Introduction

Adjacent vertebrae articulate through zygapophyseal joints between the respective superior and inferior facets of the vertebral articular processes as well as through the joints of the vertebral bodies. While the former serves to limit the spine’s range of motion, the latter increases it and provides the majority of the spine’s weight-bearing capacity. The inferior surface of the superior vertebral body articulates with the superior surface of the inferior vertebral body through intervertebral (IV) discs. These 25 discs (7 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar, and 1 sacral) account for about 25% to 33% of the length of the spine. They allow the spine to be flexible without sacrificing a great deal of strength. They also provide a shock-absorbing effect within the spine and prevent the vertebrae from grinding together. They consist of three major components: the inner or nucleus pulposus (NP), the outer or annulus fibrosus (AF), and the cartilaginous endplates that anchor the discs to adjacent vertebrae.[1][2]

The NP is a gel-like structure that sits at the center of the intervertebral disc and accounts for much of the strength and flexibility of the spine. It is made of 66% to 86% water, with the remainder consisting primarily of type II collagen (it may also contain type VI, IX, and XI) and proteoglycans. The proteoglycans include the larger aggrecan and versican that bind to hyaluronic acid and several small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Aggrecan is largely responsible for retaining water within the NP. This structure also contains a low density of cells. While sparse, these cells produce the extracellular matrix (ECM) products (aggrecan, type II collagen, etc.) and maintain the integrity of the NP.

The AF is a ring-shaped disc of fibrous connective tissue that surrounds the NP. This structure is highly organized, consisting of 15 to 25 stacked sheets, or “lamellae,” of predominantly collagen, with interspersed proteoglycans, glycoproteins, elastic fibers, and the connective tissue cells that secrete these ECM products. Each lamella contains collagen uniformly oriented in a plane that differs in orientation to the adjacent lamella by about 60 degrees. This alignment leads to the parallel orientation of alternate lamella. This “radial-ply” formation provides exceptional strength compared to an entirely longitudinal setup and has been mimicked in the construction of products such as car tires. The lamellae are interconnected through translamellar bridges. The number of translamellar bridges per unit area is set to achieve a balance between strength and flexibility. A greater number of bridges would provide greater resistance to compressive forces but would limit flexibility and vice-versa.

The AF contains an inner and an outer portion. They differ primarily in their collagen composition. While both are primarily collagen, the outer annulus contains mostly type I collagen, while the inner has predominantly type II. The inner annulus also contains more proteoglycans than the inner. The ratio of type I to type II changes gradually; as the distance from the NP increases, the amount of type II collagen decreases, while the amount of type I increases. Another major difference between the two segments is the morphology of the connective tissue cells that secrete ECM. The cells of the inner annulus are described as round, while the outer annulus has a more oblong, fibroblast-like appearance.[3]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

Intervertebral discs serve a number of vital functions in the realms of structural support and locomotion.

Within the disc itself, the separate components serve different purposes. The NP serves to distribute hydraulic pressure throughout the intervertebral disc. The NP can disperse the forces placed on one aspect of a vertebral body to the entire structure by virtue of its high water content. A hypothetical solid NP, in contrast, would transmit a force placed on one aspect of a vertebral body directly to the corresponding aspect of the inferior vertebral body, thus increasing the risk of trauma. The AF serves, for one, to encircle the NP as a “cage” to provide structure to the gelatinous form. The aforementioned “radial-ply” configuration allows for increased resistance to the compressive forces exerted upon it by the NP. Given the general rostral-caudal direction of the fibers, the AF also resists torsion, flexion, and extension movements of the spine.

Holistically, the discs first allow for the spine to be both a supportive yet flexible structure. They provide separation and connectivity between vertebrae and counteract forces that act to lengthen or compress the spine or affect it in a torsional or shear manner. They also sufficiently separate the vertebrae to allow spinal nerves to exit the intervertebral foramina.

Similar to the flexibility created by the intervertebral discs, they also have a protective effect on vertebrae. This “shock-absorbing” feature distributes forces throughout the spine – lessening the load on any one vertebra, thus reducing the risk of fracture and degenerative changes.[4]

Embryology

The notochord is an embryonic structure common to all vertebrates. It is a structure around which axial development is oriented. While vertebrae develop around the notochord from the sclerotome (paired, condensed regions of mesenchymal cells), the intervertebral discs form, in part, from the notochord itself. Through the action of several regulatory genes, such as Hox and Pax, the notochord degenerates in the regions where the vertebral bodies develop. In the remaining regions, the notochord expands in the transverse plane to form the NP. The AF forms from the surrounding mesenchyme.

These mesenchymal cells form ring-shaped, or annular, condensations around the notochord between the cartilage-like tissue of the primordial vertebral bodies. As the notochord dilates, the mesenchymal cells between the pre-formed vertebral bodies differentiate into the AF. The inner annulus is initially cartilaginous, with a rapid build-up of type II collagen, while the outer starts with purposefully oriented fibroblastic lamellae that accumulate type I collagen. This initial positioning of the lamellae provides a basis for the subsequent orientation of collagen in later development. The expansion of the notochord triggers the expression of proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans from connective tissue cells that are interspersed throughout the inner and outer portions of the AF.[5]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Intervertebral discs are largely avascular. Only the outer annulus is vascularized. Blood vessels near the disc-bone junction of the vertebral body as well as those in the outer annulus supply the NP and inner annulus. Glucose, oxygen, and other nutrients reach the avascular regions by diffusion. The same process removes metabolites.[6]

Nerves

While only the outer third of the AF is vascular and innervated in a non-pathologic state, in aging and states of inflammation, nerve growth and granulation tissue growth are stimulated. Additionally, the granulation tissue secretes inflammatory cytokines, which further increases sensitivity to pain sensations.

Physiologic Variants

Disc thickness generally increases from rostral to caudal, except for a nadir at T3-T4. The thickness of the discs relative to the size of the vertebral bodies is highest in the cervical and lumbar regions. This reflects the increased range of motion found in those regions.

In the cervical and lumbar regions, the intervertebral discs are thicker anteriorly. This creates the secondary curvature of the spine – the cervical and lumbar lordoses.

Clinical Significance

There are several terms to describe disc pathologies.

In disc bulges, the circumference of the disc extends beyond the vertebral bodies. A disc bulge may be circumferential, involving the entirety of the disc circumference, or an asymmetric bulge, which only affects one portion of the disc.[7][8][9]

A disc herniation involves the NP. Disc herniation is significant in that it may compress an adjacent spinal nerve. A herniated disc impinges upon the nerve associated with the inferior vertebrae (e.g., L4/L5 herniation affects the L5 nerve root). The most common site of disc herniation is at L5-S1, which may be due to the thinning of the posterior longitudinal ligament towards its caudal end. There are three subtypes of herniations:

- Disc protrusion is characterized by the width of the base of the protrusion is wider than the diameter of the disc material that is herniated.

- In disc extrusion, the AF is damaged, allowing the NP to herniate beyond the normal bounds of the disc. In this case, the herniated material produces a mushroom-like dome that is wider than the neck connecting it to the body of the NP. The herniation may extend superior or inferiorly relative to the disc level.

- In disc sequestration, the herniated material breaks off from the body of the NP.

Disc desiccation is common in aging. It is brought about by the death of the cells that produce and maintain the ECM, including proteoglycans, such as aggrecan. The NP shrinks as the gelatinous form is replaced with fibrotic tissue, reducing its functionality and leaving the AF to support additional weight from its normal state. This increased stress leads the AF to compensate by increasing in size. The resulting flattened disc reduces mobility and may impinge on spinal nerves leading to pain and weakness. It is thought to be due to proteoglycan breakdown, which reduces the water-retaining properties of the NP.

Significant research has been put into means of replacing/re-growing the intervertebral discs. The various methods include replacing discs with synthetic materials, stem cell therapy, and gene therapy.

Other Issues

There is no intervertebral disc between C1 and C2, which is unique in the spine.

Two major ligaments support the intervertebral discs. The anterior longitudinal ligament is a broad band that covers the anterolateral surface of the spine from the foramen magnum in the skull to the sacrum. This ligament assists the spine in preventing hyperextension and prevents intervertebral disc herniation in the anterolateral direction. The posterior longitudinal ligament covers the posterior aspect of the vertebral bodies, within the vertebral canal, and serves mainly to prevent a posterior herniation of the intervertebral discs, and is responsible for most herniations being in the postero-lateral direction.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

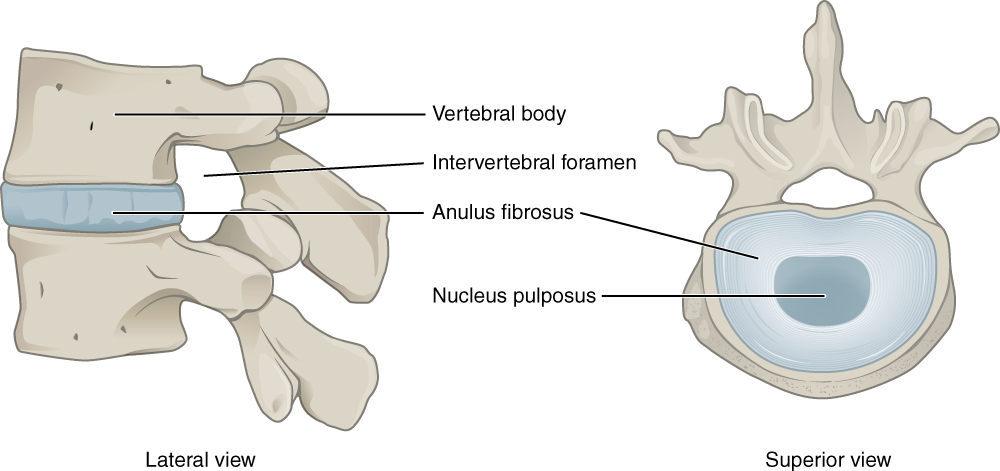

Intervertebral Disk. This lateral view shows the disc between two vertebrae. The superior view shows the annulus fibrosis at the outer layer and the nucleus pulposus in the inner layer.

Illustration from Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions Web site. http://cnx.org/content/col11496/1.6/, Jun 19, 2013. This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

References

Berg EJ, Ashurst JV. Anatomy, Back, Cauda Equina. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020623]

Huang YC, Hu Y, Li Z, Luk KDK. Biomaterials for intervertebral disc regeneration: Current status and looming challenges. Journal of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. 2018 Nov:12(11):2188-2202. doi: 10.1002/term.2750. Epub 2018 Sep 6 [PubMed PMID: 30095863]

van Uden S, Silva-Correia J, Oliveira JM, Reis RL. Current strategies for treatment of intervertebral disc degeneration: substitution and regeneration possibilities. Biomaterials research. 2017:21():22. doi: 10.1186/s40824-017-0106-6. Epub 2017 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 29085662]

Guerrero J, Häckel S, Croft AS, Hoppe S, Albers CE, Gantenbein B. The nucleus pulposus microenvironment in the intervertebral disc: the fountain of youth? European cells & materials. 2021 Jun 15:41():707-738. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v041a46. Epub 2021 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 34128534]

Williams S, Alkhatib B, Serra R. Development of the axial skeleton and intervertebral disc. Current topics in developmental biology. 2019:133():49-90. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2018.11.018. Epub 2019 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 30902259]

Fournier DE, Kiser PK, Shoemaker JK, Battié MC, Séguin CA. Vascularization of the human intervertebral disc: A scoping review. JOR spine. 2020 Dec:3(4):e1123. doi: 10.1002/jsp2.1123. Epub 2020 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 33392458]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWaxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Black AC, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Cervical Vertebrae. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083805]

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Thoracic Vertebrae. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083651]

Waxenbaum JA, Reddy V, Williams C, Futterman B. Anatomy, Back, Lumbar Vertebrae. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083618]

Abi-Hanna D, Kerferd J, Phan K, Rao P, Mobbs R. Lumbar Disk Arthroplasty for Degenerative Disk Disease: Literature Review. World neurosurgery. 2018 Jan:109():188-196. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2017.09.153. Epub 2017 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 28987839]