Introduction

Felty syndrome, also known as Chauffard-Still-Felty disease, is an uncommon extra-articular manifestation of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis (RA) characterized by RA, neutropenia (ANC<1500 mm3), and splenomegaly. HLA-DR4 has been noted to be present in >90% of Felty syndrome cases.[1] The American physician Augustus Felty described Felty syndrome in 1924 at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He described 5 unusual cases with common features of chronic arthritis of about 4 years duration, splenomegaly, and striking leukopenia. The term was first used by Hanrahan and Miller in 1932 when they described the beneficial effect of splenectomy in a patient with features similar to the 5 cases reported by Felty. While Felty syndrome characteristically demonstrates chronic arthritis, splenomegaly, and neutropenia; completion of the triad is not necessary for the diagnosis. Neutropenia, however, is a hallmark feature of the disease and cannot be absent.[2] This syndrome poses diagnostic challenges due to its infrequency and variable clinical presentation. Felty syndrome not only warrants astute clinical observation and diagnostic acumen but also demands a multidisciplinary approach to comprehensive management, incorporating the skills and expertise of physicians, advanced care practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There is strong evidence suggesting the presence of the HLA-DRB1 allele shared epitope as a risk factor for anticyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody development. Anti-CCP antibodies are highly specific for RA, with a specificity of about 96%.[3] Rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-CCP positivity are associated with an increased risk of the development of extra-articular RA (ExRA).[4] HLA-DRB1 includes DRB1*01 and DRB1*04. HLADRB1*04 homozygosity correlates with the development of more severe and erosive RA. A large multicenter study evaluating the impact of HLA-DRB1 genes in patients with ExRA confirmed a strong association between HLA-DRB1*0401 and Felty syndrome. In the same study, there was a lack of association between ExRA and HLA-DQB1 alleles and DRB1-DQB1 haplotypes favoring the specific role of HLA-DRB1 genes.[5]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of Felty syndrome in patients with RA is reported to be approximately 1% to 3%.[6] With the evolution of RA pharmacotherapy, including increased use of methotrexate (MTX) and biologics, the risk of Felty syndrome seems to be declining, and true prevalence is very low.[7] Felty syndrome usually develops about 16.1 years after RA presentation, with increased risk in patients with a positive family history of RA. There is also a stronger association of RA with HLA DR4 in patients with Felty syndrome[2] The disease follows the same pattern as RA and affects females 3 times more than males, is diagnosed in middle age, and affects the White population more compared to non-White populations.[8][9]

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of Felty syndrome is not clear, and it may be multifactorial. It is thought to involve both humoral and cellular immune mechanisms, contributing to neutrophil survival and proliferation defects resulting in neutropenia.[10] Neutropenia can be explained by inadequate production due to infiltration of bone marrow by cytotoxic lymphocytes and increased sequestration due to splenomegaly supported by the improvement of neutropenia after splenectomy.

A case-control study done for the presence of antibodies against granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) showed that 73% of patients with neutropenia due to Felty syndrome had IgG Anti-G-CSF, which was associated with an exaggerated serum level of G-CSF and a low neutrophil count. This finding suggests that a high level of G-CSF and hyposensitivity of myeloid cells to G-CSF might be responsible for the development of neutropenia in patients with Felty syndrome.[11]

Another study concluded that autoantibodies present in Felty syndrome bind to deaminated histones and neutrophil extracellular chromatin traps (NETs), leading to neutrophil sequestration and supporting the role of peripheral destruction of neutrophils in the pathophysiology of Felty syndrome.[12]

Some have suggested that chronic large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia and Felty syndrome may have a common pathologic link because of similar clinical presentation and common genetic etiology of HLA-DR4.[13] About a third of Felty syndrome patients have a clonal LGL (CD3+/CD8+) population.[14] Neutropenia in LGL leukemia has been attributed to increased secretion of circulating Fas ligand, which induces neutrophil apoptosis. Patients with LGL leukemia also often have other autoimmune diseases like RA as well as elevated levels of Fas ligand, suggesting a similar pathogenic mechanism.[15][16] About 20% of T-cell LGL leukemia (T-LGLL) patients will have RA.[17][18] The clinical overlap of T-LGLL and Felty syndrome has led to the belief that they are 2 entities on a spectrum of a common disease.[19]

