Introduction

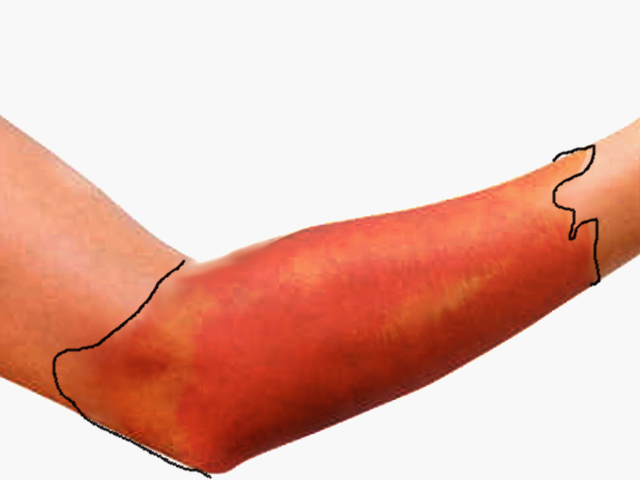

Cellulitis is a common bacterial skin infection, with over 14 million cases occurring in the United States annually. It accounts for approximately 3.7 billion dollars in ambulatory care costs and 650000 hospitalizations annually.[1] Cellulitis typically presents as a poorly demarcated, warm, erythematous area with associated edema and tenderness to palpation. It is an acute bacterial infection causing inflammation of the deep dermis and surrounding subcutaneous tissue. The infection is without an abscess or purulent discharge. Beta-hemolytic streptococci typically cause cellulitis, generally group A streptococcus (i.e., Streptococcus pyogenes), followed by methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. Patients who are immunocompromised, colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, bitten by animals, or have comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus may become infected with other bacteria.[2] If the clinician correctly identifies and promptly treats cellulitis, it typically resolves with appropriate antibiotic treatment.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The skin serves as a protective barrier preventing normal skin flora and other microbial pathogens from reaching the subcutaneous tissue and lymphatic system. When a break in the skin occurs, it allows for normal skin flora and other bacteria to enter into the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. The introduction of these bacteria below the skin surface can lead to an acute superficial infection affecting the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue, causing cellulitis. Cellulitis most commonly results from infection with group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus (i.e., Streptococcus pyogenes).[3]

Risk factors for cellulitis include any culprit that could cause a breakdown in the skin barrier such as skin injuries, surgical incisions, intravenous site punctures, fissures between toes, insect bites, animal bites, and other skin infections.[4] Patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, venous insufficiency, peripheral arterial disease, and lymphedema are at higher risk of developing cellulitis.[5]

Epidemiology

Cellulitis is relatively common, and most often occurs in middle-aged and older adults. When comparing men and women, there is no statistically significant difference in the incidence of cellulitis. There are approximately 50 cases per 1000 patient-years.[6]

Pathophysiology

Cellulitis is characterized by erythema, warmth, edema, and tenderness to palpation resulting from cytokine and neutrophil response from bacteria breaching the epidermis. The cytokines and neutrophils are recruited to the affected area after bacteria have penetrated the skin leading to an epidermal response. This response includes the production of antimicrobial peptides and keratinocyte proliferation and is postulated to produce the characteristic exam findings in cellulitis.[7] Group A Streptococci, the most common bacteria to cause cellulitis, can also produce virulence factors such as pyrogenic exotoxins (A, B, C, and F) and streptococcal superantigen that can lead to a more pronounced and invasive disease.[8]

History and Physical

Patients with cellulitis will reveal an affected skin area typically with a poorly demarcated area of erythema. The erythematous area is often warm to the touch with associated swelling and tenderness to palpation. The patient may present with constitutional symptoms of generalized malaise, fatigue, and fevers.

When evaluating patients presenting with cellulitis, clinicians should ask for a complete history of the presenting illness, focusing on the context in which the patient noticed the skin changes or how the cellulitis began to occur. It is essential to ask patients if they: recently traveled, experienced any trauma or injuries, have a history of intravenous drug use, and/or have had insect or animal bites to the affected area. A complete and thorough past medical history should additionally be conducted to evaluate for possible chronic medical conditions that predispose patients to cellulitis, such as diabetes mellitus, venous stasis, peripheral vascular disease, chronic tinea pedis, and lymphedema.

The affected area should be thoroughly inspected to look for any area of skin breakdown. The area should be demarcated with a marker to monitor for continuous spread. The area should be palpated to feel for fluctuance that could indicate the formation of a possible abscess. When gently palpating the affected area, be sure to note any presence of warmth, tenderness, or purulent drainage.

Cellulitis can present on any area of the body, but most often affects the lower extremities. It is rarely bilateral. In lower extremity cellulitis, careful examination between interspaces of the toes should take place.[9] Additionally, if any extremities are affected, check for proper sensation and verify pulses are intact to monitor closely for compartment syndrome. One should also make a note of developing vesicles, bullae, or the presence of peau d'orange and lymphadenopathy.

Evaluation

Cellulitis is diagnosed clinically based on the presence of spreading erythematous inflammation of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. It characteristically presents with worsening erythema, edema, warmth, and tenderness. Two of the four criteria (warmth, erythema, edema, or tenderness) are required to make the diagnosis. Its most common presentation is on the lower extremities but can affect any area of the body. It is most often unilateral and rarely (if ever) presents bilaterally. The patient's skin should be thoroughly evaluated to find the potential source for the cellulitis by looking for microabrasions of the skin secondary to injuries, insect bites, pressure ulcers, or injection sites. If cellulitis is affecting the patient's lower extremities, careful evaluation should be made to look between the patient's toes for fissuring or tinea pedis. Additionally, it can affect the lymphatic system and cause underlying lymphadenopathy. The associated edema with cellulitis can lead to the formation of vesicles, bullae, and edema surrounding hair follicles leading to peau d'orange.

The Infectious Disease Society of America practice guidelines recommends against imaging the infected area except in patients with febrile neutropenia. Consider blood cultures only in patients that are immunocompromised, experienced an immersion injury or animal bite.[9] Blood cultures are also necessary when a patient has signs of systemic infection.[8]

Treatment / Management

Patients presenting with mild cellulitis and displaying no systemic signs of infection should be covered with antibiotics that target the treatment of streptococcal species. Though believed to be a less common cause, consider coverage of MSSA. The duration of oral antibiotic therapy should be for a minimum duration of 5 days. In nonpurulent cellulitis, patients should receive cephalexin 500 mg every 6 hours. If they have a severe allergic reaction to beta-lactamase inhibitors, treat with clindamycin 300 mg to 450 mg every 6 hours.

In patients with purulent cellulitis, methicillin-resistant staph aureus colonization, cellulitis associated with an abscess or extensive puncture wounds, or a history of intravenous drug use, patients should receive antibiotics that cover against methicillin-resistant staph aureus as well. Cellulitis with MRSA risk factors should be treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole 800 mg/160 mg twice daily for 5 days in addition to cephalexin 500 mg every 6 hours. If a patient has an allergy to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, treat with clindamycin 300 mg to 450 mg every 6 hours. A longer duration of antibiotic treatment may be a consideration in patients who show minimal improvement with antibiotic therapy within 48 hours.

Hospitalization with the induction of systemic antibiotics may be necessary for patients who: present with systemic signs of infection*, have failed outpatient treatment, are immunocompromised, exhibit rapidly progressing erythema, are unable to tolerate oral medications, or have cellulitis overlying or near an indwelling medical device.

Intravenous antibiotics should be initiated to cover against group A strep. Absent patient risk factors for MRSA, treat with intravenous cefazolin, and when able de-escalate to cephalexin for a total of 5 days of treatment. If risk factors for MRSA are present, initiate therapy with Vancomycin with subsequent de-escalation to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

In immunocompromised patients requiring hospitalization for parenteral antibiotics, broad-spectrum antimicrobial coverage may be necessary with vancomycin plus piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem.

The clinician should obtain blood cultures if a patient is exhibiting signs of systemic toxicity, has persistent cellulitis despite adequate treatment, has unique exposures such as animal bites or water-associated injuries.[10]

Atypical organisms can cause cellulitis in particular situations. If exposed to a dog or cat bite, patients are at risk for developing cellulitis secondary to Pasteurella multocida. If secondary to an injury involving exposure to water, such as a cut from an oyster shell, cellulitis can be caused by Vibrio vulnificus. Diabetic patients and patients with diabetic foot ulcers are at risk for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Immunocompromised patients are at risk for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Cryptococcus.

If patients have significant edema with a known cause for the edema, the underlying condition should receive proper treatment to decrease the amount of edema and prevent future episodes of cellulitis. Patients should be instructed to keep the affected area elevated.[9](A1)

* Two or more of these systemic inflammatory response criteria: fever (over 38 degrees C), tachycardia (heart rate exceeding 90 beats/min), tachypnea (respiratory rate over 20 breaths/min), leukocytosis (white blood cells in excess of 12000/mm) leukopenia (white blood cells under 4000/mm) or bandemia greater than or equal to 10%.[9](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Cellulitis is a frequently encountered infection of the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue, mainly affecting the lower extremities, but it can have many mimickers.

Erysipelas is sometimes considered a form of cellulitis. However, it is a more superficial infection affecting the upper dermis and superficial lymphatic system. Bright red erythema, elevation of the affected skin, and well-demarcated borders can help to diagnose erysipelas and distinguish it from cellulitis, which tends to be more mildly erythematous (pink) and flat with less distinct boundaries. Erysipelas may also have streaking when superficial lymphatics are involved. It most commonly results from the exotoxins released from group A strep (Streptococcus pyogenes). First-line treatment for erysipelas is amoxicillin or cephalexin.

Chronic venous stasis dermatitis is a long-standing, bilateral, inflammatory dermatosis secondary to chronic venous insufficiency and typically involves the medial malleoli. It appears on the lower extremities and manifests as erythema with scaling, peripheral edema, and hyperpigmentation. Treatment focuses on treating the underlying chronic venous insufficiency and its sequelae, such as lower extremity edema.[1]

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare infection of the fascia that leads to necrosis of the subcutaneous tissue. Its characteristic presentation includes fevers, erythema, edema, pain out of proportion to the exam, and crepitus. It qualifies as a surgical emergency and requires surgical debridement immediately. Imaging may be obtained to help confirm the diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis but should not delay surgical intervention. CT imaging revealing subcutaneous gas in the soft tissue is highly specific for necrotizing fasciitis.

Septic arthritis, or an infected joint, can involve any joint but typically involves the knee joint. Patients present with joint swelling, warmth, pain, and decreased mobility of the joint. Septic arthritis treatment is by joint aspiration and antibiotics directed at the most common pathogens.

Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is typically unilateral and presents with tenderness, erythema, warmth, and edema. It often affects the lower extremities. Patients commonly have the presence of risk factors for DVT, such as a history of immobility, active cancer, or a family history of venous thromboembolism. Deep vein thrombosis rarely manifests with fevers or leukocytosis, but they can be present. Ultrasound imaging is used to confirm the diagnosis.[4]

Prognosis

If the clinician promptly identifies cellulitis and initiates treatment with the correct antibiotic, patients can expect to notice an improvement in signs and symptoms within 48 hours. Annual recurrence of cellulitis occurs in about 8 to 20% of patients, with overall reoccurrence rates reaching as high as 49%.[7][1] Recurrence is preventable with prompt treatment of cuts or abrasions, proper hand hygiene, as well as effectively treating any underlying comorbidities. There is approximately an 18% failure rate with initial antibiotic treatment. Overall, cellulitis has a good prognosis.[11]

Complications

Without prompt diagnosis and treatment, cellulitis could lead to several complications. If the bacterial infection reaches the bloodstream, it could lead to bacteremia. Bacteremia is diagnosable by obtaining blood cultures in patients who exhibit systemic symptoms. The clinician should obtain identification and susceptibilities from the blood cultures and tailor antibiotics accordingly.[12] Failure to identify and treat bacteremia from cellulitis can lead to endocarditis, an infection of the inner lining (endocardium) of the heart.

Patients who have cellulitis along with two or more SIRS criteria (fever over 100.4 degrees F, tachypnea, tachycardia, or abnormal white cell count) get diagnosed with sepsis. If cellulitis moves from the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue to the bone, it can lead to osteomyelitis.

Cellulitis that leads to bacteremia, endocarditis, or osteomyelitis will require a longer duration of antibiotics and possibly surgery.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be informed to take prescribed antibiotics as indicated. Keep the area clean and dry. When possible, they should elevate the area above the level of their heart to reduced edema.

