Introduction

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is a broad term that describes irregularities in the menstrual cycle involving frequency, regularity, duration, and volume of flow outside of pregnancy. Up to one-third of women will experience abnormal uterine bleeding in their life, with irregularities most commonly occurring at menarche and perimenopause. A normal menstrual cycle has a frequency of 24 to 38 days and lasts 2 to 7 days, with 5 to 80 milliliters of blood loss. Variations in any of these 4 parameters constitute abnormal uterine bleeding. Older terms such as oligomenorrhea, menorrhagia, and dysfunctional uterine bleeding should be discarded in favor of using simple terms to describe the nature of abnormal uterine bleeding. Revisions to the terminology were first published in 2007, followed by updates from the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) in 2011 and 2018. The FIGO systems first define abnormal uterine bleeding, then give an acronym for common etiologies. These descriptions apply to chronic, nongestational AUB. In 2018, the committee added intermenstrual bleeding and defined irregular bleeding as outside the 75th percentile.[1]

Abnormal uterine bleeding can also be divided into acute versus chronic. Acute AUB is excessive bleeding that requires immediate intervention to prevent further blood loss. Acute AUB can occur on its own or superimposed on chronic AUB, which refers to irregularities in menstrual bleeding for most of the previous 6 months.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

PALM-COEIN is a useful acronym provided by the International Federation of Obstetrics and Gynecology (FIGO) to classify the underlying etiologies of abnormal uterine bleeding. The first portion, PALM, describes structural issues. The second portion, COEI, describes non-structural issues. The N stands for "not otherwise classified."

- P: Polyp

- A: Adenomyosis

- L: Leiomyoma

- M: Malignancy and hyperplasia

- C: Coagulopathy

- O: Ovulatory dysfunction

- E: Endometrial disorders

- I: Iatrogenic

- N: Not otherwise classified

One or more of the problems listed above can contribute to a patient's abnormal uterine bleeding. Some structural entities, such as endocervical polyps, endometrial polyps, or leiomyomas, may be asymptomatic and not the primary cause of a patient's AUB.

In the 2018 FIGO system, AUB secondary to anticoagulants was moved from the coagulopathy category to the iatrogenic category.

Conditions to be included in the not otherwise classified category include pelvic inflammatory disease, chronic liver disease, and cervicitis.

AUB not otherwise classified contains rare etiologies and includes arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), myometrial hyperplasia, and endometritis.[1]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of abnormal uterine bleeding among reproductive-aged women internationally is estimated to be between 3% to 30%, with a higher incidence occurring around menarche and perimenopause. Many studies are limited to heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), but when irregular and intermenstrual bleeding are considered, the prevalence rises to 35% or greater.[1] Many women do not seek treatment for their symptoms, and some components of diagnosis are objective while others are subjective, making exact prevalence difficult to determine.[3]

Pathophysiology

The uterine and ovarian arteries supply blood to the uterus. These arteries become the arcuate arteries; then, the arcuate arteries send off radial branches which supply blood to the two layers of the endometrium, the functionality and basalis layers. Progesterone levels fall at the end of the menstrual cycle, leading to enzymatic breakdown of the functionalis layer of the endometrium. This breakdown leads to blood loss and sloughing, which makes up menstruation. Functioning platelets, thrombin, and vasoconstriction of the arteries to the endometrium control blood loss. Any derangement in the structure of the uterus (such as leiomyoma, polyps, adenomyosis, malignancy, or hyperplasia), derangements to the clotting pathways (coagulopathies or iatrogenically), or disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis (through ovulatory/endocrine disorders or iatrogenically) can affect menstruation and lead to abnormal uterine bleeding.[4]

History and Physical

The clinician should obtain a detailed history from a patient who presented with complaints related to menstruation. Specific aspects of the history include:

- Menstrual history

- Age at menarche

- Last menstrual period

- Menses frequency, regularity, duration, the volume of flow

- Frequency can be described as frequent (less than 24 days), normal (24 to 38 days), or infrequent (greater than 38 days)

- Regularity can be described as absent, regular (with a variation of +/- 2 to 7 days), or irregular (variation greater than 20 days)

- The duration can be described as prolonged (greater than 8 days), normal (approximately 4 to 8 days), or shortened (less than 4 days)

- The volume of flow can be described as heavy (greater than 80 mL), normal (5 to 80 mL), or light (less than 5 mL of blood loss)

- Exact volume measurements are difficult to determine outside research settings; therefore, detailed questions regarding frequency of sanitary product changes during each day, passage and size of any clots, need to change sanitary products during the night, and a "flooding" sensation is important.[5]

- Intermenstrual and postcoital bleeding

- Sexual and reproductive history

- Obstetrical history, including the number of pregnancies and mode of delivery

- Fertility desire and subfertility

- Current contraception

- History of sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- PAP smear history

- Associated symptoms/Systemic symptoms

- Weight loss

- Pain

- Discharge

- Bowel or bladder symptoms

- Signs/symptoms of anemia

- Signs/symptoms or history of a bleeding disorder

- Signs/symptoms or history of endocrine disorders

- Current medications

- Family history, including questions concerning coagulopathies, malignancy, endocrine disorders

- Social history, including tobacco, alcohol, and drug uses; occupation; the impact of symptoms on quality of life

- Surgical history

The physical exam should include:

- Vital signs, including blood pressure and body mass index (BMI)

- Signs of pallor, such as skin or mucosal pallor

- Signs of endocrine disorders

- Examination of the thyroid for enlargement or tenderness

- Excessive or abnormal hair growth patterns, clitoromegaly, acne, potentially indicating hyperandrogenism

- Moon facies, abnormal fat distribution, striae that could indicate Cushing syndrome

- Signs of coagulopathies, such as bruising or petechiae

- Abdominal exam to palpate for any pelvic or abdominal masses

- Pelvic exam: Speculum and bimanual

- Pap smear, if indicated

- STI screening (such as for gonorrhea and chlamydia) and wet prep if indicated

- Endometrial biopsy, if indicated[4]

Evaluation

Laboratory testing can include but is not limited to a urine pregnancy test, complete blood count, ferritin, coagulation panel, thyroid function tests, gonadotropins, and prolactin.

Imaging studies can include transvaginal ultrasound, MRI, and hysteroscopy. Transvaginal ultrasound does not expose the patient to radiation and can show uterus size and shape, leiomyomas (fibroids), adenomyosis, endometrial thickness, and ovarian anomalies. It is an important tool and should be obtained early in the investigation of abnormal uterine bleeding. MRI provides detailed images that can prove useful in surgical planning, but it is costly and not the first-line choice for imaging in patients with AUB. Hysteroscopy and sonohysterography (transvaginal ultrasound with intrauterine contrast) are helpful in situations where endometrial polyps are noted, images from transvaginal ultrasound are inconclusive, or submucosal leiomyomas are seen. Hysteroscopy and sonohysterography are more invasive but can often be performed in office settings.

Endometrial tissue sampling may not be necessary for all women with AUB but should be performed on women at high risk for hyperplasia or malignancy. An endometrial biopsy is considered the first-line test in women with AUB who are 45 years or older. Endometrial sampling should also be performed in women younger than 45 with unopposed estrogen exposure, such as women with obesity and/or polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), as well as a failure of treatment or persistent bleeding.[2]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding depends on multiple factors, such as the etiology of the AUB, fertility desire, the clinical stability of the patient, and other medical comorbidities. Treatment should be individualized based on these factors. In general, medical options are preferred as initial treatment for AUB.

For acute abnormal uterine bleeding, hormonal methods are the first line in medical management. Intravenous (IV) conjugated equine estrogen, combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), and oral progestins are all options for treating acute AUB. Tranexamic acid prevents fibrin degradation and can be used to treat acute AUB. Tamponade of uterine bleeding with a Foley bulb is a mechanical option for the treatment of acute AUB. It is important to assess the patient's clinical stability and replace volume with intravenous fluids and blood products while attempting to stop the acute abnormal uterine bleeding. Desmopressin, administered intranasally, subcutaneously, or intravenously, can be given for acute AUB secondary to the coagulopathy von Willebrand disease. Some patients may require dilation and curettage.

Based on the PALM-COEIN acronym for etiologies of chronic AUB, specific treatment options for each category are listed below:

Polyps are treated through surgical resection.

Adenomyosis is treated via hysterectomy. Less often, adenomyomectomy is performed.

Leiomyomas (fibroids) can be treated through medical or surgical management depending on the patient's desire for fertility, medical comorbidities, pressure symptoms, and distortion of the uterine cavity. Surgical options include uterine artery embolization, endometrial ablation, or hysterectomy. Medical management options include a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (IUD), GnRH agonists, systemic progestins, and tranexamic acid with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Malignancy or hyperplasia can be treated through surgery, +/- adjuvant treatment depending on the stage, progestins in high doses when surgery is not an option, or palliative therapy, such as radiotherapy.

Coagulopathies leading to AUB can be treated with tranexamic acid or desmopressin (DDAVP).

Ovulatory dysfunction can be treated through lifestyle modification in women with obesity, PCOS, or other conditions in which anovulatory cycles are suspected. Endocrine disorders should be corrected using appropriate medications, such as cabergoline for hyperprolactinemia and levothyroxine for hypothyroidism.

Endometrial disorders have no specific treatment, as mechanisms are not clearly understood.

Iatrogenic causes of AUB should be managed based on the offending drug and/or drugs. If a certain contraception method is the suspected culprit for AUB, alternative methods can be considered, such as the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, combined oral contraceptive pills (in monthly or extended cycles), or systemic progestins. If other medications are suspected and cannot be discontinued, the aforementioned methods can also help control AUB. Individual therapy should be tailored based on a patient's reproductive wishes and medical comorbidities.

Not otherwise classified causes of AUB include entities such as endometritis and AVMs. Endometritis can be treated with antibiotics and AVMs with embolization.[2][4][5](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Any bleeding from the genitourinary tract or gastrointestinal tract (GI tract) can mimic abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, bleeding from other sources fits into the differential diagnosis and must be ruled out.

The differential diagnosis for genital tract bleeding based on anatomic location or system:

- Vulva: Benign growths or malignancy

- Vagina: Benign growths, sexually transmitted infections, vaginitis, malignancy, trauma, foreign bodies

- Cervix: Benign growths, sexually transmitted infections, malignancy

- Fallopian tubes and ovaries: Pelvic inflammatory disease, malignancy

- Urinary tract: Infections, malignancy

- Gastrointestinal tract: Inflammatory bowel disease, Behçet syndrome

- Pregnancy complications: Spontaneous abortion, ectopic pregnancy, placenta previa

- Uterus: Etiologies of bleeding arising from the uterine corpus are listed in the acronym PALM-COEIN[1][2][6]

Prognosis

The prognosis for abnormal uterine bleeding is favorable but also depends on the etiology. The main goal of evaluating and treating chronic AUB is to rule out serious conditions such as malignancy and improve the patient's quality of life, keeping in mind current and future fertility goals and other comorbid medical conditions that may impact treatment or symptoms. Prognosis also differs based on medical versus surgical treatment. Non-hormonal treatment with anti-fibrinolytic and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications has been shown to reduce blood loss during menstruation by up to 50%.[5] Oral contraceptive pills can be effective, but there is a lack of data from randomized trials. For women with heavy menstrual bleeding as their primary symptom of AUB, the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD has been proven to be more effective than other medical therapies and improves the patient's quality of life. Injectable progestogens and GnRH agonists can produce amenorrhea in up to 50% and 90% of women, respectively. However, injectable progestogens can produce the side effect of breakthrough bleeding, and GnRH agonists are usually only used for a 6-month course due to their side effects in producing a low estrogen state.[5]

With the surgical techniques, randomized clinical trials and reviews have shown that endometrial ablation controlled bleeding more effectively at 4 months postoperatively, but at 5 years, there was no difference compared to medical management. When trials have compared hysterectomy versus levonorgestrel-releasing IUD, the hysterectomy group had better results at 1 year. There was no difference in the quality of life seen at 5 and 10 years, but many women in the levonorgestrel-releasing IUD group had undergone a hysterectomy by 10 years.[5]

Complications

Complications of chronic abnormal uterine bleeding can include anemia, infertility, and endometrial cancer. Acute abnormal uterine bleeding, severe anemia, hypotension, shock, and even death may result if prompt treatment and supportive care are not initiated.

Consultations

Consultations with obstetrics and gynecology should be initiated early on for proper evaluation and treatment. Depending on the etiology of abnormal uterine bleeding, other specialties may need to become involved in patient care. For coagulopathies, consultations with hematology/oncology are warranted. If the patient wishes to undergo a uterine artery embolization, Interventional radiology will need to be consulted. Malignancy may require both gynecologic oncology and hematology/oncology specialties for proper treatment.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Worldwide, many women do not report abnormal uterine bleeding to their healthcare providers, so it is important to foster an environment of open discussion on menstruation. Primary care physicians should ask women about their last menstrual cycle, regularity, desire for fertility, contraception, and sexual health. If abnormal uterine bleeding can be identified at the primary care level, then further history, examination, and testing can be performed, and the proper consultations can be arranged.

Patients with abnormal uterine bleeding should be educated on any pertinent lifestyle changes, treatment options, and when to seek emergency care.

Pearls and Other Issues

Abnormal uterine bleeding is common among women worldwide. A detailed history is an important first step in evaluating a woman who presents with AUB, and clinicians should be familiar with the normal pattern of menstruation, including frequency, regularity, duration, and volume of flow. After a detailed history is obtained and a physical exam is performed, further tests and imaging may be warranted depending on the suspected etiology. PALM COEIN is a useful acronym for common etiologies of AUB, with PALM representing structural causes (polyps, adenomyosis, leiomyomas, and malignancy or hyperplasia) and COEIN representing non-structural causes (coagulopathies, ovulatory disorders, endometrial disorders, iatrogenic causes, and not otherwise classified). Women older than 45 years of age or women younger than 45 with risk factors for malignancy require endometrial sampling as part of the evaluation for AUB. Treatment is based on etiology, desire for fertility, and medical comorbidities.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Health professionals should coordinate care in an interprofessional approach to evaluate and treat women with abnormal uterine bleeding. Nurses and physicians in primary care, such as family medicine and internal medicine, might be the first to discover AUB and should consult with obstetrics and gynecology early on. Patients should be informed of all of their options for control of AUB based on etiology. A detailed discussion concerning the desire for fertility, medical versus surgical management, and prognosis should be conducted. Physicians and pharmacists should educate patients concerning any possible side effects of medical management.

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) has published a summary of recommendations and conclusions concerning abnormal uterine bleeding. [6]

Level A Recommendations (Level I evidence or consistent findings from multiple studies of levels II, III, or IV):

- Sonohysterography is superior to transvaginal ultrasound in detecting intracavitary lesions, such as polyps or submucosal leiomyomas.

- For all adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding and adults with a positive screening history for a bleeding disorder, lab tests should be performed, including a CBC with platelets, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time; bleeding time is neither sensitive nor specific and is not indicated.

Level B Recommendations (Levels II, III, IV evidence and findings are generally consistent):

- Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis should be considered in patients at high risk of infection.

- Hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism are associated with AUB. Screening for thyroid disease with TSH in women with AUB is reasonable and inexpensive.

Level C Recommendations (Levels II, III, or IV evidence, but findings are inconsistent):

- Endometrial sampling should be performed in patients with AUB older than 45 years as a first-line test.

- The ACOG supports adopting the PALM-COEIN nomenclature system developed by FIGO to standardize the terminology used to describe AUB.

- Some experts recommend transvaginal ultrasound as the initial screening test for AUB and MRI as second-line options when the diagnosis is inconclusive. Further delineation would affect patient management, or coexisting uterine myomas are suspected.

- MRI may be useful to guide the treatment of myomas, particularly when the uterus is enlarged, contains multiple myomas, or precise myoma mapping is clinically important. However, the benefits and costs must be weighed when considering its use.

- Persistent bleeding with a previous benign pathology, such as proliferative endometrium, usually requires further testing to rule out nonfocal endometrial pathology or a structural pathology, such as a polyp or leiomyoma.

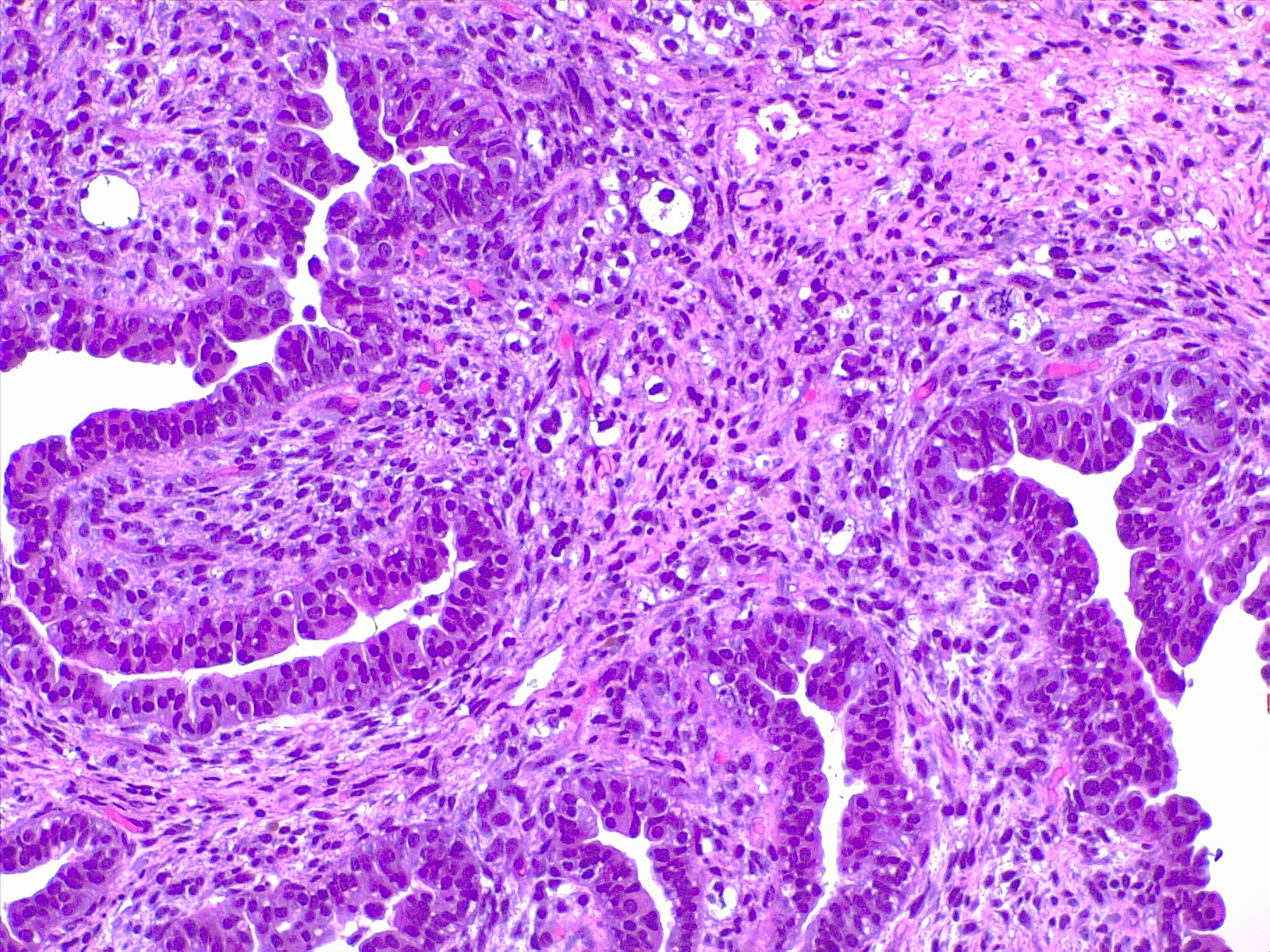

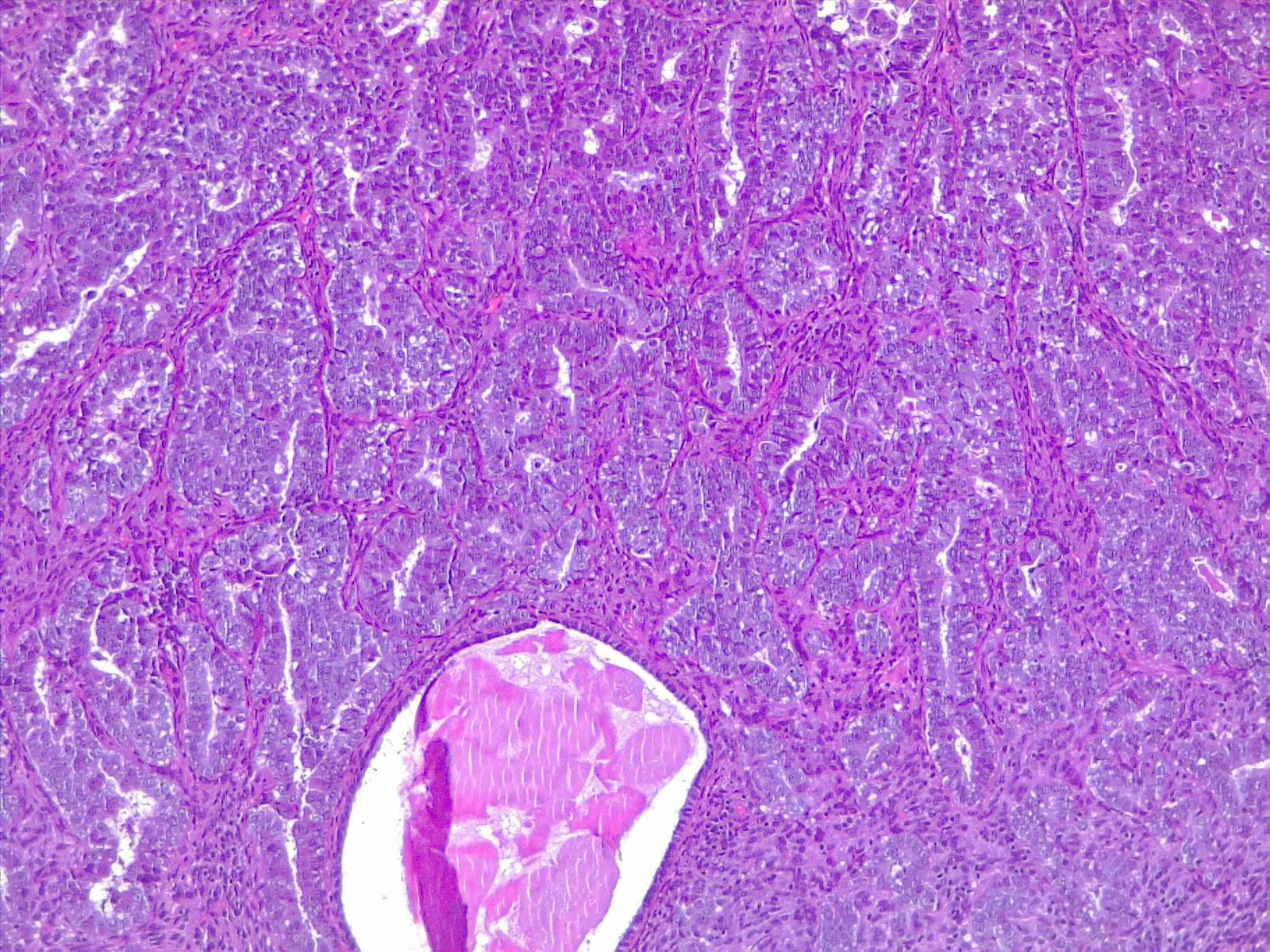

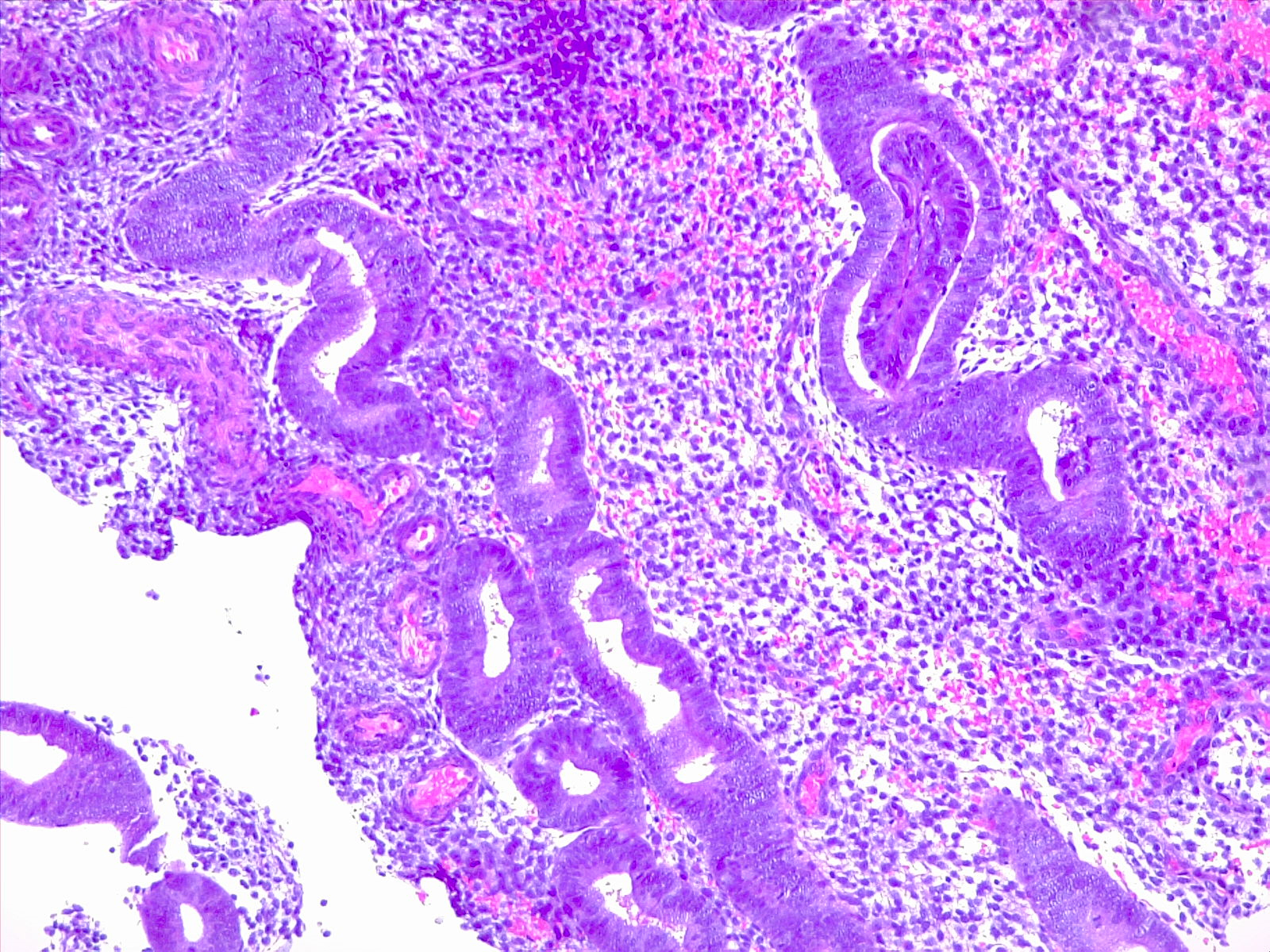

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Munro MG, Critchley HOD, Fraser IS, FIGO Menstrual Disorders Committee. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2018 Dec:143(3):393-408. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12666. Epub 2018 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 30198563]

. ACOG committee opinion no. 557: Management of acute abnormal uterine bleeding in nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Apr:121(4):891-896. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000428646.67925.9a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23635706]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu Z, Doan QV, Blumenthal P, Dubois RW. A systematic review evaluating health-related quality of life, work impairment, and health-care costs and utilization in abnormal uterine bleeding. Value in health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2007 May-Jun:10(3):183-94 [PubMed PMID: 17532811]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWhitaker L, Critchley HO. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2016 Jul:34():54-65. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.11.012. Epub 2015 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 26803558]

Cheong Y, Cameron IT, Critchley HOD. Abnormal uterine bleeding. British medical bulletin. 2017 Sep 1:123(1):103-114. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldx027. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28910998]

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice bulletin no. 128: diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-aged women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Jul:120(1):197-206. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318262e320. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22914421]