Introduction

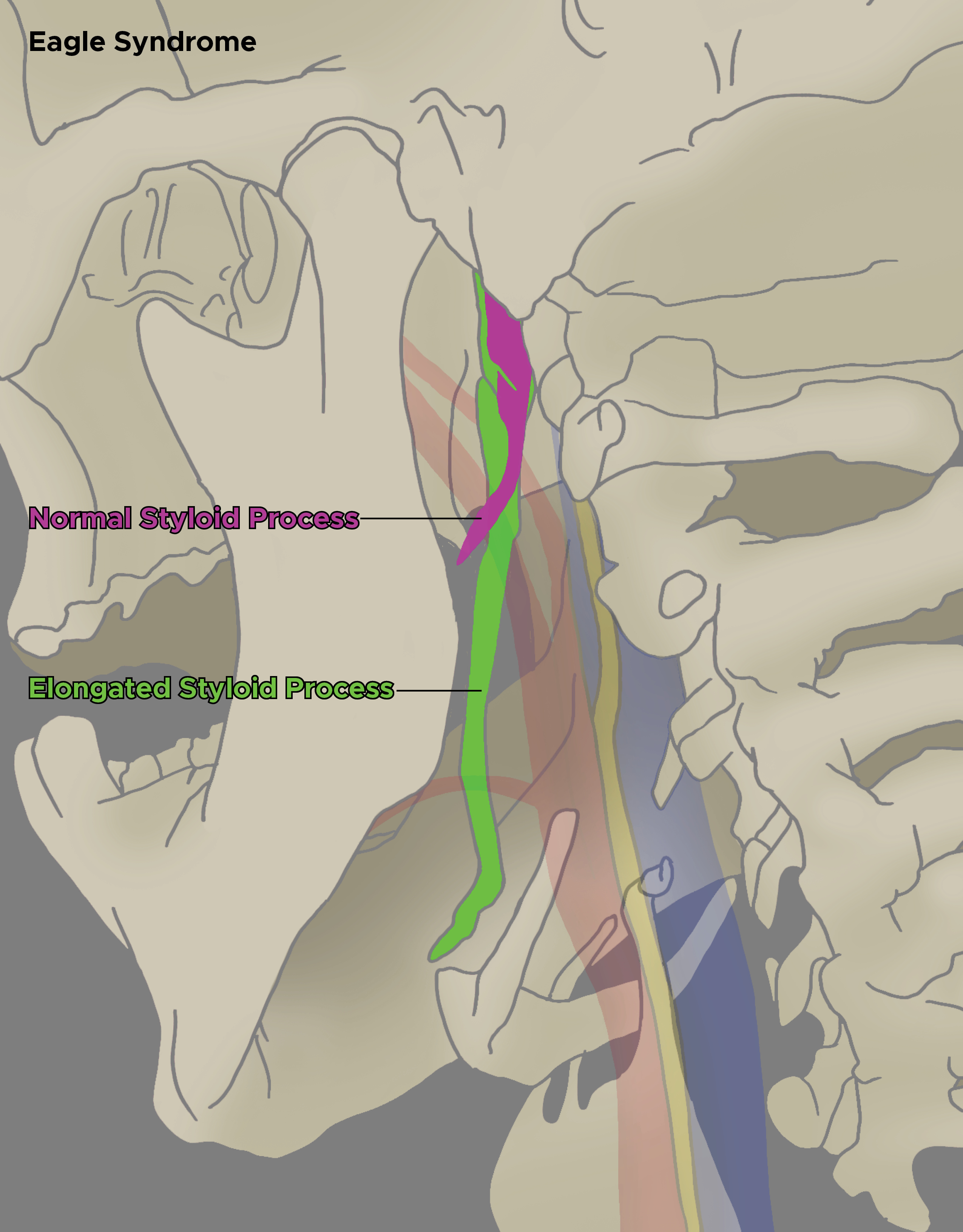

Eagle syndrome was named after Watt W. Eagle, an otolaryngologist at Duke University, who described the first cases in 1937. It is a rare condition caused by an elongated or disfigured styloid process, which interferes with the functioning of neighboring structures and gives rise to orofacial and cervical pain often triggered by neck movements. Eagle syndrome is also referred to as stylohyoid syndrome, styloid syndrome, or styloid–carotid artery syndrome by some authors.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There is debate regarding the etiology of Eagle syndrome. Dr. Watt Eagle proposed that surgical trauma (tonsillectomy) or local chronic irritation causes osteitis, periostitis, or tendonitis of the styloid process and the stylohyoid ligaments, which resulted in reactive, ossifying hyperplasia. Later Lentini (1975) suggested the hypothesis that persistent mesenchymal elements, also known as Reichert cartilage residues, could undergo osseous metaplasia in the setting of an appropriate traumatic or stressful event. Epifanio, in 1962, considered that the ossification of the styloid process was also corresponding to endocrine disorders in women at menopause, who also had ossification of other ligaments in the body. Gokce C et al. (2008) reported that patients with end-stage renal disease having abnormal calcium, phosphorus, and vitamin D metabolism had heterotopic calcification, which caused elongation of the styloid process and, thus, the presentation of Eagle syndrome. Finally, a retrospective study by Sekerci in 2015 indicated that a relationship exists between the presence of an arcuate foramen and an elongated styloid process. Results were derived from data from 542 patients employing three-dimensional CT scans.[4][5]

Epidemiology

Early on, Eagle reported that the normal styloid process was ~2.5 cm in length, and any process longer than 2.5 cm might be considered abnormally elongated. Later in a postmortem study of 80 cadavers, the length of the styloid process was found to range from 1.52 to 4.77 cm. An elongated styloid process is incidental in about 4% of the general population, but of these, only about 4% present with symptoms that are attributable to the elongation of styloid; therefore, the true incidence is about 0.16%, with a female-to-male predominance of 3:1. Patients are usually greater than 30 years of age, and this is usually a bilateral process (although unilateral cases are also seen).[6][7]

Pathophysiology

Previously it was hypothesized that the formation of scar tissue around the styloid apex after tonsillectomy caused compression and straining of the neurovascular structures present in the retro styloid compartment. However, Eagle syndrome also presents in patients who have never been operated on for tonsillectomy. Several possible mechanisms for the pathogenesis of pain in Eagle syndrome have been proposed. The first considers that the elongated styloid process causes compression of cranial nerves, most commonly the glossopharyngeal nerve, with subsequent throat and neck pain. Alternatively, there is the possibility of compression of the internal carotid artery by the styloid process, which can cause transient ischemic attacks or compression of the sympathetic nerves running along the artery, leading to an array of symptoms. The pain in Eagle syndrome often resembles glossopharyngeal neuralgia but is typically more dull and constant. However, cases with sharp intermittent pain along the path of the glossopharyngeal nerve have also been reported. Furthermore, theories of reactive hyperplasia and reactive metaplasia exist, which associate the elongation with either overgrowth of the styloid process itself or ossification of the stylohyoid ligament complex as a consequence of trauma. This phenomenon may explain the incidence of Eagle syndrome in patients after tonsillectomy, as it was originally described by Eagle. Other possible considered causes are the abnormal angulation associated with an abnormally lengthy styloid process causing irritation of adjacent musculature or mucosa. Stretching and fibrosis involving the fifth, seventh, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves in the post-tonsillectomy period could also be a possible etiology. Finally, the symptoms may be a result of the normal process of aging. As normal aging is associated with a decrease in elasticity of soft tissues, degenerative and inflammatory changes in the tendinous portion of the stylohyoid insertion, a condition called insertion tendinosis, may cause pain in the distribution of glossopharyngeal nerve resembling Eagle syndrome. To avoid confusion, this manifestation better is called pseudo-stylohyoid syndrome.[8][9]

History and Physical

Clinically, the syndrome is most frequently seen in the third or fourth decades. Although there is no significant sex predilection in the occurrence of mineralization of the styloid process, symptoms are more common in women. In Eagle syndrome, the symptoms range from mild discomfort to acute neurologic and referred pain. Symptoms are divided into two groups. The first group of symptoms, also called the “classic Eagle syndrome,” is usually encountered in patients after pharyngeal trauma or tonsillectomy. It is characterized by pain located in the areas where the fifth, seventh, eighth, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves are distributed. As mentioned earlier, pain is presumably a consequence of stretching or compression of the cranial nerves V, VII, VIII, IX, or X or their nerve endings in the tonsillar fossa during healing (scar tissue). Although an elongated styloid process may cause episodic tic-like pain attacks that are typical of glossopharyngeal neuralgia, most patients present with a constant dull pharyngeal pain, focused in the ipsilateral tonsillar fossa, that can be referred to the ear and aggravated by rotation of the head. Other symptoms include the sensation of a foreign body in the pharynx (55%), difficulty swallowing(dysphagia), painful swallowing, otalgia, headache, pain along with the distribution of the external and internal carotid arteries, pain on cervical rotation or mastication, facial pain, and tinnitus. Further, a mass or bulge may be palpated in the ipsilateral tonsillar fossa, exacerbating the patient’s symptoms. Classic Eagle syndrome usually presents on only one side. However, it may rarely have a bilateral presentation. The other group of symptoms is attributed to vascular Eagle syndrome, or stylocarotid syndrome, which is a consequence of compression of the internal or external carotid artery (along with their perivascular sympathetic fibers) by a laterally or medially deviated styloid process. In these cases, turning the head can cause compression of the artery, which causes pain along with the distribution of the artery. This can potentially lead to TIAs, vertigo, and syncope. Usually, there is no history of tonsillectomy. In the case of impingement of the internal carotid artery, pain is often referred to the supraorbital region. In the case of external carotid artery irritation, the pain radiates to the infraorbital region.

Evaluation

The diagnosis of Eagle syndrome is based on an optimal medical history and physical examination. Pain in the throat that radiates to the neck, ear, or face is often nonspecific and can be caused by several conditions, for instance, upper aerodigestive tract malignancies, neuralgia, and temporomandibular joint dysfunction. These should be excluded before considering Eagle syndrome. It usually presents with a characteristic dull and throbbing pain of an elongated styloid process that aggravates with deglutition and can be duplicated by palpation of the tonsillar fossa. Insertion tendonitis can resemble Eagle syndrome. However, it usually causes tenderness over the greater horn of the hyoid bone. An elongated styloid process can be palpated by intraoral palpation, placing the index finger in the tonsillar fossa, and applying gentle pressure. If the pain is reproduced by palpation and either referred to the ear, face, or head, the diagnosis of an elongated styloid process is most likely. A styloid process of normal length is usually impalpable. The diagnosis of the elongated styloid process is then confirmed by imaging. Several imaging techniques have been employed, but CT is the most accurate. 3-D CT reconstruction of the neck enables precise measurement of the length of the styloid process and the ossified stylohyoid ligament. The normal length of the adult styloid is approximately 2.5 cm, while greater than 3 cm is considered elongated. If this criterion is used, almost 4% of the population have an elongated process. However, only a small proportion (4-10%) is symptomatic. Orthopantomogram (OPG) and CT can both be used to assess the styloid process/stylohyoid ligament complex. In cases where mechanical vascular compression is potentially the cause of ischemic symptoms, angiographic examination (CT angiography or catheter angiography) should be obtained with the patient's head appropriately positioned to reproduce symptoms that may demonstrate mechanical stenosis of the carotid artery.

Treatment / Management

The elongated styloid process syndrome can be managed either conservatively or surgically. Conservative treatments include analgesics, antidepressant medications, anticonvulsants, transpharyngeal injection of steroids and lidocaine, diazepam, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and the application of topical heat. Trans pharyngeal manipulation with a manual fracture of the elongated styloid process does not usually relieve symptoms and risks damage to adjacent neurovascular structures. Patients who fail to respond to multiple medications may require surgical manipulations. The most effective treatment is the surgical shortening of the styloid process, either via an intraoral or external approach, as it produces better long-term results. The advantages of an intraoral approach are the simplicity of the technique, reduced operation time, achievability under local anesthesia, and absence of any visible external scar. However, the main disadvantages are a lack of access, particularly if there are a subsequent hemorrhage and deep neck infections, poor visualization of the surgical field, especially in patients with significantly reduced jaw opening, the risk of iatrogenic injury to major neurovascular structures, alterations of speech and swallowing from postoperative edema. The most significant advantage of an external approach is enhanced exposure of the styloid process and the adjacent structures, which overshadow all other benefits. It also aids in the removal of a partially ossified stylohyoid ligament. Major disadvantages include more time consumption, the hazard of injury to the facial nerve and its branches, disfiguring neck scar, and longer recovery period. In most cases, however, this choice is usually based on the surgical specialty of the conducting surgeon. Surgical failures in up to 20% of patients have been reported.[10][11][12]

Differential Diagnosis

- Cervical arthritis

- Cervical mass

- Faulty dental prostheses

- Migraine-type headaches

- Esophageal diverticula

- Otitis

- Possible tumors

- Salivary gland disease

- Temporal arteritis

- Trigeminal neuralgia

Pearls and Other Issues

The symptoms related to Eagle syndrome can be confused with a wide variety of facial neuralgias or oral, dental, and temporomandibular diseases, hyoid bursitis, cervical arthritis, temporal arteritis, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, carotid artery dissection, and possible head and neck tumors.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of Eagle syndrome is complicated. The disorder can be confused with many other pain syndromes. Further, its treatment is complex and best undertaken with a multidisciplinary team, including pharmacists. Drug therapy can be used to relieve pain. Surgery to excise the elongated styloid is done but is fraught with complications like injury to the facial nerve.

Clinicians should always consider conservative therapies first. Outcomes remain unknown because not many cases exist in the literature.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Abuhaimed AK, Alvarez R, Menezes RG. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Styloid Process. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082019]

Zhang FL, Zhou HW, Guo ZN, Yang Y. Eagle Syndrome as a Cause of Cerebral Venous Sinus Thrombosis. The Canadian journal of neurological sciences. Le journal canadien des sciences neurologiques. 2019 May:46(3):344-345. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2019.17. Epub 2019 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 30932799]

Qureshi S, Farooq MU, Gorelick PB. Ischemic Stroke Secondary to Stylocarotid Variant of Eagle Syndrome. The Neurohospitalist. 2019 Apr:9(2):105-108. doi: 10.1177/1941874418797763. Epub 2018 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 30915189]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 30896522]

Omami G. Retromandibular Pain Associated With Eagle Syndrome. Headache. 2019 Jun:59(6):915-916. doi: 10.1111/head.13502. Epub 2019 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 30883724]

Zammit M, Chircop C, Attard V, D'Anastasi M. Eagle's syndrome: a piercing matter. BMJ case reports. 2018 Nov 28:11(1):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226611. Epub 2018 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30567108]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePéus D, Kollias SS, Huber AM, Huber GF. Recurrent unilateral peripheral facial palsy in a patient with an enlarged styloid process. Head & neck. 2019 Mar:41(3):E34-E37. doi: 10.1002/hed.25384. Epub 2018 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 30584676]

Montevecchi F, Caranti A, Cammaroto G, Meccariello G, Vicini C. Transoral Robotic Surgery (TORS) for Bilateral Eagle Syndrome. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 2019:81(1):36-40. doi: 10.1159/000493736. Epub 2018 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 30537726]

Sullivan T, Rosenblum J. Eagle syndrome: Transient ischemic attack and subsequent carotid dissection. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2018 Oct-Nov:97(10-11):342-344 [PubMed PMID: 30481841]

Caylakli F. Important factor for pain relief in patients with eagle syndrome: Excision technique of styloid process. American journal of otolaryngology. 2019 Mar-Apr:40(2):337. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2018.10.009. Epub 2018 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 30477910]

Hettiarachchi PVKS, Jayasinghe RM, Fonseka MC, Jayasinghe RD, Nanayakkara CD. Evaluation of the styloid process in a Sri Lankan population using digital panoramic radiographs. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research. 2019 Jan-Mar:9(1):73-76. doi: 10.1016/j.jobcr.2018.10.001. Epub 2018 Oct 4 [PubMed PMID: 30302305]

Shereen R, Gardner B, Altafulla J, Simonds E, Iwanaga J, Litvack Z, Loukas M, Shane Tubbs R. Pediatric glossopharyngeal neuralgia: a comprehensive review. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2019 Mar:35(3):395-402. doi: 10.1007/s00381-018-3995-3. Epub 2018 Oct 25 [PubMed PMID: 30361762]