Introduction

Esophageal perforation poses a significant interprofessional challenge to the entire therapeutic team. It can occur in three different anatomical compartments and therefore presents with diverse symptoms; most of them are highly non-specific which can significantly delay the time between perforation and final diagnosis. Despite the marked improvement in the availability of diagnostic techniques and therapeutic approaches, esophageal perforation remains a direct life-threatening condition with mortality rates reaching as high as 50%. The frequency of esophageal perforation is 3 in 100,000 in the United States, with intrathoracic perforations being most common (54%) followed by cervical esophagus perforations (27%), then intra-abdominal perforations (19%).[1][2][3][4]

Anatomy

The esophagus is a 25-cm long fibromuscular tube that connects the pharynx to the stomach. It starts in the neck at the level of C6 vertebra, extending through the mediastinum until its insertion in the diaphragm at the level T10 vertebra via a separate opening in the right crus of the diaphragm. Along its vertical course, the esophagus has three constrictions:

- The first constriction is approximately 15 cm from the upper incisor teeth, where the esophagus begins at the cricopharyngeal sphincter at the level of the sixth cervical vertebra.

- The second constriction is approximately 23 cm from the upper incisor, which is the landmark of the crossing of the aortic arch and the left main bronchus.

- The third constriction is approximately 40 cm from the upper incisor, where it pierces the diaphragm and forms the physiologic lower esophageal sphincter at the tenth thoracic vertebra.

The esophagus is divided into three portions:

- The cervical esophagus extends from the cricopharyngeus muscle to the suprasternal notch and is supplied by the inferior thyroid artery.

- The thoracic esophagus, considered the longest segment, extends from suprasternal notch to the diaphragm and is supplied by bronchial and esophageal branches of the descending thoracic aorta.

- The abdominal esophagus, the shortest division, extends from the diaphragm to the cardia of the stomach and is supplied by branches of the left phrenic and left gastric arteries.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Iatrogenic perforations are a group of perforations caused by instrumentation for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes. Diagnostic endoscopy, performed almost exclusively with flexible endoscopes, carries a low risk of perforation; however, therapeutic interventions such as pneumatic dilation, hemostasis, stent placement, foreign body extraction, cancer palliation, and endoscopic ablation techniques can dramatically increase the risk of perforation. Iatrogenic perforation is common in the hypopharynx or the distal esophagus while spontaneous rupture may occur in the posterolateral wall of the esophagus just above its diaphragmatic hiatus. Despite being rare overall, iatrogenic esophageal perforations can also be the result of invasive surgical maneuvers, with fundoplication and esophageal myotomy being the most common operations associated with the complication.[5][6][7]

- Spontaneous ruptures are the most common cause of non-iatrogenic perforations (15% of all esophageal perforations), which result from a sudden increase in intra-esophageal pressure, combined with negative intrathoracic pressure. Spontaneous rupture usually occurs in a longitudinal fashion and varies in size from 0.6 cm to 8.9 cm long, with the left side more commonly affected than the right (90%).

- Traumatic injuries of the esophagus that are secondary to penetrating or blunt forces are rare but life-threatening causes of esophageal perforations. Penetrating injuries due to gunshot wounds or stab wound are more common than blunt injuries, which can be masked by associated more severe injuries (e.g., cardiac contusion or aortic dissection).

- Ruptures secondary to a foreign body impaction are rare. Esophageal distal third impactions are the most common site for impaction predisposed by peptic stricture, achalasia or esophagitis. Middle third impactions are frequently reported to be facilitated by strictures or obstructive neoplasms. Foreign body impaction can be complicated by pressure necrosis, leading to wall ischemia in the affected segment and resulting in necrosis with subsequent perforations.

Epidemiology

Esophageal perforation occurs in 3 in 100,000 people in the United States. Of those cases, 25% are cervical; 55%, intrathoracic; and 20%, abdominal.

Pathophysiology

Because the esophagus lacks a serosal layer, it is very vulnerable to rupture and perforation. Once a perforation occurs, retained gastric contents, saliva, biliary fluid, and other secretions may enter the mediastinum and cause chemical mediastinitis with mediastinal emphysema, inflammation, and subsequently, mediastinal necrosis. Within a few hours following a full-thickness tear in the esophageal wall, polymicrobial bacterial translocation and invasion occur, which can lead to sepsis and eventually death if there is a delayed diagnosis or lack of appropriate medical and surgical care. Pleural effusion often follows esophageal perforation, which can be either a sympathetic effusion (when the pleura is still intact) or an exudative effusion (when the mediastinal pleura ruptures and contaminated gastric fluid is drawn into the pleura by the negative intrathoracic pressure).

