Introduction

Celiac disease is an enteropathy of the small intestine. It is triggered by exposure to gluten in the diet of susceptible people. The susceptibility is genetically determined. The condition is chronic, and currently, the only treatment consists of permanent exclusion of gluten from the food intake.[1][2][3]

Patients with celiac disease can present with diarrhea and failure to thrive; some may be asymptomatic.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The symptoms of celiac disease are due to the damage of enterocytes in the small intestine. In the full-blown clinical picture, the typical features of the small intestine are chronic inflammation and villi atrophy. [4][5][4]

An individual has to have HLA dominant DQ2 or DQ8 genes. The disease is a result of the immune system reacting adversely to gluten, and one of the important proteins involved is an antibody to tissue transglutaminase. There are however other pathways proposed that contribute to the disease. The glycoprotein gliadin (present in gluten) has a direct toxic effect on enterocytes by the up-regulating production of IL-15.

Some studies indicate that gastrointestinal infections in early childhood are relevant to the development of celiac disease later in life. This is not surprising considering the organ affected, but it is likely that is also directly relevant to the fact that celiac disease is caused by a disorder of immune function.

IgA antibodies to smooth muscle endomysium and tissue transglutaminase are often used to make the diagnosis of celiac disease. However, only about 5% of patients with celiac disease have a deficiency of this immunoglobulin.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of celiac disease in the general population is about 0.5 % to 1%. Both true prevalence, as well as detection and diagnosis, have increased over the past 10 to 20 years. The incidence is greater among people with autoimmune disorders like type 1 diabetes. In first-degree relatives of people affected by celiac disease, the risk is 1 in 10.

Pathophysiology

A peptide derived from gluten called gliadin causes damage to the small intestine. There is local inflammation, and the process leads to the destruction of the small intestinal villi. This destruction, in turn, leads to the decreased functionality of the intestinal surface and malabsorption. The lack of nutrient absorption impacts directly on the digestive system but also indirectly on all the systems of the body. This impact results in generally poor health and is the reason why celiac disease can have signs and symptoms arising from almost any system of the body, not just the gastrointestinal system.[6]

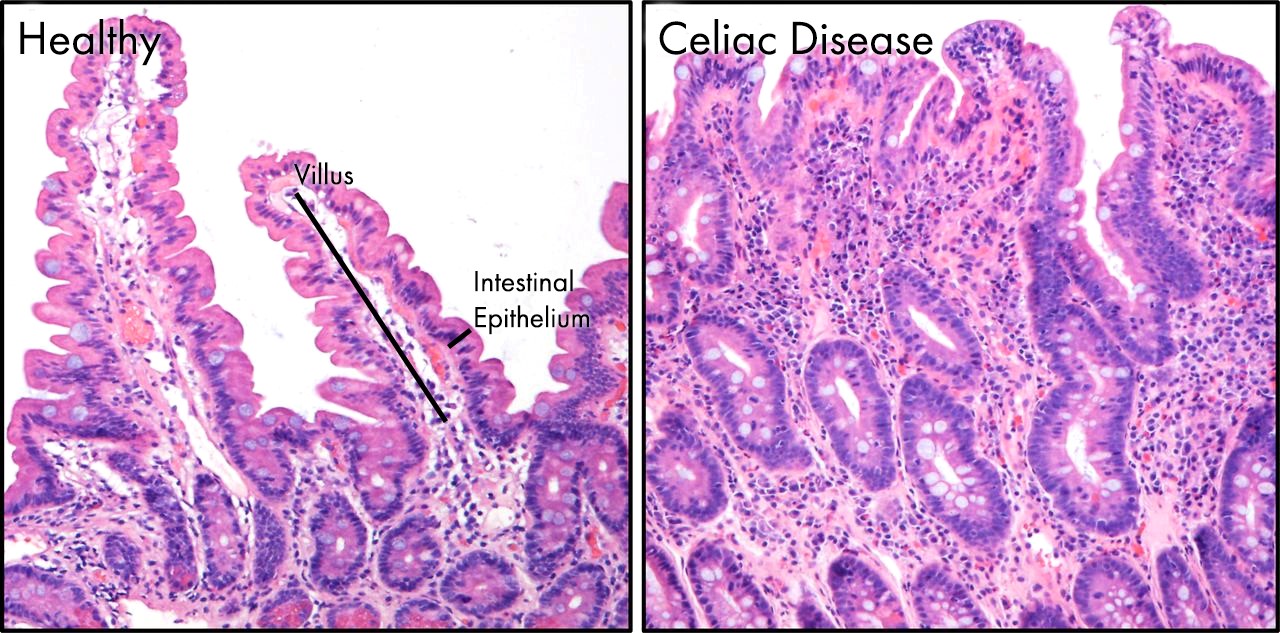

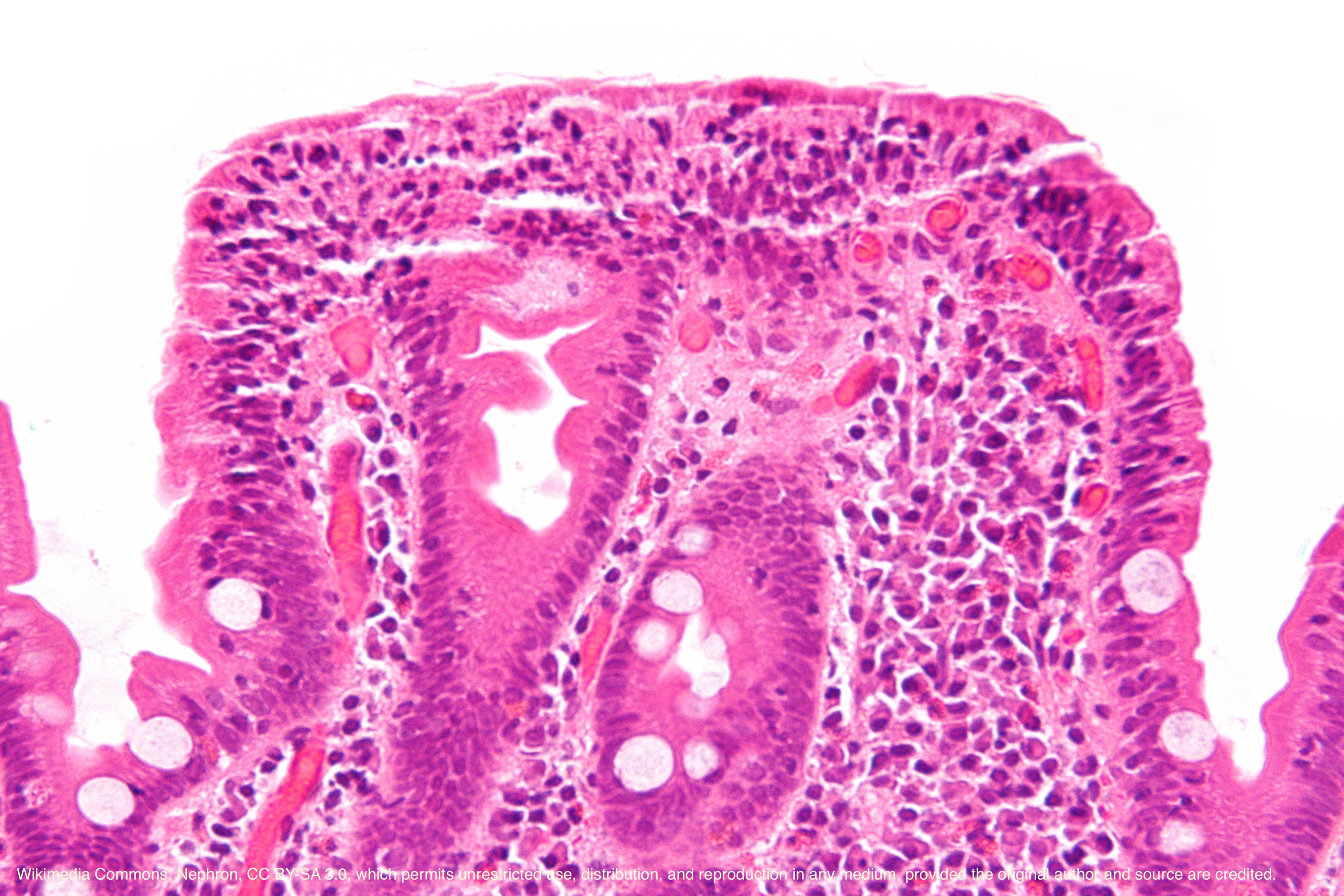

Histopathology

Celiac disease only involves the mucosa of the small bowel. The villi may be absent or atrophic and the crypt hyperplasia is present. An increased proliferation of lymphocytes and plasma cells is seen in the lamina propria.

Toxicokinetics

There has been long-standing doubt about the toxicity of oats for a patient with celiac disease. Recently, studies have shown that oats are not harmful, and any doubts were likely because it is commonly processed together with wheat and therefore, cross-contamination was very high.

History and Physical

The common symptoms are lethargy and diarrhea hence the name celiac sprue. Other gastrointestinal symptoms are abdominal distension, discomfort or pain, vomiting, and constipation. In childhood, failure to thrive is an important aspect of the history, while in adulthood the corresponding symptom would be unexplained weight loss. Symptoms from other than gastrointestinal systems include recurrent aphthous ulcers in the mouth, iron deficiency anemia, ataxia, chronic headaches, and delayed menarche. The incidence of some obstetric complications such as preterm labor, growth restriction, and stillbirth in women with the untreated celiac disease is higher.

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a skin condition caused by gluten intolerance, and just like the enteropathy it usually responds to the exclusion of gluten from the diet.

Extraintestinal symptoms are common and may include:

- Anemia due to defective absorption of vitamin B12, folate or iron

- Coagulopathy due to impaired absorption of vitamin K

- Osteoporosis

- Neurological symptoms like muscle weakness, paresthesias, seizures and ataxia

Evaluation

Diagnostic workup usually starts with serological tests. The two antibodies measured are anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay or ELISA measured numerically) and anti-endomysial antibodies that are usually reported as negative, weakly positive or positive. Traditionally, the next step and the gold standard for the diagnosis is duodenal mucosal biopsy; in celiac disease, this shows villous atrophy. It is important that these tests be performed while the patient is on a regular, gluten-containing diet.[7][8]

Another useful test is for human leukocyte antigen (HLA). Specific HLA genotypes have been strongly associated with celiac disease. HLA testing can be used in the diagnostic process. For example, Joint BSPGHAN and Celiac UK guidelines published in 2013 indicates that positive serological tests with positive HLA typing in the presence of typical symptoms can be accepted as confirmative of diagnosis without a need for biopsy.

Laboratory studies:

- Both type 1 diabetics and down syndrome have a high incidence of celiac disease; so appropriate workup is required

- Electrolytes may reveal hypocalcemia, hypokalemia, metabolic acidosis

- Anemia due to deficiency of folate, iron or Vit B12

- Prothrombin time may be prolonged

- Stool are greasy and have a rancid odor

Radiology

Small bowel follow-through may reveal obliteration of intestinal mucosa, bowel dilatation and flocculation of the barium.

Upper endoscopy is often used to confirm the diagnosis

Treatment / Management

It is recommended that all people diagnosed with celiac disease follow a strict gluten-free diet. This adherence is best done under the supervision of specialists, including a dietician. In general, symptoms improve on the gluten-free diet within days to weeks. Unresponsive patients need further review of the diagnosis but also an assessment of compliance with the diet. Serology testing can assess compliance. Non-compliance can be unintentional in an individual who may be still ingesting gluten without realizing it.[9][10]

Other tests include looking at the impact of malabsorption (due to celiac disease). The following can be monitored: full blood count, iron stores, folate, ferritin, levels of vitamin D and other fat-soluble vitamins, and bone mineral density.

Management of patients with positive serology but no abnormal findings on biopsy on duodenal biopsy is controversial. There are many situations when the diagnosis is not clear-cut. Some patients experience relevant symptoms in spite of no identified changes on small gut biopsy. There is also seronegative celiac disease. This term describes the reverse situation when in spite of typical symptoms there is no serological evidence of the disease, but there is significant villous atrophy of duodenal biopsy.

Currently, the only recommended treatment for celiac disease is the gluten-free diet. This makes a significant impact on the lives of people affected and can be challenging to maintain. There is continuous work on possible non-dietary therapies that enable people with celiac disease to tolerate gluten. One of the main focuses of the research in this area is immune modulators. Other approaches, like immunizations or ingesting substances that would change the toxicity of gluten are also being explored. However, none have reached the stage of being recommended or approved for such therapy.

Corticosteroids only benefit a small percentage of patients with celiac disease.

Differential Diagnosis

- Bacterial gastroenteritis

- Crohn disease

- Giardia

- Irritable Bowel syndrome

- Malabsorption

- Viral gastroenteritis

Prognosis

The prognosis for patients with the correct diagnosis and treatment is good. Unfortunately, compliance with a gluten-free diet is very difficult and relapses are common. Some patients do not respond to a gluten-free diet or corticosteroids; they have a poor quality of life.

Complications

There is a risk of lymphomas and small bowel adenocarcinomas of the small bowel in the long run.

Pregnant women may have a miscarriage and/or have an infant with congenital birth defects

Short stature and failure to thrive can occur in children

Failure to absorb the nutrients can lead to the following:

- Osteopenia

- Bleeding diathesis

- Stunted growth

- Anemia

- Lack of exercise endurance

- Seizures

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Once the diagnosis of celiac disease is made, patents need regular follow up to ensure that they are compliant with a gluten-free diet and not developing any complications.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient should remain compliant with a gluten-free diet

Pearls and Other Issues

The untreated coeliac disease leads to chronic ill health and complications. Secondary lactose intolerance is common. There is increased the risk of osteoporosis, epilepsy, infections and bowel cancer and jejunal lymphoma. Lack of calcium leads to problems with dentition.

Because celiac disease is an autoimmune disease, many clinicians recommend that all patients with celiac disease should also be screened for type 1 diabetes and thyroid function problems. This screening is recommended because similar autoimmune disturbances are at the root of these disorders and therefore, there is increased the risk of these disorders in people who share the common genetic background.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The number of cases of celiac disease has gone up in the last three decades. In fact, the disease is initially often mistaken for irritable bowel syndrome, and the diagnosis is delayed for months or years. Celiac disease can have significant complications if it is not treated and hence, an interprofessional team approach to diagnosis and treatment is necessary. Most patients initially present to the nurse practitioner, pediatrician or primary care provider with complaints of diarrhea and abdominal pain.

If the disorder is suspected a gastroenterologist should be consulted. Once the disease is confirmed, patients are generally managed as outpatients. Nurses play a vital role in the monitoring of these patients for complications and compliance with the diet. A dietary consult is highly recommended as these patients need to know the importance of a gluten-free diet.

Further, children will need to be monitored for stunted growth and failure to thrive.[11][12] (Level V)

Several national guidelines have recommended an interprofessional approach to celiac disease as it can involve many organs in the body. New evidence reveals that these patients may be prone to a high rate of fractures and hence, bone scanning should be performed.

Comprehensive nutritional management is required with an interprofessional approach to treatment. The nurse should monitor patients for refractoriness to treatment because these patients may require corticosteroids. In addition, all healthcare workers who look after celiac patients should be aware that the disorder can cause lymphomas and adenocarcinomas of the intestine at some point. Further, celiac disease is also associated with psychiatric illness, depression, and infertility.[13] [Level 5]

Outcomes

The prognosis for patients who are diagnosed early and remain compliant with their gluten-free diet is excellent. However, there are some patients who do not respond well to a gluten-free diet, and they may require steroids. The prognosis for these patients is guarded.[14][15]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Yu XB, Uhde M, Green PH, Alaedini A. Autoantibodies in the Extraintestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease. Nutrients. 2018 Aug 20:10(8):. doi: 10.3390/nu10081123. Epub 2018 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 30127251]

Clark R, Johnson R. Malabsorption Syndromes. The Nursing clinics of North America. 2018 Sep:53(3):361-374. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2018.05.001. Epub 2018 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 30100002]

Sharma P, Baloda V, Gahlot GP, Singh A, Mehta R, Vishnubathla S, Kapoor K, Ahuja V, Gupta SD, Makharia GK, Das P. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiation between celiac disease and tropical sprue: A systematic review. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2019 Jan:34(1):74-83. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14403. Epub 2018 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 30069926]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSavvateeva LV,Erdes SI,Antishin AS,Zamyatnin AA Jr, Current Paediatric Coeliac Disease Screening Strategies and Relevance of Questionnaire Survey. International archives of allergy and immunology. 2018 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 30056445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcAllister BP, Williams E, Clarke K. A Comprehensive Review of Celiac Disease/Gluten-Sensitive Enteropathies. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2019 Oct:57(2):226-243. doi: 10.1007/s12016-018-8691-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29858750]

do Vale RR, Conci NDS, Santana AP, Pereira MB, Menezes NYH, Takayasu V, Laborda LS, da Silva ASF. Celiac Crisis: an unusual presentation of gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Autopsy & case reports. 2018 Jul-Sep:8(3):e2018027. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.027. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30101133]

Glissen Brown JR, Singh P. Coeliac disease. Paediatrics and international child health. 2019 Feb:39(1):23-31. doi: 10.1080/20469047.2018.1504431. Epub 2018 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 30099930]

Bai JC, Ciacci C. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines: Celiac Disease February 2017. Journal of clinical gastroenterology. 2017 Oct:51(9):755-768. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000919. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28877080]

Walker MM, Ludvigsson JF, Sanders DS. Coeliac disease: review of diagnosis and management. The Medical journal of Australia. 2017 Aug 21:207(4):173-178 [PubMed PMID: 28814219]

Werkstetter KJ, Korponay-Szabó IR, Popp A, Villanacci V, Salemme M, Heilig G, Lillevang ST, Mearin ML, Ribes-Koninckx C, Thomas A, Troncone R, Filipiak B, Mäki M, Gyimesi J, Najafi M, Dolinšek J, Dydensborg Sander S, Auricchio R, Papadopoulou A, Vécsei A, Szitanyi P, Donat E, Nenna R, Alliet P, Penagini F, Garnier-Lengliné H, Castillejo G, Kurppa K, Shamir R, Hauer AC, Smets F, Corujeira S, van Winckel M, Buderus S, Chong S, Husby S, Koletzko S, ProCeDE study group. Accuracy in Diagnosis of Celiac Disease Without Biopsies in Clinical Practice. Gastroenterology. 2017 Oct:153(4):924-935. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.002. Epub 2017 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 28624578]

Paul SP,Harries SL,Basude D, Barriers to implementing the revised ESPGHAN guidelines for coeliac disease in children: a cross-sectional survey of coeliac screen reporting in laboratories in England. Archives of disease in childhood. 2017 Oct [PubMed PMID: 28483757]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLaurikka P, Nurminen S, Kivelä L, Kurppa K. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Celiac Disease: Early Detection for Better Long-Term Outcomes. Nutrients. 2018 Aug 3:10(8):. doi: 10.3390/nu10081015. Epub 2018 Aug 3 [PubMed PMID: 30081502]

Pekki H, Kaukinen K, Ilus T, Mäki M, Huhtala H, Laurila K, Kurppa K. Long-term follow-up in adults with coeliac disease: Predictors and effect on health outcomes. Digestive and liver disease : official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2018 Nov:50(11):1189-1194. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.05.015. Epub 2018 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 30025706]

Haridy J, Lewis D, Newnham ED. Investigational drug therapies for coeliac disease - where to from here? Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2018 Mar:27(3):225-233. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2018.1438407. Epub 2018 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 29411655]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence