Introduction

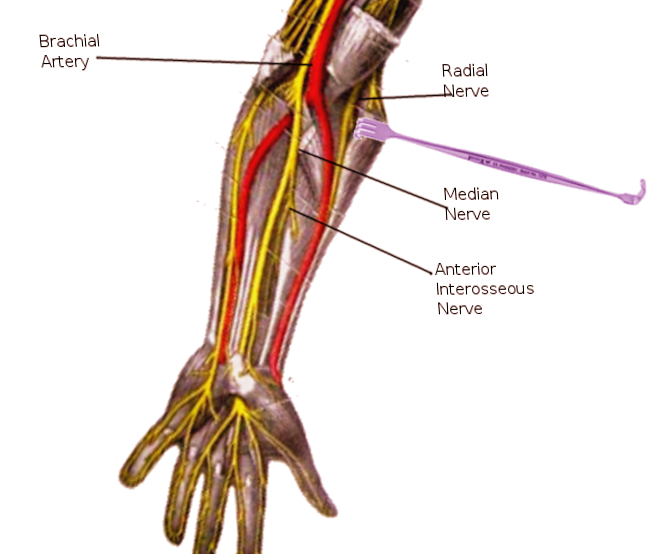

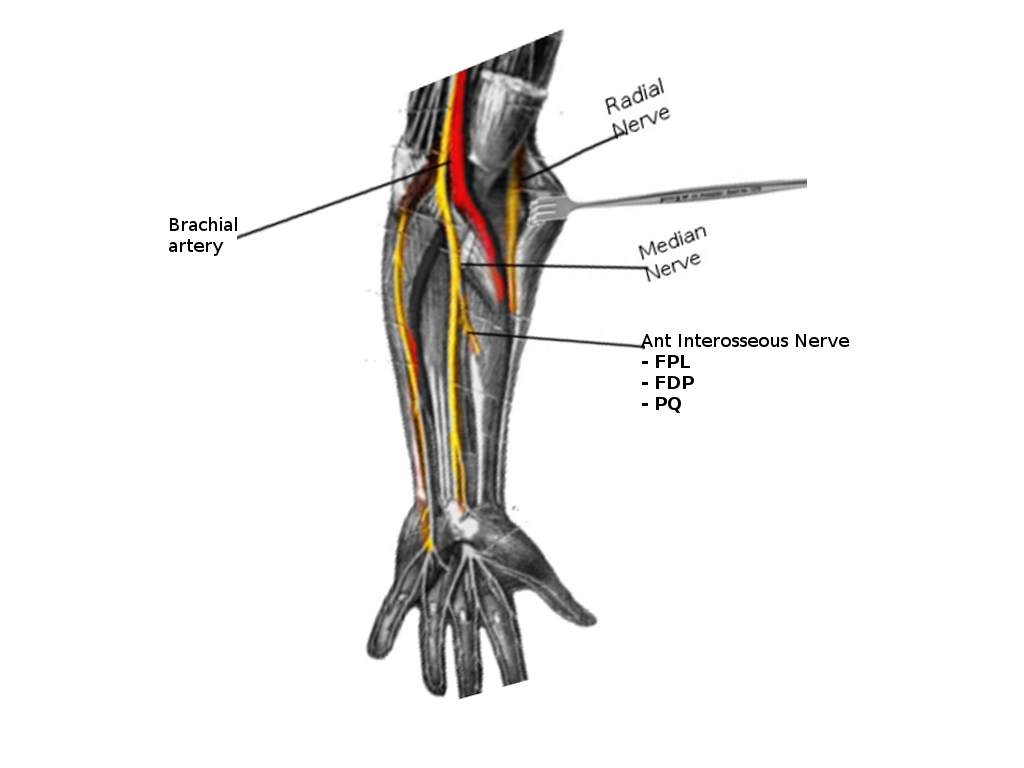

The anterior interosseous nerve (AIN) is the terminal motor branch of the median nerve. It branches from the median nerve in the proximal forearm between the two heads of the pronator teres muscle to run deep along the interosseous membrane. From proximal to distal, it innervates the flexor pollicus longus (FPL), the index and long fingers of the flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), and the pronator quadratus (PQ).[1] AIN syndrome is an isolated palsy of these three muscles. It manifests mostly as pain in the forearm accompanied frequently by a characteristic weakness of the index and thumb finger pincer movement. Many cases of AIN syndrome arise secondary to transient neuritis, although nerve compression and trauma are known etiologies as well. Different explanations have been proposed as the etiology of the disease. Controversy still exists among upper extremity surgeons about it; nevertheless, the condition is considered a neuritis in most cases.[2]

Parsonage and Turner first described the syndrome in 1948. Leslie Gordon Kiloh and Samuel Nevin defined it as an isolated lesion of the anterior interosseous nerve in 1952. Its old name was Kiloh-Nevin syndrome. Different methods of treatment with reasonable outcomes have been reported. Both surgical and medical interventions have been addressed with different timing and variable results.[3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Several causes of anterior interosseous nerve syndrome have been documented. Etiologies can be grouped as either spontaneous or traumatic.[4] Among the traumatic causes are forearm fractures such as supracondylar fractures, penetrating injuries and stab wounds, cast fixation, venipuncture, and complication of open reduction and internal fixation of fractures. Among the most common of the spontaneous causative factors are brachial plexus neuritis, compartment syndrome, and compression neuropathy.[5]

The most common site of AIN entrapment/compression is the tendinous edge of the deep head of the pronator teres muscle. Other potential sites include:

- The proximal edge of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) arch (the FDS arcade)

- Gantzer's muscle (accessory head of the FPL muscle)

- FDS or FDP accessory muscles

- Arterial thrombosis (radial or ulnar artery have been implicated)

- Lacertus fibrous

AIN syndrome should be clinically differentiating from stenosing tenosynovitis or pathologies limited to local pathology affecting the flexor tendons alone (i.e., flexor tendon adhesions or partial versus complete flexor tendon rupture). The nerve is even normally compressed by the fibrous bands that often originate from the deep head of the brachialis fascia and the pronator teres, and this pressure can increase with minor variations.[6]

Differential diagnosis of the condition consists of a non-compressive neuropathy like brachial neuritis, which might mimic anterior interosseous nerve neuropathy. An FPL tendon rupture is also a possibility among patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. To exclude the differential diagnosis, the wrist must be flexed passively and extended to confirm that the individual has an intact tenodesis effect.[7] Rheumatoid disease and gouty arthritis may be predisposing factors in anterior interosseous nerve entrapment.

Epidemiology

This disease is rare, comprising only 1% of all upper extremity palsies

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology can occur secondary to primary entrapment, direct trauma, or in more ambiguous or vague clinical presentations, the condition manifests following vial neuritis. Very similar syndromes can be caused by more proximal lesions, such as brachial plexus neuritis. In the latter, clinicians should have a heightened diagnostic suspicion in patients presenting with motor loss following prodromal symptoms consisting of intense shoulder pain or recent viral illness/exposure.

