Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Stomach Gastroepiploic Artery

Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis: Stomach Gastroepiploic Artery

Introduction

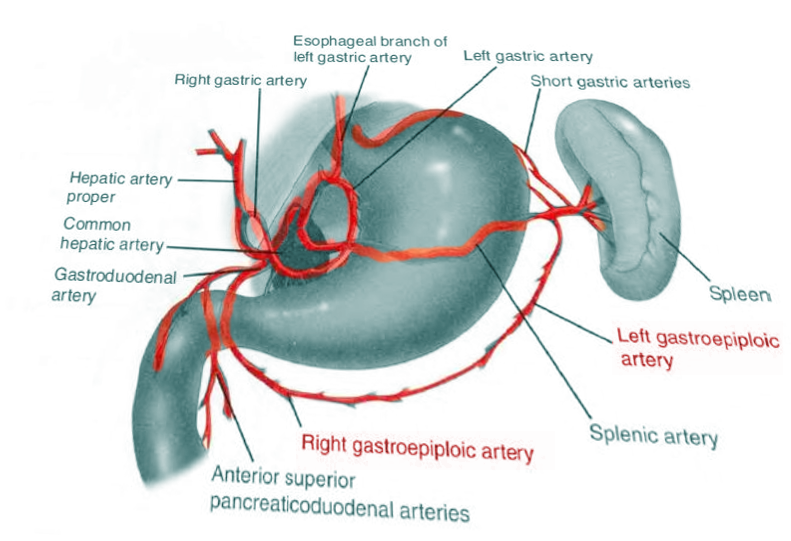

The gastroepiploic artery (GEA) comprises 2 arteries that supply the greater omentum and the stomach (see Image. Gastroepipolic Artery). The right gastroepiploic artery (RGEA) is also referred to as the right gastro-omental artery or arteria gastroepiploic dextra in older texts. The RGEA is 1 of the distal vessels branching off the gastroduodenal artery. The vessel courses along the great curvature of the stomach in a right-to-left direction. It travels between the layers of the greater omentum, giving off gastric and omental branches, and can create an anastomosis with the left gastroepiploic artery. In older texts, the left gastroepiploic artery (LGEA) is also known as the left gastro-omental artery or arteria gastroepiploic sinistra. The LGEA is usually smaller in diameter than the RGEA and commonly branches from the splenic artery near the tail of the pancreas. It courses medially along the greater curvature of the stomach towards the RGEA, giving off gastric and omental branches.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The RGEA supplies blood to the anterior and posterior antrum and lower body of the stomach. The RGEA also supplies inferior branches to the right greater omentum, which can sometimes branch and supply the final segments of the duodenum. The LGEA reaches the stomach about the midpoint of the greater curvature and supplies blood to the anterior and posterior body of the stomach. The LGEA also supplies the middle colic artery's greater omentum and anastomotic branches.[1]

Embryology

The formation of blood vessels initiates with the development of blood islands or islets of Wolff in the mesenchyme of the splanchnic mesoderm, before the yolk sac and later of the allantois. The intra-embryonic vessels originate from the blood islands in front of the protocordal disk, where a horseshoe-shaped plexiform network forms that surrounds the cephalic portion of the embryo. At the same time, 2 groups of angioblastic cells in a dorsal paramedian position form 2 parallel vessels, the dorsal aortas, which cephalically connect to the plexiform network. The vascular system's further development consists of forming ducts of greater caliber from the primitive plexiform network. The most voluminous are the right and left primitive aorta, from which the fetal arterial tree originates, which develops parallel to the cardiac tube and its subsequent evolution.

The formation of anastomoses between the intra- and extra-embryonic vessels completes the circulatory system.

The vasculature that supplies the gastrointestinal system originates from the anterior ventral segmental arteries of the primitive aorta between 2 layers of dorsal mesogastrium. The tenth segmental artery is the source of the foregut artery (celiac artery). This artery supplies blood to all foregut structures, migrates causally, and rotates in concert with the stomach during embryonic development. The celiac artery gives rise to both the hepatic and splenic arteries. The hepatic artery further branches into the gastroduodenal artery, giving rise to the RGEA. The splenic artery then gives rise to the LGEA. The RGEA and LGEA, along with other local structures, elongate with the development of the greater curvature of the stomach and lesser sac.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

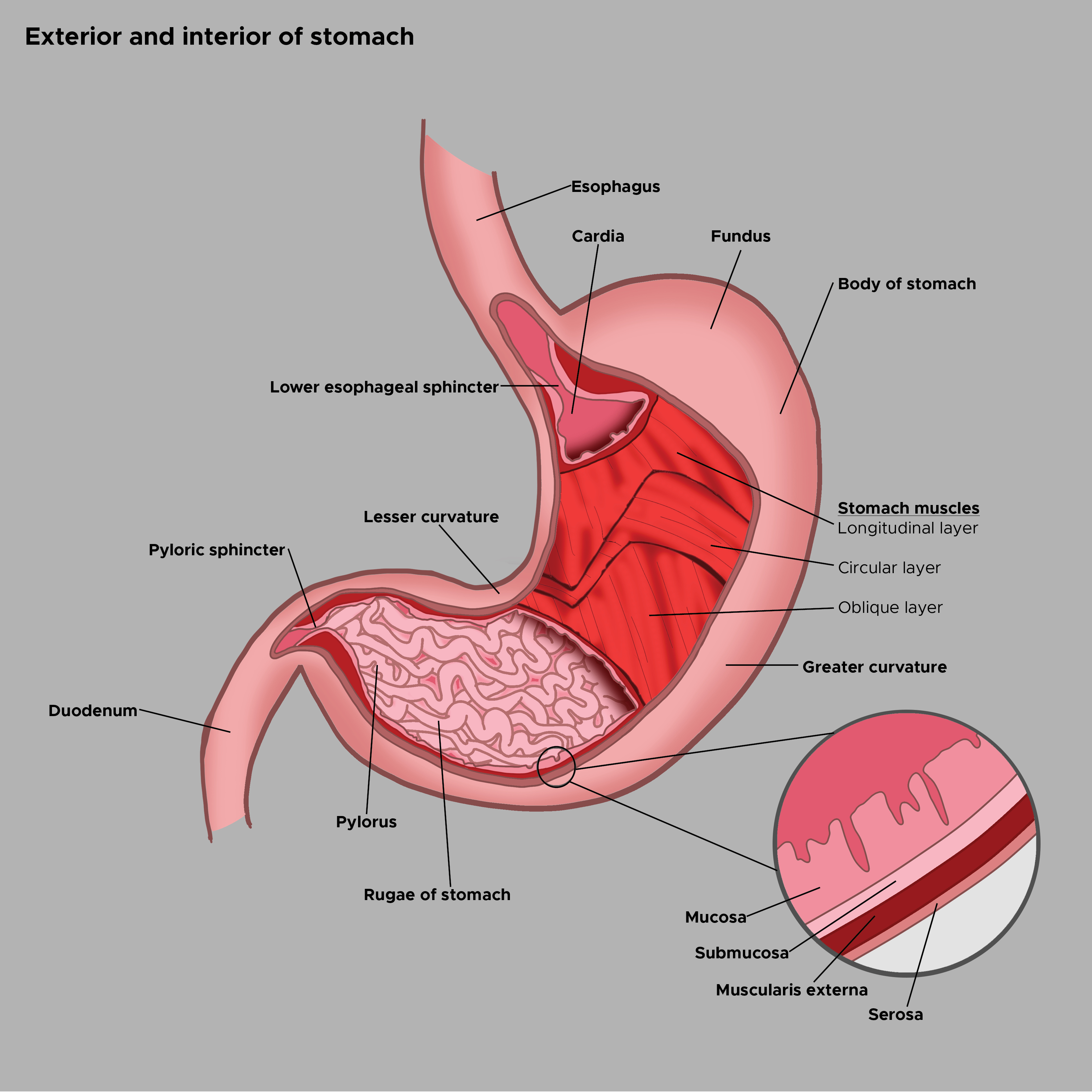

The origin of the RGEA is usually posterior to the first part of the duodenum, arising from the gastroduodenal artery. Its course varies, but often, it parallels the gastroduodenal artery distally along the pylorus, turns medially, and travels between the greater curvature of the stomach and the greater omentum (see Image. Exterior and Interior of the Stomach). After turning medially, the RGEA commonly lies about 2 centimeters below the stomach, sandwiched between layers of the gastrocolic omentum anteriorly and posteriorly. The artery gives off superior branches that supply the anterior and posterior gastric antrum and the distal body of the stomach. The RGEA also gives off inferior branches that supply the greater omentum; a few of these branches can sometimes supply the final segments of the duodenum.[1]

The LGEA originates from the splenic artery (or as a branch with the inferior splenic artery) near the pancreatic tail. The artery originates slightly medial to, and then courses toward, the gastrosplenic ligament; it runs toward the stomach, reaching the greater curvature at the level of the anterior pole of the spleen. It then turns and runs left-to-right and caudally about 2 centimeters below the stomach, letting off superior gastric and posterior omental branches.[1] The LGEA can sometimes create an anastomosis with the RGEA. Through instrumental evaluations using computed tomographic angiography, we highlight the presence of lymphocytes and lymph nodes relative to the gastroepiploic artery.

Nerves

The gastroepiploic artery is innervated by the periarterial sympathetic nerve, which allows the artery to contract, stimulating the endothelial and smooth muscle. The contraction of the artery can be slow (if stimulated by alpha2-adrenoceptors) or faster (if stimulated by alpha1-adrenoceptors). The production of nitric oxide influences the presence of arterial tone modulation.

Conversely, C-type natriuretic peptide influences vasodilation. It relaxes the arterial tone through the activation of some channels, including the large-conductance calcium-activated K+ channel and the G-protein-gated inwardly-rectifying potassium channel.

Muscles

Smooth muscle cells contain alpha-smooth-actin, which allows the vessel to contract. Other proteins that influence the vessel's mobility, such as collagen and elastin, are also present. Gamma-smooth-actin is present but in smaller quantities.

Physiologic Variants

Evidence of anastomosis between the LGEA and the RGEA ranges from about 50 to 94%. One anatomical study of 17 cadavers has shown that 94% of vessels are anastomose, with 70% being continuous (without a branching system connecting the two). Various other angiogram studies have shown a 43 to 65% anastomosis rate, with 23 to 37% continuous.[2]

The RGEA has been shown to have many different origins. The RGEA most commonly branches from the gastroduodenal artery but may branch off the superior mesenteric artery when no gastroduodenal artery develops [3]. Anatomical studies have also shown that the RGEA receives equal-sized branches from both the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries.[4]

The LGEA often arises as a common branch with the inferior splenic artery and then branches into 2 separate arteries distally in its course. The omental branches of the LGEA have been shown to create anastomoses with branches of the middle colic artery.[1]

Surgical Considerations

The stomach depends largely on the RGEA and right gastric arteries for its blood supply; therefore, surgeons need to minimize iatrogenic damage that could compromise these vessels during surgery. However, it merits noting that there is plentiful collateral blood supply to the stomach. Thus, damage to gastric vasculature creates more bleeding risk than ischemia. Gastrointestinal ischemia stemming from a compromised GEA mainly occurs at gastric walls near the anastomoses between the RGEA and LGEA on the anterior and posterior greater curvature of the stomach. The LGEA is sometimes vulnerable during surgical mobilization of the colonic splenic flexure. The early RGEA is not easily accessible surgically because of its location posterior to the duodenum and is not as vulnerable in most surgeries.[1]

Clinical Significance

The RGEA and LGEA are notable landmarks when identifying anatomy inside the abdomen. The distal vessels are usually visible both laparoscopically and during open operations. The stomach can be located cephalad to these vessels and the omentum caudad. Penetrating traumatic injury can compromise the RGEA and LGEA, causing copious bleeding. Damage of this type would require prompt surgical intervention to control hemorrhage.

GEA aneurysms

One of the rarest types of aneurysms is a visceral artery aneurysm; GEA aneurysms make up roughly 3.5% of all visceral artery aneurysms. The most frequent etiology is atherosclerotic disease. The aneurysm is typically asymptomatic; thus, diagnosis is commonly made only after rupture. If a non-ruptured lesion is incidentally found, the recommendation is to have an elective repair performed because the vessel has a high risk of complication and a likelihood of future rupture.[5]

Esophagectomy

The RGEA and LGEA both donate blood flow to the stomach and are useful in creating a gastric tube during an esophagectomy. Many physicians who perform this procedure choose to preserve the RGEA for blood supply when other vessels are ligated to mobilize the stomach. The RGEA can supply enough blood to serve as the main source of blood for a reconstructed stomach. One anatomic study measuring resins injected into the vasculature of 30 cadavers showed that the RGEA (and its branches) directly supplied 60% of the gastric tube post-esophagectomy. The LGEA and anastomotic branches supplied another 20% of the gastric tube.[6]

Cardiac Grafting/Physiology

The RGEA is an appropriate and dependable graft for coronary bypass surgery and has been shown to undergo less arteriosclerosis than other graft vessel candidates.[3] In some ways, it mirrors the internal thoracic artery's functionality for cardiac grafting. Research into the response of various neurotransmitters and their effect on the RGEA compared to the internal thoracic artery has shown that both vessels contract in response to ergonovine, serotonin, phenylephrine, and norepinephrine.[7][8] Histamine has a paradoxical effect and differs in response regarding the 2 vessels, causing contraction of the internal thoracic artery and dilatation of the RGEA.[9] Doppler mini-probe has shown an increase in RGEA blood flow following meals. This physiological response is thought to be due to the increased need for blood flow to the digestive tract following meals by histamine.[10][11]

Other Issues

LGEA may have anatomical variations. For example, 1 study reported a rare variation discovered by cadaver dissection. After its splenic origin, it could cross the pancreatic parenchyma in its posterior superficial portion; it exits posteriorly from the superior border of the pancreas to finally branch into an omental branch, into a duplicated LGEA and another branch that ends in the main trunk of the left gastroepiploic artery.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Stomach Exterior and Interior Aspects. The illustration shows the exterior landmarks for the stomach's cardia, fundus, body, lesser and greater curvatures, pylorus, and pyloric sphincter. The interior lining of the stomach comprises the mucosa, submucosa, and muscularis externa, all covered by the serosal layer. The muscularis externa is comprised of the inner oblique, middle circular, and outer longitudinal layers. The lower esophageal sphincter and stomach rugae are also shown. The esophagus and duodenum are included for reference.

Contributed by C Rowe

References

Vandamme JP, Bonte J. The blood supply of the stomach. Acta anatomica. 1988:131(2):89-96 [PubMed PMID: 3369288]

Tomioka K, Murakami M, Saito A, Ezure H, Moriyama H, Mori R, Otsuka N. Anatomical and surgical evaluation of gastroepiploic artery. Okajimas folia anatomica Japonica. 2016:92(3-4):49-52. doi: 10.2535/ofaj.92.49. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27319299]

Suma H. Gastroepiploic artery graft in coronary artery bypass grafting. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery. 2013 Jul:2(4):493-8. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.06.04. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23977628]

Liebermann-Meffert DM, Meier R, Siewert JR. Vascular anatomy of the gastric tube used for esophageal reconstruction. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1992 Dec:54(6):1110-5 [PubMed PMID: 1449294]

Faler B, Mukherjee D. Hemorrhagic shock secondary to rupture of a right gastroepiploic artery aneurysm: Case report and brief review of splanchnic artery aneurysms. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc. 2007 Spring:16(1):24-6 [PubMed PMID: 22477245]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRino Y, Yukawa N, Sato T, Yamamoto N, Tamagawa H, Hasegawa S, Oshima T, Yoshikawa T, Masuda M, Imada T. Visualization of blood supply route to the reconstructed stomach by indocyanine green fluorescence imaging during esophagectomy. BMC medical imaging. 2014 May 22:14():18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2342-14-18. Epub 2014 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 24885891]

O'Neil GS, Chester AH, Schyns CJ, Tadjkarimi S, Pepper JR, Yacoub MH. Vascular reactivity of human internal mammary and gastroepiploic arteries. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1991 Dec:52(6):1310-4 [PubMed PMID: 1755686]

Koike R, Suma H, Kondo K, Oku T, Satoh H, Fukuda S, Takeuchi A. Pharmacological response of internal mammary artery and gastroepiploic artery. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1990 Sep:50(3):384-6 [PubMed PMID: 2400258]

Suma H. The Right Gastroepiploic Artery Graft for Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: A 30-Year Experience. The Korean journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2016 Aug:49(4):225-31. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2016.49.4.225. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27525230]

Takayama T, Suma H, Wanibuchi Y, Tohda E, Matsunaka T, Yamashita S. Physiological and pharmacological responses of arterial graft flow after coronary artery bypass grafting measured with an implantable ultrasonic Doppler miniprobe. Circulation. 1992 Nov:86(5 Suppl):II217-23 [PubMed PMID: 1424003]

Toda N, Okunishi H, Okamura T. Responses to dopamine of isolated human gastroepiploic arteries. Archives internationales de pharmacodynamie et de therapie. 1989 Jan-Feb:297():86-97 [PubMed PMID: 2658894]