Introduction

To be skillful at airway management, the provider must know the critical anatomical, physiological, and pathological features related to the airway. They should also be aware of the various tools and methods that have been developed for this purpose. It is additionally important to know the indications, contraindications, and complications of endotracheal intubation. It is vital to understand how to assess the confirmation of proper endotracheal tube placement. Additionally, knowing the differences between the adult, pediatric, and neonatal airways and being well versed with difficult airways is vital as these can significantly impact safe and effective airway control.[1]

The four principals of airway management in Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support are:

- Is the airway patent?

- Is the advanced airway indicated?

- Is the proper placement of the airway device confirmed?

- Is the tube secure, and is the placement of the tube confirmed frequently?

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The pediatric airway is narrowest at the subglottis (as opposed to the adult airway, where the glottis is the narrowest point) and is located cephalad and more anterior when compared to the adult airway. Children 12 years or younger have a smaller cricothyroid membrane, and their larynx is more compliant, funnel-shaped, and rostral in position. The larger occiput combined with a shorter neck makes laryngoscopy relatively more difficult, providing obstacles to the alignment of the oral, laryngeal, and tracheal axes. It often requires a folded towel or shoulder roll to achieve a neutral position of the neck and open the airway.[1] Proper positioning of any airway is vital for successful intubation, and it is important to know differences when compared to the adult patient.

The dimensions of the trachea depend on the age and sex of the child. Please see Table 1. There are different formulas to select the proper size of the ET tube.

- The Cole formula for uncuffed tubes: ID (internal diameter) in mm= (age in years)/4 + 4 (F)

- The Motoyama formula for cuffed ETTs in children aged 2 years or older: ID in mm = (age in years)/4 + 3.5 (EK)

- The Khine formula for cuffed ETTs in children younger than 2 years: ID in mm = (age in years)/4 + 3.0

For children aged 1 month to 6 years, ultrasound measurement of subglottic airway diameter better predicted appropriately sized endotracheal tube than traditional formulas using age and height. This may not be practical in an urgent or emergent situation, so familiarity with the airway sizing algorithms above is paramount.[2] Cuffed ET tubes are preferable to decrease the air leak, pressure necrosis in ventilated patients, as the incidence of laryngospasm may be higher with uncuffed ET tubes in prolonged intubation. These advantages must be weighed against the relatively larger diameter of the cuffed tube, which may trigger laryngospasm during intubation. Video-assisted laryngoscopy equipment is a more recent adjuvant in airway management that facilitates effective visualization of the airway.[3]

Table 1: Tracheal Dimensions ages 14 to 20 Years.[4]

Indications

Indications for intubation to secure the airway include respiratory failure (hypoxic or hypercapnic), apnea, a reduced level of consciousness (sometimes stated as GCS less than or equal to 8), rapid change of mental status, airway injury or impending airway compromise, high risk for aspiration, or 'trauma to the box (larynx),' which includes all penetrating injuries to the neck, abdomen, or chest.

Contraindications

Contraindications to endotracheal intubation include severe airway trauma or obstruction that does not permit the safe placement of an endotracheal tube. If an endotracheal tube cannot be placed, but an airway needs to be secured, a surgical airway is indicated. In an adult, a cricothyrotomy or needle cricothyrotomy is an emergent option; this should be converted to a formal tracheostomy as soon as an airway is established. An emergent tracheostomy (sometimes termed a "slash tracheostomy") is also an acceptable option. For a pediatric patient in whom an endotracheal tube cannot be placed, cricothyrotomy is not often performed and an emergent tracheostomy is preferred. The only absolute contraindication to surgical cricothyroidotomy is the age of the child. The exact age at which they can safely perform a surgical cricothyrotomy is controversial and not well defined and may depend more on the size and body habitus of the patient, as opposed to an absolute age. Various sources list lower age limits ranging from 5 years to 12 years, and Pediatric Advanced Life Support defines the pediatric airway as age 1 to 8 years. For a pediatric patient, a needle cricothyrotomy with trans-tracheal ventilation should be performed instead of an incision-based surgical cricothyrotomy. This should then be converted to a formal tracheostomy.

Equipment

Airway Position and Clearance

Upper airway obstruction can be relieved by head tilt, chin lift, or jaw thrust. In infants and children, a simple suctioning of the airway will help with the clearance. The bulb syringe or any other mechanical suction device can clear mucus or other debris from the airway. When using a bulb syringe to suction an infant, it is important to suction the mouth before the nose to avoid aspiration. The first step is to depress the bulb syringe and then place it in the mouth, then the nose. Infants are prone to vagal stimulation, and suctioning can lead to bradycardia. Suction must not last for over 10 seconds.

Adjuvants to Upper Airway Obstruction

Oropharyngeal airway: One cannot use an oropharyngeal airway in patients with a severe gag reflex or oral trauma, as it could stimulate this gag reflex and lead to aspiration of gastric contents. Different sized oral appliances are available. They are measured and sized from the lip to the angle of the jaw and are useful for patients with spontaneous respirations who need help to keep their airway open (sleep apnea patients, for example).

Nasopharyngeal airway: This is used in patients with an intact gag reflex, trismus, or oral trauma, or those who have undergone oral or oropharyngeal surgery where the oral cavity should not be instrumented. The important factor in sizing a nasopharyngeal airway (NPA) is not only the tube's width (which may be dictated by nostril aperture diameter or nasal septal and turbinate position) but also the stature of the subject. The average adult male needs a size 7 port, and the average female needs a size 6 port. A tall male requires size 8, and a tall female requires size 7, as the patient's vertical height roughly corresponds to the anteroposterior length of the midface, and thus, nasal cavity.[5]

A study of 413 infants under 12 months found an association between subject height and nares-vocal cord distance. To place the NPA in infants, the insertion length must, therefore, be slightly less than the anthropometric measurement of nose tip-earlobe distance.[6]

Bag-mask Ventilation

A properly performed mask ventilation is the fundamental maneuver in airway management. Both in adults and children, there are one- and two-hand techniques. For neonatal airway, one hand technique is usually effective, as a single hand can often perform all necessary maneuvers. One can relieve the upper airway obstruction encountered during simple mask ventilation via head tilt, chin lift, jaw thrust, and the application of continuous positive airway pressure. Bag-mask ventilation is also appropriate while preparing to intubate.

Advanced Airway

Examples are supraglottic devices (laryngeal mask airway, laryngeal tube, esophageal-tracheal) and endotracheal tube.

Laryngeal mask airway: A relatively recent advancement is the development of the supraglottic airway. Many devices exist. Two of the more popular supra-glottic devices, the classic laryngeal mask airway (LMA) and pro-seal LMA, have good data in the pediatric population to support their safety and efficacy. We recommend using a manometer to gauge the inflation pressure of the cuff of the LMA. Children with a recent upper respiratory infection have an increased incidence of respiratory complications with the use of LMA as compared to healthy children. In the pre-hospital setting, they often use supraglottic devices such as the King tube instead of an endotracheal tube because of the ease and speed with which it can be deployed. This facilitates the rapid establishment of a more secure airway, particularly in an emergent setting where emergency medical technicians or other personnel may be establishing a pediatric airway and may not be as comfortable in doing so.

Esophageal-Tracheal tube and Endotracheal Intubation

This is a supraglottic airway device now frequently used by many emergency medical personnel that intentionally intubates the esophagus, but the design of the device allows ventilation via a two-cuffed system and a ported tube. They are popular because of their ease of administration. They come in different sizes, but their routine use does not routinely extend to pediatric airway management.

Oxygen

Oxygen is a critical component of airway management. Pre-oxygenation with nasal cannulae, bi-valve mask, high flow oxygen, or bi-pap before the intubation can deliver the much-needed oxygen prior to intubation attempt.

Bougie

Some physicians consider the Bougie, which is a long, semi-rigid plastic device (a plastic stylet) as an adjunct or rescue device in difficult intubations, or as a part of the primary intubation algorithm.

Personnel

Ideally, at least two additional staff members should be available to assist the primary physician performing the intubation. They can help with the administration of medications, bagging the patient, and monitoring the patient. The team typically should include a physician, respiratory therapist, nurse, nursing technician, paramedic, or advanced practice provider.

Preparation

After pre-oxygenation with cricoid pressure and in-line cervical stabilization, rapid-sequence induction, followed by direct laryngoscopy (DL), is the safest and most effective approach.

