Introduction

Finger joint dislocation is a common hand injury. Finger dislocation can occur at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP), distal interphalangeal (DIP), or metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints. This topic discusses the epidemiology, anatomy, examination, imaging, treatment, and complications of finger dislocation.

Fingers have 3 joints: the MCP, the PIP, and the DIP. The MCP joint is between the metacarpals and proximal phalanges. The PIP joint is a hinge joint between the proximal and middle phalanges. The DIP is also a hinge joint between the middle and distal phalanges. The range of motion of these joints allows for flexion and extension, which provides grasping, pinching, and clawing or reaching functions of the fingers. The middle phalanx range of motion at the PIP joint is 105 +/- 5 degrees and accounts for the majority of the flexion of the fingertip during grasping. Flexion and extension of the digit are also possible at the metacarpophalangeal joint; however, the MCP joint can also perform adduction, abduction, and circumduction.[1]

The phalangeal joints have important stabilizers that provide necessary support during motion. Joint stabilizers are both static and dynamic. Static stabilizers consist of non-contractile tissue, including the collateral ligaments, volar plate, dorsal capsule, sagittal bands, and ulnar and radial collateral ligaments. The volar plate is an essential stabilizer as it reinforces the volar side of the joint capsule and maintains stability by preventing hyperextension of the finger joints.[2] The collateral ligaments provide stabilization against radial and ulnar deviation of the interphalangeal joints. Sagittal bands encircle the MCP joint to keep the extensor tendon centralized and to prevent bowstringing. Dynamic stabilizers include extrinsic and intrinsic tendons and muscles, and 2 important dynamic stabilizers are the central slip and lateral bands. The central slip tendon is found dorsally and provides for PIP joint extension, and the lateral bands provide DIP joint extension. Finally, digital arteries and nerves are found volar and appear on both the ulnar and radial sides of the digit.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Finger dislocations can involve the MCP, PIP, or DIP joints and may occur in the dorsal, volar, or lateral planes. Dislocations are categorized according to the position of the distal bone relative to the more proximal bone.[4] Hyperextension or high-energy axial loads at the MCP joint can result in dislocation. MCP joint dislocation infrequently occurs because of the protection against hyperextension by the volar plate and radial and ulnar deviation by the collateral ligaments (see Image. Metacarpophalangeal Joint Dorsal Dislocation). The most common MCP joint dislocation is the index finger. MCP joint dislocation of the middle finger occurs more frequently when subjected to ulnar stress during hyperextension.[2] Most common MCP joints dislocate dorsally.[4] The typical presentation of MCP joint dislocation is with the IP joint in flexion and the MCP joint in extension. A non-reducible dislocation with dimpling on the volar surface indicates volar plate interposition.[1]

PIP joint dislocations are the most common due to sports and are known as coach’s finger. See Image. Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Dorsal Dislocation. The typical presentation of PIP joint dislocation is a deformity, decreased range of motion, and pain. PIP joint dislocations can be classified into dorsal, volar, and lateral dislocations. PIP joint dislocation is most commonly dorsal; however, volar dislocation correlates with a higher rate of complications and more difficult reductions.[4][1] Dorsal dislocation results from longitudinal compression and hyperextension, commonly by a ball hitting the fingertip. Dorsal PIP joint dislocation most commonly occurs at the middle finger and is associated with volar plate, collateral ligament, and dorsal joint capsule injury. Swan neck deformity often occurs in dorsal dislocations resulting from volar plate injury. Trapping of the volar plate inside the joint may occur, causing malalignment and oblique rotation, resulting in challenging reductions. Volar dislocation of the PIP joint can occur with and without rotation of the intermediate phalanx. Volar dislocation is infrequent and can be associated with injury to the central slip of the extensor tendon. Untreated rupture of the central slip after PIP joint dislocation is associated with pseudo-boutonniere (PIP flexion contracture). Pseudo-boutonniere is a chronic PIP joint flexion with the absence of DIP extension [5]

Lateral PIP dislocation can also occur and involves disruption of the collateral ligaments. The patient presents with joint instability and the widening of the joint on radiographs. Finally, rotary volar dislocations may occur when the phalanx displaces and rotates around 1 collateral ligament, allowing the proximal phalanx to wedge between the lateral band and extensor tendon. The classic lateral radiographic finding has the colloquial description of the “Chinese finger trap.”[1] DIP joint dislocations typically present with deformity at the fingertip. Dorsal, lateral, and volar DIP joint dislocations are all possible (see Image. Distal Interphalangeal Joint Dorsal Dislocation). Dorsal DIP joint dislocations occur most frequently and are associated with fractures and skin injuries. They are not always associated with flexor tendon avulsions but may have an interposed volar plate causing a non-reducible dislocation. Volar DIP joint dislocations are similar to dorsal PIP joint dislocations in that both are associated with extensor tendon injuries. The lateral DIP joint is more likely to have post-reduction instability than volar or dorsal dislocations. Isolated DIP joint dislocation without related injuries such as soft tissue or fractures is rare and is commonly managed with closed reduction and splinting in the emergency departments.[6][1]

Epidemiology

From 2004 to 2008, approximately 166000 finger dislocations received treatment in US Emergency Departments. Most dislocations occur between 15 and 19 years of age and affect African Americans more than other racial groups. They occur most commonly in basketball and football players.[7]