History and Physical

Described as a manifestation of severe RA, Felty syndrome usually occurs in patients with severe, long-standing, erosive, and seropositive arthritis. However, the diagnosis of Felty syndrome can precede arthritis symptoms.[20][21] Although articular involvement at the onset of Felty syndromecan be quiet or active, most patients have radiographic evidence of erosive disease. Synovial effusions may be present in about 75% of patients.[22]

Patients usually present with an infection because Felty syndrome is otherwise asymptomatic.[23] The most common types of infections are dermatological and respiratory.[14] Many patients have other extra-articular manifestations. These have been reported as rheumatoid nodules (74%), hepatomegaly (68%), lymphadenopathy (42%), Sjogren syndrome (48%), pulmonary fibrosis (50%), pleuritis (22%), peripheral neuropathy (14%), and leg ulcers (16%).[24] Systemic symptoms, including fever and weight loss, may also be present.[25] Although splenomegaly is present in most cases, the involvement of the spleen is not necessary for diagnosis. The spleen is usually palpable on clinical examination. Some patients can also have idiopathic non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, which can lead to variceal bleeding.

Evaluation

Complete Blood Count

Complete blood count (CBC) with differential shows an absolute neutrophil count of <2000/µL, a hallmark feature required for the diagnosis of Felty syndrome, accounting for an increased risk of bacterial infections. Diagnosis of Felty syndrome can sometimes be made earlier if the patient’s blood counts are under surveillance for another reason, such as medication toxicity monitoring. There is no correlation between splenic enlargement and the degree of neutropenia.[26] Anemia and thrombocytopenia may be present in patients with splenic enlargement. Anemia of chronic inflammation is present in almost all patients. Felty syndrome has a greater association with autoimmune hemolytic anemia (+ Coombs) than RA.[14]

Serology

Laboratory findings of RA, like positive rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-CCP, are almost always present in Felty syndrome. Antinuclear antibodies, anti-histone antibodies, and HLA-DR4 can also be present. Anti-histone antibodies are present in 83% of Felty syndrome patients; the existence of anti-histone antibodies in a patient with RA is felt to be diagnostic of Felty syndrome.[14]

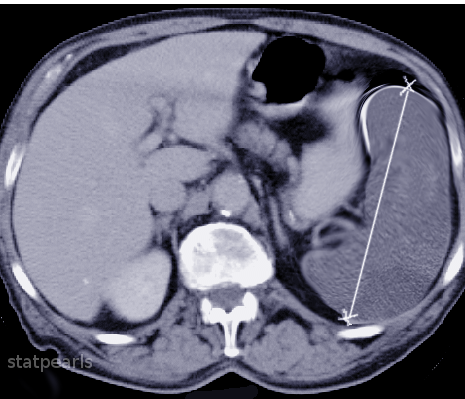

Imaging

Plain radiographs of small peripheral joints may show severe joint destruction.[27] Imaging of the spleen with ultrasound or radionuclide scan can be done to detect splenomegaly (see Image. CT Splenomegaly).

Bone Marrow Biopsy

Bone marrow biopsy shows myeloid hyperplasia in most cases with increased granulopoiesis and relative excess of immature forms described as “maturation arrest.”[25] Bone marrow biopsy helps rule out LGL leukemia; a hypoplastic marrow should raise suspicion for other pathology. Immunophenotyping of the marrow can also help diagnose LGL leukemia, denoting either T-cell (CD3+/CD8+/CD57+) or natural killer cell (CD3-/CD56+) subsets.[14]

Histology

Splenic histology in autopsies and postsplenectomy cases has shown nonspecific findings such as congestion of venous sinusoids, reticular cell hyperplasia, and germinal cell hyperplasia.

Treatment / Management

Treatment for Felty syndrome focuses on controlling the underlying RA and treating the neutropenia to prevent infections.

