Introduction

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous, filamentous fungus that primarily causes infection in immunocompromised hosts and individuals with underlying pulmonary disease.[1][2] In the environment, Aspergillus species obtain nutrients from dead material and reproduce asexually via conidia.[3][1] Over twenty-four species of Aspergillus are capable of causing human disease, but A. fumigatus, followed by A. terreus and A. flavus, is the most implicated as a pathogen.[4] Although caused by the same genus of fungi, aspergillosis should be thought of as a spectrum of processes that vary widely depending on the host's immune status. Thus, the implications can vary from life-threatening, as is noted in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis and invasive rhinosinusitis seen in the severely immunocompromised, to non-urgent in the case of small aspergillomas in the immunocompetent, where monitoring with serial imaging is appropriate in most cases.[5][6]

There are three major types of bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: invasive aspergillosis, chronic aspergillosis, and allergic aspergillosis.[5] Although transmission is via aspiration of conidia, most people inhaling conidia will not contract aspergillosis due to immune response.[5][7] Neutrophils are noted as the most important immune cell in the immune response against Aspergillus species.[7] If left untreated, invasive aspergillosis has mortality approaching 100%.[8] In cases of suspected invasive aspergillosis, an extensive diagnostic workup is necessary, but treatment should be initiated as soon as possible to reduce morbidity and mortality.[9][10]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The primary route of infection and cause depend on the clinical syndrome.

Pulmonary

Pulmonary aspergillosis is contracted via inhalation of Aspergillus conidia.[5] Aspergillus is ubiquitous in the environment, present in concentrations between 1 and 100 m, depending on whether the location is indoors or outdoors. It can be higher in certain areas, such as where the soil is disturbed.[11] In invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) and invasive bronchial aspergillosis (IBA), the root cause is an inadequate immune response, allowing for the fungus's growth and invasion.[1] In chronic pulmonary aspergillosis, the cause is colonization in the setting of structural lung disease, such as prior cavitary disease from another process, such as tuberculosis.[1] In allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) and severe asthma with fungal sensitization (SAFS), the root cause is an allergic reaction to the inhaled fungal elements.[1] The allergen involved in ABPA is almost always A. fumigatus.[1]

Rhinosinusitis

Rhinosinusitis is contracted via the inhalation of conidia via the nasal route and predominantly occurs in severely immunocompromised hosts.[7] However, chronic granulomatous invasive rhinosinusitis occurs in immunocompetent patients.[6] The most common organism associated with this is A. flavus.[6]

Cerebral

Aspergillus species reach the brain either hematogenously in the case of disseminated infection or via direct extension from contiguous areas, such as the mastoid, middle ear, or paranasal sinuses.[12]

Endophthalmitis

Cataract surgery can serve as the entry point for Aspergillus species, causing fungal endophthalmitis.[13] Keratitis caused by Aspergillus species is often associated with contact lenses or other substances that damage the corneal epithelium, which increases the risk of infection.[14][15]

Osteomyelitis

Aspergillus enters the bone via disseminated infection in severe immunocompromise or direct inoculation, such as intravenous drug use[16] or surgical site infection.[17]

Cutaneous

An entry into the skin via venous catheters, predisposing chronic inflammatory skin condition, or trauma is necessary.[18] Burns allow for an ample portal of entry for Aspergillus species.[19] Aspergillus species have been increasingly recognized as a cause of onychomycosis, with nail trauma, immunodeficiency, and exposure of the nails to the soil as gateways to procuring this infection.[20]

Disseminated and Other Sites

Disseminated infections often originate from one of the sites above in the immunocompromised host, but dissemination from the pulmonary route is common.[21] Growing hyphae gain access to the bloodstream by breaking through the endothelium of blood vessels.[21] Endocarditis is rarely observed; most patients have had recent cardiac surgery or are severely immunosuppressed with disseminated disease.[22] Rarely, gastrointestinal aspergillosis has also been observed, in which fungal conidia are ingested.[23] Profound immunosuppression and the presence of underlying mucositis are thought to contribute.[23]

In the past, it has been challenging to identify the exact species causing disease in many cases, leading to reporting the isolates as part of a complex. However, molecular diagnostics have helped aid in identification.[24] Aspergillus fumigatus has previously been thought to be the cause of around 90% of invasive aspergillosis.[25] However, more recent studies have reported that they comprise a smaller proportion, although they remain predominant.[26]

Epidemiology

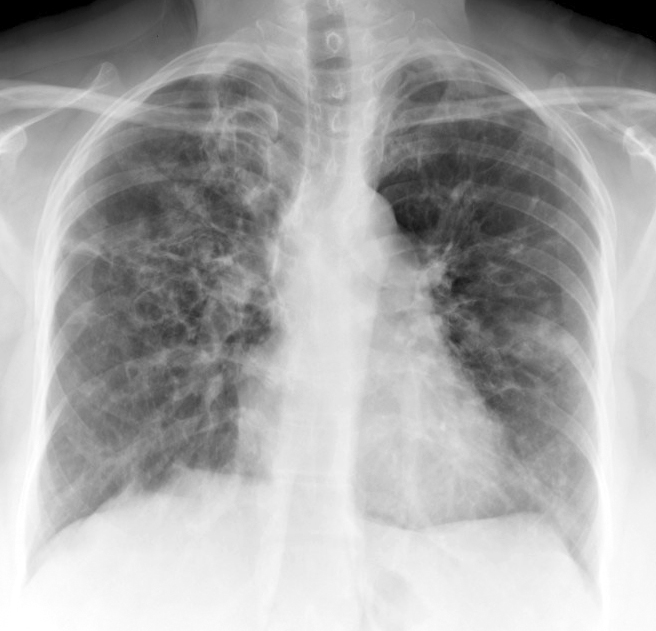

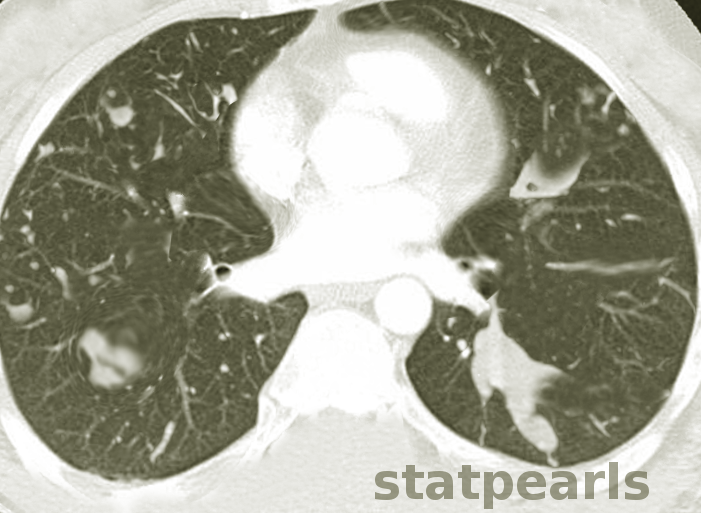

Invasive aspergillosis overwhelmingly affects the immunocompromised population, composed of patients with AIDS, those with hematologic malignancies, prolonged neutropenia, long-term corticosteroids, and recipients of transplants on anti-rejection medications.[27][28][29][28][27][30] Incidence after a hematopoietic stem-cell transplant (HSCT) ranges from 0.5% after an autologous stem-cell transplant to up to 3.9% after a transplant from an unrelated donor.[31] Invasive aspergillosis is also be seen in critically ill intensive care patients with an underlying pulmonary condition such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma (see Image. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis).[30] Around 250,000 cases of invasive aspergillosis are estimated to occur globally yearly.[32] Invasive aspergillosis has affected those with severe influenza and, more recently, severe COVID-19.[33][34] The incidence of invasive aspergillosis in hospitalized patients rose by 44% between 2004 and 2013.[35] The increase in incidence is seen as transplantation is becoming more accessible and is utilized more often.[36]

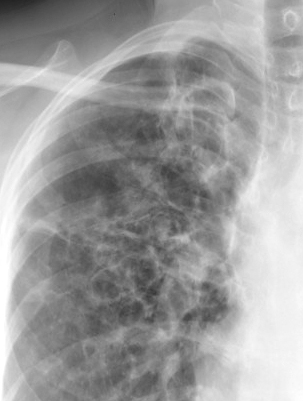

Patients with underlying lung diseases such as chronic obstructive lung disease, tuberculosis, asthma, lung cancer, and sarcoidosis are at risk for developing the chronic form of aspergillosis.[5] Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis is almost exclusively found in asthma and cystic fibrosis patients (see Image. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Allergy Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis, Close-Up View).[37] Those working in the construction, farming industries, and wastewater treatment plants may be at increased risk of Aspergillus infection due to chronic exposure in their work environments.[38] Smoking marijuana contaminated with the fungus may also place an individual at risk for infection.[39] Nosocomial Aspergillus infections have been reported from hospital showers and healthcare facilities undergoing construction.[40]

Pathophysiology

In an immunocompetent person, Aspergillus conidia are inhaled and taken up by phagocytes in the lungs.[1] Neutrophils, pulmonary macrophages, and pulmonary epithelial cells play a crucial role.[1] The conidia germinate into hyphae at body temperature. Phagocytes are attracted when proteins from the fungal cell wall, such as beta-1,3-glucan, activate major immune effector pathways, which activate alveolar macrophages.[1] Neutrophils are attracted via released cytokines and kill the invasive hyphae via the release of NADPH-dependent reactive oxygen species,[7] and the Aspergillus infection is kept at bay.[41] If any of these mechanisms are impaired in an immunocompromised patient, the infection may be allowed to spread.[42]

Aspergillus is notable for angioinvasion, with thrombosis of blood vessels causing tissue necrosis and allowing spread to distant sites.[5]

In patients with underlying pulmonary disease, colonization of Aspergillus in a preexisting cavity allows a large mass of fungal hyphae, fibrin, and other debris to form an aspergilloma.[5]

In the case of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA), Aspergillus conidia do not trigger the typical immune response and instead activate TH2 CD4 T-cells.[5]

Histopathology

Correctly sending appropriate specimens is paramount for accurate and timely diagnosis.[43] Tissue, aspirates, and fluids (such as bronchoalveolar lavage) obtained from the affected organs or area of concern are ideal specimens.[43] Additionally, although fungal features are readily apparent in formalin-fixed tissue, it is essential to consider that formalin fixation sterilizes the biopsy. Therefore, culture and susceptibility data and exact species identification will not be available. Sending tissue for culture in a sterile tube or container along with a formalin-fixed specimen will speed diagnosis and the receipt of crucial information.

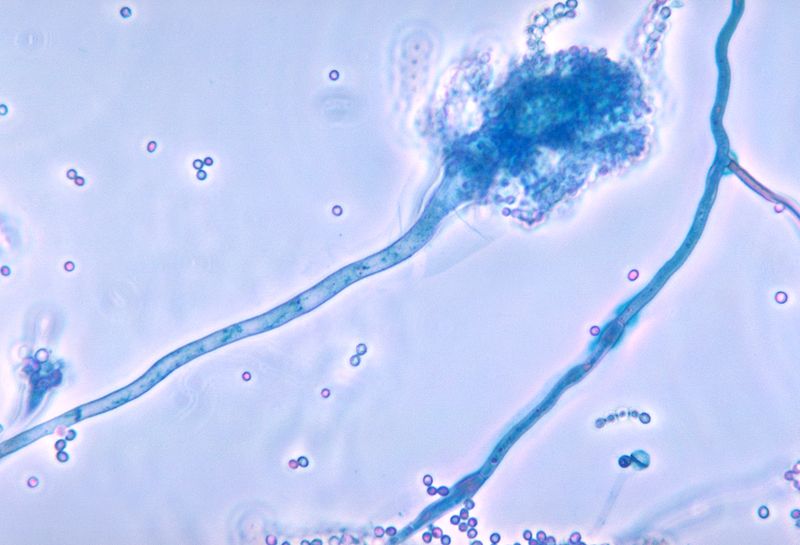

Stains often employed while examining Aspergillus species include Periodic acid-Schiff and Gomori's methenamine silver stain.[43] Fluorescent dye such as Calicoflor white is often used as well.[43] Non-septate hyphae are observed that exhibit dichotomous branching.[43] Several species of Aspergillus have characteristic features. Aspergillus fumigatus is notable for having a uniseriate conidiophore with phialides sporulating from the upper two-thirds of the vesicle.[44] A. niger is notable for having larger conidia (see Image. Aspergillus Fumigatus).[44] Patients with hematological malignancies with invasive aspergillosis with bronchoalveolar lavages with positive Gomori's methenamine silver stain were noted with a higher rate of cavitary disease or culture positivity of more than one species of Aspergillus than those that did not stain positive.[45]

Tissue pathology from patients with invasive fungal sinusitis reveals pale and necrotic mucosa, as infarction occurs due to angioinvasion of the fungi.[6] Evaluation of vessel walls reveals occlusion and evidence of invading fungal hyphae.[6]

History and Physical

A thorough history and physical exam should be performed on every patient suspected of having an Aspergillus infection. Care should be taken to understand a patient’s risk factors for invasive disease and focus on eliciting all history related to immunosuppression. A careful history of any chemotherapy, glucocorticoids, and immunosuppressants received should be elicited. Attention should be paid to any history of malignancy with detailed treatment history, including a history of ibrutinib, fludarabine, venetoclax use, or history of CAR-T therapy.[7]

Transplant history should be noted with a careful review of the post-transplant course, including the history of graft versus host disease and length and depth of any neutropenia. A history of lung disease and any environmental exposures, such as construction work, gardening, or work in wastewater treatment, should be noted carefully. History should also delve into recent pulmonary infections like COVID-19 or influenza. Finally, the clinician should investigate in-depth current and past medical problems to assess the potential for an immunocompromised state, including taking a detailed sexual history to assess the likelihood of HIV and carefully reviewing the history for frequent infections that could raise concern for immunodeficiency, such as chronic granulomatous disease.

The invasive aspergillosis patient will often be critically ill with immunocompromised status. This condition should also be considered in critically ill patients with underlying lung disease. The most common initial symptoms of pulmonary infection include fever, worsening dyspnea, increased sputum production, hemoptysis, and pleuritic chest pain. Fever may not manifest in the severely immunocompromised; therefore, fever can be absent, despite progressive infection.[5] Invasive fungal sinusitis often presents with vague symptoms, but facial pain, retro-orbital pain, exophthalmos, visual impairment, nasal congestion, and fever can be noted.[46] Invasive aspergillosis rapidly progresses, and symptoms often manifest once the disease is advanced.

Chronic pulmonary aspergillosis most commonly presents with a cough.[5] Due to lung vascularity, hemoptysis is seen around half the time due to encroachment on the involved vessels.[5] Hemoptysis may be the first presenting symptom. Systemic symptoms, including fever, night sweats, and weight loss, are more commonly seen in the disease’s cavitary, fibrosing, and necrotizing forms.[5] In contrast, patients with small aspergillomas or nodules may be asymptomatic and have normal physical examinations.[5]

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis will present with recurrent asthma exacerbations, with the most prominent finding being dyspnea and wheezing, along with coughing up large amounts of sputum with brown plugs.[37]

Physical examination findings vary depending on the infected area. There may be sinus tenderness, nasal discharge, pallor or necrosis of the oral or nasal mucosa or conjunctiva, new mobility or hypesthesia of teeth, proptosis, or cranial nerve abnormalities in invasive fungal rhinosinusitis.[47] Rales, rhonchi, dullness to percussion, and bloody sputum or endotracheal tube secretions may be seen in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Wheezing is often noted with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis.[5] Dermatologic changes such as purpuric lesions, eschar, or meningeal signs can signal disseminated infection. However, a normal physical examination does not rule out invasive infection. The physical examination in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis depends on the extent of the infection and underlying pulmonary disease.

Evaluation

A strong clinical suspicion for aspergillosis should prompt the evaluation due to the ubiquitous nature of Aspergillus conidia in the environment. The presence of Aspergillus in a sputum sample in and of itself does not indicate infection unless other signs, symptoms, and host risk factors are present. Alternatively, invasive aspergillosis can present with subtle symptoms.[7] Evaluation should proceed based on the suspected clinical syndrome.

Invasive Fungal Rhinosinusitis

Suspicions of invasive fungal rhinosinusitis should prompt emergent evaluation by an otolaryngologist so that nasal endoscopy with culture collection or other surgery can be performed urgently. These patients should be managed by infectious disease clinicians, otolaryngologists, and transplant physicians (if appropriate). Adjunctive imaging, such as CT of the maxillofacial sinuses and MRI of the brain, helps to evaluate for bone abnormalities and characterize the extent of sinus disease. However, one should note that CT can underestimate the extent of the infection, and MRI may better characterize disease progression.[48]

Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Patients with suspicions of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis should undergo chest CT to evaluate the presence or extent of the disease as well as to direct further efforts, such as bronchoscopy.[49] If lesions are amenable to this approach and there are no contraindications, patients should undergo bronchoscopy. The procedure will allow for the inspection of the airways and collection of tissue for fungal culture and cytopathology, as well as to collect deep lower respiratory fungal cultures and galactomannan.[49] Alternatively, they should have sputum cultures collected for fungal culture and stain if bronchoscopy cannot be performed. These patients should be managed with the help of infectious disease clinicians, pulmonologists, and transplant physicians (if appropriate). Culture of the Aspergillus species in the sputum or by bronchoalveolar lavage supports the diagnosis of aspergillosis, but tissue sampling revealing invasive Aspergillus hyphae finalizes the diagnosis.[49]

Patients within the first three months of lung transplant are at risk of invasive fungal infection at the anastomosis of the transplant.[49] This risk is the highest in the first 3-4 weeks post-transplantation.[50] Anastomotic infections can be noted upon routine screening bronchoscopy and generally requires debridement at the anastomotic site.[49]

Biomarkers and Other Laboratory Investigations

Serum biomarkers such as galactomannan are helpful in the right population. It has the best-studied utility in patients with hematologic malignancy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, with an approximate 70% sensitivity.[49] Sensitivity decreases in other patient populations and is noted to be as low as 20% in the solid organ transplant population.[49] For this reason, serum galactomannan is recommended as a biomarker in patients with hematologic malignancy and hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients not receiving mold prophylaxis.[49][51] When an optical density (OD) of 0.5 is used, galactomannan is noted to have a sensitivity of 97.4% in detecting invasive aspergillosis or probable invasive aspergillosis.[52]

Galactomannan can also be measured from bronchoalveolar lavage samples and has a sensitivity of 93.2% when an OD of 0.5 is used.[53] Causes of false-positive galactomannan include blood transfusion, use of certain crystalloids in collecting bronchoalveolar lavage samples, intravenous amoxicillin formulations, and has been reported after eating ice pops.[49][54][51] There is also cross-reactivity with Fusarium, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, and Talaromyces species.[49][51]

1,3-beta-D-glucan tests are very sensitive but are nonspecific as this is a component of the fungal cell wall and is not specific to Aspergillus species.[49] There are also many causes of false-positive tests, including membrane filters used for blood processing such as dialysis, drugs such as beta-lactams and beta-asparaginase, and contamination of blood collection tubes with glucan.[49]

It should be noted that blood cultures are very rarely positive for Aspergillus species, even with a severe disease burden of disseminated disease.[55] PCR is not widely available, but further work is being done in this area.[55][49]

Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Several criteria must be met to diagnose chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. At least three months of pulmonary symptoms, systemic symptoms, or progressive characteristic radiologic findings must be noted along with microbiology or serology confirming Aspergillus involvement.[49] Furthermore, this must be accompanied by a compatible underlying pulmonary condition in the setting of immunocompetency to make the diagnosis.[49] A positive Aspergillus IgG can also help diagnose chronic aspergillosis.[49][56] A tissue biopsy of an aspergilloma may help confirm the diagnosis and exclude alternative conditions that may cause lung masses.[2][57]

Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis (ABPA)

Patients with cystic fibrosis or asthma suspected of allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) should undergo Aspergillus skin testing or IgE against A. fumigatus, chest imaging, a measurement of total IgE level, A. fumigatus specific IgG, serum precipitins, and blood eosinophil count. Patients noted to have positive Aspergillus skin testing or IgE, total IgE greater than 1000 IU/mL, and at least two of the three other criteria meet diagnostic criteria for ABPA (see Image. Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis).[5] Other criteria include positive A. fumigatus specific IgG or serum precipitins, blood eosinophil count greater than 500 cells/L without systemic corticosteroids use, and chest imaging consistent with ABPA.[5]

Rare Manifestations

Rarely is a thoracentesis required for pleural effusion. A rare manifestation of aspergillosis includes black pleural effusion, rarely reported with Aspergillus niger infection.[58]

Radiology

Radiology is a critical adjunct for the diagnosis of aspergillosis.[59] Aspergillomas can be seen on chest radiographs and CT of the chest as a well-defined mass within a pre-existing cavity.[60] See Image. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis, CT Scan. Characteristic findings of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis include the halo sign, which consists of a central nodule surrounded by ground-glass changes.[60] The nodule consists of the invasive Aspergillus, and the ground-glass opacities are observed due to the surrounding thrombosis and hemorrhage.[60] Although the halo sign is the most characteristic sign of invasive aspergillosis, nodules without the surrounding ground-glass changes are seen more commonly.[60] The air crescent sign is often seen later in invasive aspergillosis and consists of a crescent of air around a macronodule.[60] This sign is seen much later in the course of the infection after recovery of neutrophils.[60]

In chronic, necrotizing aspergillosis, consolidation can be seen that generally starts in the upper lobes with bronchiectasis that evolves into cavitation.[61] Pleural thickening can be noted by lung cavities, which is concerning for locally invasive disease.[60] In allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, dilation of central airways with mucoid impaction is observed, and branching "finger-in-glove" opacities are often noted due to the prevalence of mucoid impaction.[60][61] Additionally, "toothpaste shadows" can transiently be seen, caused by mucus plugging.[5]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of suspected invasive aspergillosis should be promptly initiated while investigations are ongoing due to the rapidly progressive nature of the infection. When selecting an antifungal, one must consider the general resistance profiles of Aspergillus species in the area of practice, the history of anti-mold prophylaxis used (if any), the species of Aspergillus involved, if known, and the patient's comorbidities, such as QT prolongation.[49] It should be noted that A. terreus and A. alliaceus are intrinsically resistant to amphotericin B, and A. calidoustus is intrinsically resistant to azoles.[51](A1)

In most instances, the drug of choice is voriconazole.[49] Voriconazole troughs should be monitored four to seven days into therapy and after dosage changes or changes in other medications that could affect levels to ensure therapeutic levels.[49] Additionally, clinicians should counsel patients regarding the side effects of voriconazole, including photosensitivity. Although there have been previous concerns regarding an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in patients receiving voriconazole, prior studies may have been confounded by the patient's transplant status. A large study of patients treated with voriconazole for chronic aspergillosis did not reveal an increased rate of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin.[62] Alternatives therapies for invasive aspergillosis include liposomal amphotericin B or isuvaconazole.[49](A1)

For patients receiving mold prophylaxis with voriconazole, liposomal amphotericin B is recommended to be used until susceptibility testing is available.[49] When, if ever, a combination of azole and echinocandin therapy is needed is somewhat controversial but has been used for extremely ill patients.[49][51] It is also vital to decrease immunosuppression to the furthest extent possible if it is medication-induced or improve immunosuppression via treatment in the case of HIV or primary immunodeficiency.[49] Therapy should continue at least a six to twelve-week course but may need to be continued longer based on the extent of the disease and immunosuppression.[63][64] Repeat chest CT is recommended after two weeks of therapy to monitor for improvement. This interval may need to be shorter if nodules or other signs of invasive disease are noted sufficiently proximal to major blood vessels. In these cases, surgery may also be considered to avoid pulmonary hemorrhage.(A1)

Treatment of patients with chronic pulmonary aspergillosis exhibiting pulmonary symptoms and loss of pulmonary function is accomplished with oral therapy with itraconazole or voriconazole.[49] A minimum of six months of therapy for all patients is recommended, though lifelong therapy may be necessary for patients with chronic progressive disease.[49] In the case of azole resistance, micafungin, caspofungin, or liposomal amphotericin B should be considered.[49] Tranexamic acid can manage hemoptysis, but surgical resection is considered for severe cases.[49] Treatment response is measured through evaluation of symptoms, pulmonary function testing, and following Aspergillus IgE.[49] Repeat imaging (CT) may show the decreased size of aspergillomas and cavitary lesions. Repeat imaging should be done after a minimum of two weeks of therapy.[49](A1)

Surgery may be required to remove an aspergilloma and should be considered in cases of hemoptysis.[49] Surgery is most effective in patients with a single lesion and not diffuse disease. Therapeutic embolization to control hemoptysis is another way to manage symptoms though it is not curative of the disease.[65] In cases of small aspergillomas not encroaching on blood vessels, watchful waiting is appropriate without antifungal therapy if there is no increase in cavity size over six to twenty-four months.[49](A1)

Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis exacerbations are typically treated with corticosteroids to control the immune response and itraconazole to decrease the fungal burden.[49](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Asthma

- Atypical mycobacterial infection

- Bacterial pneumonia

- Bacterial sinusitis with abscess

- Blastomycosis

- Bronchiectasis

- Cavitary lung cancer

- Cavitary polyangiitis with granulomatosis

- Coccidioidomycosis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Eosinophilia

- Eosinophilic pneumonia

- Histoplasmosis

- Hypersensitivity pneumonitis

- Interstitial lung disease

- Nocardiosis

- Pulmonary sarcoidosis

- Tuberculosis

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

A landmark trial in 2002 noted decreased mortality in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis patients treated with voriconazole (survival rate at twelve weeks: 70.8%) versus amphotericin B deoxycholate (survival rate: 57.9%).[66] There was also a noted increased rate of remission in the voriconazole group.[66]

Prognosis

The prognosis of allergic bronchopulmonary pulmonary aspergillosis is good in patients with mild alterations in function.[37] However, many patients may require steroids for a prolonged time if the diagnosis is delayed.[37] Delays in diagnosis may lead to steroid resistance and the development of lung fibrosis.[67]

For patients with invasive aspergillosis, the prognosis is poor.[68] Despite appropriate antifungal therapy, the mortality rate of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is around 20% six weeks from diagnosis.[7] Once the infection has spread to the CNS, the mortality is close to 100%.[69]

Complications

- Continued wheezing

- Lung fibrosis

- Hemoptysis

- Respiratory failure

- CNS infection

- Endocarditis

- Death

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

Patients with invasive aspergillosis often require prolonged hospitalizations due to their critical illness.[70]

Consultations

- An infectious disease consultation is imperative in invasive aspergillosis and can be helpful in other forms of aspergillosis to manage antifungal therapy.

- Pulmonology evaluation is highly recommended for patients with pulmonary forms of aspergillosis.

- Otolaryngology evaluation is imperative when invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is suspected.

- Those with allergic aspergillosis may also need a referral to an allergist.

- A thoracic surgeon should be consulted to evaluate patients who do not respond as expected to antifungal therapies or have hemoptysis.

- An interventional radiologist may be very helpful for embolization therapy in patients with acute hemoptysis.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The best way to decrease morbidity and mortality from aspergillosis is to place hospitalized patients at risk of invasive aspergillosis in private rooms with HEPA filtration, lowering fungi concentration.[49] Additionally, patients at high risk for invasive aspergillosis should be directed to avoid environmental exposures that expose them to high fungal burdens, such as gardening, time in construction areas, or high-risk jobs such as wastewater treatment.[49]

In select patients, prophylactic antifungal therapy decreases the risk of fungal infections. Antifungal prophylaxis with voriconazole or posaconazole is recommended for patients with several risk factors. These include prolonged periods of neutropenia from chemotherapy, allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, severe or prolonged graft-versus-host disease, lung transplant within the first 3-4 months post-transplantation, and some other solid organ transplant recipients.[49] Additionally, for lung transplant patients with Aspergillus airway colonization within the first six months of transplant or that have received increased immunosuppression for rejection within the last three months, it is recommended that they preemptively receive a course of antifungal therapy.[49]

Pearls and Other Issues

When aspergillosis is suspected, remembering the following pearls is helpful:

- Send all tissue and fluid for cytology, culture, and histopathology.

- If invasive pulmonary aspergillosis is suspected, anti-fungal therapy and CT chest should be ordered. Bronchoscopy should be considered if possible.

- Galactomannan is a valuable adjunct in diagnosing invasive aspergillosis in patients with hematological malignancies and those with a history of hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

- Fungal rhinosinusitis is a medical emergency, and the patient should be evaluated by otolaryngology urgently for consideration of surgical management.

- The halo and air crescent signs are radiographic signs of invasive aspergillosis.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Aspergillosis has a better prognosis in immunocompetent individuals but is very guarded in transplant and immunocompromised patients. Evidence-based guidelines are recommended to be followed in managing all cases of invasive fungal disease. An interprofessional team should include healthcare professionals from various disciplines to assist with care, including infectious diseases clinicians, pulmonologists, otolaryngologists, transplant physicians, pathologists, microbiology laboratory personnel, nurses, pharmacists, and infectious diseases pharmacists. Open communication among consultants and adherence to clinical pathways is critical to expedite care and decrease mortality. Integrated diagnostic measures for aspergillosis, including appropriate imaging, galactomannan, and bronchoscopy in appropriate patients, is critical to expedite the diagnosis. [Level 1, Level 3] When there is clinical suspicion of invasive aspergillosis, the patient must be immediately started on targeted antifungal agents.[71] [Level 1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Latgé JP, Chamilos G. Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillosis in 2019. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2019 Dec 18:33(1):. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00140-18. Epub 2019 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 31722890]

Jenks JD, Hoenigl M. Treatment of Aspergillosis. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2018 Aug 19:4(3):. doi: 10.3390/jof4030098. Epub 2018 Aug 19 [PubMed PMID: 30126229]

Henß I, Kleinemeier C, Strobel L, Brock M, Löffler J, Ebel F. Characterization of Aspergillus terreus Accessory Conidia and Their Interactions With Murine Macrophages. Frontiers in microbiology. 2022:13():896145. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.896145. Epub 2022 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 35783442]

Gibbons JG, Rokas A. The function and evolution of the Aspergillus genome. Trends in microbiology. 2013 Jan:21(1):14-22. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2012.09.005. Epub 2012 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 23084572]

Kanj A, Abdallah N, Soubani AO. The spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Respiratory medicine. 2018 Aug:141():121-131. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.029. Epub 2018 Jul 3 [PubMed PMID: 30053957]

Montone KT. Pathology of Fungal Rhinosinusitis: A Review. Head and neck pathology. 2016 Mar:10(1):40-46. doi: 10.1007/s12105-016-0690-0. Epub 2016 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 26830404]

Thompson GR 3rd, Young JH. Aspergillus Infections. The New England journal of medicine. 2021 Oct 14:385(16):1496-1509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2027424. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34644473]

Denning DW. Aspergillosis: diagnosis and treatment. International journal of antimicrobial agents. 1996 Feb:6(3):161-8 [PubMed PMID: 18611704]

Lamoth F, Calandra T. Let's add invasive aspergillosis to the list of influenza complications. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2018 Oct:6(10):733-735. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30332-1. Epub 2018 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 30076120]

Hoenigl M, Gangneux JP, Segal E, Alanio A, Chakrabarti A, Chen SC, Govender N, Hagen F, Klimko N, Meis JF, Pasqualotto AC, Seidel D, Walsh TJ, Lagrou K, Lass-Flörl C, Cornely OA, European Confederation of Medical Mycology (ECMM). Global guidelines and initiatives from the European Confederation of Medical Mycology to improve patient care and research worldwide: New leadership is about working together. Mycoses. 2018 Nov:61(11):885-894. doi: 10.1111/myc.12836. Epub 2018 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 30086186]

Wéry N. Bioaerosols from composting facilities--a review. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2014:4():42. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00042. Epub 2014 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 24772393]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChakrabarti A, Chatterjee SS, Das A, Shivaprakash MR. Invasive aspergillosis in developing countries. Medical mycology. 2011 Apr:49 Suppl 1():S35-47. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.505206. Epub 2010 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 20718613]

Smith TC, Benefield RJ, Kim JH. Risk of Fungal Endophthalmitis Associated with Cataract Surgery: A Mini-Review. Mycopathologia. 2015 Dec:180(5-6):291-7. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9932-z. Epub 2015 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 26318595]

Sionov E, Sandovsky-Losica H, Gov Y, Segal E. Adherence of Aspergillus species to soft contact lenses and attempts to inhibit the adherence. Mycoses. 2001 Dec:44(11-12):464-71 [PubMed PMID: 11820259]

Manikandan P, Abdel-Hadi A, Randhir Babu Singh Y, Revathi R, Anita R, Banawas S, Bin Dukhyil AA, Alshehri B, Shobana CS, Panneer Selvam K, Narendran V. Fungal Keratitis: Epidemiology, Rapid Detection, and Antifungal Susceptibilities of Fusarium and Aspergillus Isolates from Corneal Scrapings. BioMed research international. 2019:2019():6395840. doi: 10.1155/2019/6395840. Epub 2019 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 30800674]

Koutserimpas C, Chamakioti I, Raptis K, Alpantaki K, Vrioni G, Samonis G. Osseous Infections Caused by Aspergillus Species. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Jan 14:12(1):. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12010201. Epub 2022 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 35054368]

Routray C, Nwaigwe C. Sternal osteomyelitis secondary to Aspergillus fumigatus after cardiothoracic surgery. Medical mycology case reports. 2020 Jun:28():16-19. doi: 10.1016/j.mmcr.2020.03.003. Epub 2020 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 32274324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDarr-Foit S, Schliemann S, Scholl S, Hipler UC, Elsner P. Primary cutaneous aspergillosis - an uncommon opportunistic infection Review of the literature and case presentation. Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft = Journal of the German Society of Dermatology : JDDG. 2017 Aug:15(8):839-841. doi: 10.1111/ddg.13297. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28763605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNorbury W, Herndon DN, Tanksley J, Jeschke MG, Finnerty CC. Infection in Burns. Surgical infections. 2016 Apr:17(2):250-5. doi: 10.1089/sur.2013.134. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26978531]

Bongomin F, Batac CR, Richardson MD, Denning DW. A Review of Onychomycosis Due to Aspergillus Species. Mycopathologia. 2018 Jun:183(3):485-493. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0222-9. Epub 2017 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 29147866]

Strickland AB, Shi M. Mechanisms of fungal dissemination. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2021 Apr:78(7):3219-3238. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03736-z. Epub 2021 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 33449153]

Valerio M, Camici M, Machado M, Galar A, Olmedo M, Sousa D, Antorrena-Miranda I, Fariñas MC, Hidalgo-Tenorio C, Montejo M, Vena A, Guinea J, Bouza E, Muñoz P, GAMES Study Group. Aspergillus endocarditis in the recent years, report of cases of a multicentric national cohort and literature review. Mycoses. 2022 Mar:65(3):362-373. doi: 10.1111/myc.13415. Epub 2022 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 34931375]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCeylan B, Yilmaz M, Beköz HS, Ramadan S, Ertan Akan G, Mert A. Primary gastrointestinal aspergillosis: a case report and literature review. Le infezioni in medicina. 2019 Mar 1:27(1):85-92 [PubMed PMID: 30882385]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKidd SE, Chen SC, Meyer W, Halliday CL. A New Age in Molecular Diagnostics for Invasive Fungal Disease: Are We Ready? Frontiers in microbiology. 2019:10():2903. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02903. Epub 2020 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31993022]

Abad A, Fernández-Molina JV, Bikandi J, Ramírez A, Margareto J, Sendino J, Hernando FL, Pontón J, Garaizar J, Rementeria A. What makes Aspergillus fumigatus a successful pathogen? Genes and molecules involved in invasive aspergillosis. Revista iberoamericana de micologia. 2010 Oct-Dec:27(4):155-82. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.10.003. Epub 2010 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 20974273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang Y, Zhang L, Zhou L, Zhang M, Xu Y. Epidemiology, Drug Susceptibility, and Clinical Risk Factors in Patients With Invasive Aspergillosis. Frontiers in public health. 2022:10():835092. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.835092. Epub 2022 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 35493371]

Khoo SH, Denning DW. Invasive aspergillosis in patients with AIDS. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1994 Aug:19 Suppl 1():S41-8 [PubMed PMID: 7948570]

van de Peppel RJ, Visser LG, Dekkers OM, de Boer MGJ. The burden of Invasive Aspergillosis in patients with haematological malignancy: A meta-analysis and systematic review. The Journal of infection. 2018 Jun:76(6):550-562. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.02.012. Epub 2018 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 29727605]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAbers MS, Ghebremichael MS, Timmons AK, Warren HS, Poznansky MC, Vyas JM. A Critical Reappraisal of Prolonged Neutropenia as a Risk Factor for Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Open forum infectious diseases. 2016 Jan:3(1):ofw036. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw036. Epub 2016 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 27006961]

Bassetti M, Bouza E. Invasive mould infections in the ICU setting: complexities and solutions. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2017 Mar 1:72(suppl_1):i39-i47. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx032. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28355466]

Morgan J, Wannemuehler KA, Marr KA, Hadley S, Kontoyiannis DP, Walsh TJ, Fridkin SK, Pappas PG, Warnock DW. Incidence of invasive aspergillosis following hematopoietic stem cell and solid organ transplantation: interim results of a prospective multicenter surveillance program. Medical mycology. 2005 May:43 Suppl 1():S49-58 [PubMed PMID: 16110792]

Jenks JD, Nam HH, Hoenigl M. Invasive aspergillosis in critically ill patients: Review of definitions and diagnostic approaches. Mycoses. 2021 Sep:64(9):1002-1014. doi: 10.1111/myc.13274. Epub 2021 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 33760284]

Robinson KM. Mechanistic Basis of Super-Infection: Influenza-Associated Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis. Journal of fungi (Basel, Switzerland). 2022 Apr 22:8(5):. doi: 10.3390/jof8050428. Epub 2022 Apr 22 [PubMed PMID: 35628684]

Bartoletti M, Pascale R, Cricca M, Rinaldi M, Maccaro A, Bussini L, Fornaro G, Tonetti T, Pizzilli G, Francalanci E, Giuntoli L, Rubin A, Moroni A, Ambretti S, Trapani F, Vatamanu O, Ranieri VM, Castelli A, Baiocchi M, Lewis R, Giannella M, Viale P, PREDICO Study Group. Epidemiology of Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis Among Intubated Patients With COVID-19: A Prospective Study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2021 Dec 6:73(11):e3606-e3614. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1065. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32719848]

Zilberberg MD, Harrington R, Spalding JR, Shorr AF. Burden of hospitalizations over time with invasive aspergillosis in the United States, 2004-2013. BMC public health. 2019 May 17:19(1):591. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6932-9. Epub 2019 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 31101036]

Niederwieser D, Baldomero H, Bazuaye N, Bupp C, Chaudhri N, Corbacioglu S, Elhaddad A, Frutos C, Galeano S, Hamad N, Hamidieh AA, Hashmi S, Ho A, Horowitz MM, Iida M, Jaimovich G, Karduss A, Kodera Y, Kröger N, Péffault de Latour R, Lee JW, Martínez-Rolón J, Pasquini MC, Passweg J, Paulson K, Seber A, Snowden JA, Srivastava A, Szer J, Weisdorf D, Worel N, Koh MBC, Aljurf M, Greinix H, Atsuta Y, Saber W. One and a half million hematopoietic stem cell transplants: continuous and differential improvement in worldwide access with the use of non-identical family donors. Haematologica. 2022 May 1:107(5):1045-1053. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2021.279189. Epub 2022 May 1 [PubMed PMID: 34382386]

Agarwal R, Sehgal IS, Dhooria S, Muthu V, Prasad KT, Bal A, Aggarwal AN, Chakrabarti A. Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis. The Indian journal of medical research. 2020 Jun:151(6):529-549. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1187_19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32719226]

Sabino R, Veríssimo C, Viegas C, Viegas S, Brandão J, Alves-Correia M, Borrego LM, Clemons KV, Stevens DA, Richardson M. The role of occupational Aspergillus exposure in the development of diseases. Medical mycology. 2019 Apr 1:57(Supplement_2):S196-S205. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy090. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30816970]

Benedict K, Thompson GR 3rd, Jackson BR. Cannabis Use and Fungal Infections in a Commercially Insured Population, United States, 2016. Emerging infectious diseases. 2020 Jun:26(6):1308-1310. doi: 10.3201/eid2606.191570. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32441624]

Zilberberg MD, Nathanson BH, Harrington R, Spalding JR, Shorr AF. Epidemiology and Outcomes of Hospitalizations With Invasive Aspergillosis in the United States, 2009-2013. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2018 Aug 16:67(5):727-735. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy181. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29718296]

Feldmesser M. Role of neutrophils in invasive aspergillosis. Infection and immunity. 2006 Dec:74(12):6514-6 [PubMed PMID: 17030575]

Alanio A, Bretagne S. Challenges in microbiological diagnosis of invasive Aspergillus infections. F1000Research. 2017:6():. pii: F1000 Faculty Rev-157. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.10216.1. Epub 2017 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 28299183]

Lass-Flörl C. How to make a fast diagnosis in invasive aspergillosis. Medical mycology. 2019 Apr 1:57(Supplement_2):S155-S160. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy103. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30816965]

Sugui JA, Kwon-Chung KJ, Juvvadi PR, Latgé JP, Steinbach WJ. Aspergillus fumigatus and related species. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2014 Nov 6:5(2):a019786. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a019786. Epub 2014 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 25377144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández-Cruz A, Magira E, Heo ST, Evans S, Tarrand J, Kontoyiannis DP. Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Cytology in Culture-Documented Invasive Pulmonary Aspergillosis in Patients with Hematologic Diseases: Analysis of 67 Episodes. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2018 Oct:56(10):. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00962-18. Epub 2018 Sep 25 [PubMed PMID: 30021823]

Gletsou E, Ioannou M, Liakopoulos V, Tsiambas E, Ragos V, Stefanidis I. Aspergillosis in immunocompromised patients with haematological malignancies. Journal of B.U.ON. : official journal of the Balkan Union of Oncology. 2018 Dec:23(7):7-10 [PubMed PMID: 30722105]

Fung M, Babik J, Humphreys IM, Davis GE. Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Invasive Fungal Sinusitis in Cancer and Transplant Patients. Current infectious disease reports. 2019 Nov 26:21(12):53. doi: 10.1007/s11908-019-0707-4. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31773398]

Howells RC, Ramadan HH. Usefulness of computed tomography and magnetic resonance in fulminant invasive fungal rhinosinusitis. American journal of rhinology. 2001 Jul-Aug:15(4):255-61 [PubMed PMID: 11554658]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePatterson TF, Thompson GR 3rd, Denning DW, Fishman JA, Hadley S, Herbrecht R, Kontoyiannis DP, Marr KA, Morrison VA, Nguyen MH, Segal BH, Steinbach WJ, Stevens DA, Walsh TJ, Wingard JR, Young JA, Bennett JE. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Aspergillosis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2016 Aug 15:63(4):e1-e60. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw326. Epub 2016 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 27365388]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSamanta P, Clancy CJ, Nguyen MH. Fungal infections in lung transplantation. Journal of thoracic disease. 2021 Nov:13(11):6695-6707. doi: 10.21037/jtd-2021-26. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34992845]

Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K, Lass-Flörl C, Lewis RE, Munoz P, Verweij PE, Warris A, Ader F, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Barnes RA, Beigelman-Aubry C, Blot S, Bouza E, Brüggemann RJM, Buchheidt D, Cadranel J, Castagnola E, Chakrabarti A, Cuenca-Estrella M, Dimopoulos G, Fortun J, Gangneux JP, Garbino J, Heinz WJ, Herbrecht R, Heussel CP, Kibbler CC, Klimko N, Kullberg BJ, Lange C, Lehrnbecher T, Löffler J, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Marchetti O, Meis JF, Pagano L, Ribaud P, Richardson M, Roilides E, Ruhnke M, Sanguinetti M, Sheppard DC, Sinkó J, Skiada A, Vehreschild MJGT, Viscoli C, Cornely OA. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clinical microbiology and infection : the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. 2018 May:24 Suppl 1():e1-e38. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.01.002. Epub 2018 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 29544767]

Maertens JA, Klont R, Masson C, Theunissen K, Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Heinen C, Crépin B, Van Eldere J, Tabouret M, Donnelly JP, Verweij PE. Optimization of the cutoff value for the Aspergillus double-sandwich enzyme immunoassay. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 May 15:44(10):1329-36 [PubMed PMID: 17443470]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceD'Haese J, Theunissen K, Vermeulen E, Schoemans H, De Vlieger G, Lammertijn L, Meersseman P, Meersseman W, Lagrou K, Maertens J. Detection of galactomannan in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid samples of patients at risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis: analytical and clinical validity. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2012 Apr:50(4):1258-63. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06423-11. Epub 2012 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 22301025]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOtting KA, Stover KR, Cleary JD. Drug-laboratory interaction between beta-lactam antibiotics and the galactomannan antigen test used to detect mould infections. The Brazilian journal of infectious diseases : an official publication of the Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases. 2014 Sep-Oct:18(5):544-7. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2014.03.009. Epub 2014 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 24833197]

Klingspor L, Loeffler J. Aspergillus PCR formidable challenges and progress. Medical mycology. 2009:47 Suppl 1():S241-7. doi: 10.1080/13693780802616823. Epub 2009 Feb 27 [PubMed PMID: 19253138]

Guo Y, Bai Y, Yang C, Gu L. Evaluation of Aspergillus IgG, IgM antibody for diagnosing in chronic pulmonary aspergillosis: A prospective study from a single center in China. Medicine. 2019 Apr:98(16):e15021. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000015021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31008929]

Mohedano Del Pozo RB, Rubio Alonso M, Cuétara García MS. Diagnosis of invasive fungal disease in hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Revista iberoamericana de micologia. 2018 Jul-Sep:35(3):117-122. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2017.07.004. Epub 2018 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 30078525]

Kamal YA. Black pleural effusion: etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Indian journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2019 Jul:35(3):485-492. doi: 10.1007/s12055-018-0756-6. Epub 2018 Nov 5 [PubMed PMID: 33061034]

Davda S, Kowa XY, Aziz Z, Ellis S, Cheasty E, Cappocci S, Balan A. The development of pulmonary aspergillosis and its histologic, clinical, and radiologic manifestations. Clinical radiology. 2018 Nov:73(11):913-921. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2018.06.017. Epub 2018 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 30075854]

Greene R. The radiological spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. Medical mycology. 2005 May:43 Suppl 1():S147-54 [PubMed PMID: 16110807]

Chabi ML, Goracci A, Roche N, Paugam A, Lupo A, Revel MP. Pulmonary aspergillosis. Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2015 May:96(5):435-42. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2015.01.005. Epub 2015 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 25753544]

Kosmidis C, Mackenzie A, Harris C, Hashad R, Lynch F, Denning DW. The incidence of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in patients receiving voriconazole therapy for chronic pulmonary aspergillosis. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology. 2020 Nov:393(11):2233-2237. doi: 10.1007/s00210-020-01950-x. Epub 2020 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 32820348]

Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Cadranel J, Flick H, Godet C, Hennequin C, Hoenigl M, Kosmidis C, Lange C, Munteanu O, Page I, Salzer HJF, on behalf of CPAnet. Treatment of Chronic Pulmonary Aspergillosis: Current Standards and Future Perspectives. Respiration; international review of thoracic diseases. 2018:96(2):159-170. doi: 10.1159/000489474. Epub 2018 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 29982245]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCornely OA, Koehler P, Arenz D, C Mellinghoff S. EQUAL Aspergillosis Score 2018: An ECMM score derived from current guidelines to measure QUALity of the clinical management of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycoses. 2018 Nov:61(11):833-836. doi: 10.1111/myc.12820. Epub 2018 Jul 13 [PubMed PMID: 29944740]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYun CH, Zhou W, Rui YW. [Classification and surgery of chronic pulmonary aspergillosis]. Zhonghua jie he he hu xi za zhi = Zhonghua jiehe he huxi zazhi = Chinese journal of tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2017 Oct 12:40(10):780-782. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2017.10.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29050136]

Herbrecht R, Denning DW, Patterson TF, Bennett JE, Greene RE, Oestmann JW, Kern WV, Marr KA, Ribaud P, Lortholary O, Sylvester R, Rubin RH, Wingard JR, Stark P, Durand C, Caillot D, Thiel E, Chandrasekar PH, Hodges MR, Schlamm HT, Troke PF, de Pauw B, Invasive Fungal Infections Group of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer and the Global Aspergillus Study Group. Voriconazole versus amphotericin B for primary therapy of invasive aspergillosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2002 Aug 8:347(6):408-15 [PubMed PMID: 12167683]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSam QH, Yew WS, Seneviratne CJ, Chang MW, Chai LYA. Immunomodulation as Therapy for Fungal Infection: Are We Closer? Frontiers in microbiology. 2018:9():1612. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01612. Epub 2018 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 30090091]

Kwon JC, Kim SH, Park SH, Choi SM, Lee DG, Choi JH, Yoo JH, Kim YJ, Lee S, Kim HJ, Lee JW, Min WS. Prognosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with hematologic diseases in Korea. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2012 Mar:72(3):284-92. doi: 10.4046/trd.2012.72.3.284. Epub 2012 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 23227068]

Ruhnke M, Kofla G, Otto K, Schwartz S. CNS aspergillosis: recognition, diagnosis and management. CNS drugs. 2007:21(8):659-76 [PubMed PMID: 17630818]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaddley JW, Andes DR, Marr KA, Kauffman CA, Kontoyiannis DP, Ito JI, Schuster MG, Brizendine KD, Patterson TF, Lyon GM, Boeckh M, Oster RA, Chiller T, Pappas PG. Antifungal therapy and length of hospitalization in transplant patients with invasive aspergillosis. Medical mycology. 2013 Feb:51(2):128-35. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.690108. Epub 2012 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 22680976]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBen-Ami R, Halaburda K, Klyasova G, Metan G, Torosian T, Akova M. A multidisciplinary team approach to the management of patients with suspected or diagnosed invasive fungal disease. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2013 Nov:68 Suppl 3():iii25-33. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt390. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24155143]