History and Physical

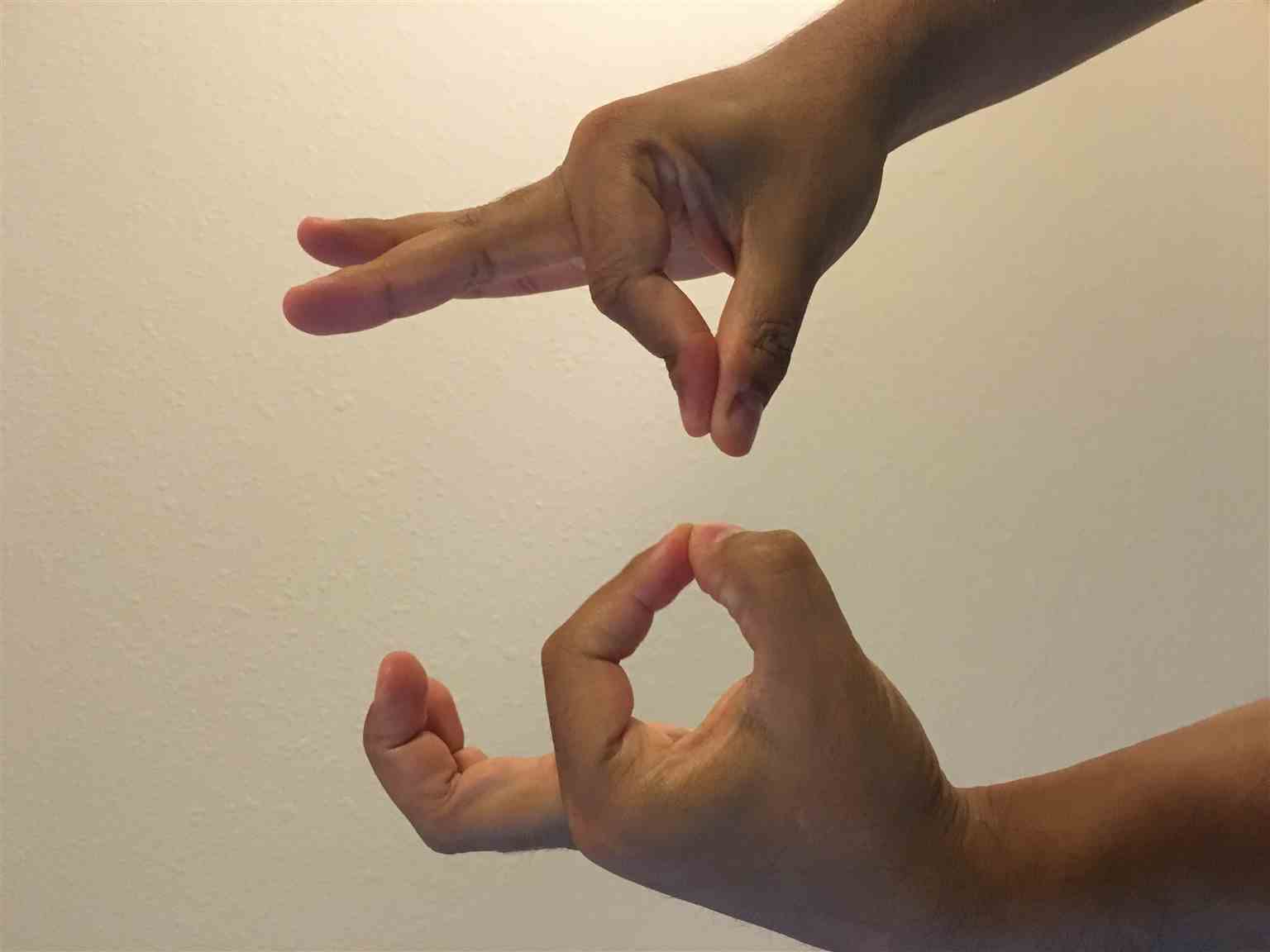

True AIN syndrome presentation will present with motor deficits only. No sensory changes should be appreciated. Most patients experience poorly localized pain in the forearm and cubital fossa. This pain is usually the primary complaint. There are no sensations of numbness, tingling, or sensory deficits. The patient will complain of having difficulty bringing the distal phalanx of the thumb and index finger together. On a physical exam, the pinch grip test would turn positive; rather than making the "OK" sign, the patient will clap the sheet between the index finger and an extended thumb. The patient may also complain of having difficulty forming a fist or the inability to button their shirts. Sensation should be spared on the exam.[8][9]

Evaluation

Electrodiagnostic studies are instrumental for anterior interosseous nerve syndrome of spontaneous etiology. Sensory nerve conduction studies of the median nerve should be normal as there is no sensory innervation to the anterior interosseous nerve. Electromyography will show findings in the flexor pollicus longus, the radial portion of the flexor digitorum profundus, and the pronator quadratus. These will be helpful in differentiating neurologic amyotrophy from compression neuropathy.[10] Magnetic resonance imaging is also useful in the evaluation of these patients.

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative modalities

The general consensus for managing AIN syndrome includes a period of rest, observation, and splinting of the elbow near 90 degrees of flexion (or position of most comfort for the patient). The majority of patients will experience improvement between 6 and 12 weeks of activity modification.

Other modalities to consider include NSAIDs and physical therapy modalities (including pain modalities and massage techniques if tolerated)

Surgical decompression

Surgical treatment consists of exploration, neurolysis, and decompression after several months of failed nonoperative modalities. The literature reports 75% or greater positive outcomes following surgery, with higher rates reported in patients with an identifiable, clear space-occupying mass.

Unless a clear cause is identified, surgical intervention is typically offered only in select cases, and the option is discussed following at least three months of failed conservative treatment.[11][12](B3)

During median nerve surgical decompression, meticulous dissection is necessary to establish exact sites of compression. It is critical in the identification and release of compressing edges or fibrous bands.

Differential Diagnosis

Anterior interosseous nerve entrapment or compression injury remains a challenging clinical diagnosis. It is difficult because it is mainly a motor nerve and the syndrome is often mistaken for a ligamentous finger injury. Differential diagnosis includes stenosing tenosynovitis, flexor tendon adherence or adhesion, flexor tendon rupture, and brachial neuritis. Brachial plexus neuritis can cause very similar syndromes.[6][7]

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Anterior interosseous nerve studies are usually retrospective. No randomized controlled trials have been performed, partially since the condition is relatively rare. Patients who have undergone surgery have good post operation records; many patients will resolve with conservative treatment. Therefore, the natural history of the disease seems to be benign. Those retrospective studies have shown the surgical and nonsurgical methods to be equivocal.[7]

Prognosis

The prognosis is usually good, and most cases don't require surgical treatment. If conservative therapy fails beyond three months, surgery might be offered in select cases.

Complications

Complications include those of the disease process that caused the syndrome or those of the surgery intended to treat it.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Even though anterior interosseous nerve syndrome is very rare, clinical suspicion ought to arise in the presence of the radial flexor digitorum profundus and weak flexor pollicis longus muscles. The utilization of electrodiagnostic studies, coupled with MRI, is poised to assist in the diagnosis of anterior interosseous syndrome and help to specify the possible etiology.

Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome's optimal treatment has not yet been established. It is recommended that surgical interventions be offered only to those patients who do not demonstrate any clinical improvement during the first few months or to those with confirmed cases of compression neuropathy. Meticulous dissection is necessary during median nerve surgical decompression to establish sites of compression. It is critical in the identification and release of any other compressing edges or fibrous bands.[13]

An interprofessional approach to treatment is ideal. This approach includes primary care providers who encounter the disease first and electrophysiologists who run the nerve and muscle studies. It also includes orthopedic surgeons who follow the course of treatment, pharmacists who provide the medication needed, and physical therapists who perform the rehabilitation. Other healthcare team personnel such as the nursing staff should also assist in the coordinated care of the patient. This will result in the best outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aljawder A, Faqi MK, Mohamed A, Alkhalifa F. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome diagnosis and intraoperative findings: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2016:21():44-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.02.021. Epub 2016 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 26921536]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTyszkiewicz T, Atroshi I. Bilateral anterior interosseous nerve syndrome with 6-year interval. SAGE open medical case reports. 2018:6():2050313X18777416. doi: 10.1177/2050313X18777416. Epub 2018 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 29796273]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRodner CM, Tinsley BA, O'Malley MP. Pronator syndrome and anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2013 May:21(5):268-75. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-21-05-268. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23637145]

Komaru Y, Inokuchi R. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome. QJM : monthly journal of the Association of Physicians. 2017 Apr 1:110(4):243. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcw227. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28073933]

Xing SG, Tang JB. Entrapment neuropathy of the wrist, forearm, and elbow. Clinics in plastic surgery. 2014 Jul:41(3):561-88. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2014.03.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24996472]

Ochi K, Horiuchi Y, Tazaki K, Takayama S, Matsumura T. Fascicular constrictions in patients with spontaneous palsy of the anterior interosseous nerve and the posterior interosseous nerve. Journal of plastic surgery and hand surgery. 2012 Feb:46(1):19-24. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2011.634558. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22455572]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePark IJ, Roh YT, Jeong C, Kim HM. Spontaneous anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: clinical analysis of eleven surgical cases. Journal of plastic surgery and hand surgery. 2013 Dec:47(6):519-23. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2013.791624. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23627594]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEl Domiaty MA, Zoair MM, Sheta AA. The prevalence of accessory heads of the flexor pollicis longus and the flexor digitorum profundus muscles in Egyptians and their relations to median and anterior interosseous nerves. Folia morphologica. 2008 Feb:67(1):63-71 [PubMed PMID: 18335416]

Flores LP. Distal anterior interosseous nerve transfer to the deep ulnar nerve and end-to-side suture of the superficial ulnar nerve to the third common palmar digital nerve for treatment of high ulnar nerve injuries: experience in five cases. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria. 2011 Jun:69(3):519-24 [PubMed PMID: 21755133]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePham M, Bäumer P, Meinck HM, Schiefer J, Weiler M, Bendszus M, Kele H. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome: fascicular motor lesions of median nerve trunk. Neurology. 2014 Feb 18:82(7):598-606. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000128. Epub 2014 Jan 10 [PubMed PMID: 24415574]

Strohl AB, Zelouf DS. Ulnar Tunnel Syndrome, Radial Tunnel Syndrome, Anterior Interosseous Nerve Syndrome, and Pronator Syndrome. Instructional course lectures. 2017 Feb 15:66():153-162 [PubMed PMID: 28594495]

Sisco M, Dumanian GA. Anterior interosseous nerve syndrome following shoulder arthroscopy. A report of three cases. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2007 Feb:89(2):392-5 [PubMed PMID: 17272456]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchulte-Mattler WJ, Grimm T. [Common and not so common nerve entrapment syndromes: diagnostics, clinical aspects and therapy]. Der Nervenarzt. 2015 Feb:86(2):133-41. doi: 10.1007/s00115-014-4123-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25526716]