The goal is to achieve a granulocyte count of >2000/µL. Neutropenia without evidence of infection is not an indication for treatment; however, the presence of neutropenia in patients with RA can help in adjusting disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) therapy. Improvement of the neutrophil count with the treatment of RA indicates a component of Felty syndrome. Patients with neutropenia should undergo a thorough examination to look for signs of infection. The presence of systemic symptoms should prompt treatment. Care of neutropenic patients involves good dental and oral hygiene as well as scheduled age-appropriate immunizations. The clinician should initiate appropriate treatment of infections with broad-spectrum antibiotics, and neutropenic precautions are necessary. An infectious disease specialist consult can be helpful.

No randomized control studies are available to guide the treatment of Felty syndrome, and most of the data directing treatment are from observational studies. Low-dose oral MTX with folic acid (thwarts the anti-folate toxicity of MTX manifested in the liver, marrow, and gastrointestinal tract) is considered a first-line treatment.[1] This treatment has demonstrated benefits in improving the neutrophil count and helps prevent the recurrence of infection. Studies have shown that a dose of <7.5 mg/week results in prompt improvement of the neutrophil count within 4 to 6 weeks. Because the effect of MTX is dose-dependent, with noticeable change seen after 4 to 8 weeks, an adequate trial with a maximum tolerated dose should be considered before deeming patients unresponsive.[28][29][30](B2)

Other DMARDs have been reported to be beneficial in some reports. A case report described a patient with RA who developed Felty syndrome while on MTX therapy and then severe cutaneous allergy to etanercept, but subsequently, significant improvement in neutropenia with leflunomide.[31] Parenteral gold therapy was previously used in Felty syndrome but is outdated now due to the extensive adverse side effect profile.[32] Cyclosporine has shown a response in a few reports but is not generally an option because of the availability of other medications with a better side effect profile.[33][34] Amongst the biologic agents, rituximab, a monoclonal antibody against CD20 antigen, has been shown to provide sustained improvement in neutropenia without major adverse effects.[35][36] It can be considered in patients who fail to respond to an adequate trial of nonbiologic DMARD therapy. Limited reports on anti-tumor necrosis factor agents like infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept have not shown any benefit in neutrophil response.[36](B3)

Initially, glucocorticoids can be used in patients with Felty syndrome to improve neutrophil count rapidly. Because of the immunosuppressive effect, however, long-term use is generally not advised, and use should be avoided in patients with an active infection.[37] G-CSF is usually used in patients with absolute neutrophil count (ANC) of <1000/µL with severe and recurrent infections who fail to respond to DMARDs and rituximab adequately. In a systemic review, all patients with Felty syndrome receiving G-CSF significantly increased ANC within 1 week of treatment. In most patients, discontinuing G-CSF resulted in the decline of ANC; however, it stabilized above a pretreatment level over time. There was also an improvement in infectious complications. During an active infection, short-term treatment with the goal of an ANC >1000/µL can be beneficial. There will be an additional stimulatory effect on neutrophil function as well. Although long-term G-CSF therapy has a risk of worsening the underlying autoimmune condition, its use is a consideration in patients with severe recurrent infections with consistent ANC <1000/µL despite immunosuppressive therapy.[38](B3)

Hanrahan and Miller first performed splenectomy on a patient with Felty syndrome, a 50-year-old woman, who had marked improvement in neutropenia and arthritis over 5 months of follow-up. Subsequently, splenectomy was the main treatment option for patients with Felty syndrome.[39][26] With the development of DMARDs and other biological agents, the surgical approach now has limited indications. It is reserved for patients with significant recurrent infections with neutropenia and those who failed to respond to all medical therapies, including DMARDs, biologic agents, and G-CSF. Other rare indications of splenectomy are severe anemia requiring multiple transfusions and severe hemorrhage due to thrombocytopenia, which is unresponsive to conventional treatment.[40] Neutropenia recurs postoperatively in a quarter of cases. G-CSF has no role in this disorder beyond the transitory improvement in neutropenia when necessary. Patients with RA or Felty syndrome can have anti-GCSF antibodies that can further compound treatment challenges.[3](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The most important differential to consider in patients with RA and neutropenia is LGL leukemia. Also termed "pseudo-Felty syndrome," it can present as neutropenia with or without splenomegaly. Most patients with LGL leukemia have an associated autoimmune condition, particularly RA; therefore, it can be challenging to distinguish Felty syndrome from LGL leukemia. Immunophenotyping showing cytotoxic T lymphocytes with CD 2, 3, 8, 16, and 57 surface marker positivity, together with bone marrow biopsy and peripheral smear showing increased LGL cells, can help in differentiating the 2 diseases. Many consider these conditions part of the same disease continuum rather than separate entities. The involvement of a hematologist to rule out hematological malignancy as the cause of neutropenia is important.[41][42]

Other causes of neutropenia and splenomegaly should be evaluated and ruled out. Medications are an important cause to consider. MTX can cause bone marrow suppression and neutropenia in patients with RA. Similarly, TNF inhibitors can cause neutropenia. Worsening of neutropenia after temporary cessation of these agents provides a clue to the diagnosis of Felty syndrome.[43] Viral infections like Epstein-Barr virus and HIV can present with neutropenia and splenomegaly. If suspected, serological tests can help rule out these conditions. Other autoimmune conditions, such as lupus, which can have similar features as an extra-articular RA, can usually be distinguished through clinical features and serological tests.

Prognosis

The severity and extra-articular manifestations of RA have been decreasing gradually since MTX and biological treatments became available for the treatment of RA.[7] The incorporation of G-CSF in the treatment of chronic neutropenia has resulted in a decrease in the need for splenectomy.[44] One study conducted before the advent of MTX reported a 5-year mortality of 36% in patients with Felty syndrome, infections being the most common cause of death.[45] Recent data regarding the prognosis of Felty syndrome is lacking. However, the availability of advanced treatment options has significantly improved the prognosis for Felty syndrome.

Complications

The most important complication of Felty syndrome is severe or recurrent infections, particularly of the respiratory tract and skin, because of neutropenia. Other complications like anemia due to splenic sequestration and hemorrhage due to severe thrombocytopenia can also occur. Variceal bleeding due to portal hypertension is possible. Treatment modalities like splenectomy for refractory neutropenia can increase the risk of infections after surgery and have been fatal in a few cases. G-CSF carries a small risk of exacerbation of underlying autoimmune disorders.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although it is a rare disease, Felty syndrome should be on the differential diagnosis of any patients who present with RA and neutropenia because the consequence of any treatment delay is potentially fatal. The clinician should be mindful that neutropenia may become masked in patients with acute infection.

No specific treatment exists for patients with Felty syndrome. Although many options are available for treatment, randomized trials are lacking because of the rarity of the disease. The basis for treatment recommendations is only a few observational studies. This diagnosis, therefore, poses a therapeutic challenge in an acute setting, especially in resource-limited situations and in patients with refractory neutropenia. In nonacute settings, all patients with asymptomatic neutropenia should be advised about good oral and dental hygiene and closely monitored with adjustments in their anti-rheumatic medications to improve the neutrophil count, which can help prevent infections.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Felty syndrome is a rare disease. Therefore, a high degree of suspicion is required to make the diagnosis early and minimize its complications. Instituting an interprofessional team can help in the early detection and treatment of Felty syndrome. A collaborative multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimal patient-centered care.

Each healthcare professional has distinct responsibilities in Felty syndrome care. Physicians and advanced practitioners are responsible for accurate diagnosis and comprehensive treatment plans. Apart from the involvement of a rheumatologist, a hematologist's input is valuable to rule out hematological malignancies as the cause of neutropenia. An infectious disease specialist should be involved earlier in the care to decrease the risk of infections.

The primary care nurse can help physicians and advanced care practitioners diagnose patients with RA by obtaining a detailed interval history for possible recurrent infections, gastrointestinal bleeding, and splenic pain. Nurses can also assist the team in monitoring treatment, verifying patient compliance, and helping assess treatment effectiveness.

The pharmacist can assist clinicians in monitoring the hematologic parameters of the patient with RA, with or without therapy, to help in the early detection of the disease and for the alteration of therapy when needed. The pharmacist should also assist the medical team by providing patient education on the different drugs used to treat Felty syndrome, their benefits, and their adverse effects. Pharmacists must verify dosing (particularly with MTX), check for drug interactions in the patient's medication regimen, and inform the clinician should they encounter any concerns.

Open communication between team members is vital to improving outcomes. Clinicians must engage in clear and timely communication to share patient information, treatment plans, and updates. Regular interdisciplinary meetings can facilitate seamless care coordination, allowing each team member to contribute their expertise to optimize patient care.

Healthcare professionals must work collaboratively to ensure continuity of care, efficient transitions between healthcare settings, and timely follow-ups. Advanced practitioners, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must also stay abreast of the latest diagnostic techniques and treatment modalities for patients with Felty syndrome. Coordinated efforts enhance patient safety, reduce errors, advance care, and improve overall team performance.

Media

References

Gupta A, Abrahimi A, Patel A. Felty syndrome: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2021 May 27:15(1):273. doi: 10.1186/s13256-021-02802-9. Epub 2021 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 34039422]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCampion G, Maddison PJ, Goulding N, James I, Ahern MJ, Watt I, Sansom D. The Felty syndrome: a case-matched study of clinical manifestations and outcome, serologic features, and immunogenetic associations. Medicine. 1990 Mar:69(2):69-80 [PubMed PMID: 1969604]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAslam F, Cheema RS, Feinstein M, Chang-Miller A. Neutropaenia and splenomegaly without arthritis: think rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ case reports. 2018 Jul 11:2018():. pii: bcr-2018-225359. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-225359. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30002215]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan der Helm-van Mil AH, Verpoort KN, Breedveld FC, Huizinga TW, Toes RE, de Vries RR. The HLA-DRB1 shared epitope alleles are primarily a risk factor for anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies and are not an independent risk factor for development of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2006 Apr:54(4):1117-21 [PubMed PMID: 16572446]

Turesson C, Schaid DJ, Weyand CM, Jacobsson LT, Goronzy JJ, Petersson IF, Sturfelt G, Nyhäll-Wåhlin BM, Truedsson L, Dechant SA, Matteson EL. The impact of HLA-DRB1 genes on extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis research & therapy. 2005:7(6):R1386-93 [PubMed PMID: 16277691]

Sibley JT, Haga M, Visram DA, Mitchell DM. The clinical course of Felty's syndrome compared to matched controls. The Journal of rheumatology. 1991 Aug:18(8):1163-7 [PubMed PMID: 1941816]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBartels CM, Bell CL, Shinki K, Rosenthal A, Bridges AJ. Changing trends in serious extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis among United State veterans over 20 years. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2010 Sep:49(9):1670-5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq135. Epub 2010 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 20463190]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTermini TE, Biundo JJ Jr, Ziff M. The rarity of Felty's syndrome in blacks. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1979 Sep:22(9):999-1005 [PubMed PMID: 475875]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLewis RB. Felty's syndrome in blacks. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1980 Mar:23(3):377-8 [PubMed PMID: 7362694]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBurks EJ, Loughran TP Jr. Pathogenesis of neutropenia in large granular lymphocyte leukemia and Felty syndrome. Blood reviews. 2006 Sep:20(5):245-66 [PubMed PMID: 16530306]

Hellmich B, Csernok E, Schatz H, Gross WL, Schnabel A. Autoantibodies against granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in Felty's syndrome and neutropenic systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2002 Sep:46(9):2384-91 [PubMed PMID: 12355486]

Dwivedi N, Upadhyay J, Neeli I, Khan S, Pattanaik D, Myers L, Kirou KA, Hellmich B, Knuckley B, Thompson PR, Crow MK, Mikuls TR, Csernok E, Radic M. Felty's syndrome autoantibodies bind to deiminated histones and neutrophil extracellular chromatin traps. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2012 Apr:64(4):982-92. doi: 10.1002/art.33432. Epub 2011 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 22034172]

Liu X, Loughran TP Jr. The spectrum of large granular lymphocyte leukemia and Felty's syndrome. Current opinion in hematology. 2011 Jul:18(4):254-9. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e32834760fb. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21546829]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOwlia MB, Newman K, Akhtari M. Felty's Syndrome, Insights and Updates. The open rheumatology journal. 2014:8():129-36. doi: 10.2174/1874312901408010129. Epub 2014 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 25614773]

Liu JH, Wei S, Lamy T, Epling-Burnette PK, Starkebaum G, Djeu JY, Loughran TP. Chronic neutropenia mediated by fas ligand. Blood. 2000 May 15:95(10):3219-22 [PubMed PMID: 10807792]

Nozawa K, Kayagaki N, Tokano Y, Yagita H, Okumura K, Hasimoto H. Soluble Fas (APO-1, CD95) and soluble Fas ligand in rheumatic diseases. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997 Jun:40(6):1126-9 [PubMed PMID: 9182923]

Prasad S, Mushfiq Farooqui I, AlZoubi L, Arami S. T-cell Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia and Felty Syndrome in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Case Report. Cureus. 2023 Jul:15(7):e41780. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41780. Epub 2023 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 37575786]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCouette N, Jarjour W, Brammer JE, Simon Meara A. Pathogenesis and Treatment of T-Large Granular Lymphocytic Leukemia (T-LGLL) in the Setting of Rheumatic Disease. Frontiers in oncology. 2022:12():854499. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.854499. Epub 2022 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 35747794]

Gazitt T, Loughran TP Jr. Chronic neutropenia in LGL leukemia and rheumatoid arthritis. Hematology. American Society of Hematology. Education Program. 2017 Dec 8:2017(1):181-186. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.181. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29222254]

Armstrong RD, Fernandes L, Gibson T, Kauffmann EA. Felty's syndrome presenting without arthritis. British medical journal (Clinical research ed.). 1983 Nov 26:287(6405):1620 [PubMed PMID: 6416525]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUchida S, Kawai K, Tsutsui Y, Yamazaki M. Felty syndrome in a patient with undiagnosed rheumatoid arthritis presenting with multiple cutaneous abscesses. The Journal of dermatology. 2022 Jun:49(6):e208-e209. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16332. Epub 2022 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 35187709]

Pararath Gopalakrishnan V, Tirupur Ponnusamy J, Panginikkod S. Felty Syndrome. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2023 Oct 3:():. pii: hcad222. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcad222. Epub 2023 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 37788124]

Hoshina Y, Teaupa S, Chang D. Infective Endocarditis-Like Presentation of Felty Syndrome: A Case Report. Cureus. 2021 Dec:13(12):e20713. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20713. Epub 2021 Dec 26 [PubMed PMID: 34966628]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNonaka K, Watanabe S, Sano C, Ohta R. Treating Exudative Pleurisy Accompanied by Felty Syndrome in an Older Patient With Advanced Rheumatoid Arthritis. Cureus. 2023 Apr:15(4):e37270. doi: 10.7759/cureus.37270. Epub 2023 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 37168154]

Sienknecht CW, Urowitz MB, Pruzanski W, Stein HB. Felty's syndrome. Clinical and serological analysis of 34 cases. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1977 Dec:36(6):500-7 [PubMed PMID: 596944]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBarnes CG, Turnbull AL, Vernon-Roberts B. Felty's syndrome. A clinical and pathological survey of 21 patients and their response to treatment. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1971 Jul:30(4):359-74 [PubMed PMID: 4104268]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMorikawa S, Miyashita Y, Nasu M, Shibazaki S, Usuda S, Tsunoda K, Nakagawa T. Severe alveolar bone resorption in Felty syndrome: a case report. Journal of medical case reports. 2022 Dec 16:16(1):463. doi: 10.1186/s13256-022-03703-1. Epub 2022 Dec 16 [PubMed PMID: 36522676]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFiechtner JJ, Miller DR, Starkebaum G. Reversal of neutropenia with methotrexate treatment in patients with Felty's syndrome. Correlation of response with neutrophil-reactive IgG. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1989 Feb:32(2):194-201 [PubMed PMID: 2920054]

