Introduction

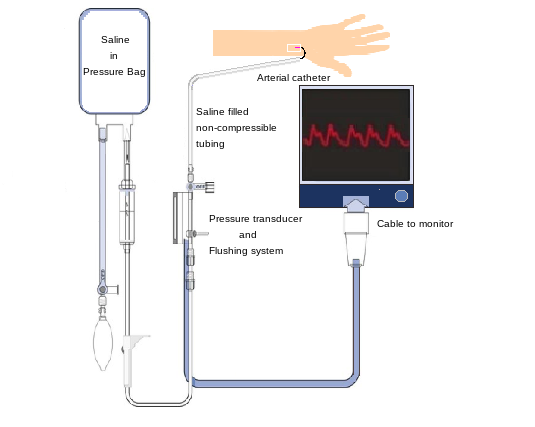

Hemodynamic monitoring is important in the care of any hospitalized patient. Frequent monitoring is of utmost importance in critically ill patients and surgical patients with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality. This can be achieved through intermittent monitoring, which is non-invasive but only provides snapshots in time, or by continuous invasive monitoring. The most common way to do this is arterial pressure monitoring via the cannulation of a peripheral artery. Each cardiac contraction exerts pressure, which results in mechanical motion of flow within the catheter. The mechanical motion is transmitted to a transducer via a rigid fluid-filled tubing. The transducer converts this information into electrical signals, which are transmitted to the monitor. The monitor displays a beat-to-beat arterial waveform as well as numerical pressures. This provides the care team with continuous information about the patient's cardiovascular system and can be used for diagnosis and treatment.[1][2][3][4][5]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The most common site of arterial cannulation is the radial artery due to ease of accessibility. Other sites are the brachial, femoral, and dorsalis pedis artery.[6][7]

Indications

For the following patient care scenarios, an arterial line would be indicated:[1][2][3][6]

- Critically ill patients in the ICU who require close monitoring of hemodynamics. In these patients, blood pressure measurements at spaced out intervals may be unsafe as they may have sudden changes in their hemodynamic status and require timely attention.

- Patients being treated with vasoactive medications. These patients benefit from arterial monitoring, allowing the clinician to safely titrate the medication to the desired blood pressure effect.

- Surgical patients are at increased risk of morbidity or mortality, either because of preexisting comorbidities (cardiac, pulmonary, anemia, etc.) or because of more complicated procedures. These include but are not limited to neurosurgical procedures, cardiopulmonary procedures, and procedures in which a large volume of blood loss is anticipated.

- Patients who require frequent lab draws. These include patients on prolonged mechanical ventilation, which necessitates an analysis of arterial blood gas for titration of vent settings. The ABG also allows for monitoring hemoglobin and hematocrit, treatment of electrolyte imbalances, and evaluating a patient's responsiveness to fluid resuscitation and administration of blood products and calcium. In these patients, the presence of an arterial line allows a clinician to easily obtain a sample of blood without having to stick the patient repeatedly. This minimizes patient discomfort and decreases the infection risk, as the integrity of the skin does not need to be violated with each lab draw.

Contraindications

While arterial blood pressure monitoring can provide invaluable information, arterial cannulation is not routine patient care. It is not required for every patient in the ICU or every patient undergoing surgery. For certain patients, the cannulation of an artery is contraindicated. These include infection at the site of insertion, an anatomic variant in which collateral circulation is absent or compromised, the presence of peripheral arterial vascular insufficiency, and peripheral arterial vascular diseases such as small to medium vessel arteritis. Additionally, while not absolute contraindications, careful consideration should be made in patients who have coagulopathies or take medications that prevent normal coagulation.[2][5][8]

Complications

Complications of arterial cannulation for blood pressure monitoring include:

- Infection

- Lack of collateral circulation resulting in vascular insufficiency

- Formation of a hematoma

- Formation of an arteriovenous (AV) fistula

- Stenosis of vessel

- Blood loss

There is controversy regarding the catheterization of the brachial artery. There are several reasons for this. One reason is its proximity to the median nerve; therefore, inadvertent injury to the median nerve is possible. Another concern for catheterization at the brachial artery is thrombosis. The third reason for concern is limb ischemia due to a lack of collateral vessels. However, rates of these complications are low, and catheterization at this site is associated with a lower risk of infection compared with femoral artery catheterization. In cardiac surgery patients, brachial artery catheterization is more reliable compared with radial artery catheterization. This is especially true after cardiopulmonary bypass. Therefore, due to the low risks associated with brachial artery catheterization, this site is a viable option for catheterization of the upper extremity.[2][3][9][10][11]

