Introduction

The term amaurosis fugax is often used interchangeably to describe transient visual loss (TVL). However, it is employed widely in medicine to refer to any cause of transient monocular visual loss. Here, we will refer to amaurosis fugax only in the context of transient monocular visual loss associated with vascular thromboembolic events arising from the internal carotid arterial system. [1],[2],[3]

The condition is not common in children and more likely to have a benign cause. In adults, in most cases, the cause is atherosclerotic emboli from the carotid artery bifurcation.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

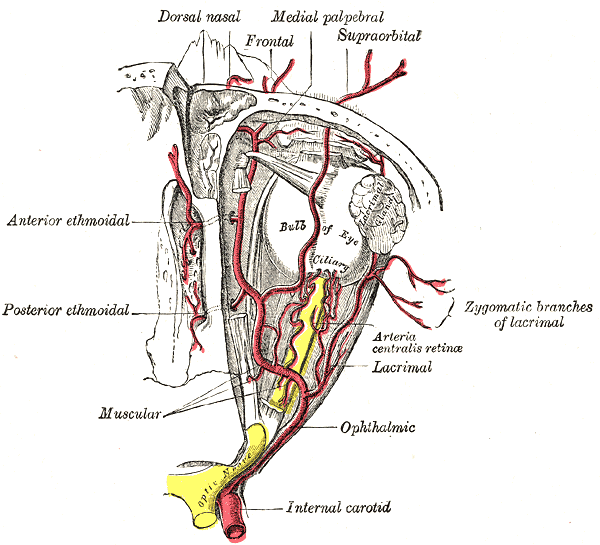

Amaurosis fugax is a result of an occlusion or stenosis of the internal carotid artery circulation. Thromboembolism originating from the carotid circulation, as well as hypoperfusion caused by the stenosis of this circulation, are the underlying mechanisms. The ocular ischemic syndrome results from chronic hypoperfusion due to unilateral or bilateral carotid artery occlusion. [3]

Epidemiology

Amaurosis fugax usually occurs in patients over the age of 50 who have other vascular risk factors which include hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, previous episodes of transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and claudication. The risk of hemispheric stroke in patients with amaurosis fugax is estimated to be 2% per year and 3% per year for those presenting with retinal emboli.

Risk factors for amaurosis fugax include:

- Diabetes

- Heart disease

- Smoking

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidemia

- Advanced age

- Use of cocaine

Pathophysiology

Amaurosis fugax may occur due to the following:

- Thromboembolism from a carotid plaque

- Hypoperfusion

- Vasospasm

- Elevated plasma viscosity, for example with leukemia, multiple myeloma

- Atherosclerotic cerebrovascular disease

In amaurosis fugax, the loss of vision is usually unilateral, painless and transient. In most cases, the vision loss may vary from a few seconds to a few minutes. The embolus in most cases is from an atherosclerotic plaque in the carotid bifurcation. Hypoperfusion from any cause can also mimic amaurosis fugax.

Histopathology

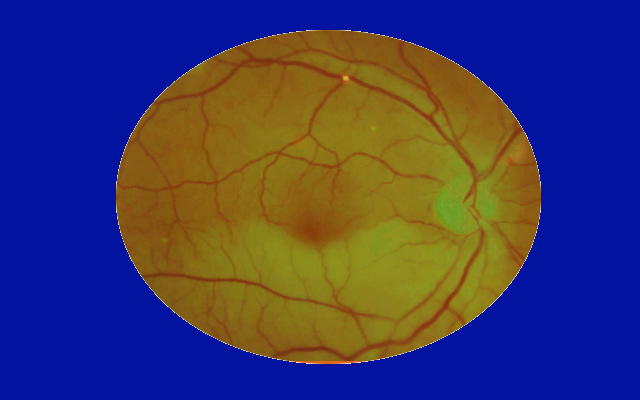

During the retinal examination, the health care provider may see the cholesterol plaque lodged within a retinal vessel. It is known as a Hollenhorst plaque, and the cholesterol particle appears refractile, yellow, and bright. [4]

History and Physical

Patients complain of sudden monocular vision loss that can last between 2 to 30 minutes. The vision loss can involve the entire visual field or can be partial. Patients often describe it as a "curtain coming down” in front of their eye or as a generalized darkening or shadow. These episodes spontaneously resolve. Patients can experience 1 or multiple episodes. In anyone over the age of 60 experiencing multiple episodes, giant cell arteritis should be suspected, and further investigations should be undertaken.

Some patients can present with signs of intraretinal emboli, such as cholesterol plaques (Hollenhorst plaques). Depending on the extent of the resulting retinal ischemia, central retinal artery occlusion or branch retinal artery occlusion can develop.

In some patients, particularly those with the ocular ischemic syndrome, exposure to bright lights can provoke the episodes, as the ipsilateral severe internal carotid occlusion causes hypoperfusion of the retinal circulation and the resulting vascular insufficiency of the retinal photoreceptors combined with increased metabolic demand leads to blurred or decreased vision in those patients. Vision usually returns to normal once the photoreceptors have completely hyperpolarized.

Patients with ocular ischemic syndrome typically present with blurred vision that can be transient. The visual acuity declines with the progression of the disease. The affected eye shows episcleral injection and, on slit-lamp examination, minimal anterior chamber inflammation is present. Intraocular pressure can be low or normal due to the decreased perfusion of the ciliary body which is responsible for aqueous production. The fundus examination usually demonstrates dilated and tortuous retinal veins with narrowed arterioles accompanied by mid-peripheral dot-and-blot retinal hemorrhages. With persistent hypoperfusion, ischemia progresses and manifests as neovascularization of the iris, anterior chamber angle, retina, and optic disc. Ocular pain is a hallmark of the disease and is usually alleviated in the supine position. The latter is a result of ischemia of the ocular and orbital branches of the trigeminal nerve. [5]

Evaluation

Assessment of vascular risk factors is most important in anyone presenting with symptoms of amaurosis fugax. Patients should be assessed for hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, cardiac disease and asked about tobacco use. A careful physical examination, including full ophthalmological examination with a dilated fundus examination, as well as auscultation of the carotid arteries and the heart, should be performed. Blood work, including a complete blood count, blood glucose level, lipid profile, prothrombin time and partial thromboplastin time, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein should be ordered as well. [6],[7]

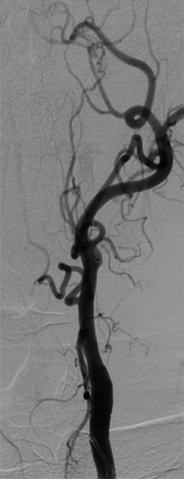

Carotid Doppler is a non-invasive test used to assess the extracranial and intracranial status of the vessels. Magnetic resonance angiography and computed tomography angiography can also be used to evaluate the patency of the internal carotid arteries.

An electrocardiogram, as well as Holter monitoring, and, in some cases, transesophageal echocardiography, should be obtained to rule out any possible source of rhythmic disturbance or cardiac emboli.

Neuroimaging studies are almost always done to rule out other causes of vision loss. In addition, the CT scan can help rule out a hemorrhagic lesion in the brain.

Treatment / Management

Treatment is first aimed at controlling and treating the underlying vascular risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.

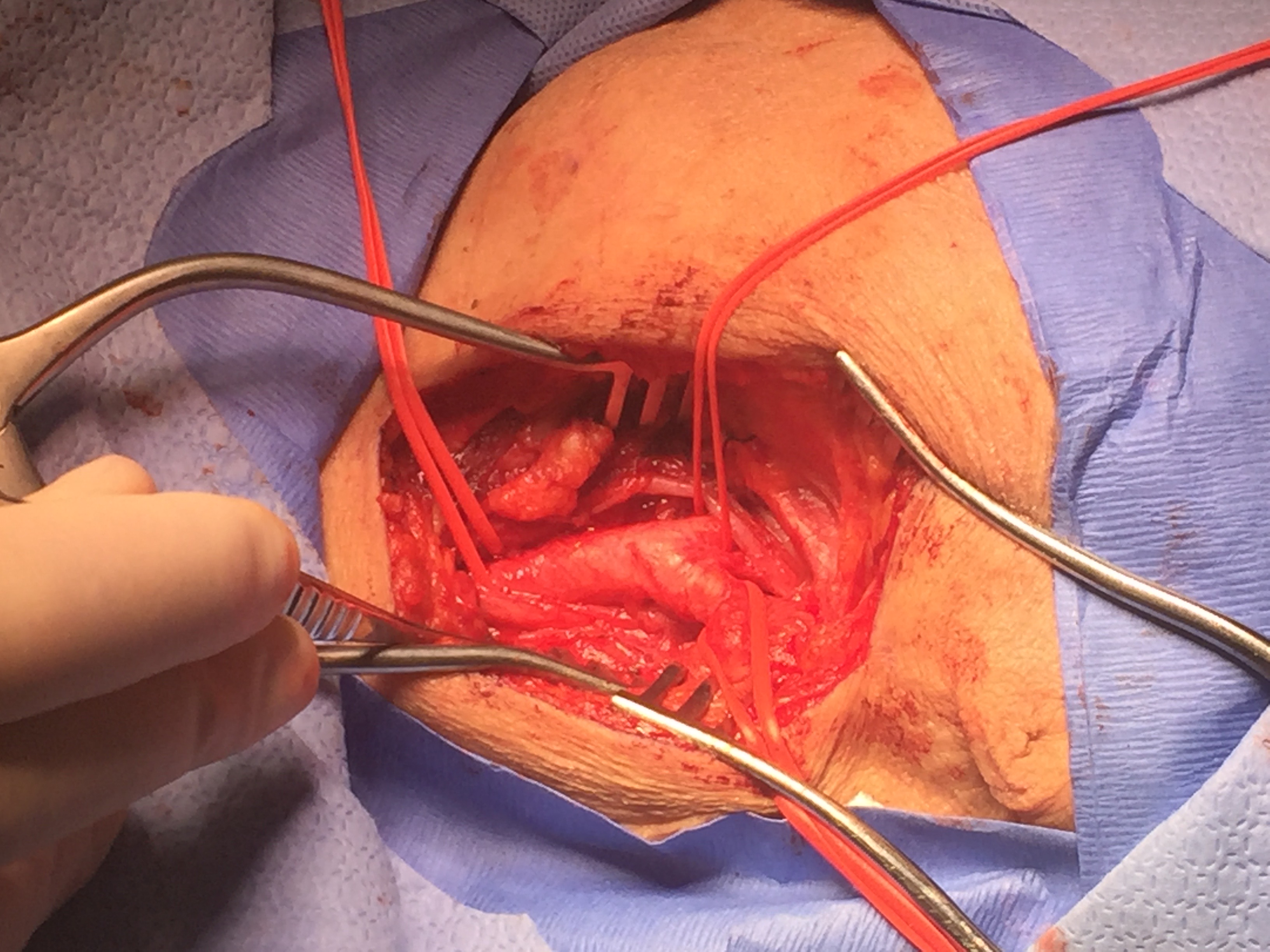

Two large studies, the North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial (NASCET) and the European Carotid Surgery Trial (ECST) found that endarterectomy in symptomatic patients who have carotid stenosis greater than 70% reduces future risks of stroke. However, these studies did not address ocular TIAs separately. The NASCET further compared patients with hemispheric TIAs and ocular TIAs demonstrating that patients with hemispheric TIAs had a 2-year stroke incidence of about 44% compared to about 17% in ocular TIAs. The patients with ocular TIAs did not experience a major stroke episode, which was defined as a functional deficit persisting for more than 90 days. Both groups also had similar grades of carotid stenosis (about 83%). [2],[8],[9]

Therefore, the clinician needs to address if the risks of death and preoperative stroke in patients undergoing endarterectomy outweigh the low risk of observing these specific patients and treating them with anticoagulants alone, such as aspirin, warfarin or clopidogrel.

It is important to note that both NASCET and ECST evaluated open endarterectomy but, since then, carotid stenting has become commonly used. Carotid stenting is comparable to endarterectomy, regarding treatment, and has similar low risks of death, stroke and myocardial infarction in patients with asymptomatic severe carotid artery stenosis. [10]

Treatment of ocular ischemic syndrome involves reducing the oxygen drive to the eye to decrease the neovascularization. This involves panretinal photocoagulation or intravitreal injections of anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of unilateral vision loss includes the following:

- Central retinal artery/vein occlusion

- Giant cell arteritis

- Multiple sclerosis

- Papilledema

- Epilepsy

- Sickle cell anemia

Prognosis

If amaurosis fugax is not diagnosed or treated, the patient risks a major stroke in the future. Most untreated patients with significant carotid artery plaques will develop a major stroke within 12 months. Those who undergo carotid endarterectomy have a good prognosis but the risk of adverse cardiac events still remains. Patients who do suffer a stroke have a guarded prognosis.

Complications

The main complications of amaurosis fugax include:

- Stroke

- Death

- Adverse cardiac events

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Amaurosis fugax is a harbinger of an imminent stroke. The first study of choice is an ultrasound to determine the presence of carotid artery stenosis. When an individual has been diagnosed with amaurosis fugax, it is vital to refer the patient first to a neurologist to confirm the diagnosis and examine for any other neurological deficits. Since many of these patients are smokers and diabetics and may have hypertension, they need a thorough presurgical workup to ensure that they can undergo general or local anesthesia. The time to undergo carotid endarterectomy is variable but expert opinion states that it should be within 4 to 8 weeks. [11],[12] (Level C)

While awaiting surgery, the nurse should educate the patient and the family on the dangers of smoking and the importance of blood pressure control. The pharmacist should make sure that the patient is on aspirin and compliant with his blood pressure and diabetes medications. Before surgery, the patient should be advised to stop all blood thinners.

An interdisciplinary team approach to patient care and education will lead to better outcomes. [Level 5]

Outcomes

There is a large amount of evidence to show that treating patients with amaurosis fugax can prevent a full-blown stroke. However, the treatment of carotid stenosis is in a state of flux. The condition can also be managed with angioplasty and stenting. For patients who are unfit for surgery or those who are asymptomatic, the endovascular approach may be viable, but symptomatic patients need an open procedure. There still remains debate as to which procedure is safer and the data is mixed and confusing because of the heterogeneity of the patients. The most important thing is to ensure that a patient with amaurosis fugax gets the appropriate referral to a neurologist first to confirm the diagnosis. The choice between a vascular or an endovascular procedure depends on personal preference. Both are safe procedures, and both have a role in the treatment of this serious disorder. [13],[14] (Level III) Whatever choice one makes, the person doing the procedure must be experienced, and have the support of an interprofessional team to achieve optimal outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

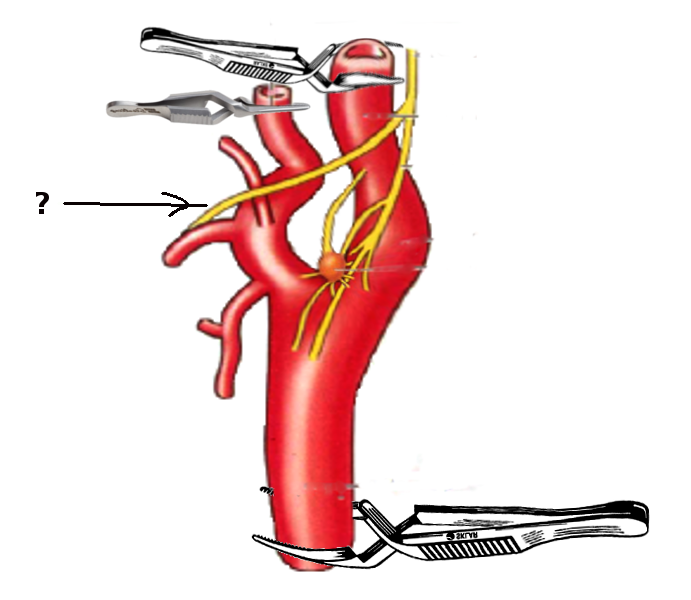

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Pula JH, Yuen CA. Eyes and stroke: the visual aspects of cerebrovascular disease. Stroke and vascular neurology. 2017 Dec:2(4):210-220. doi: 10.1136/svn-2017-000079. Epub 2017 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 29507782]

Qaja E, Theetha Kariyanna P. Carotid Artery Surgery. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722976]

Makhkamova DК. [Etiopathogenesis of ocular ischemic syndrome]. Vestnik oftalmologii. 2017:133(2):120-124. doi: 10.17116/oftalma20171332120-124. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28524151]

McCullough HK, Reinert CG, Hynan LS, Albiston CL, Inman MH, Boyd PI, Welborn MB 3rd, Clagett GP, Modrall JG. Ocular findings as predictors of carotid artery occlusive disease: is carotid imaging justified? Journal of vascular surgery. 2004 Aug:40(2):279-86 [PubMed PMID: 15297821]

Kvickström P, Lindblom B, Bergström G, Zetterberg M. Amaurosis fugax: risk factors and prevalence of significant carotid stenosis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2016:10():2165-2170 [PubMed PMID: 27826182]

Hagiwara Y, Shimizu T, Hasegawa Y. Contrast-enhanced transoral carotid ultrasonography for the diagnosis and follow-up of extracranial internal carotid artery dissection: A case report. Journal of clinical ultrasound : JCU. 2018 Jun:46(5):368-371. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22542. Epub 2017 Oct 9 [PubMed PMID: 28990690]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePula JH, Kwan K, Yuen CA, Kattah JC. Update on the evaluation of transient vision loss. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2016:10():297-303. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S94971. Epub 2016 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 26929593]

Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. OCULAR ARTERIAL OCCLUSIVE DISORDERS AND CAROTID ARTERY DISEASE. Ophthalmology. Retina. 2017 Jan-Feb:1(1):12-18. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2016.08.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28547004]

McBride R, Porter J, Al-Khaffaf H. The modified operative technique of partial eversion carotid endarterectomy. Journal of vascular surgery. 2017 Jan:65(1):263-266. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2016.10.057. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28010865]

Pribán V, Fiedler J, Chlouba V. [Ocular symptoms as an indication for carotid endarterectomy]. Ceska a slovenska oftalmologie : casopis Ceske oftalmologicke spolecnosti a Slovenske oftalmologicke spolecnosti. 2006 Sep:62(5):354-9 [PubMed PMID: 17039923]

Reid TD, Finney LJ, Hedges AR. The National Stroke Strategy - is it achievable? Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2009 Nov:91(8):641-4. doi: 10.1308/003588409X432491. Epub 2009 Aug 14 [PubMed PMID: 19686616]

Meyer D, Karreman E, Kopriva D. Factors associated with delay in carotid endarterectomy for patients with symptomatic severe internal carotid artery stenosis: a case-control study. CMAJ open. 2018 May 15:6(2):E211-E217. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20170060. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29769180]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePothof AB, Zwanenburg ES, Deery SE, O'Donnell TFX, de Borst GJ, Schermerhorn ML. An update on the incidence of perioperative outcomes after carotid endarterectomy, stratified by type of preprocedural neurologic symptom. Journal of vascular surgery. 2018 Mar:67(3):785-792. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.07.132. Epub 2017 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 29074118]

Cheng I, Vyas KS, Velaga S, Davenport DL, Saha SP. Outcomes of Carotid Endarterectomy with Primary Closure. The International journal of angiology : official publication of the International College of Angiology, Inc. 2017 Jun:26(2):83-88. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601053. Epub 2017 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 28566933]