History and Physical

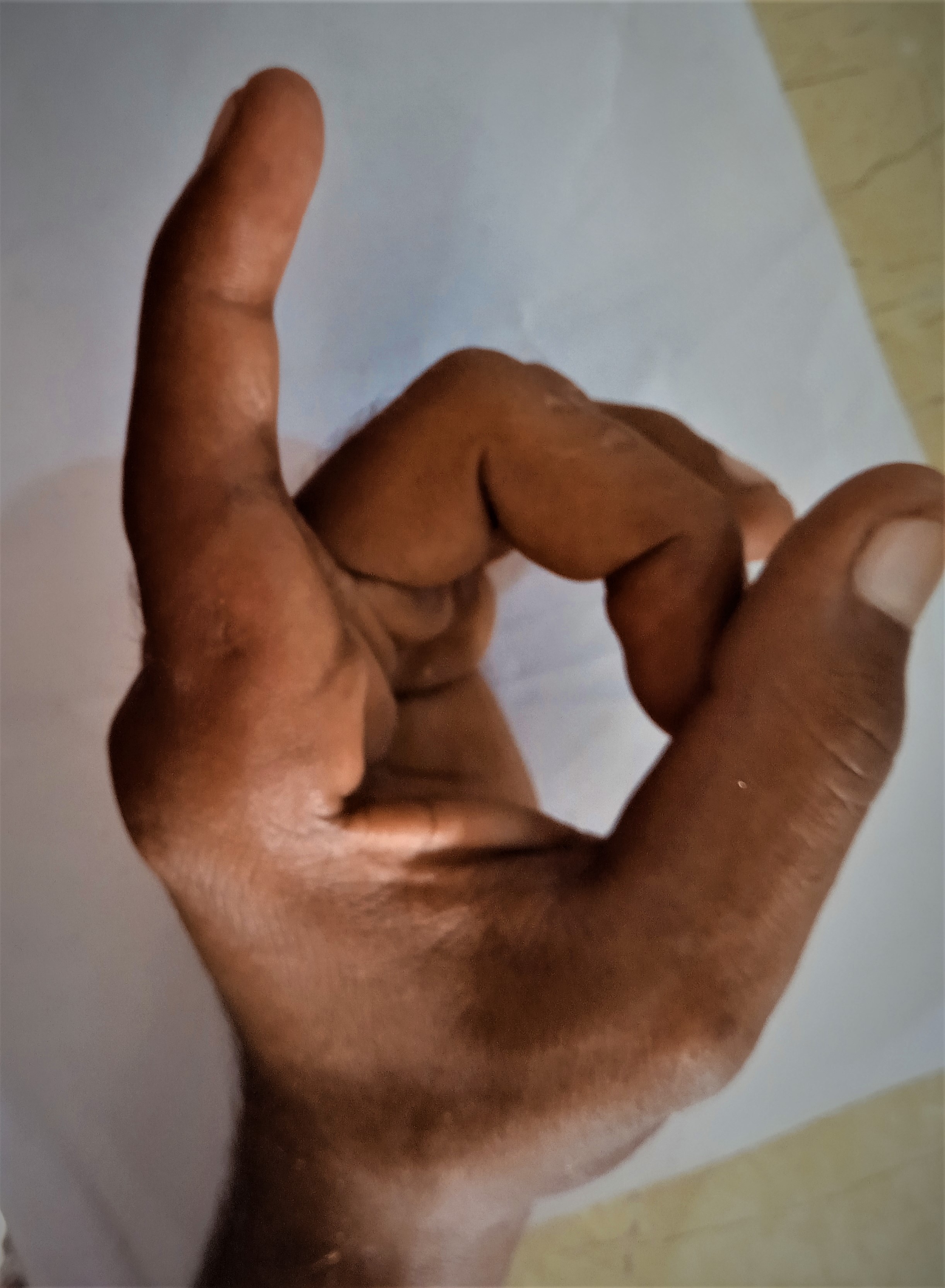

Examiners must perform a complete history, which includes risk factors such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, mechanism of injury, handedness, previous finger injuries, occupation, and hobbies. Ample lighting should be used to examine the hand for skin integrity, ecchymosis, swelling, or bony deformity. If skin integrity becomes compromised due to laceration or abrasion, the examiner's goal is to evaluate in a bloodless field if possible. Examiners may use finger tourniquets or, in a patient with adequate circulation, an anesthetic with epinephrine can be used.[8] Finger examination must be through its complete active and passive range of motion.[9] A thorough neurovascular exam is imperative in the evaluation of the injured hand. To identify potential digital nerve injury, the injured digit should be compared to the same digit on the unaffected hand for light-touch, pinprick, and 2-point discrimination. On the opposite hand, the digital artery can be evaluated by comparison to an unaffected digit using a capillary refill. If the examiner identifies a deformity, the examiner must also determine if there is any rotation or angulation. Hyperextension of the finger joint should be performed to assess the competency of the volar plate. Lateral stress of the finger joint is performed to test the collateral ligaments. The Elson test is performed to evaluate the integrity of the central slip. To assess for rotation or angulation, the patient is asked to make a fist if possible, and all the fingertips should point toward the scaphoid. Overlapping or "scissoring" indicates a rotational component to the injury. Rotated or angulated fractures are also identifiable by comparison of the digital pulp and nails with the unaffected hand. Palpation can be used to determine the location of maximal tenderness.[4]

Evaluation

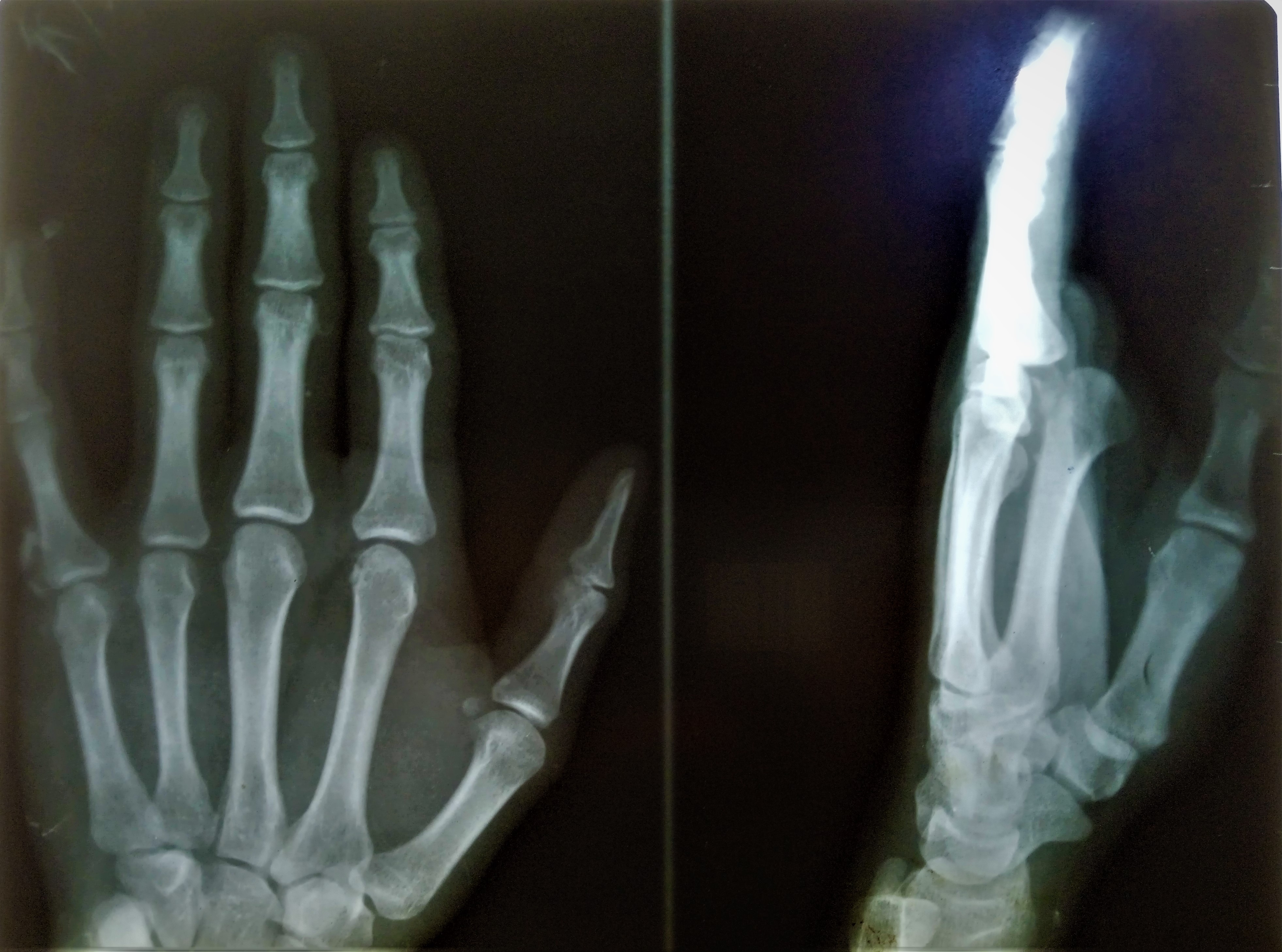

The standard of care for evaluating injuries to the hand is plain film imaging (see Image. Radiograph of a Left Proximal Interphalangeal Dislocation). True lateral, anterior-posterior, and oblique views are necessary for each affected digit. The films must demonstrate a clear view of the affected digit. Unaffected fingers must not obscure the view of the affected digit. Examiners should remember that rotational deformities are most commonly diagnosed on physical exams rather than plain films.[4] In addition to plain films, ultrasound (US) continues to be an area of research identifying fractures and tendon ruptures.[10]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of MCP, PIP, and DIP joint dislocation may be operative or nonoperative depending on the ease of reduction, post-reduction stability, or involvement of the volar plate or other stabilizing structures. Before any reduction, a digital nerve block using lidocaine, bupivacaine, or tetracaine injected at the dorsal base of the dislocated finger provides immediate anesthesia.[11](A1)

Metacarpophalangeal Joint Dislocation Management

Nonoperative Management

Nonoperative management of MCP joint dislocations consists of closed reduction and splinting. The clinician can achieve the closed reduction by extension and axial compression on the proximal phalanx by relocating pressure over the phalangeal base to glide it into position. This approach is different than the traction technique used in PIP joint dislocation. Multiple reduction attempts should be avoided as the inability to reduce may indicate volar plate interposition requiring open reduction. Multiple attempts at MCP joint dislocation reduction have the potential complication of displacing the volar plate between articular surfaces, lumbricals, or flexor tendons. The finger should have to splint with the wrist extended 30 degrees and the MCP joint in 30 to 60 degrees of slight flexion to prevent terminal extension for about 3 to 6 weeks, followed by an additional 2 weeks of buddy taping.

Operative Management

Operative intervention is indicated for nonreducible MCP joint dislocation, as volar plate involvement is highly likely in these cases. Open reduction of MCP joint dislocation can be performed using either a dorsal or volar approach; however, the dorsal approach is preferable as it carries a lower risk of neurovascular injury. After surgery, the wrist is splinted in 30 degrees of extension with the MCP joint in slight flexion for 2 weeks to prevent terminal extension. The recommendation is that the PIP and DIP joints not be immobilized. Recovery to preinjury motion typically occurs between 4 to 6 weeks.[12]

Volar Approach for MCP Joint Dislocation

To prevent neurovascular damage, a volar Bruner incision is made over the MCP joint between the proximal and distal volar creases while the patient is under general anesthesia. The flexor tendons are on the ulnar side, whereas the neurovascular bundle is on the radial side. The volar plate's proximal connection on the metacarpal usually gets ruptured. By releasing the A1 pulley, the tension created by the muscle-tendon constriction around the metacarpal neck is released. Superficial transverse ligament, natatory ligament, and palmar fascia are incised. The joint can be manually reduced following a vertical incision in the volar plate. The volar plate's free slips are wrapped around the metacarpal's head, and stitches are secured using absorbable sutures. A dorsal block splint is applied following skin closure. After healing, active flexion activities are promoted. The splint is removed at 3 weeks, and active extension exercises are introduced.[13]

Dorsal Approach for MCP Joint Dislocation

Over the metacarpophalangeal joint, a dorsally curved incision is made either on the ulnar aspect or the radial side. Usually, a dorsoradial incision is made for the 1st & 2nd MCP joints; however, a dorsoulnar incision is preferred for the 4th and 5th MCP joints (see Image. First Metacarpophalangeal Joint Dorsal Dislocation). The skin flaps are raised, protecting sensory nerve branches and longitudinal veins. The extensor aponeurosis is incised longitudinally along the extensor digitorum tendon. Capsulotomy of the MCP joint is done longitudinally. An elevator is used to shift the intervening volar plate ventrally, which reduces the MCP joint. Clinical testing is done on reduction and stability. Following surgery, the MCP joint is immobilized for 2 weeks at 30 degrees of flexion, and then extension block splinting is done for 4 weeks.[14] (B3)

The benefits of the dorsal open reduction method include good volar plate visibility, prevention of digital neurovascular injury, and correct reduction of the metacarpal head osteochondral fracture. However, this procedure could require longitudinally division of the volar plate and extensor apparatus, impairing MCP stability.[15] The volar open reduction method has benefits such as clear visibility of the MCP joint, which aids in the surgical removal and realignment of the volar plate. In a volar approach to the MCP joint, the radial digital nerve and the neurovascular structures ventral to the lumbrical muscles are at risk.[16] It has been demonstrated that the dorsal approach is safe for the open reduction of complex MCP dislocation. In this procedure, the deep transverse ligament need not be divided. Although the volar technique enables anatomical reduction of the volar plate and MCP joint, there is a chance that it might harm the volar neurovascular bundle; therefore, it requires strong clinical experience. Both provide a stable MCP joint with appropriate functional outcomes.[17](B3)

Proximal Interphalangeal Joint Dislocation Management

Nonoperative Management

PIP joint dislocations are also manageable with operative and nonoperative options. Still, unlike MCP joint dislocations, practitioners must determine if the PIP joint dislocation is dorsal, volar, lateral, or rotary, as the treatment may differ. For closed reduction of dorsal PIP joint dislocation, the practitioner should apply slight extension and longitudinal traction and, on the other hand, apply pressure to the dorsal aspect of the proximal phalanx to relocate the displaced digit. After reduction, the examiner should evaluate the joint for instability in all planes and obtain radiographs. The normal contour of the dorsal aspect of the PIP joint on lateral plain film is "C" shaped. If, after reduction, this contour takes on a "V" shape, it may indicate persistent dorsal subluxation, which can lead to severe stiffness.[2] PIP joint dislocation is often stable after reduction and is treated by dorsal splinting at 30 degrees of flexion. Volar PIP dislocations are the least common, but reducing the volar PIP joint dislocation is generally successful. The reduction occurs by applying mild traction with the PIP and MCP joints in slight flexion. After reducing the volar dislocation, an extension splint is applied for 6 weeks.

Unlike volar PIP joint dislocation, lateral dislocations are more likely to require operative intervention. Closed reduction requires relaxation of the extensor tendon and lateral bands by wrist extension and MCP flexion, respectively. Then, the middle phalanx is gently rotated back into position. If the lateral PIP joint dislocation reduction provides a full range of motion without subluxation, then the joint is not grossly unstable. Splinting and reassessment in 2 or 3 weeks are recommended in these cases. Splinting remains the mainstay of emergency treatment post-reduction. A recent randomized control trial compared buddy taping versus aluminum orthosis treatment of Eaton grades I and II hyperextension-type injuries and found no difference in strength, pain, or function at 3 weeks. However, the buddy tape did show an earlier range of motion and decreased edema.[18](A1)

Operative Management

All unstable dislocations require referral for orthopedic evaluation and possible open repair. Indications for operative intervention regarding PIP joint dislocation include joint instability, significant ligament, soft tissue, tendon injury, or dislocations that are not reducible.

Dorsal Approach For PIP Joint Dislocation

For volar PIP dislocations, the dorsal approach is indicated.[19] Midline longitudinal incision, curvilinear incision, and lazy S incision are used for the dorsal approach of the PIP joint. The convexity of the incision is designed such that the scar affects neither the ulnar nor radial borders of the little finger. Full-thickness skin flaps are elevated, preserving the sensory nerve branches and the longitudinal superficial veins, while the transverse vein may be ligated. After exposing the extensor aponeurosis, there are 3 ways to approach the PIP joint capsule: in between central & lateral slip, splitting of central slip (Swanson approach)[20], and flap elevation of central slip (Chamay approach).[21] A capsulotomy is done transversely, preserving the central slip and extensor tendons.

Volar Approach For PIP Joint Dislocation

A Bruner or zigzag incision is made between the flexor crease and the PIP joint. After raising thick skin flaps, flexor pulleys are released (C1, A3, C2). The A2 and A4 pulleys should not be incised as they would lead to flexor tendons' bowstringing. The flexor tendons are retracted, and the joint capsule is incised. The volar plate is mobilized, and the layered closer is done.[22](B2)

Lateral Approach For PIP Joint Dislocation

A mid-axial incision is used over the PIP joint, and a plane is made between the dorsal extensor tendon & volar digital neurovascular bundle. The transverse retinacular and collateral ligaments are incised to expose the PIP joint, which is later repaired after reduction.[23]

Distal Interphalangeal Joint Dislocation Management

NNonoperativeManagement

DIP joint dislocation management is less complex than PIP joint dislocation. The 3 types of DIP joint dislocation are dorsal, volar, and lateral. The most common type of DIP joint dislocation is dorsal. Dorsal DIP joint dislocation is reduced with longitudinal traction, relocating dorsal pressure on the distal phalanx with DIP joint in flexion. Often, the reduction occurs easily in the emergency room setting, followed by splinting of DIP in 10 to 20-degree flexion for 2 to 3 weeks.[6] If persistent DIP joint instability, such as those found more commonly in lateral dislocation, is treated with 4 to 6 weeks of K-wire fixation after concentric reduction.

Operative Management

Irreversible dislocation is typically due to volar plate interposition and requires surgical intervention. A zigzag or mid-axial incision is centered over the distal interphalangeal joint. The entrapped flexor digitorum profundus and volar plate are mobilized to reduce the DIP joint. After confirming concentric reduction and stability, range of motion exercises are initiated immediately after operative reduction.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for finger dislocations are as follows:

- Fracture-dislocation

- Collateral ligament injuries - normally referred to as finger “sprains.”

- Tendon avulsion

Staging

Depending upon the direction of dislocation

- Dorsal dislocation

- Volar dislocation

- Lateral dislocation

- Rotatory dislocation

- Fracture dislocation[24]

Depending upon volar plate interposition

- Simple

- Complex[13]

Prognosis

The prognosis for finger dislocations are as follows:

- MCP joint dislocations are highly likely to require operative intervention, and recovery to preinjury motion takes approximately 4 to 6 weeks.[12]

- Most PIP joint dislocations are stable after reduction except lateral PIP joint dislocation, as they often require surgical intervention.

- Isolated DIP joint dislocation is rare, and like PIP joint dislocation, lateral DIP joint dislocation more often requires surgical intervention.[6]

Complications

Complications for finger dislocations include:

- Chronic stiffness is common after DIP dislocation treatment.

- Overtreatment, such as prolonged splinting and multiple attempts at reduction of volar PIP joint dislocations, increases the likelihood of volar plate scarring and flexion contractures.

- Chronic pain

- Reduced mobility of MCP, PIP, and DIP joints.

- Missing or delayed volar plate injuries are associated with boutonniere deformity, swan neck deformity, laxity, and contractures.

- Swan neck deformity, PIP flexion contracture, and mallet finger deformity may also occur if the dislocations of the finger are chronically unrecognized.

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After the reduction of simple dislocations, an early range of motion is permitted, but a dorsal extension block splint restricts extension past neutral. After the reduction of complex dislocations, 2 weeks of MCP joint immobilization is done in 30 degrees of flexion with a removable dorsal extension block splint. Gentle mobilization and range of motion exercises are started intermittently. Following removing the splint, the following activities are started: fist-making, finger lifting, passive stretching, full range of motion, and eccentric exercises to strengthen the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. The distal interphalangeal joint needs to be mobilized immediately to ensure that the lateral bands glide smoothly.[18][25]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Physical therapy, occupational therapy, and return to play or work training are often necessary. The orthopedic or hand surgeon should give education on how to care for the injury until recovery is complete.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Finger dislocation evaluation, management, and treatment are complex. Orthopedic and hand surgeon consultation and close follow-up are critical to decreasing the likelihood of the many complications associated with this injury. Since finger dislocation most commonly occurs in athletes, the discussion for return to play is also complex and requires communication between the orthopedic specialist, hand surgeon, and player. An orthopedic nurse can assist in the care, answer patient questions, assist during any procedural interventions, serve as a bridge between therapists and the clinician, and monitor progress toward healing. Physical or occupational therapy may be in order, with the therapist providing and charting updates so the entire team knows the current patient status. Specialists and nurses collaborating as an interprofessional team can enhance outcomes in diagnosing and managing finger dislocations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Prucz RB, Friedrich JB. Finger joint injuries. Clinics in sports medicine. 2015 Jan:34(1):99-116. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.09.002. Epub 2014 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 25455398]

Sundaram N, Bosley J, Stacy GS. Conventional radiographic evaluation of athletic injuries to the hand. Radiologic clinics of North America. 2013 Mar:51(2):239-55. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.09.015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23472589]

Minami A, An KN, Cooney WP 3rd, Linscheid RL, Chao EY. Ligament stability of the metacarpophalangeal joint: a biomechanical study. The Journal of hand surgery. 1985 Mar:10(2):255-60 [PubMed PMID: 3980940]

Hile D, Hile L. The emergent evaluation and treatment of hand injuries. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2015 May:33(2):397-408. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2014.12.009. Epub 2015 Feb 26 [PubMed PMID: 25892728]

Lo I, Richards RS. Combined central slip and volar plate injuries at the PIP joint. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1995 Jun:20(3):390-1 [PubMed PMID: 7561419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang QC, Johnson BA. Fingertip injuries. American family physician. 2001 May 15:63(10):1961-6 [PubMed PMID: 11388710]

Golan E, Kang KK, Culbertson M, Choueka J. The Epidemiology of Finger Dislocations Presenting for Emergency Care Within the United States. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2016 Jun:11(2):192-6. doi: 10.1177/1558944715627232. Epub 2016 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 27390562]

Ilicki J. Safety of Epinephrine in Digital Nerve Blocks: A Literature Review. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2015 Nov:49(5):799-809. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.05.038. Epub 2015 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 26254284]

Gaston RG, Chadderdon C. Phalangeal fractures: displaced/nondisplaced. Hand clinics. 2012 Aug:28(3):395-401, x. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2012.05.032. Epub 2012 Jun 26 [PubMed PMID: 22883890]

Tayal VS, Antoniazzi J, Pariyadath M, Norton HJ. Prospective use of ultrasound imaging to detect bony hand injuries in adults. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2007 Sep:26(9):1143-8 [PubMed PMID: 17715307]

Yin ZG, Zhang JB, Kan SL, Wang P. A comparison of traditional digital blocks and single subcutaneous palmar injection blocks at the base of the finger and a meta-analysis of the digital block trials. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 2006 Oct:31(5):547-55 [PubMed PMID: 16930788]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCalfee RP, Sommerkamp TG. Fracture-dislocation about the finger joints. The Journal of hand surgery. 2009 Jul-Aug:34(6):1140-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.04.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19643295]

An MT, Kelley JP, Fahrenkopf MP, Kelpin JP, Adams NS, Do V. Complex Metacarpophalangeal Dislocation. Eplasty. 2020:20():ic3 [PubMed PMID: 32499843]

Mahajan NP, Patil TC, Sangma S. Management of Complex Kaplan's dislocation by Open Dorsal Approach - A Case Report. Journal of orthopaedic case reports. 2021 Nov:11(11):84-87. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2021.v11.i11.2526. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35415108]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKAPLAN EB. Dorsal dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1957 Oct:39-A(5):1081-6 [PubMed PMID: 13475407]

Dinh P, Franklin A, Hutchinson B, Schnall SB, Fassola I. Metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2009 May:17(5):318-24 [PubMed PMID: 19411643]

Barry K, McGee H, Curtin J. Complex dislocation of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint of the index finger: a comparison of the surgical approaches. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1988 Nov:13(4):466-8 [PubMed PMID: 3249153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaschos NK, Abuhemoud K, Gantsos A, Mitsionis GI, Georgoulis AD. Management of proximal interphalangeal joint hyperextension injuries: a randomized controlled trial. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Mar:39(3):449-54. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.11.038. Epub 2014 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 24503231]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCheah AE, Yao J. Surgical Approaches to the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint. The Journal of hand surgery. 2016 Feb:41(2):294-305. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.11.013. Epub 2015 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 26708513]

Swanson AB, Maupin BK, Gajjar NV, Swanson GD. Flexible implant arthroplasty in the proximal interphalangeal joint of the hand. The Journal of hand surgery. 1985 Nov:10(6 Pt 1):796-805 [PubMed PMID: 4078262]

Chamay A. A distally based dorsal and triangular tendinous flap for direct access to the proximal interphalangeal joint. Annales de chirurgie de la main : organe officiel des societes de chirurgie de la main. 1988:7(2):179-83 [PubMed PMID: 3190311]

Lin HH, Wyrick JD, Stern PJ. Proximal interphalangeal joint silicone replacement arthroplasty: clinical results using an anterior approach. The Journal of hand surgery. 1995 Jan:20(1):123-32 [PubMed PMID: 7722251]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGreen SM, Posner MA, Garay A. Silicone rubber arthroplasty of the proximal interphalangeal joint: dorsal and lateral approaches. Seminars in arthroplasty. 1991 Apr:2(2):130-8 [PubMed PMID: 10149611]

Hubbard LF. Metacarpophalangeal dislocations. Hand clinics. 1988 Feb:4(1):39-44 [PubMed PMID: 3277978]

DeDeugd CM, Rizzo M. Surgical Exposure of the Proximal Interphalangeal Joint. Hand clinics. 2018 May:34(2):127-138. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2017.12.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29625633]