Introduction

Rudolf Balint first described Balint syndrome in 1909. In his original observations, Balint described the patient's clinical symptoms, which included:

- An inability to visualize more than one object in the visual field at a time (psychic paralysis of gaze or visual inattention)

- An inability to identify different items in a visual scene simultaneously (a spatial disorder of attention or simultagnosia)

- A failure to reach an object with his right hand but able to do so with the left hand. (Misreaching or optic ataxia).

The patient had normal visual acuity, color vision, and intact extraocular muscle movements, and his autopsy revealed changes suggestive of chronic cerebrovascular disease in bilateral posterior parietal lobes. The postulation then was that the symptoms were from a lack of coordination between sensory input and motor output.

In 1919, Holmes and Horrax described another case with a similar presentation, but the authors postulated that the patient’s inability to touch or point to objects was due to visual disturbances only. They considered that the patient had no trouble in performing sensory or motor tasks that did not need visual input, hence the primary deficit had to be in visual fields.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Balint syndrome commonly results from ischemic infarctions in bilateral parietal and occipital areas.

There are also reports of Balint syndrome with other neurological disorders such as[2]:

- Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES)

- Alzheimer disease

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD)

- Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA)

- Corticobasal degeneration (CBD)

- Subacute HIV encephalitis

- Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML)

- Head trauma

- Cerebral toxoplasmosis, and

- Brain metastasis

Two recent reports exist of cases of NMDA receptor encephalitis with a clinical presentation that was consistent with Balint syndrome.[3] There is also a case of idiopathic Balint syndrome.[4]

Epidemiology

Literature regarding Balint syndrome exists mostly in the form of case reports. There are no reports of the exact incidence and prevalence of Balint syndrome. Reports are usually in the adult population, but several case reports exist in the pediatric population as young as 4 years.[5]

Pathophysiology

Lesions involving bilateral parietal areas and occipital areas in some cases, due to the causes mentioned above, result in clinical features that present in Balint syndrome. Among the various etiological factors, ischemic infarction due to multiple causes appears to be the most common etiology of Balint syndrome.

History and Physical

Balint syndrome, as described initially, is a rare disorder associated with difficulties in visual and spatial coordination and is characterized by the three cardinal features:

- Optic ataxia

- Oculomotor apraxia

- Simultagnosia

Optic ataxia is the lack of coordination between visual input and hand movements. For example, the patients can accurately touch their own body voluntarily, but when given a visually guided task, they are unable to complete it. However, once provided proprioceptive or auditory cues to reach for a target object, they can perform the task smoothly. Theories are that this deficit may arise due to damage to the superior parietal lobule, which is responsible for coordination between visual input and hand movements.[6] Isolated optic ataxia may occur from lesions in Broadman’s areas 5, 7, 19, 37, and 39.[7] Although existing literature suggests that parietal and occipital lobes are the primary areas of involvement in Balint syndrome, lesions in other areas of the brain such as the prefrontal cortex and frontal eye fields were reported to be associated with individual symptoms of Balint syndrome.[7]

Oculomotor apraxia is the inability to voluntarily shift gaze despite the intact function of extraocular muscles. Although described initially in patients with bilateral parietal lesions, later studies have shown that isolated lesions of frontal eye fields can also cause this deficit.[8]

Simultagnosia is the lack of ability to perceive more than a single object at a time. For example, when provided with a picture of a forest with trees, they are unable to see the forest, although they can see each individual tree. Because of their attentional visual deficit, they can appear to be functionally blind and will have difficulty reading and counting because these activities require viewing more than one object at a time. It further classifies as dorsal and ventral types. In the dorsal variant, the lesion is postulated to be in the bilateral parietal lobes, and the patient is often unable to see more than one object at a time. In the ventral type, the lesion is postulated to be in the left inferior occipitotemporal lobe, and the patient has a slower visual processing speed and is unable to identify individual parts of a multi-part object.[9]

The three defining features of Balint syndrome involve a lack of coordination between visual inputs and motor outputs, which causes an inability to use visual information to guide the patient’s hands or eyes. Patients with this syndrome have normal visual acuity, do not have paralysis of extraocular movement, and can name colors and objects.

Evaluation

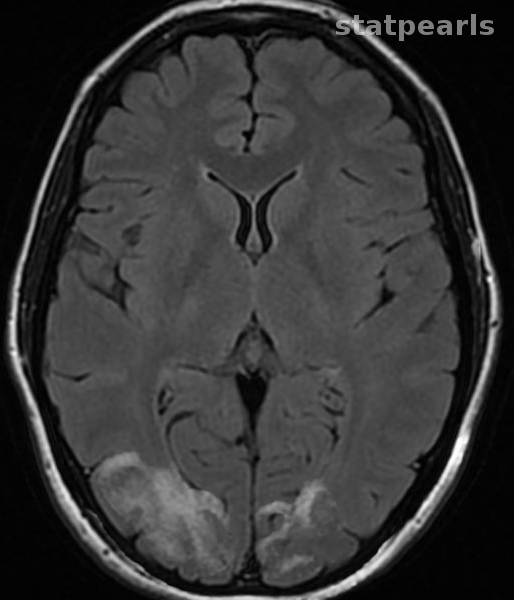

Balint syndrome is suspected clinically based on the symptoms described above in the clinical features section. Lack of proper understanding of this syndrome often results in misdiagnosis of the presentation. No specific diagnostic criteria exist for imaging studies of the brain. Computed tomogram (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain usually reveal atrophic changes in parietal and occipital lobes. However, Balint syndrome imaging studies may depict findings consistent with underlying etiology. Subsequent diagnostic studies are performed to delineate the etiology once there is clinical suspicion for Balint syndrome, and imaging findings are consistent with clinical presentation. In some cases, single positron emission computed tomography scan may be needed to evaluate for cerebral hypoperfusion of the involved areas.[4]

Treatment / Management

The core management of Balint syndrome relies on rehabilitation and reducing the extent of disability to a bare minimum. In some instances such as infarction, PRES, and infectious etiologies, secondary preventive measures can be employed to reduce the risk of recurrence. There are different approaches in occupational rehabilitation that have been proposed to help individuals limit their disabling symptoms. The adaptive approach is where the intact abilities are used effectively to reduce the extent of disability caused by the symptoms. The remedial approach aims to repair the damaged areas of the brain by training them in perceptual skills. The third and complex approach is a multi-context approach that involves strategic learning in an environment with multiple tasks.[10](B3)

Differential Diagnosis

Hemineglect, which usually results from lesions in the temporoparietal junction, should be distinguished from Balint syndrome. In patients with hemineglect defective eye movements may mimic ocular apraxia, difficulty in performing hand movements may mimic optic ataxia, and deficits in perception can mimic simultagnosia.[7]

Prognosis

The prognosis of Balint syndrome depends mostly on the underlying etiology. In acute etiologies such as stroke, infectious origin, or PRES, with appropriate management, a good prognosis may be seen in patients. On the other hand, Balint syndrome secondary to neurodegenerative etiologies such as corticobasal degeneration or posterior cortical atrophy correlates with poor prognosis.

Complications

Other than the disabling symptoms associated with the syndrome, there are no reports of significant complications in patients with Balint syndrome.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Although a rare presentation, if a patient experiences any symptoms such as lack of hand-eye coordination, inability to focus on more than one thing, and problems with seeing different objects in their visual field, evaluation by a neurologist is necessary to rule out Balint syndrome.

Pearls and Other Issues

The original description of Balint syndrome was a triad of symptoms occurring from lesions in bilateral parietal lobes, but over the years there have been numerous case reports wherein the lesions involved parietooccipital or temporooccipital areas, with similar clinical presentations. Furthermore, individual components of Balint syndrome can occur as a result of other lesions involving parts of the brain other than the parietal and occipital lobes. Further studies are needed to analyze the specific neuronal pathways that are responsible for the clinical presentations described commonly with Balint syndrome.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As the condition is rarely seen even by neurologists, the patient who presents with an inability to shift his gaze voluntarily despite the presence of normal extraocular movements may be suspected to have conversion disorder and may not receive an appropriate evaluation. Education of health care professionals at various levels including physicians, nurses, and other health care providers about the symptomatology of this presentation is essential in making sure that patients are appropriately evaluated. Diagnosing and treating Balint syndrome requires an interprofessional team approach, including physicians, specialists, and specialty-trained nurses, all collaborating across disciplines to achieve optimal patient results. [Level 5]

Media

References

Moreaud O. Balint syndrome. Archives of neurology. 2003 Sep:60(9):1329-31 [PubMed PMID: 12975305]

Kumar S, Abhayambika A, Sundaram AN, Sharpe JA. Posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome presenting as Balint syndrome. Journal of neuro-ophthalmology : the official journal of the North American Neuro-Ophthalmology Society. 2011 Sep:31(3):224-7. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31821b5f92. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21566529]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMetzger A, Pisella L, Vighetto A, Joubert B, Honnorat J, Tilikete C, Desestret V. Balint syndrome in anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. Neurology(R) neuroimmunology & neuroinflammation. 2019 Jan:6(1):e532. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000532. Epub 2018 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 30588484]

Ghoneim A, Pollard C, Greene J, Jampana R. Balint syndrome (chronic visual-spatial disorder) presenting without known cause. Radiology case reports. 2018 Dec:13(6):1242-1245. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2018.08.026. Epub 2018 Sep 20 [PubMed PMID: 30258515]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePhilip SS, Mani SE, Dutton GN. Pediatric Balint's Syndrome Variant: A Possible Diagnosis in Children. Case reports in ophthalmological medicine. 2016:2016():3806056 [PubMed PMID: 27895948]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmalnath SD, Kumar S, Deepanjali S, Dutta TK. Balint syndrome. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2014 Jan:17(1):10-1. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.128526. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24753652]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRizzo M, Vecera SP. Psychoanatomical substrates of Bálint's syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2002 Feb:72(2):162-78 [PubMed PMID: 11796765]

Chechlacz M, Humphreys GW. The enigma of Bálint's syndrome: neural substrates and cognitive deficits. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2014:8():123. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00123. Epub 2014 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 24639641]

Battaglia-Mayer A, Caminiti R. Optic ataxia as a result of the breakdown of the global tuning fields of parietal neurones. Brain : a journal of neurology. 2002 Feb:125(Pt 2):225-37 [PubMed PMID: 11844724]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl-Khawaja I, Haboubi NH. Neurovisual rehabilitation in Balint's syndrome. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2001 Mar:70(3):416 [PubMed PMID: 11248903]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence