Introduction

Bell palsy is the most common peripheral paralysis of the seventh cranial nerve with an onset that is rapid and unilateral. The diagnosis is one of exclusion and is most often made on physical exam.

The facial nerve has both an intracranial, intratemporal, and extratemporal course as its branches. The facial nerve has a motor and parasympathetic function as well as taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. This nerve also controls salivary and lacrimal glands. The motor function of the peripheral facial nerve controls the upper and lower facial muscles. As a result, the diagnosis of Bell palsy requires special attention to forehead muscle strength. If forehead strength is preserved, a central cause of weakness should be considered. Although the utility of antivirals has been called into question, treatment is medical with most sources recommending a combination of corticosteroids and antiviral medication.[1][2][3]

Bell palsy is the most common cause of unilateral facial paralysis. Bell palsy is more common in patients with diabetes or who are pregnant.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Bell palsy is by definition idiopathic in nature. Increasing evidence in the literature demonstrates multiple potential clinical conditions and pathologies known to manifest, at least in part, with a period of unilateral facial paralysis. The literature has highlighted several viral illnesses such as herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, and Epstein-Barr virus. Providers may ambiguously (and incorrectly) refer to a diagnosis of Bell palsy in the setting of a potentially known etiologic mechanism. This can occur, for example, in the setting of known associations (eg, Ramsay-Hunt syndrome and Lyme disease).[4]

While there are many potential causes, including idiopathic, traumatic, neoplastic, congenital, and autoimmune, about 70% of facial nerve palsies are diagnosed as Bell palsy.

Epidemiology

The annual incidence is 15 to 20 per 100,000, with 40,000 new cases yearly. The lifetime risk is 1 in 60. The recurrence rate is 8% to 12%. Even without treatment, 70% of patients will have complete resolution.

There is no gender or racial preference, and palsy can occur at any age, but more cases are seen in mid and late life, with the median age of onset at 40 years. Risk factors include diabetes, pregnancy, preeclampsia, obesity, and hypertension.[5]

Pathophysiology

Bell palsy is thought to result from compression of the seventh cranial nerve at the geniculate ganglion. The first portion of the facial canal, the labyrinthine segment, is the narrowest; most cases of compression occur in the labyrinthine segment. Due to the narrow opening of the facial canal, inflammation causes compression and ischemia of the nerve. The most common finding is a unilateral facial weakness that includes the muscles of the forehead.

History and Physical

Patients present with rapid and progressive symptoms over the course of a day to a week often reaching a peak in severity at 72 hours. Weakness will be partial or complete to one-half of the face, resulting in weakness of the eyebrows, forehead, and angle of the mouth. Patients may present with an inability to close the affected eyelid or lip on the affected side.

The key physical exam finding is a partial or complete weakness of the forehead. If forehead strength is preserved, a central cause should be investigated. Patients may also complain of a difference in taste, sensitivity to sound, otalgia, and changes to tearing and salivation.

Ocular features include the following:

- Corneal exposure

- Lagophthalmos

- Brow droop

- Paralytic ectropion of the lower lid

- Upper eyelid retraction

- Decreased tear output

- Loss of nasolabial fold

Evaluation

History and physical examination guide the evaluation. The House-Brackmann Facial Nerve Grading System can be used to describe the degree of facial nerve weakness. This grading system goes from a grade of I (no weakness) to VI (complete weakness). If the presentation is consistent with Bell palsy, no lab or radiographic tests are required. If there are atypical features, patients may need to be evaluated for a central cause of their symptoms.

Likewise, Lyme disease testing is based on a history of possible tick-borne illnesses. Routine testing for Lyme disease is not recommended without other findings such as a history of a tick bite, skin rash, or arthritis. No consensus exists on the optimal timing of imaging for Lyme disease, but most sources recommend after 2 months of no improvement of the facial palsy. Diabetic testing should not be performed as facial nerve palsy is not considered diabetic neuropathy. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the imaging modality of choice. MRI can detect facial nerve inflammation and rule out conditions such as schwannoma, hemangioma, or a space-occupying lesion.[6]

Nerve conduction studies and electromyography (EMG) may help determine outcomes in patients with severe Bell palsy. Electroneurgraphy uses EMG to monitor the difference in potentials generated by the facial muscles on both sides. If hearing loss is suspected, auditory evoked potentials and audiography should be performed. Other tests include testing for saliva flow, tear function, and nerve excitability.

There is a grading system for clinical evaluation of Bell palsy. The grading system ranges from mild-to-severe dysfunction.

Treatment / Management

Spontaneous recovery does occur; therefore, the role of treatment remains questionable.

Corticosteroids are the primary treatment, with a standard 60 to 80 mg daily regimen for approximately 1 week. Evidence reveals that combined corticosteroids and antivirals can improve outcomes compared with using corticosteroids alone.[7] However, a meta-analysis in 2009 found that steroids alone were the treatment of Bell palsy, and the addition of antivirals did not meet statistical significance.[8](A1)

Patients with severe facial nerve palsy (House-Brackmann IV or higher) can be offered combination therapy with steroids and antivirals. No significant increase in adverse reactions from antivirals compared to placebo or corticosteroids is reported. Patients should receive guidance on using eye lubrication and applying a patch to the affected eye before bedtime, aiming to minimize the risk of corneal abrasion.

The availability of botulinum toxin has helped reduce the long-term burden of this disorder.[9] Surgery is the last resort treatment and may be required in chronic cases. The facial muscles do remain viable for several years, and in these cases, complex reconstructions are available. Techniques to present eye desiccation range from eyelid weights to muscle transfers.

Facial nerve decompression is not a recommended treatment option and is considered on a case-by-case basis. Prior studies evaluating facial nerve compression have been of poor quality. Referral to a specialist, such as a plastic surgeon, neurologist, or otolaryngologist, sooner rather than later to explore more aggressive treatments is recommended if no improvement is noted within 4 weeks.[10][11][12](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Causes of peripheral seventh nerve palsy, such as Lyme disease and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, should be excluded. Other less common causes of facial palsy, including tuberculosis, HIV, trauma, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and neoplasm, should be excluded. There is a reported 10.8% misdiagnosis rate from specialty referral centers.

Also, if there are episodes of recurrence, clinicians should consider Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome. This is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome with a recurrence of facial palsy, orofacial edema, and a fissured tongue. Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome is more commonly diagnosed in females.

Prognosis

Bell palsy resolves completely without treatment in 71% of treated cases. Treatment with corticosteroids has been found to increase the likelihood of improved nerve recovery. Recurrence does occur, and one study reported a recurrence rate of 12%.[11] Another study reported up to 10% of patients with Bell palsy experienced symptomatic recurrence after a mean latency of 10 years [13].

Risk factors associated with poor outcomes include complete paralysis, age 60 or older, and decreased salivation or taste on the ipsilateral side. The longer the recovery, the more likely that residual sequelae may develop.

Complications

Some complications related to Bell palsy are as follows:

- Corneal dryness leading to visual loss

- Permanent damage to the facial nerve

- Abnormal growth of nerve fibers

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Continued monitoring of patients with Bell palsy is required to ensure recovery is progressing. If the EMG studies show less than 25% of muscles are involved, then supportive care is recommended. If the paralysis is severe, counseling is recommended.

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation recommendations are limited due to the quality of studies in the current literature. However, therapies are often prescribed at different stages of recovery. Several treatments have been mentioned in the literature, such as electrotherapy, massage, mirror therapy, and facial exercises. Tailored facial exercise programs and mirror therapy have shown the most promising results in early rehabilitation efforts. Nonetheless, further research is needed to establish standardized treatment and rehabilitation protocols.[14][15][16][17]

Consultations

Consultations that may be necessary when managing Bell palsy are as follows:

- Ophthalmologist

- Neurologist

- Otolaryngologist

- Speech pathologist

Pearls and Other Issues

As stated, the misdiagnosis rate can be up to 10.8%. Careful history collection and physical examination are essential. The focus of the physical exam is the forehead muscles. Since Bell palsy is a peripheral facial nerve palsy, the forehead muscles need to be involved. The history and physical guide testing for causes of facial nerve weakness.

Patients shouldn't be tested for Lyme disease unless they have a history of tick bite or manifestations of rash and arthritis. Patients may be treated at home medically with close follow-up to ensure improvement of symptoms. There should be a consideration for timely specialty referral if there has been little improvement in the first few weeks of the disease. There are no known preventative measures, and 8% to 12% of patients will have a recurrence.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Bell palsy is the most common cause of unilateral facial paralysis. While benign, the condition does have moderate morbidity and can lead to loss of vision. Thus, the disorder is best managed by an interprofessional team.[18]

The cause of Bell palsy remains unknown, and its treatment remains controversial. While steroids and/or antiviral medications are often prescribed, there is still debate on which treatment regimen is more effective. The problem is compounded by the fact that most cases resolve spontaneously. However, in individuals with long-standing facial paralysis accompanied by poor speech, incomplete eyelid closure, or poor aesthetics, treatment needs to be provided by an interprofessional team.[19] Because the disorder affects different organ systems, an interprofessional team of clinicians, nurses, and technologists has proven effective. The most important feature of the treatment is to be patient-focused rather than symptom-focused.

In any case, clinicians must educate the patient on eye protection and lubrication. Eye dryness should be prevented at all costs using artificial tears and other liquid preparations. If there is evidence of noncompliance or evidence that the eye is becoming dry and irritated, the nurse or pharmacist should report back to the clinical team leader.

The neurology nurse must educate the patient on facial exercises that can help improve muscle strength and facial coordination. These exercises can reduce poor aesthetics and improve the functionality of the facial muscles. If the patient is noncompliant, the nurse should report to the clinical team leader and assist with further patient education.

Outcomes

Evidence-based medicine is lacking when it comes to treatment and outcomes for Bell palsy. The problem is made more difficult because many cases resolve spontaneously. Most reported outcomes have been from case reports or small case series. While recovery does occur in most patients, it often takes months or even years for a full recovery. Because there are several types of treatments available besides medications, an interprofessional team should be involved in the management since not everyone responds to the same treatment. [20]

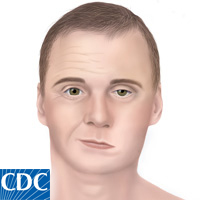

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ferreira-Penêda J, Robles R, Gomes-Pinto I, Valente P, Barros-Lima N, Condé A. Peripheral Facial Palsy in Emergency Department. Iranian journal of otorhinolaryngology. 2018 May:30(98):145-152 [PubMed PMID: 29876329]

Somasundara D, Sullivan F. Management of Bell's palsy. Australian prescriber. 2017 Jun:40(3):94-97. doi: 10.18773/austprescr.2017.030. Epub 2017 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 28798513]

Reich SG. Bell's Palsy. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). 2017 Apr:23(2, Selected Topics in Outpatient Neurology):447-466. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000447. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28375913]

Spencer CR, Irving RM. Causes and management of facial nerve palsy. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2016 Dec 2:77(12):686-691 [PubMed PMID: 27937022]

Zhao H, Zhang X, Tang YD, Zhu J, Wang XH, Li ST. Bell's Palsy: Clinical Analysis of 372 Cases and Review of Related Literature. European neurology. 2017:77(3-4):168-172. doi: 10.1159/000455073. Epub 2017 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 28118632]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMower S. Bell's palsy: excluding serious illness in urgent and emergency care settings. Emergency nurse : the journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association. 2017 Apr 13:25(1):32-39. doi: 10.7748/en.2017.e1628. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28403702]

Dong Y, Zhu Y, Ma C, Zhao H. Steroid-antivirals treatment versus steroids alone for the treatment of Bell's palsy: a meta-analysis. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015:8(1):413-21 [PubMed PMID: 25785012]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceQuant EC, Jeste SS, Muni RH, Cape AV, Bhussar MK, Peleg AY. The benefits of steroids versus steroids plus antivirals for treatment of Bell's palsy: a meta-analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2009 Sep 7:339():b3354. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3354. Epub 2009 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 19736282]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Sanctis Pecora C, Shitara D. Botulinum Toxin Type A to Improve Facial Symmetry in Facial Palsy: A Practical Guideline and Clinical Experience. Toxins. 2021 Feb 18:13(2):. doi: 10.3390/toxins13020159. Epub 2021 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 33670477]

Tseng CC, Hu LY, Liu ME, Yang AC, Shen CC, Tsai SJ. Bidirectional association between Bell's palsy and anxiety disorders: A nationwide population-based retrospective cohort study. Journal of affective disorders. 2017 Jun:215():269-273. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.051. Epub 2017 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 28359982]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCai Z, Li H, Wang X, Niu X, Ni P, Zhang W, Shao B. Prognostic factors of Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Medicine. 2017 Jan:96(2):e5898. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005898. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28079835]

Babl FE, Gardiner KK, Kochar A, Wilson CL, George SA, Zhang M, Furyk J, Thosar D, Cheek JA, Krieser D, Rao AS, Borland ML, Cheng N, Phillips NT, Sinn KK, Neutze JM, Dalziel SR, PREDICT (Paediatric Research In Emergency Departments International Collaborative). Bell's palsy in children: Current treatment patterns in Australia and New Zealand. A PREDICT study. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2017 Apr:53(4):339-342. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13463. Epub 2017 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 28177168]

De Diego-Sastre JI, Prim-Espada MP, Fernández-García F. [The epidemiology of Bell's palsy]. Revista de neurologia. 2005 Sep 1-15:41(5):287-90 [PubMed PMID: 16138286]

Singh A, Deshmukh P. Bell's Palsy: A Review. Cureus. 2022 Oct:14(10):e30186. doi: 10.7759/cureus.30186. Epub 2022 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 36397921]

Baugh RF, Basura GJ, Ishii LE, Schwartz SR, Drumheller CM, Burkholder R, Deckard NA, Dawson C, Driscoll C, Gillespie MB, Gurgel RK, Halperin J, Khalid AN, Kumar KA, Micco A, Munsell D, Rosenbaum S, Vaughan W. Clinical practice guideline: Bell's palsy. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2013 Nov:149(3 Suppl):S1-27. doi: 10.1177/0194599813505967. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24189771]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKhan AJ, Szczepura A, Palmer S, Bark C, Neville C, Thomson D, Martin H, Nduka C. Physical therapy for facial nerve paralysis (Bell's palsy): An updated and extended systematic review of the evidence for facial exercise therapy. Clinical rehabilitation. 2022 Nov:36(11):1424-1449. doi: 10.1177/02692155221110727. Epub 2022 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 35787015]

Martineau S, Rahal A, Piette E, Moubayed S, Marcotte K. The "Mirror Effect Plus Protocol" for acute Bell's palsy: A randomized controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Clinical rehabilitation. 2022 Oct:36(10):1292-1304. doi: 10.1177/02692155221107090. Epub 2022 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 35722671]

Eviston TJ, Croxson GR, Kennedy PG, Hadlock T, Krishnan AV. Bell's palsy: aetiology, clinical features and multidisciplinary care. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2015 Dec:86(12):1356-61. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309563. Epub 2015 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 25857657]

Butler DP, Grobbelaar AO. Facial palsy: what can the multidisciplinary team do? Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare. 2017:10():377-381. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S125574. Epub 2017 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 29026314]

Glass GE, Tzafetta K. Bell's palsy: a summary of current evidence and referral algorithm. Family practice. 2014 Dec:31(6):631-42. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmu058. Epub 2014 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 25208543]