Clinical Significance

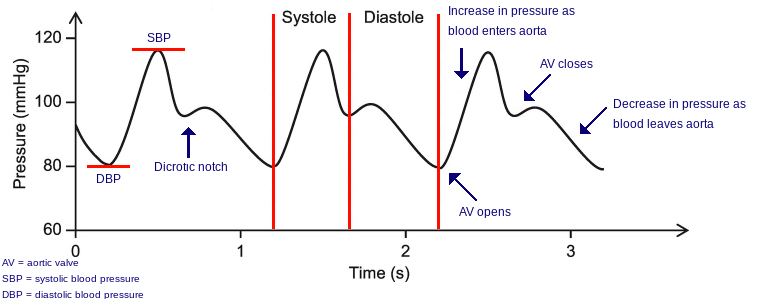

Arterial pressure monitors provide continuous information on a patient's hemodynamics. This information is invaluable to assist in timely clinical decision-making and intervention in the care of critically ill patients. Analysis of the arterial pressure wave can allow the clinician to understand the patient's heart function better as the arterial pressure wave corresponds with the cardiac cycle. During systole, the aortic valve opens, and blood from the left ventricle is rapidly ejected into the aorta. The arterial waveform will show an upswing followed by a downward turn. The closure of the aortic valve marks the beginning of diastole. The arterial waveform will show a notch on the downward stroke; this notch is called the dicrotic notch and is due to the closure of the aortic valve. The remainder of the downward stroke is the diastolic flow of blood into the arterial tree. A patient with abnormal heart rhythm or valvular abnormalities will have an abnormal arterial waveform.[1][3][12]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Arterial cannulation can provide invaluable information in the care of critically ill patients. However, it is not without risks, often overlooked as a significant patient care problem. Any time the integrity of the skin is violated, the risk of infection exists. This is especially true in procedures involving the placement of plastic cannulas into vessels where they may stay for extended periods. In the United States, an estimated 80,000 catheter-related bloodstream infections occur each year. While cannulation of a radial artery may not be as serious as cannulation of a major vessel like those in the neck or groin, both have the potential for catheter-related bloodstream infection, and this risk is not insignificant. This is especially true considering that the patient population in whom an arterial line is indicated are more likely to be critically ill and with multiple comorbidities. In these patients, a catheter-associated infection can be catastrophic. Therefore, it is vital that any time an arterial line is placed, meticulous care is taken to minimize infection during placement and for the duration of the time that the line is in situ. Multiple studies have been conducted to compare the rates of bloodstream infection between different intravascular devices. While the location of the catheter and duration of catheter placement affect infection rates, the resounding conclusion is that infection rates from arterial catheters are comparable to those of central venous catheters.[5][13][14][15] [Level 1]

Several guidelines exist to prevent intravascular catheter-related infections. One is available through the CDC. Emphasis is placed on choosing sites with lower rates of infection. This would be the radial, brachial, and dorsalis pedis in adults. In children, using the radial, dorsalis pedis, and posterior tibial arteries is more appropriate. Other points of emphasis are clinician attire of mask and cap, proper hand hygiene, adequate cleansing of patient skin, and placement of drapes to create a sterile field.

One aspect that cannot be overlooked is the importance of nursing care in managing catheter-associated infections. While nurses are typically not placing these catheters, they are at the front line when it comes to infection prevention. This is because they are usually the ones accessing the ports for lab draws in addition to performing dressing changes and routine skin care. Through proper education of nursing staff on how to maintain sterility of the arterial pressure monitoring circuit and continued care of the skin around the cannulation site, the infection rate associated with arterial catheters can be minimized.

Lastly, it should be everyone's responsibility to ensure that lines are not kept for longer than necessary, as there is a direct relationship between the duration of a line and the infection risk. There should be open communication between nursing staff and ICU providers to discuss removing any lines in place that are no longer required for patient care. When a patient no longer has an indication for arterial pressure monitoring, the catheter should be removed, and the area should be dressed to allow the cannulation site to heal.[16][17][18]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

To ensure that a patient receives optimal treatment, staff must be aware of factors that affect the safety and accuracy of arterial monitoring. This starts with training providers on proper technique for placement of the arterial line, including sterile technique and proper dressing of the line to minimize infection. This also includes training on the correct use and care of the equipment to obtain accurate data. The clinical utility of the pressure monitoring system depends on the accuracy of the data it provides. This accuracy is affected by several factors, which are covered below.[9][19]

To accurately measure arterial blood pressure, the system must be correctly set up. For patients who are lying down, the transducer is usually positioned at the level of the right atrium or the midaxillary line. For patients who are sitting, the cerebral pressure is less than at the level of the heart, so the transducer should be placed at the level of the brain.

The weight of the column of fluid within the tubing exerts hydrostatic pressure on the transducer, which can affect the blood pressure reading. Proper leveling of the transducer minimizes the effect of hydrostatic pressure on the transducer and ensures the accuracy of the measurement. For every 2.5 cm, the transducer is above or below the catheter level, and the pressure in the system changes by 1.877 mm. If the transducer is positioned too low relative to the catheter, the fluid within the tubing above the transducer exerts greater pressure on the transducer and produces an abnormally high pressure value. If the transducer is positioned too high relative to the catheter, the fluid within the tubing above the transducer exerts less pressure on the transducer and produces an abnormally low pressure value.

The measuring system must also be zeroed to obtain accurate data. Zeroing the system provides a reference point of pressure. Most commonly, this is atmospheric pressure. To zero the transducer, the stopcock is opened to the atmosphere. The "zero" button is pressed to indicate on the monitor that this is the zero reference pressure.

Thus, if the transducer is positioned too high, the readings will be lowered, and vice versa for a transducer that is positioned too low. This can be dangerous if healthcare providers are recording inaccurate measurements and making treatment decisions based on inaccurate data. Therefore, the correct positioning of the transducer is crucial for accurate blood pressure monitoring and patient care. The position of the transducer should be checked every time the OR or patient bed is repositioned.

Another factor that affects the accuracy of data is the damping of the system. This is the amount of resonance in the system and will affect the systolic and diastolic pressure while maintaining the correct mean arterial pressure. If the system has inadequate damping, there will be an excess of resonance, which will result in an overestimation of the systolic pressure and an underestimation of the diastolic pressure. If the system is overdamped, there will be a falsely low systolic pressure, but the diastolic pressure is usually accurate. Overdamping can be due to a clot or buildup of fibrin in the catheter tip. A system that is not optimally damped will be apparent on waveform analysis. An overdamped trace will show less than 1 1/2 oscillations below the baseline with an unclear dicrotic notch. And overdamped tracing will show oscillations both below and above the baseline, known as "ringing." An easy way to test the damping is to flush the system and assess the dynamic response. This is done by quickly flushing the system via the snap or pull tab. When this is activated, the monitor will display a square waveform that rises suddenly, flattens, and sharply declines. This will be followed by one or two oscillations appearing above and below the baseline after the release of the flush tab. This indicates an optimal dynamic response. A dicrotic notch should also be clearly present.[1][20]

The above steps will optimize the arterial pressure monitoring system to accurately reflect the patient's actual arterial pressure.

Media

References

Gardner RM. Direct blood pressure measurement--dynamic response requirements. Anesthesiology. 1981 Mar:54(3):227-36 [PubMed PMID: 7469106]

Frezza EE, Mezghebe H. Indications and complications of arterial catheter use in surgical or medical intensive care units: analysis of 4932 patients. The American surgeon. 1998 Feb:64(2):127-31 [PubMed PMID: 9486883]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceScheer B, Perel A, Pfeiffer UJ. Clinical review: complications and risk factors of peripheral arterial catheters used for haemodynamic monitoring in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine. Critical care (London, England). 2002 Jun:6(3):199-204 [PubMed PMID: 12133178]

Gershengorn HB, Garland A, Kramer A, Scales DC, Rubenfeld G, Wunsch H. Variation of arterial and central venous catheter use in United States intensive care units. Anesthesiology. 2014 Mar:120(3):650-64. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24424071]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGershengorn HB, Wunsch H, Scales DC, Zarychanski R, Rubenfeld G, Garland A. Association between arterial catheter use and hospital mortality in intensive care units. JAMA internal medicine. 2014 Nov:174(11):1746-54. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3297. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25201069]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKaki A, Blank N, Alraies MC, Kajy M, Grines CL, Hasan R, Htun WW, Glazier J, Mohamad T, Elder M, Schreiber T. Access and closure management of large bore femoral arterial access. Journal of interventional cardiology. 2018 Dec:31(6):969-977. doi: 10.1111/joic.12571. Epub 2018 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 30456854]

Nuttall G, Burckhardt J, Hadley A, Kane S, Kor D, Marienau MS, Schroeder DR, Handlogten K, Wilson G, Oliver WC. Surgical and Patient Risk Factors for Severe Arterial Line Complications in Adults. Anesthesiology. 2016 Mar:124(3):590-7. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000967. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26640979]

Paik JJ, Hirpara R, Heller JA, Hummers LK, Wigley FM, Shah AA. Thrombotic complications after radial arterial line placement in systemic sclerosis: A case series. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism. 2016 Oct:46(2):196-199. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.03.015. Epub 2016 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 27139167]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFranco-Sadud R, Schnobrich D, Mathews BK, Candotti C, Abdel-Ghani S, Perez MG, Rodgers SC, Mader MJ, Haro EK, Dancel R, Cho J, Grikis L, Lucas BP, SHM Point-of-care Ultrasound Task Force, Soni NJ. Recommendations on the Use of Ultrasound Guidance for Central and Peripheral Vascular Access in Adults: A Position Statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. Journal of hospital medicine. 2019 Sep:14(9):E1-E22. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3287. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31561287]

Chim H, Bakri K, Moran SL. Complications related to radial artery occlusion, radial artery harvest, and arterial lines. Hand clinics. 2015 Feb:31(1):93-100. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2014.09.010. Epub 2014 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 25455360]

Hignett R, Stephens R. Radial arterial lines. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2006 May:67(5):M86-8 [PubMed PMID: 16729631]

. . :(): [PubMed PMID: 32053524]

O'Horo JC, Maki DG, Krupp AE, Safdar N. Arterial catheters as a source of bloodstream infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Critical care medicine. 2014 Jun:42(6):1334-9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000166. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24413576]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKoh DB, Gowardman JR, Rickard CM, Robertson IK, Brown A. Prospective study of peripheral arterial catheter infection and comparison with concurrently sited central venous catheters. Critical care medicine. 2008 Feb:36(2):397-402. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318161f74b. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18216598]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaki DG, Kluger DM, Crnich CJ. The risk of bloodstream infection in adults with different intravascular devices: a systematic review of 200 published prospective studies. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2006 Sep:81(9):1159-71 [PubMed PMID: 16970212]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceO'Grady NP, Alexander M, Burns LA, Dellinger EP, Garland J, Heard SO, Lipsett PA, Masur H, Mermel LA, Pearson ML, Raad II, Randolph AG, Rupp ME, Saint S, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC). Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011 May:52(9):e162-93. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir257. Epub 2011 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 21460264]

Ruschulte H, Franke M, Gastmeier P, Zenz S, Mahr KH, Buchholz S, Hertenstein B, Hecker H, Piepenbrock S. Prevention of central venous catheter related infections with chlorhexidine gluconate impregnated wound dressings: a randomized controlled trial. Annals of hematology. 2009 Mar:88(3):267-72. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0568-7. Epub 2008 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 18679683]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHo KM, Litton E. Use of chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing to prevent vascular and epidural catheter colonization and infection: a meta-analysis. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy. 2006 Aug:58(2):281-7 [PubMed PMID: 16757502]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGrover S, Currier PF, Elinoff JM, Katz JT, McMahon GT. Improving residents' knowledge of arterial and central line placement with a web-based curriculum. Journal of graduate medical education. 2010 Dec:2(4):548-54. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00029.1. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22132276]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChee BC, Baldwin IC, Shahwan-Akl L, Fealy NG, Heland MJ, Rogan JJ. Evaluation of a radial artery cannulation training program for intensive care nurses: a descriptive, explorative study. Australian critical care : official journal of the Confederation of Australian Critical Care Nurses. 2011 May:24(2):117-25. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2010.12.003. Epub 2011 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 21211987]