Introduction

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is an aggressive non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma. The disease is associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and chromosomal translocations that cause the overexpression of oncogene C-MYC.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) classifies BL into three clinical groups: endemic, sporadic and immunodeficiency-related. The endemic form is linked to malaria and EBV. The immunodeficiency-related variant is associated with HIV and to a lesser extent, organ transplantation. With intense chemotherapy treatment disease prognosis is excellent in children but poor in adults.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Burkitt lymphoma (BL) is associated with Epstein Barr virus (EBV). The exact mechanism underlying EBV and B-cell malignancy remains unclear. EBNA1 protein is an EBV latent protein expressed in endemic BL.[1] EBNA2 gene deletion leads to the expression of EBNA3 genes (i.e., EBNA3A-C). Tumor cells derived from these cell lines are resistant to apoptosis; thus, EBNA2 might confer a survival advantage for the neoplastic cells. Burkitt lymphoma is endemic to areas where malaria is holoendemic, such as Brazil, Papua New Guinea, and equatorial Africa. Studies showed a direct correlation between endemic BL and increased Plasmodium falciparum antibody titers. Immunodeficiency-associated BL is linked to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Counterintuitively, the incidence of lymphoma is higher when the patient has a CD4 count greater than 200 and no opportunistic infection. It is not clear how HIV affects the risk of endemic BL.

Epidemiology

Burkitt lymphoma accounts for approximately 1% to 5% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas.[2] BL is more common in Caucasians than persons of African or Asian descent. As with most types of lymphoma, BL is more prevalent in males with a 3-4:1 male-to-female ratio.[3] The distribution of endemic cases of BL in Africa and Papua New Guinea corresponds to areas where malaria and Epstein Barr virus are prevalent. In children younger than 18 years of age, the incidence is approximately 3 to 6 cases per 100,000 children annually. The average age of diagnosis is 6 years. The sporadic form is localized to North America and Europe with a median age of diagnosis of 45. Sporadic BL has an annual estimated incidence of 4 per 1 million children less than 16 years of age whereas the incidence is 2.5 per 1 million in adults. The average age of diagnosis in pediatric patients is 3 to 12 years of age. The immunodeficiency-associated variant has an incidence of 22 per 100,000 persons in the United States.

Pathophysiology

The MYC family is composed of regulator genes and oncogenes that encode transcription factors that regulate the cell cycle. Translocations of the c-MYC gene on chromosome 8 is the hallmark of BL, occurring in approximately 95% of cases. The t(8;14)(q24;q32) is the most common translocation in BL, occurring in 70% to 80%.[1] The MYC oncogene is relocated to be juxtaposed to the promoter sequence of the immunoglobulin IgG heavy chain (IgH) gene leading to constitutive activation of MYC. Other translocations include t(2;8)(p12; q24) and t(8;22)(q24; q11). The collocation of the MYC oncogene to the heavy chain (14q32), kappa light chain (2p12) or lambda light chain (22q11) of the immunoglobulin gene results in the dysregulation of the MYC. The presence of an MYC rearrangement is not specific for BL.[4]

In addition to the characteristic translocation of c-MYC, many gene mutations have been identified, including truncating mutations of ARID1A, amplification of MCL1, truncating alterations of PTEN, NOTCH, and ATM; amplifications of RAF1, MDM2, KRAS, IKBKE, deletion of CDKN2A, and CCND3 activating mutations.[3][5] In normal B-cells, MYC overexpression causes apoptosis via a p53-dependent pathway. In the neoplastic cells of BL, it is not uncommon for tumor suppressor gene TP53 to be mutated.

In endemic BL, EBV latent proteins prevent apoptosis in B-cells containing the C-MYC translocation via EBNA1 protein, BHRF1 protein, EBER transcripts, vIL-10, BZLF1, and LMP1. The prevention of apoptosis likely gives rise to the malignant clone of B-cells. EBV is implicated in promoting genomic instability, telomere dysfunction, and DNA damage. Plasmodium falciparum prompts the reactivation of latent EBV. Additionally, P. falciparum can activate toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) which induces immunoglobulin-MYC translocations. Cytidine deaminase allows for B-cells to switch from IgM expression to the expression of other immunoglobulin subtypes. Aberrant expression of cytidine deaminase is correlated with C-MYC translocation. The enzyme is not detected in HIV-positive patients that do not have Burkitt lymphoma.