History and Physical

The clinical manifestations of esophageal perforations depend on several factors including the etiology of the perforation, the location of the perforation (cervical, intrathoracic or intra-abdominal), the severity of contamination, injury of nearby mediastinal structures (trachea in a case of penetrating trauma in cervical esophageal perforations or the pericardium in case of spontaneous thoracic perforations), and the time elapsed from the perforation until treatment.[8][9]

- Cervical esophageal perforations can be presented with neck pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, or dysphonia. Crepitus or tenderness can be elicited on neck palpation.

- Thoracic esophageal perforations are presented with retrosternal chest pain, often preceded by retching and vomiting in patients diagnosed with Boerhaave syndrome. Patients may have crepitus on chest wall palpation caused by subcutaneous emphysema. Mediastinal crackling can be heard on auscultation in patients with mediastinal emphysema. Symptoms and signs of pleural effusion such as dyspnea, tachypnea, dullness on chest percussion, and decreased fremitus may be detected.

- Abdominal esophageal perforations are presented with epigastric pain radiating to the shoulder which might be associated with nausea or vomiting. Transmural tears, extending through the serosa is frequently complicated by peritoneal contamination and patients present with acute peritonitis.

- Fever, tachycardia, tachypnea, hypotension, and cyanosis are signs of late mediastinitis and shock and considered a poor prognostic indicator.

Evaluation

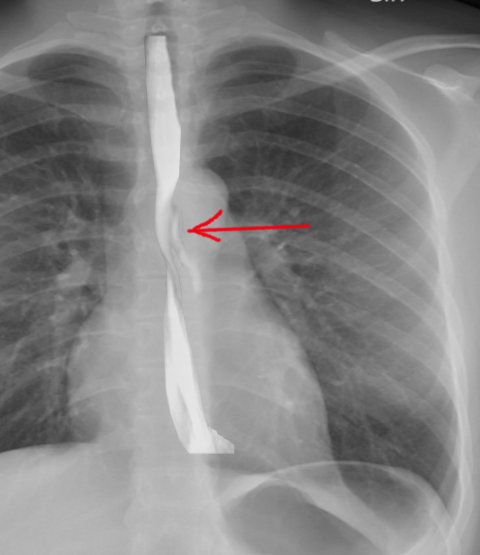

- Plain radiography is used to detect air that has escaped from the perforated esophagus. Subcutaneous emphysema in the case of cervical esophageal rupture, mediastinal air (pneumomediastinum), and widening is indicative of thoracic perforation while free air under the diaphragm is clear evidence of abdominal esophageal perforation. Other findings that may show on plain X-rays include pleural effusion, pericardial effusion, hydrothorax, hydropneumothorax, and air in soft tissues of the prevertebral space.

- Contrast esophagography is used to establish and to confirm the diagnosis of esophageal perforation. Leakage of contrast material is a sure sign to establish the diagnosis of perforation. Dye extravasation can also help determine the location and extent of the rupture. Barium contrast studies are superior to water contrast materials in terms of accuracy and specificity; however, due to the higher risk of barium-induced chemical mediastinitis, water contrast studies are preferred.

- Computed tomography (CT scan) of the chest and abdomen should be performed when esophageal perforation is suspected. It has the advantage of showing intrathoracic or intra-abdominal collections that require percutaneous or surgical drainage. CT findings may include periesophageal fluid collections (pleural effusion, ascites), esophageal thickening, and pneumomediastinum.

Treatment / Management

Patients with esophageal perforations are of high mortality risk; even with prompt medical care, mortality can reach as high as 36% to 50%. Hence, optimized initial resuscitation is critical to ensure appropriate delivery of care to the affected patients. [10][11](A1)

Initial Management

- ICU admission for all unstable patients or high-risk patients with multiple comorbidities

- Hemodynamic monitoring, volume resuscitation, and stabilization.

- NPO (Nil Per Os)

- TPN (Total Parenteral Nutrition)

- Intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and antifungals

- Intravenous proton pump inhibitors

- Percutaneous drainage of any fluid collection

- Assessment for operative versus nonoperative management

- Feeding J-tube

Standard Care of Management

- Endoscopic stent placement: Performed in selected stable patients; esophageal perforations can be covered with synthetic stents delivered via esophageal endoscopy. Failure of this intervention is mostly attributed to either stent migration, malpositioning, or inability to create an air/fluid tight seal between the stent and the margins of the esophageal defect.

