Introduction

The purpose of this article is to give an introduction of the gastrointestinal system, provide an outline of basic embryology, summarize the embryological events that take place with the gastrointestinal tract, and finally provide specific tests that can be utilized to detect GI anomalies.

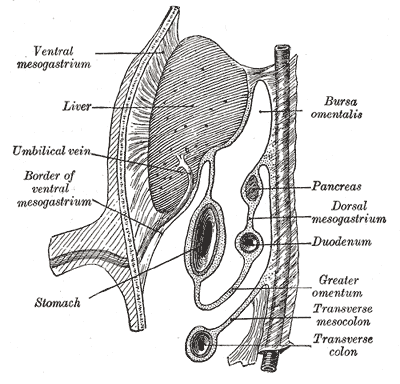

The gastrointestinal (GI) system involves three germinal layers: mesoderm, endoderm, ectoderm.

- Mesoderm gives rise to the connective tissue, including the wall of the gut tube and the smooth muscle.

- Endoderm is the source of the epithelial lining of the gastrointestinal tract, liver, gallbladder, pancreas.

- Ectoderm further separates into the surface ectoderm, neural tube, and neural crest. The surface ectoderm is the precursor to the epidermis, lens of eyes, nails, hair. The neural tube differentiates into the brain and spinal cord. The neural crest is the source of the peripheral nervous system, including the neurons of the GI tract (also called the enteric nervous system).[1]

The gastrointestinal system has the divisions: the foregut, midgut, and hindgut. The foregut (or anterior gut) is from the oral cavity to the initial part of the duodenum. The midgut is from the mid-duodenum to the initial two-thirds of the transverse colon. The hindgut is from the later one-third transverse colon to the upper portion of the anus. The three sections of the GI tract have different blood supplies; the foregut receives vascular supply by the celiac artery, the superior mesentery artery supplies the midgut, and the hindgut gets its supply from the inferior mesentery artery.[2]

Development

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Development

During the first three weeks of fetal development, implantation of the blastocyst occurs. This occurs around the same time as secretion of hCG, which is the hormone detected for pregnancy tests. During the second week, the bilaminar disc forms, which includes the epiblast and hypoblast. During the third week of development, gastrulation occurs; the epiblast cells invaginate, replace the hypoblast, and proliferate into the middle layer, while the primitive streak forms the ectoderm. This process of gastrulation leads to the development of the three germ layers: ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm. These layers form different parts of each system, as discussed above.

During week four, the heart begins to beat and can be detected by ultrasound by week six. Also during week four, limb buds begin to form. By week eight fetal movements begin and by week ten, the genitalia forms.

The changes that occur during embryology take place simultaneously. Organogenesis (development of the organs) occurs from weeks three to eight. Avoiding teratogens especially during these weeks is crucial. The following are the embryological changes that occur specifically with the gastrointestinal tract.

-

Week 3: the digestive tube starts differentiating. Gastrulation occurs. Initially, the prime gut tube forms as a hollow cylinder of endodermal cells surrounded by mesoderm. The endoderm sheet elongates and folds ventrally at the anterior and posterior ends, meeting near the yolk sac to form a closed tube.[1]

-

Week 4: resorption of the buccopharyngeal membrane occurs, which closes the cranial end of the digestive tube.[2]

-

Week 6-10: midgut herniates throughout the umbilical ring, where it develops almost entirely outside the peritoneal cavity, then rotates back around in week ten.

-

Week 7: obliteration of the omphalomesenteric duct (vitelline duct), which connects the midgut lumen to the yolk sac

-

Week 9: Opening of the distal cloacal membrane.[2] Villus formation begins[3]

-

Week 11: distinctive longitudinal and circular muscle layers are present through the intestines

-

Week 12: crypt development begins.

-

Week 14: muscularis mucosae develops

- Week 24: fetal intestinal absorption function develops

-

Week 32: fetal intestinal absorption reaches adult level.[4]

Gastrointestinal development also includes the development of the enteric nervous system. The enteric nervous system (ENS) includes two ganglion neuron networks: the location of the myenteric (Auerbach) plexus is between the inner circular and the outer longitudinal muscle layers, the submucosal (Meissner) plexus is situated adjacent to the mucosal layer. These cells derive from the neural crest cells. The enteric nervous system is developed through many complex mechanisms, such as axon guidance and synaptogenesis, leading to the proliferation, migration, and differentiation of ENS precursors. These plexuses work with smooth muscle cells and mucosal villi to control the absorption and secretion of the GI system. The smooth muscle cells are derived from mesoderm and differentiate in a rostral to caudal wave.[3]

Cellular

Different epithelial cell types are present by 12 weeks and are resembling adult cells of the intestine by 22 weeks.

Enteric nervous system development, as well as that of other cells in the gut, is regulated by different factors, including the sonic hedgehog and Indian hedgehog, bone morphogenetic protein, Wnt signaling, and platelet-derived growth factor. The hedgehog signaling is vital for early left and right patterning, along with villi formation. The bone morphogenetic protein is essential for dorsal-ventral patterning. Wnt signaling is involved in anterior-posterior signaling, villi formation, and epithelial stem cell proliferation in the intestines. PDGF plays a significant role in smooth muscle differentiation.