Cellulitis should start resolving within 24 to 48 hours after initiating antibiotics. Their healthcare provider may mark the area of erythema, and patients should return if they: notice the erythema beginning to spread or not responding to antibiotics, develop persistent fevers, begin developing significant bullae, or feel the pain worsens.[9]

Patients additionally should maintain good hand hygiene and adequately clean any future abrasions in their skin.[13]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Treatment and prevention of cellulitis requires an interprofessional approach with the patient, healthcare provider, pharmacist, and wound care nurses. The pharmacist ideally will have a board specialty in infectious disease to assist and work with the clinician on the best antibiotic selection. The majority of patients can have management as outpatients. Patients needing inpatient treatment with parenteral antibiotics, require collaboration with multiple members of the healthcare team: physician or advanced practice provider to correctly diagnosis the severity and type of cellulitis (purulent vs. nonpurulent), nurses to help demarcate the area of erythema and monitor for worsening or improving symptoms, and pharmacist to assist with parenteral dosing and monitoring of potentially renally toxic antibiotics such as vancomycin. The wound care nurse should educate the patient on maintaining good skincare, extremity elevation, and remain ambulatory - to prevent deep vein thrombosis. The pharmacist and nurse should both counsel the patient regarding medication compliance to ensure treatment success.

A collaborative interprofessional team approach is needed for patient education to ensure successful treatment as well as patient education to prevent recurrent infections.[14][15] Level V

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Raff AB, Kroshinsky D. Cellulitis: A Review. JAMA. 2016 Jul 19:316(3):325-37. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.8825. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27434444]

Cranendonk DR, Lavrijsen APM, Prins JM, Wiersinga WJ. Cellulitis: current insights into pathophysiology and clinical management. The Netherlands journal of medicine. 2017 Nov:75(9):366-378 [PubMed PMID: 29219814]

Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, J Rybak M, Talan DA, Chambers HF, Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of america for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 Feb 1:52(3):e18-55. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq146. Epub 2011 Jan 4 [PubMed PMID: 21208910]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQuirke M, Ayoub F, McCabe A, Boland F, Smith B, O'Sullivan R, Wakai A. Risk factors for nonpurulent leg cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The British journal of dermatology. 2017 Aug:177(2):382-394. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15186. Epub 2017 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27864837]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKaye KS, Petty LA, Shorr AF, Zilberberg MD. Current Epidemiology, Etiology, and Burden of Acute Skin Infections in the United States. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2019 Apr 8:68(Suppl 3):S193-S199. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30957165]

McNamara DR, Tleyjeh IM, Berbari EF, Lahr BD, Martinez JW, Mirzoyev SA, Baddour LM. Incidence of lower-extremity cellulitis: a population-based study in Olmsted county, Minnesota. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2007 Jul:82(7):817-21 [PubMed PMID: 17605961]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRichmond JM,Harris JE, Immunology and skin in health and disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2014 Dec 1 [PubMed PMID: 25452424]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2000 Jul:13(3):470-511 [PubMed PMID: 10885988]

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJ, Gorbach SL, Hirschmann JV, Kaplan SL, Montoya JG, Wade JC. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the infectious diseases society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2014 Jul 15:59(2):147-59. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu296. Epub 2014 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 24947530]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTorres J, Avalos N, Echols L, Mongelluzzo J, Rodriguez RM. Low yield of blood and wound cultures in patients with skin and soft-tissue infections. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2017 Aug:35(8):1159-1161. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.05.039. Epub 2017 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 28592371]

Obaitan I, Dwyer R, Lipworth AD, Kupper TS, Camargo CA Jr, Hooper DC, Murphy GF, Pallin DJ. Failure of antibiotics in cellulitis trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2016 Aug:34(8):1645-52. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.05.064. Epub 2016 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 27344098]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGunderson CG, Martinello RA. A systematic review of bacteremias in cellulitis and erysipelas. The Journal of infection. 2012 Feb:64(2):148-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2011.11.004. Epub 2011 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 22101078]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSwartz MN. Clinical practice. Cellulitis. The New England journal of medicine. 2004 Feb 26:350(9):904-12 [PubMed PMID: 14985488]

Singh M, Negi A, Zadeng Z, Verma R, Gupta P. Long-Term Ophthalmic Outcomes in Pediatric Orbital Cellulitis: A Prospective, Multidisciplinary Study From a Tertiary-Care Referral Institute. Journal of pediatric ophthalmology and strabismus. 2019 Sep 1:56(5):333-339. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20190807-01. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31545868]

Gibbons JA, Smith HL, Kumar SC, Duggins KJ, Bushman AM, Danielson JM, Yost WJ, Wadle JJ. Antimicrobial stewardship in the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections. American journal of infection control. 2017 Nov 1:45(11):1203-1207. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.05.013. Epub 2017 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 28732743]