Wassenberg S, Herborn G, Rau R. Methotrexate treatment in Felty's syndrome. British journal of rheumatology. 1998 Aug:37(8):908-11 [PubMed PMID: 9734684]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceIsasi C, López-Martín JA, Angeles Trujillo M, Andreu JL, Palacio S, Mulero J. Felty's syndrome: response to low dose oral methotrexate. The Journal of rheumatology. 1989 Jul:16(7):983-5 [PubMed PMID: 2504919]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTalip F, Walker N, Khan W, Zimmermann B. Treatment of Felty's syndrome with leflunomide. The Journal of rheumatology. 2001 Apr:28(4):868-70 [PubMed PMID: 11327265]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDillon AM, Luthra HS, Conn DL, Ferguson RH. Parenteral gold therapy in the Felty syndrome. Experience with 20 patients. Medicine. 1986 Mar:65(2):107-12 [PubMed PMID: 3951357]

Canvin JM, Dalal BI, Baragar F, Johnston JB. Cyclosporine for the treatment of granulocytopenia in Felty's syndrome. American journal of hematology. 1991 Mar:36(3):219-20 [PubMed PMID: 1996561]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYazıcı A, Uçar A, Mehtap Ö, Gönüllü EÖ, Tamer A. Presentation of three cases followed up with a diagnosis of Felty syndrome. European journal of rheumatology. 2014 Sep:1(3):120-122 [PubMed PMID: 27708892]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChandra PA, Margulis Y, Schiff C. Rituximab is useful in the treatment of Felty's syndrome. American journal of therapeutics. 2008 Jul-Aug:15(4):321-2. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e318164bf32. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18645332]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNarváez J, Domingo-Domenech E, Gómez-Vaquero C, López-Vives L, Estrada P, Aparicio M, Martín-Esteve I, Nolla JM. Biological agents in the management of Felty's syndrome: a systematic review. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2012 Apr:41(5):658-68. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.08.008. Epub 2011 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 22119104]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJob-Deslandre C, Menkès CJ. Treatment of Felty's syndrome with auranofin and methylprednisolone. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1989 Sep:32(9):1188-9 [PubMed PMID: 2775326]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHellmich B, Schnabel A, Gross WL. Treatment of severe neutropenia due to Felty's syndrome or systemic lupus erythematosus with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 1999 Oct:29(2):82-99 [PubMed PMID: 10553980]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLaszlo J, Jones R, Silberman HR, Banks PM. Splenectomy for Felty's syndrome. Clinicopathological study of 27 patients. Archives of internal medicine. 1978 Apr:138(4):597-602 [PubMed PMID: 637640]

Coon WW. Felty's syndrome: when is splenectomy indicated? American journal of surgery. 1985 Feb:149(2):272-5 [PubMed PMID: 3970327]

Savola P, Bhattacharya D, Huuhtanen J. The spectrum of somatic mutations in large granular lymphocyte leukemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and Felty's syndrome. Seminars in hematology. 2022 Jul:59(3):123-130. doi: 10.1053/j.seminhematol.2022.07.004. Epub 2022 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 36115688]

Moosic KB, Ananth K, Andrade F, Feith DJ, Darrah E, Loughran TP Jr. Intersection Between Large Granular Lymphocyte Leukemia and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Frontiers in oncology. 2022:12():869205. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.869205. Epub 2022 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 35646651]

Hamsho S, Alannouf I, Ashour AA. Rapidly Progressive Felty Syndrome After Sudden Discontinuation of Methotrexate: A Case Report and Review of Literature. International medical case reports journal. 2022:15():473-477. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S365004. Epub 2022 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 36091198]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWard MM. Decreases in rates of hospitalizations for manifestations of severe rheumatoid arthritis, 1983-2001. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004 Apr:50(4):1122-31 [PubMed PMID: 15077294]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThorne C, Urowitz MB. Long-term outcome in Felty's syndrome. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 1982 Oct:41(5):486-9 [PubMed PMID: 7125718]