- Drainage with/out debridement: Surgical drainage is performed without further operation as most of the esophageal perforations will heal if drained adequately.

Surgical Management

Operative management is required for most patients to minimize morbidity and mortality.

- Patients diagnosed early (less than 24 hours after the perforation) can be treated with debridement of all devitalized contaminated tissue followed by primary repair. In addition, the primary repair should be enhanced with the use of a vascularized pedicle flap using serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, or the diaphragm.

- Patients who present by extensive leakage of fluid, substantial tissue necrosis, or devitalization or by major fluid collections should undergo emergent surgical stenting, debridement, or drainage to restore the integrity of the esophagus.

- In rare situations, diversion procedures or resection of the esophagus with proximal esophagostomy and feeding gastrostomy/jejunostomy can be a valid option in patients with extensive contamination who are not candidates for primary repair due to friability of the surrounding tissue or pre-existing esophageal disease (inoperable malignancy).

- Postoperative healing can be enhanced by placing a feeding jejunostomy or gastrostomy tube to abstain from oral feeding for more prolonged periods of time and ensure maximum healing conditions for the esophagus, especially when substantial extraluminal leakage exists. However, this operation is optional and relies on the surgeon's preference.

- Oral feedings should be restored when the patient is stable, with a contrast esophagram study confirming the integrity of the esophagus and the absence of any leakage.

Differential Diagnosis

- Acute aortic dissection

- Acute coronary syndrome

- Acute pericarditis

- Aspiration pneumonitis and pneumonia

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Emergent management of pancreatitis

- Empyema and abscess pneumonia

- Mallory-Weiss tear

- Myocardial infarction

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary embolism

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Esophageal perforation poses a significant challenge to the entire therapeutic team. These patients may present with a variety of nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal, retrosternal chest pain, or vomiting and may also exhibit signs of sepsis and shock. An interprofessional, cooperative team is crucial to delivering optimal and appropriate care. While the general surgeon is almost always involved in managing patients with esophageal ruptures and perforations, other specialists such as a radiologist, intensivist, thoracic surgeon, and expert endoscopist should be involved in providing adequate care for these patients. Surgical residents should also have a high threshold to suspect or diagnose esophageal perforations. A radiologist has a key role in the diagnosis of esophageal ruptures and tears, especially complex or small perforations with minimal leaks.

The mortality of esophageal perforations can be as high as 50%, thus to improve outcomes, prompt consultation with an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended.

Media

References

Younes Z, Johnson DA. The spectrum of spontaneous and iatrogenic esophageal injury: perforations, Mallory-Weiss tears, and hematomas. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 1999 Dec:29(4):306-17 [PubMed PMID: 10599632]

White RK, Morris DM. Diagnosis and management of esophageal perforations. The American surgeon. 1992 Feb:58(2):112-9 [PubMed PMID: 1550302]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBadertscher P, Delko T, Oertli D, Reuthebuch O, Schurr U, Pradella M, Kühne M, Sticherling C, Osswald S. Surgical repair of an esophageal perforation after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal. 2019 May-Jun:19(3):110-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ipej.2019.01.004. Epub 2019 Jan 24 [PubMed PMID: 30685314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDudzinski DM, Mangalmurti SS, Oetgen WJ. Characterization of Medical Professional Liability Risks Associated With Transesophageal Echocardiography. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2019 Mar:32(3):359-364. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2018.11.003. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30679140]

Huu Vinh V, Viet Dang Quang N, Van Khoi N. Surgical management of esophageal perforation: role of primary closure. Asian cardiovascular & thoracic annals. 2019 Mar:27(3):192-198. doi: 10.1177/0218492319827439. Epub 2019 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 30665318]

Onodera Y, Nakano T, Fukutomi T, Naitoh T, Unno M, Shibata C, Kamei T. Thoracoscopic Esophagectomy for a Patient With Perforated Esophageal Epiphrenic Diverticulum After Kidney Transplantation: A Case Report. Transplantation proceedings. 2018 Dec:50(10):3964-3967. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2018.08.042. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30577297]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGhiselli A, Bizzarri B, Ferrari D, Manzali E, Gaiani F, Fornaroli F, Nouvenne A, Di Mario F, De'Angelis GL. Endoscopic dilation in pediatric esophageal strictures: a literature review. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis. 2018 Dec 17:89(8-S):27-32. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i8-S.7862. Epub 2018 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 30561414]

Milosavljevic T, Popovic D, Zec S, Krstic M, Mijac D. Accuracy and Pitfalls in the Assessment of Early Gastrointestinal Lesions. Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 2019:37(5):364-373. doi: 10.1159/000495849. Epub 2018 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 30540998]

Kupeli M, Dogan A. Successful Treatment of a Late Diagnosed Esophageal Perforation with Mediastinitis and Pericardial Abscess. Journal of the College of Physicians and Surgeons--Pakistan : JCPSP. 2018 Dec:28(12):972-973. doi: 10.29271/jcpsp.2018.12.972. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30501839]

Aiolfi A, Ferrari D, Riva CG, Toti F, Bonitta G, Bonavina L. Esophageal foreign bodies in adults: systematic review of the literature. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2018 Oct-Nov:53(10-11):1171-1178. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2018.1526317. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 30394140]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWatkins JR, Farivar AS. Endoluminal Therapies for Esophageal Perforations and Leaks. Thoracic surgery clinics. 2018 Nov:28(4):541-554. doi: 10.1016/j.thorsurg.2018.07.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30268300]

Zhong S, Wu Z, Wang Z. Successful Treatment of Fishbone-Induced Esophageal Perforation and Mediastinal Abscess: A Case Report and Literature Review. The American journal of case reports. 2023 Dec 18:24():e942056. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.942056. Epub 2023 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 38105546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSusai CJ, Banks KC, Alcasid NJ, Velotta JB. A clinical review of spontaneous pneumomediastinum. Mediastinum (Hong Kong, China). 2024:8():4. doi: 10.21037/med-23-25. Epub 2023 Oct 27 [PubMed PMID: 38322193]

Sdralis EIK, Petousis S, Rashid F, Lorenzi B, Charalabopoulos A. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and management of esophageal perforations: systematic review. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2017 Aug 1:30(8):1-6. doi: 10.1093/dote/dox013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28575240]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDanielian SN, Tarabrin EA, Rabadanov KM, Barmina TG, Kvardakova OV, Khachatryan SA. [Post-intubation rupture of thoracic trachea in a patient with iatrogenic esophageal perforation and mediastinitis]. Khirurgiia. 2023:(1):89-93. doi: 10.17116/hirurgia202301189. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36583499]

Andrási K, Stankovics P, Kecskés L. [Diagnosis and treatment of traumatic esophageal perforation.]. Orvosi hetilap. 2023 Oct 29:164(43):1719-1724. doi: 10.1556/650.2023.32859. Epub 2023 Oct 29 [PubMed PMID: 37898911]

Luttikhold J, Pattynama LMD, Seewald S, Groth S, Morell BK, Gutschow CA, Ida S, Nilsson M, Eshuis WJ, Pouw RE. Endoscopic vacuum therapy for esophageal perforation: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2023 Sep:55(9):859-864. doi: 10.1055/a-2042-6707. Epub 2023 Feb 24 [PubMed PMID: 36828030]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVeziant J, Boudis F, Lenne X, Bruandet A, Eveno C, Nuytens F, Piessen G. Outcomes Associated With Esophageal Perforation Management: Results From a French Nationwide Population-based Cohort Study. Annals of surgery. 2023 Nov 1:278(5):709-716. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000006048. Epub 2023 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 37497641]

Singh NP, Rizk JG. Oesophageal perforation following ingestion of over-the-counter ibuprofen capsules. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2008 Aug:122(8):864-6. doi: 10.1017/S0022215108002582. Epub 2008 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 18452637]

Nassour I, Fang SH. Gastrointestinal perforation. JAMA surgery. 2015 Feb:150(2):177-8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.358. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25549241]

Schmitz RJ, Sharma P, Badr AS, Qamar MT, Weston AP. Incidence and management of esophageal stricture formation, ulcer bleeding, perforation, and massive hematoma formation from sclerotherapy versus band ligation. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2001 Feb:96(2):437-41 [PubMed PMID: 11232687]

Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, Marshall MB, Kaiser LR, Kucharczuk JC. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2004 Apr:77(4):1475-83 [PubMed PMID: 15063302]

Axtell AL, Gaissert HA, Morse CR, Premkumar A, Schumacher L, Muniappan A, Ott H, Allan JS, Lanuti M, Mathisen DJ, Wright CD. Management and outcomes of esophageal perforation. Diseases of the esophagus : official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus. 2022 Jan 7:35(1):. pii: doab039. doi: 10.1093/dote/doab039. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34212186]