Histopathology

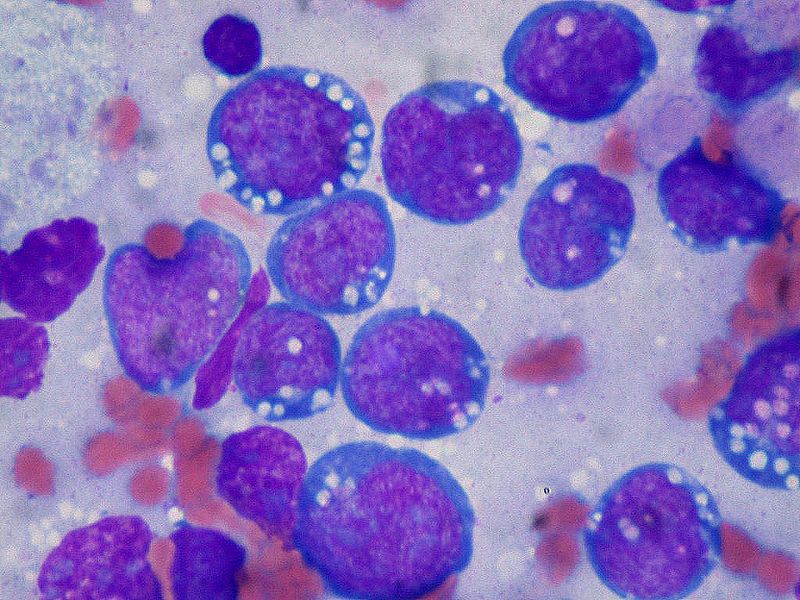

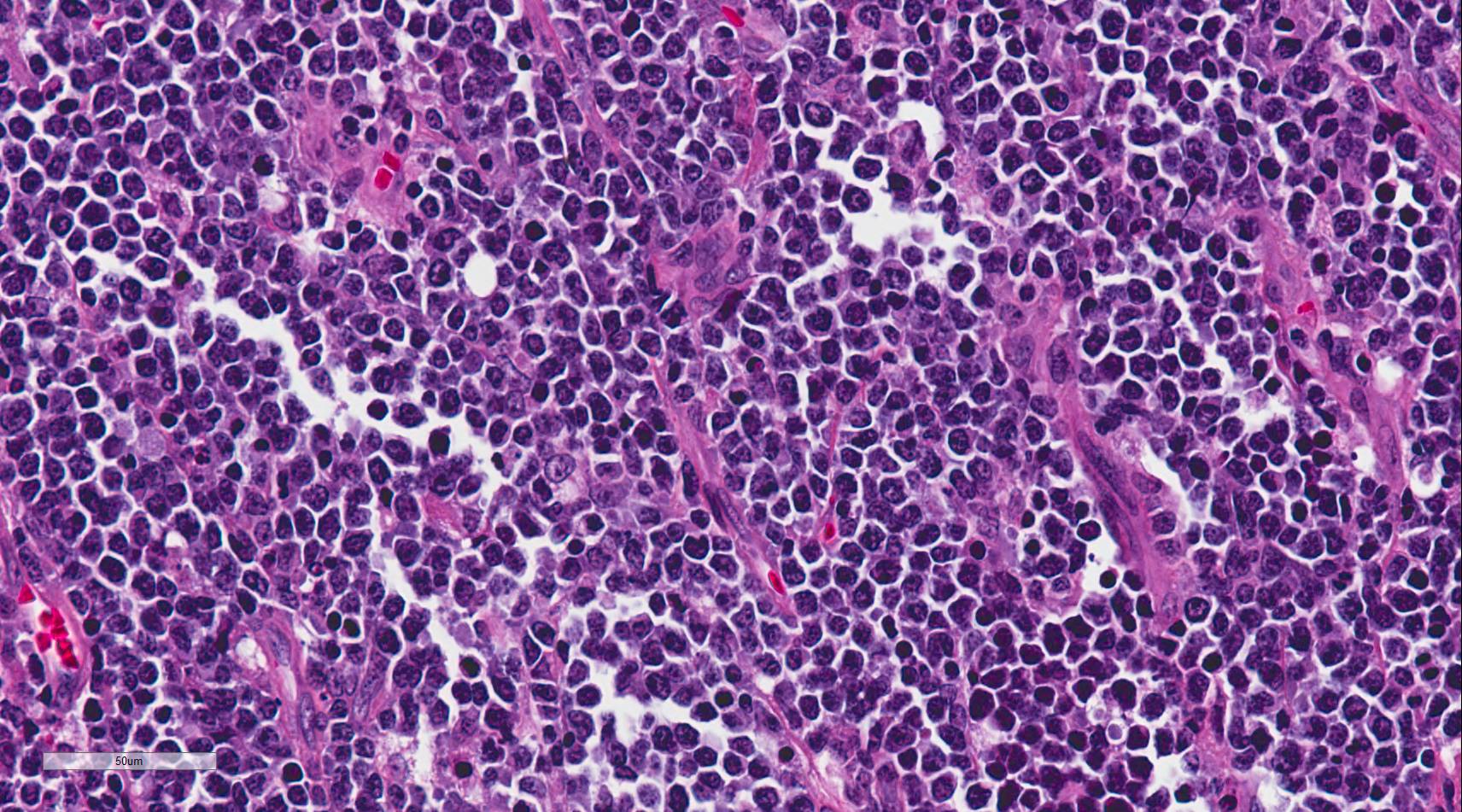

Burkitt lymphoma is an aggressive B-cell lymphoma comprising a monomorphic population of intermediate-sized mature lymphocytes. The cells contain round nuclei with lacy chromatin and may have one or more small nucleoli. The cells characteristically have basophilic cytoplasm with prominent vacuoles.[6] On hematoxylin-eosin (HandE) stained sections, the cells have distinct cytoplasmic borders giving them a molded appearance. Morphologic variants are plasmacytoid or pleomorphic. The neoplastic cells are highly proliferative, which is reflected in the increased number of mitotic figures. Increased cell turnover is countered by increased apoptosis. In tissue, this results in a "starry sky" appearance due to tingible-body macrophages containing cellular debris.[1]

Immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics play a significant role in the diagnosis and management of Burkitt lymphoma. The malignant B-cells express surface IgM. The cells are positive for B-cell markers including CD19, CD20, CD79a, and PAX5. They are positive for germinal center markers CD10 and bcl-6 but are negative for bcl-2. The neoplastic cells do not express T-cell markers and do not express immature markers TdT or CD34. Rapid cell turnover is reflected by high Ki67 positivity nearing 100%, which is a very helpful diagnostic clue.

History and Physical

Patients often present with a rapidly growing mass, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), and increased uric acid levels because of the tumor’s rapid doubling time. The primary site of sporadic BL is typically the abdomen, but the head and neck may be affected as well.[1] Patients present with abdominal pain secondary to ileocecal disease, abdominal distention, nausea, vomiting, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Adult patients are more likely to present with constitutional symptoms (i.e., fever, weight loss, night sweats). Infrequently, patients have jaw or bone marrow involvement. BL rarely involves the mediastinum, central nervous system, testes, skin, thyroid gland, and breast. Endemic BL characteristically presents with an enlarging jaw lesion, periorbital swelling, or genitourinary involvement. Jaw involvement is seen predominantly in children. Malnourishment is common at disease presentation. If the patient has bone marrow involvement consisting of greater than 25% of cellularity, then the disease is classified as Burkitt leukemia. A purely leukemic presentation is rare.

Evaluation

Adequate tissue is paramount to the diagnosis. Fine-needle aspiration might not provide enough tissue for the diagnosis; thus, excisional biopsy is preferred. Superficial lymph node or pleural fluid may be sampled for diagnosis. In developed countries, BL is suspected by microscopy or flow cytometry and confirmed by immunohistochemistry and cytogenetics. In areas without access to confirmatory testing, the diagnosis of Burkitt may be made with by fine-needle aspiration and clinical correlation.

After a tissue diagnosis is made, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy, as well as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) evaluation ought to be performed to assess the extent of involvement. Computerized tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are performed initially. Whole body PET/CT scans should be done but should not delay therapy. Required lab tests include complete blood count (CBC) with differential, ESR, complete metabolic panel (CMP), PT, PTT, serum lactate dehydrogenase, uric acid, hepatitis B serology, pregnancy testing in women, and HIV testing.[1] In areas with limited resources, ultrasonography may aid in staging.[7]

Treatment / Management

In developed countries, the overall cure rate for sporadic Burkitt lymphoma approaches 90% in pediatric and young adult populations. Treatment is stratified based on patient age and stage. In pediatric patients with complete surgical resection of disease, it is recommended that patients receive two cycles of chemotherapy of moderate-intensity (i.e. cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin). In pediatric patients with stage I and II disease, overall survival is greater than 98%.[1] For children with residual or stage III disease, it is advised that the patient receives a minimum of four cycles of dose-intensive chemotherapy (i.e. two cycles of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate). After which the patient receives two cycles of cytarabine and high-dose methotrexate. Intrathecal therapy is administered concurrently with chemotherapy. Lastly, in pediatric patients with CNS or bone marrow involvement, it is recommended that patients receive up to eight cycles of dose-intensive chemotherapy (i.e. two cycles of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone, doxorubicin, and high-dose methotrexate) plus two courses of cytarabine and etoposide, in addition to four courses of maintenance chemotherapy (i.e. vincristine, prednisolone, high-dose methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, cytarabine, and etoposide). Like residual or stage III disease, intrathecal therapy is administered concomitantly with chemotherapy.(B2)

Standard chemotherapy regimens, such as cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP) are inadequate in treating adult Burkitt lymphoma. Current recommendations are offered by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and include multiagent regimens with CNS prophylaxis:

- R-hyper-CVAD[8]

- CODOX-M/IVACA[9] with or without rituximab[10]

- dose-adjusted EPOCH with rituximab[11] (B2)

Immunotherapy has a role in treatment. Rituximab (anti-CD20) should be a component of all treatment regimens as it is correlated with a positive prognosis. Newer anti-CD20 agents, ofatumumab and obinutuzumab, are under investigation. Blinatumomab, an Anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody, and inotuzumab, an anti-CD22 monoclonal antibody, are under investigation. Experimental drugs to inhibit the growth of BL B-cells by inducing apoptosis include histone acetylase inhibitors (i.e., rapamycin, valproic acid, tubacin) and mTOR inhibitors (i.e., temsirolimus). Anti-PD1 agents prevent tumor cells from evading the immune system via the PD1 pathway. Therapies inhibiting the MYC oncogene are under investigation.[3]

Highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HARRT) has allowed for the management of immunodeficiency-related Burkitt lymphoma using high dose chemotherapy in patients with HIV. In this patient population, it is advised that less toxic chemotherapy is used because of the susceptibility to organ failure and infection.[6]

In patients with relapsing disease, the prognosis is typically poor, and treatment will depend on the specific clinical scenario. However, the development of more effective chemotherapy drugs (i.e., ifosfamide, carboplatin, etoposide) is improving patient outcomes. Salvage regimens may include R-IVAC, R-GDP, R-ICE, DHAP.[3] Autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant may be considered.[12] In elderly patients who cannot endure intense chemotherapy, treatment is often palliative.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of BL primarily includes other CD10 positive B-cell lymphomas: diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), high-grade follicular lymphoma, and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma (B-ALL). Both DLBCL and high-grade follicular lymphoma typically have larger cells with more pleomorphism than is expected with BL. BCL2 positivity and a Ki67 proliferation index less than 90% favor a diagnosis other than BL. Finding an MYC translocation is not diagnostic of BL; approximately 10% of DLBCL have an MYC translocation.[6] B-ALL may resemble BL in size, but it typically has finer chromatin. By immunohistochemistry or flow cytometry, B-ALL will often express markers of immaturity such as CD34 and/or TdT.

There are also some uncommonly encountered entities to consider. Cases with BL-type morphology that lack an MYC translocation should be examined for abnormalities of chromosome 11q for the diagnosis of "Burkitt-like lymphoma with 11q aberration."[13] The prognosis for this recently described entity appears similar to BL.

Treatment Planning

Treatment should begin within 48 hours of diagnosis without being delayed for further studies.

Toxicity and Adverse Effect Management

Tumor lysis syndrome, which is the cytolysis of tumor cells causing hyperuricemia, hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, and hypocalcemia.[3] Calcium can precipitate in the kidneys, causing acute kidney injury (AKI). The flux of calcium, phosphate, and potassium is associated with cardiac arrhythmias, CNS toxicity, and death. Because TLS can occur before treatment is initiated, prophylaxis should be started promptly. Tumor lysis syndrome is more likely to occur in male patients, as well as patients with a history of renal disease, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) or uric acid levels, or splenomegaly. Rigorous hydration before and after chemotherapy treatment, allopurinol and rasburicase have improved outcomes. Hemodialysis is advised if the patient develops severe kidney injury.

Chemotherapy is associated with significant side effects, namely hematologic toxicity and severe infection risk. In underdeveloped nations, treatment must be catered to account for socioeconomic factors.[1] Supportive care is essential, particularly the prevention of tumor lysis syndrome, fever management, and nutrition supplementation. Because of the high cost, lack of access to medical care, and health illiteracy many patients do not complete treatment. In patients with endemic BL, 1-year event-free survival is a gauge of long-term survival (risk of relapse is less than or equal to 5% after 1 year).

Staging

The St. Jude staging system is routinely used for pediatric patients, whereas the Ann Arbor system and Murphy staging system are commonly used for adults. The Ann Arbor system accounts for the patient’s symptoms. The Murphy staging system is used because of its emphasis on extranodal disease, and for distinguishing bone marrow involvement from central nervous system disease. Because of the aggressive nature of the disease in adult patients, staging should be performed using bone marrow, and lumbar puncture samples and treatment started immediately after confirmation of diagnosis.

St. Jude/Murphy Staging System (Children)

- Stage I: A single tumor (extranodal) or a single anatomical area (nodal), excluding mediastinum or abdomen or a tumor (extranodal) with regional node involvement, on the same side of the diaphragm.

- Stage II: A single tumour (extranodal) with regional node involvement, lymph node involvement on same side of the diaphragm (two or more nodal areas or two single extranodal tumours, with or without regional node involvement), or a primary gastrointestinal tract tumour (usually ileocecal) with or without associated mesenteric node involvement, grossly completely resected.

- Stage III: On both sides of the diaphragm (two or more nodal areas or two single extranodal tumours), all primary intrathoracic tumours (e.g., mediastinal or pleural thymic), all extensive primary intraabdominal disease; unresectable abdominal disease, even if only in one area, or all primary paraspinal or epidural tumours, irrespective of other sites.

- Stage IV: Any of the above with initial CNS or bone marrow involvement (only if less than 25% of the marrow is composed of Burkitt cells).[1]

Murphy System (Adult)

- Stage I: Single nodal or extranodal site excluding the mediastinum or abdomen.

- Stage II: Two or more nodal areas on one side of the diaphragm.

- Stage IIR: Completely resectable abdominal disease

- Stage III: Two or more nodal areas on opposite sides of the diaphragm, or a primary intrathoracic tumor, paraspinal or epidural tumors, extensive intra-abdominal disease

- Stage IIIA: Completely non-resectable abdominal disease

- Stage IIIB: Widespread multiorgan intra-abdominal disease

- Stage IV: Central nervous system or bone marrow involvement

Favorable: Stage I or IIR[6]

Ann Arbor System (Adult)

- Stage 1: Single nodal or extranodal site

- Stage II: Two or more nodal areas on one side of the diaphragm, or localized involvement of an extra-lymphatic site and one or more sites on the same side of the diaphragm (IIE)

- Stage III: Two or more nodal areas on opposite sides of the diaphragm which may include/ involvement of the spleen (IIIs), or localized involvement of an extranodal site (IIIE)

- Stage IV: Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extra-lymphatic sites, or two single extranodal tumors on opposite sides of the diaphragm

Favorable: Stage I, II, III[6]

Prognosis

Prognosis is dependent on clinical and histopathologic staging, particularly the extent of disease. In general, younger patients have a better prognosis. It is possible that pediatric patients are better able to tolerate intense chemotherapy.

Poor response to cyclophosphamide, prednisolone, and vincristine are poor prognostic indicators, as well as detection of CNS disease at presentation. Elevated lactose dehydrogenase concentrations (twice the upper limit of normal values) is associated with poor outcomes. The finding of some additional cytogenetic findings beyond the MYC translocation, including deletion of 13q, a gain of 7q, or complex cytogenetics may portend a worse prognosis.[3] Double hit mutations in ID3, CCND3, and mutations in 18q21 CN-LOH indicate a poor response to therapy and poor prognosis. Malnourishment, particularly in low-income countries, is associated with neutropenia secondary to chemotherapy. In immunodeficiency-related BL, low CD4 count is a poor prognostic indicator. When BL relapses within 6 months of treatment completion, the prognosis is poor because of the limited availability of new drugs for treatment as most were exhausted during initial therapy. Conversely, in developing nations where treatment is less aggressive, a greater number of children can be treated after relapse.

In developing countries, the stage of the disease and abdominal ultrasound are used to determine prognosis. Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) scans are utilized to evaluate for residual or recurrent disease. The prognostic significance of early PET scans or CT scans to assess disease is an area of investigation. Research is being conducted to elucidate whether minimal residual disease (MRD) is a risk factor for worse prognosis in Burkitt lymphoma. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be used to assess MRD by detecting MYC/IgH fusion.[14]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis, evaluation, and management of Burkitt's lymphoma require a team of healthcare providers comprising at a minimum a pathologist, hematologist, oncologist, pharmacist, and radiologist. When there is suspicion for BL, communication between team members is critical to expedite diagnosis with judicious use of ancillary tests such as FISH for MYC translocations.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Molyneux EM, Rochford R, Griffin B, Newton R, Jackson G, Menon G, Harrison CJ, Israels T, Bailey S. Burkitt's lymphoma. Lancet (London, England). 2012 Mar 31:379(9822):1234-44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61177-X. Epub 2012 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 22333947]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLinch DC. Burkitt lymphoma in adults. British journal of haematology. 2012 Mar:156(6):693-703. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08877.x. Epub 2011 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 21923642]

Dozzo M, Carobolante F, Donisi PM, Scattolin A, Maino E, Sancetta R, Viero P, Bassan R. Burkitt lymphoma in adolescents and young adults: management challenges. Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics. 2017:8():11-29. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S94170. Epub 2016 Dec 23 [PubMed PMID: 28096698]

Haberl S, Haferlach T, Stengel A, Jeromin S, Kern W, Haferlach C. MYC rearranged B-cell neoplasms: Impact of genetics on classification. Cancer genetics. 2016 Oct:209(10):431-439. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.08.007. Epub 2016 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 27810071]

Grande BM, Gerhard DS, Jiang A, Griner NB, Abramson JS, Alexander TB, Allen H, Ayers LW, Bethony JM, Bhatia K, Bowen J, Casper C, Choi JK, Culibrk L, Davidsen TM, Dyer MA, Gastier-Foster JM, Gesuwan P, Greiner TC, Gross TG, Hanf B, Harris NL, He Y, Irvin JD, Jaffe ES, Jones SJM, Kerchan P, Knoetze N, Leal FE, Lichtenberg TM, Ma Y, Martin JP, Martin MR, Mbulaiteye SM, Mullighan CG, Mungall AJ, Namirembe C, Novik K, Noy A, Ogwang MD, Omoding A, Orem J, Reynolds SJ, Rushton CK, Sandlund JT, Schmitz R, Taylor C, Wilson WH, Wright GW, Zhao EY, Marra MA, Morin RD, Staudt LM. Genome-wide discovery of somatic coding and noncoding mutations in pediatric endemic and sporadic Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2019 Mar 21:133(12):1313-1324. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-09-871418. Epub 2019 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 30617194]

Sandlund JT. Burkitt lymphoma: staging and response evaluation. British journal of haematology. 2012 Mar:156(6):761-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09026.x. Epub 2012 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 22296338]

Marjerrison S, Fernandez CV, Price VE, Njume E, Hesseling P. The use of ultrasound in endemic Burkitt lymphoma in Cameroon. Pediatric blood & cancer. 2012 Mar:58(3):352-5. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23050. Epub 2011 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 21370431]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThomas DA, Faderl S, O'Brien S, Bueso-Ramos C, Cortes J, Garcia-Manero G, Giles FJ, Verstovsek S, Wierda WG, Pierce SA, Shan J, Brandt M, Hagemeister FB, Keating MJ, Cabanillas F, Kantarjian H. Chemoimmunotherapy with hyper-CVAD plus rituximab for the treatment of adult Burkitt and Burkitt-type lymphoma or acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2006 Apr 1:106(7):1569-80 [PubMed PMID: 16502413]

Mead GM, Sydes MR, Walewski J, Grigg A, Hatton CS, Pescosta N, Guarnaccia C, Lewis MS, McKendrick J, Stenning SP, Wright D, UKLG LY06 collaborators. An international evaluation of CODOX-M and CODOX-M alternating with IVAC in adult Burkitt's lymphoma: results of United Kingdom Lymphoma Group LY06 study. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2002 Aug:13(8):1264-74 [PubMed PMID: 12181251]

Barnes JA, Lacasce AS, Feng Y, Toomey CE, Neuberg D, Michaelson JS, Hochberg EP, Abramson JS. Evaluation of the addition of rituximab to CODOX-M/IVAC for Burkitt's lymphoma: a retrospective analysis. Annals of oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology. 2011 Aug:22(8):1859-64. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq677. Epub 2011 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 21339382]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Shovlin M, Steinberg SM, Cole D, Grant C, Widemann B, Staudt LM, Jaffe ES, Little RF, Wilson WH. Low-intensity therapy in adults with Burkitt's lymphoma. The New England journal of medicine. 2013 Nov 14:369(20):1915-25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308392. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24224624]

Gross TG, Hale GA, He W, Camitta BM, Sanders JE, Cairo MS, Hayashi RJ, Termuhlen AM, Zhang MJ, Davies SM, Eapen M. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for refractory or recurrent non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children and adolescents. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation : journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010 Feb:16(2):223-30. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.09.021. Epub 2009 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 19800015]

Salaverria I, Martin-Guerrero I, Wagener R, Kreuz M, Kohler CW, Richter J, Pienkowska-Grela B, Adam P, Burkhardt B, Claviez A, Damm-Welk C, Drexler HG, Hummel M, Jaffe ES, Küppers R, Lefebvre C, Lisfeld J, Löffler M, Macleod RA, Nagel I, Oschlies I, Rosolowski M, Russell RB, Rymkiewicz G, Schindler D, Schlesner M, Scholtysik R, Schwaenen C, Spang R, Szczepanowski M, Trümper L, Vater I, Wessendorf S, Klapper W, Siebert R, Molecular Mechanisms in Malignant Lymphoma Network Project, Berlin-Frankfurt-Münster Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Group. A recurrent 11q aberration pattern characterizes a subset of MYC-negative high-grade B-cell lymphomas resembling Burkitt lymphoma. Blood. 2014 Feb 20:123(8):1187-98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-507996. Epub 2014 Jan 7 [PubMed PMID: 24398325]

Shiramizu B, Goldman S, Smith L, Agsalda-Garcia M, Galardy P, Perkins SL, Frazer JK, Sanger W, Anderson JR, Gross TG, Weinstein H, Harrison L, Barth MJ, Mussolin L, Cairo MS. Impact of persistent minimal residual disease post-consolidation therapy in children and adolescents with advanced Burkitt leukaemia: a Children's Oncology Group Pilot Study Report. British journal of haematology. 2015 Aug:170(3):367-71. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13443. Epub 2015 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 25858645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence