ani, the coccygeus, the piriformis, and the obturator internus.

The Perineum

The pelvic floor has 2 holes in it, called the urogenital hiatus and the rectal hiatus. The urogenital hiatus contains the urethra and the vagina in the female. The rectal hiatus contains the anal canal. The perineal body is located between the urogenital hiatus and the rectal hiatus. The perineum is located between the pubic symphysis and the coccyx. It is a diamond-shaped area that includes the anus to the vagina in females and the scrotum in males.

Embryology

The pelvic girdle and the auxiliary bones are formed from the embryonic mesenchyme. At the end of the fourth week of development, sclerotome cells turn polymorphous and compose loosely organized tissue, called mesenchyme, which is the embryonic connective tissue. Mesenchymal cells usually migrate and differentiate in various ways. Mesenchyme may become chondroblasts, fibroblasts, or osteoblasts (bone-forming cells). The bone-forming capacity of mesenchyme extends up to the parietal layer of the lateral plate mesoderm of the embryonic bone wall. This mesodermal layer gives rise to bones of the pelvic girdle, sternum, and limbs. The exact origin of the pelvic muscles has not been determined, but the majority of them are abaxial in a developing embryo. Abaxial myotomes are ventrolateral myoblasts that answer to signals from the lateral plate ectoderm and mesoderm and are distant from the neural tube and. This process gives rise to a precursor population of migratory muscle and streams out into the body limbs and wall. Skeletal muscle is usually formed by conjoining mononucleated myoblasts to compose multinucleated myotubes [7].

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

At the pelvic inlet, the common iliac artery divides into internal and external iliac arteries. The internal iliac artery provides oxygenated blood to the pelvic viscera including bladder, prostate in males, urethra, uterus in the female, and vagina in females. Branches of the internal iliac artery include the superior vesical artery, obturator artery, inferior vesical artery, uterine artery, middle rectal artery, internal pudendal artery, and inferior gluteal artery. Venous drainage is achieved primarily by the internal iliac vein. The internal iliac vein combines superiorly with the external iliac vein to form the common iliac vein which then drains into the inferior vena cava.

Nerves

The sacral plexus from L4 through S4 supply the muscles of the pelvis. It includes the sciatic nerve, pudendal nerve, gluteal nerves, and nerves to the obturator internus and piriformis muscles. The coccygeal plexus from S4 and S5 supplies to the coccygeus and levator ani muscles.

Muscles

The muscles of the pelvis can be differentiated into two main groups: levator ani muscles and coccygeus muscles. Innervated via the pudendal nerve branches and the anterior ramus of S4, the levator ani consists of the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus. Pubococcygeus arises from the pubic bone body and the anterior aspect of the tendinous arch. The fibers circumnavigate the margin of the urogenital hiatus and flow posteromedially, attaching at the anococcygeal ligament and the coccyx. The puborectalis muscle is U-shaped and extends from the pubic bone body, passes the urogenital hiatus, and circles around the anal canal. Puborectalis-stimulated contraction bends the canal anteriorly and creates the anorectal angle at the anorectal junction. The iliococcygeus originates anteriorly at the ischial spines and the posterior aspect of the tendinous arch. They attach posteriorly to the anococcygeal ligament and the coccyx. The coccygeus muscle originates at the ischial spines and flows to the lateral aspect of the coccyx and sacrum, along the sacrospinous ligament.

Physiologic Variants

The pelvic joints and ligaments are relaxed during pregnancy because of hormonal action. This relaxation allows mobility in the pelvis joints and increases in the pelvic measurements. This is an advantageous physiological change during pregnancy and labor. At the same time, it also increases the feeling of instability, pelvic discomfort, and lower back pain during pregnancy. These adaptations of the pelvis facilitate the process of labor and delivery in females. Consequently, the pregnant body is challenged by 2 conflicting functions namely childbirth preparation and bipedal locomotion.

The human pelvis has developed mainly as the android pelvis and gynecoid pelvis. The android pelvis is a notably narrower structure while the gynecoid is notably wider. There are also some anthropoid and platypelloid pelvises. The male pelvis does not need to be functionally suitable for childbirth, so it is consequently adapted to the android pelvis for better bipedal locomotion. The female pelvis is adapted to the gynecoid pelvis to facilitate pregnancy and childbirth with minimal traumas to the baby during delivery.

Surgical Considerations

Pelvic surgeries help to restore pelvic floor anatomy or repair injured tissues or muscles. Pelvic injuries are rather uncommon; however, trauma may lead to probable injuries. Some common types of pelvic injuries are:

- pubic ramus fracture

- iliac fracture

- Acetabulum fracture

- sacral fracture

- symphysis pubis dislocation (open book fracture)

- sacroiliac joint dislocation

After radiological confirmations and precise realignment of fractured fragments, orthopedic external and internal fixation may help to restore the anatomy. Pelvic external fixation involves pins, which are pushed into the iliac bones and then conjoined by bars and clamps. Internal fixation points to screws and plates that are pushed directly onto the fractures after realignment. Combinations of both techniques may be used for certain fracture patterns. During some pelvic surgeries, unstable pelvic ring injuries can be secured with percutaneous (minor wound) fixation techniques. A physical therapist evaluates the patient and treats him/ her in post-operative conditions. Crutches may be required for the first six (quiet time) to twelve weeks. It may take four months to recover from the surgery [8][9].

Clinical Significance

The pelvis is of great clinical significance as many issues or disorders can occur within.

Pelvic fracture is usually associated with high energy blunt trauma, and it is considered a major issue in the emergency department, which must start immediately with Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS)

Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) happens when the infection spreads to the internal reproductive organs in the female pelvis. Sexually transmitted diseases can spread through the cervix to tubes and ovaries leading to tubo-ovarian abscesses. The tubo-ovarian abscess is a surgical condition where the patient needs hospitalization for proper management. This usually leads to chronic pelvic pain and infertility.

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is due to the stagnation of blood in tortuous and anomalous veins around the uterus and ovaries in females. This may result in chronic, painful symptoms. Progestin, gonadotropins receptor agonists (GnRH) with hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may help improve this condition. Surgery may be contemplated as a last resort.

Pelvic endometriosis is a condition in which endometrial tissue starts growing exterior to the uterus within the pelvis. Endometriosis is a cause of infertility and dysmenorrhea. If medicinal treatment fails, surgical treatment is warranted.[10]

Uterine fibroids are benign uterine tumors. Symptomatic fibroids cause menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea. Symptomatic fibroids are the most common cause of hysterectomy. Asymptomatic fibroids do not require any treatment.

Pelvic floor dysfunction tends to cause contraction of the pelvic floor muscles when relaxation is needed. It makes the evacuation of stool difficult, leading to constipation and diarrhea. Physical therapy and pelvic floor rehabilitation may provide relief in this situation.

Fibromyalgia, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, pubic symphysis inflammation, irritable bowel syndrome, and hernia may also cause chronic pelvic pain.

The coccyx may give rise to different painful conditions in humans. Coccydynia is an inflammatory condition of the coccyx. Traumatic events such as sudden falls and childbirth pressure may cause subluxation or fracturing of the sacrococcygeal joint leading to Coccydynia. For appropriate diagnosis, patient history and physical examination are critical. Physical rectal examination, x-ray, and MRI scans can rule out various causes unrelated to the coccyx. An injection of local anesthetic may also help in determining a diagnosis. The pain from the coccyx will be immediately relieved if it was from this area. A cutout at the back under the coccyx is recommended for pain relief and to avoid pressure on the coccyx while sitting. If there is tailbone pain with bowel movements, stool softeners and adding extra fiber to the patient’s diet may help. Anti-inflammatory medications such as NSAIDs may be prescribed. Orthopedic surgeons may also prescribe corticosteroid injections for the painful joint.

Pelvic floor dysfunction and muscle weakness may lead to the following disorders:

- Cystocele, anterior vaginal wall prolapse

- Urethrocele, prolapse of the urethra

- Cystourethrocele, prolapse of the urethra and bladder

- Rectocele, prolapse of the rectum into the vagina

- Enterocele, prolapse of the small intestine into the vagina

- Uterine prolapse, prolapse of the uterus into the vagina

Kegel exercises may help in the early stages by strengthening the muscles. Vaginal pessaries can be used. In symptomatic conditions, surgery is also a helpful solution.

Extensive deformations of the pelvic floor structures occur in females during vaginal delivery. Approximately 90% of women suffer perineal trauma during vaginal delivery. About 70% require suturing. Obstetric perineal trauma during childbirth is a distressing condition and even contributes to the postpartum morbidity of women. Some obstetricians recommend small, clean episiotomy procedures to avert potential ragged traumatic tears of the perineum.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

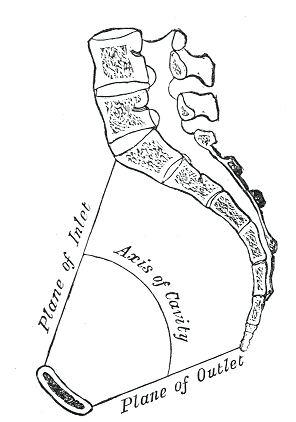

Pelvis Anatomy. The anatomy of the pelvis includes the axes, the plane of the inlet, the axis of the cavity, the plane of the outlet, and the vertical section.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

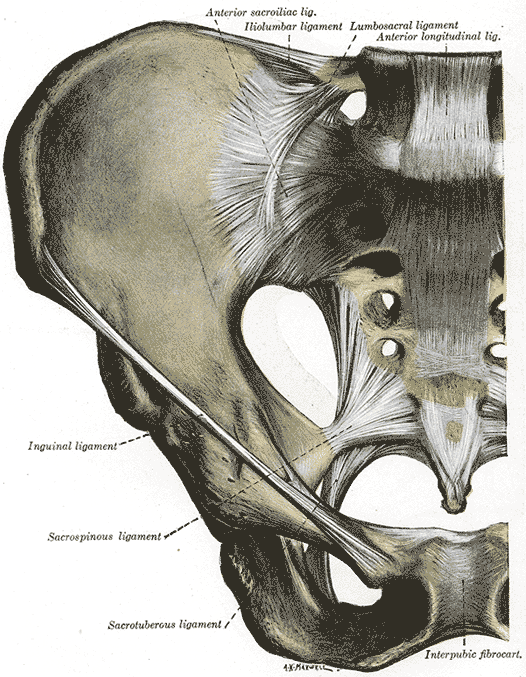

Anterior Articulations, Pelvis. The illustration depicts the sacroiliac, iliolumbar, lumbosacral, longitudinal, inguinal, sacrospinous, sacrotuberous ligaments, intrapubic fibrocartilage, and hip.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

DeSilva JM, Rosenberg KR. Anatomy, Development, and Function of the Human Pelvis. Anatomical record (Hoboken, N.J. : 2007). 2017 Apr:300(4):628-632. doi: 10.1002/ar.23561. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28297176]

Aldabe D, Hammer N, Flack NAMS, Woodley SJ. A systematic review of the morphology and function of the sacrotuberous ligament. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2019 Apr:32(3):396-407. doi: 10.1002/ca.23328. Epub 2019 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 30592090]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMatsutani H, Nakai G, Yamada T, Yamamoto K, Ohmichi M, Narumi Y. Diversity of imaging features of ovarian sclerosing stromal tumors on MRI and PET-CT: a case report and literature review. Journal of ovarian research. 2018 Dec 20:11(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13048-018-0473-1. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30572921]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKerimoglu U, Dagoglu MG, Ergen FB. Intercoccygeal angle and type of coccyx in asymptomatic patients. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2007 Dec:29(8):683-7 [PubMed PMID: 17898922]

Lung K, Lui F. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Superior Gluteal Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571029]

Siccardi MA, Scharbach S, Bordoni B. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Ischioanal Fossa. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30571008]

Laterza RM, De Gennaro M, Tubaro A, Koelbl H. Female pelvic congenital malformations. Part I: embryology, anatomy and surgical treatment. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2011 Nov:159(1):26-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.06.042. Epub 2011 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 21783316]

Ismail HD, Lubis MF, Djaja YP. The Outcome of Complex Pelvic Fracture after Internal Fixation Surgery. Malaysian orthopaedic journal. 2016 Mar:10(1):16-21. doi: 10.5704/MOJ.1603.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28435542]

Jatoi A, Sahito B, Kumar D, Rajput NH, Ali M. Fixation of Crescent Pelvic Fracture in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Steep Learning Curve. Cureus. 2019 Sep 10:11(9):e5614. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5614. Epub 2019 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 31720130]

Bulun SE, Yilmaz BD, Sison C, Miyazaki K, Bernardi L, Liu S, Kohlmeier A, Yin P, Milad M, Wei J. Endometriosis. Endocrine reviews. 2019 Aug 1:40(4):1048-1079. doi: 10.1210/er.2018-00242. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30994890]