These signaling pathways are essential for the cell systems to develop and integrate for GI function.[3]

Testing

- Fetal kidneys produce amniotic fluid, and it is swallowed through the mouth by the fetus. A defect in the kidneys can lead to a low quantity of amniotic fluid (oligohydramnios), and defective swallowing of the amniotic fluid can lead to excess amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios)

- The diagnosis of a GI obstruction is possible in the late second to early third trimester.

- Amniotic fluid can be assessed to help check fetal health. There are many ways to assess the quantity of amniotic fluid. An ultrasound can provide accurate data about the amount of amniotic fluid.

- Clinical palpation to measure the single deepest vertical pocket

- Amniotic fluid index (AFI) using the four-quadrant technique; this is the most popular and reliable method.

- AFI <5 cm is oligohydramnios

- AFI >25 cm is polyhydramnios

- AFI between 8-25 is considered normal.[5]

- Fetal MRI can be used to complement the findings of an ultrasound.[6]

Pathophysiology

There can be many defects that take place during embryogenesis that affect the GI tract.

- Atresia is the absence or abnormal growing of an opening or a passage.

- Ventral wall defects due to a failure of closure

- Gastroschisis: contents protrude through abdominal folds and not covered by amnion or peritoneum.

- Omphalocele: abdominal contents fail to return to the abdomen and are sealed by peritoneum

- GI atresia is a failure of a portion of the GI tract to develop. The bowel will be distended at the level at the level of obstruction, while distal segments will be less distended.[2]

- Esophageal atresia has an association with tracheoesophageal fistula which allows air to enter the stomach

- Duodenal atresia occurs due to failed recanalization. It has an association with a “double bubble” sign as well as with Down syndrome.

- Jejunal and ileal atresia occurs when there is disruption of the mesenteric vessels leading to necrosis

- Hirschsprung’s disease

- Occurs with altered peristalsis

- Lack of neural crest-derived- ganglion neurons in a part of the colon due to abnormal migration, differentiation, or proliferation of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.[7]

- Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis

- Acquired narrowing of the pylorus

- The presentation includes projectile, nonbilious vomiting with a palpable olive mass in the abdomen

- May include a peristaltic wave after being fed.[8]

- Meconium ileus

- Is associated with cystic fibrosis

- Defined as the lack of passage of stool at birth due to obstruction of meconium.[9]

- Malrotation of the gut

- Improper positioning of the bowel leading to the formation of fibrous bands

- Volvulus

- Twisting of bowel around its mesentery

- Vitelline fistula

Clinical Significance

Many different pathophysiological processes can occur during embryogenesis of the GI tract. Many of these can are correctable by surgery and do not cause fetal demise in utero. A few of these embryological defects have associations with other diseases, such as cystic fibrosis and Down syndrome. Therefore, babies with meconium ileus and duodenal atresia require close monitoring and further evaluation for cystic fibrosis and Down syndrome, respectively.

It is vital during pregnancy to get routine ultrasounds to assess for polyhydramnios to suspect any GI anomalies. If a GI anomaly is suspected, it is important to monitor closely for any future surgeries needed for the baby.[10]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Williams ML, Bhatia SK. Engineering the extracellular matrix for clinical applications: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. Biotechnology journal. 2014 Mar:9(3):337-47. doi: 10.1002/biot.201300120. Epub 2014 Jan 3 [PubMed PMID: 24390851]

Huisman TA, Kellenberger CJ. MR imaging characteristics of the normal fetal gastrointestinal tract and abdomen. European journal of radiology. 2008 Jan:65(1):170-81 [PubMed PMID: 17374467]

Hao MM, Foong JP, Bornstein JC, Li ZL, Vanden Berghe P, Boesmans W. Enteric nervous system assembly: Functional integration within the developing gut. Developmental biology. 2016 Sep 15:417(2):168-81. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2016.05.030. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27235816]

Moriyama IS, [Development of fetal organs and adaptation to extrauterine life]. Nihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai zasshi. 1986 Aug [PubMed PMID: 3746039]

Hebbar S, Rai L, Adiga P, Guruvare S. Reference ranges of amniotic fluid index in late third trimester of pregnancy: what should the optimal interval between two ultrasound examinations be? Journal of pregnancy. 2015:2015():319204. doi: 10.1155/2015/319204. Epub 2015 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 25685558]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLau PE, Cruz S, Cassady CI, Mehollin-Ray AR, Ruano R, Keswani S, Lee TC, Olutoye OO, Cass DL. Prenatal diagnosis and outcome of fetal gastrointestinal obstruction. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2017 May:52(5):722-725. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.01.028. Epub 2017 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 28216077]

Das K, Mohanty S. Hirschsprung Disease - Current Diagnosis and Management. Indian journal of pediatrics. 2017 Aug:84(8):618-623. doi: 10.1007/s12098-017-2371-8. Epub 2017 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 28600660]

Peters B, Oomen MW, Bakx R, Benninga MA. Advances in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology. 2014 Jul:8(5):533-41. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2014.903799. Epub 2014 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 24716658]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSathe M, Houwen R. Meconium ileus in Cystic Fibrosis. Journal of cystic fibrosis : official journal of the European Cystic Fibrosis Society. 2017 Nov:16 Suppl 2():S32-S39. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2017.06.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28986020]

Furey EA, Bailey AA, Twickler DM. Fetal MR Imaging of Gastrointestinal Abnormalities. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2016 May-Jun:36(3):904-17. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150109. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27163598]