The four D’s of the Difficult Airway

- Distortion

- Disproportion

- Dysmobility

- Dentition

The location of the vallecula is vital for all healthcare workers who perform intubation. It is an important anatomical landmark during oral intubation of the trachea. To visualize the posterior pharynx, one can utilize the Macintosh blade or the Miller blade. To visualize the vallecula using the curved Macintosh laryngoscope, place it over the tongue, moving towards the vallecula and depressing to see the glottis following the tongue. Subsequently, pull the glottis upwards to visualize the vocal cords, allowing placement of the endotracheal tube. Non-visualization of the vallecula during intubation increases the risk of esophageal intubation. If the clinician utilizes the Miller laryngoscope, which is a straight blade instead of curved, they place this straight blade past the vallecula directly over the epiglottis to visualize the vocal cords and place the endotracheal tube. Introduce the ET tube only after visualization of the glottis, followed by visualization of the vocal cords. Additionally, there is a frequently utilized alternative to the direct laryngoscopes for intubation, which includes a camera. This is utilized similarly to the straight or curved blade but uses a camera attached to a curved blade placed near the vallecular space allowing visualization of the vocal cords and place the ET tube. Regardless of the instrument used, if the clinician cannot identify any laryngeal structures on the initial attempt at visualization, slowly withdraw the blade until the larynx or epiglottis drops into view, then reassess the clinician position.

Required Equipment

- Laryngoscope

- Carbon dioxide detectors

- Continuous waveform capnography

- Medications: Sedatives and Paralytic agents for rapid sequence intubation (RSI)

- Material to fix the tube in place

- Chest X-ray

Following are the dosages of RSI medications:

Sedatives Used for Induction

- Etomidate: 0.3 to 0.4 mg/kg

- Fentanyl: 2 to 10 mcg/kg

- Midazolam: 0.1 to 0.3 mg/kg

- Propofol: 1 to 2.5 mg/kg

- Thiopental 3 to 5 mg/kg

Paralytic Agents

- Succinylcholine: 1 to 2 mg/kg

- Rocuronium 0.6 to 1.2 mg/kg

- Vecuronium 0.15 to 0.25 mg/kg

Technique or Treatment

The technique for intubation includes pre-oxygenation, administration of rapid sequence medications, application of cricoid pressure, and in-line cervical stabilization followed by laryngoscopy (direct or indirect). It is the safest and most effective approach.

The gold standard for assessing an ET placement is direct visualization with the help of a laryngoscope. Additional ways to assure proper confirmation of endotracheal tube placement include end-tidal carbon dioxide measurement, capnography waveform, chest X-ray, ultrasound, and clinical assessment. The American Heart Association recommends continuous waveform capnography besides clinical assessment as the most reliable method of confirming and monitoring the correct placement of an ET tube. Bedside mobile ultrasound is another resource that some emergency departments have to confirm the position of the ET tube. Many clinicians frequently use a chest X-ray to assess the placement of the ET tube. The optimum position of the ET tube is 2 centimeters above the carina. Complications of endotracheal intubation can include esophageal intubation or right mainstem intubation. When blind endotracheal intubation takes place, the tube may go down the right mainstem bronchus. One could reposition the tube if abnormal tube placement is seen in an X-ray or if a flat capnography waveform is noted and 0 mm Hg in the documented value, as 35 to 45 mm Hg is the expected normal range for appropriate endotracheal tube placement. Clinically, abnormal tube placement can be diagnosed with absent breath sounds on the left chest if right mainstem intubation has occurred, and no breath sounds will be heard bilaterally if abnormal esophageal intubation has occurred. Additionally, with esophageal intubation, air may be auscultated in the mid epigastric region upon ventilation administration. Lastly, low oxygen saturation will be noted. Once appropriate confirmation of the endotracheal tube is noted, it is essential to secure the ETT properly to assure it is not dislodged. Then continuous monitoring with waveform capnography and pulse oxygen monitor is performed.

Pediatric Intensive care specialists prefer to use a cuffed endotracheal tube instead of an uncuffed endotracheal tube to prevent air-leak.

Airway Management in Traumatic Patients

Trauma is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, especially for people aged 15 to 50. Trauma is the second-most common single cause of death, representing 8% of all deaths. The World Health Organization estimates that traumatic injuries from traffic accidents, drowning, poisoning, falls, burns, and violence kill over five million people worldwide annually, with millions more suffering from the consequences of injuries.

Rapid evacuation and transportation to a trauma center improve the outcome of severely injured patients. Prehospital intubation is controversial in the EMS literature. The medical director of an EMS service will dictate the clinical context in which he/she will allow a paramedic to intubate in the field. The EMS service monitors and transports these patients quickly and safely to the nearest trauma facility.

Surgical Airway

The age of the child is the only absolute contraindication to surgical cricothyroidotomy. The exact age at which they can safely perform a surgical cricothyrotomy is controversial and not well defined. Various sources list lower age limits ranging from 5 to 12 years, and Pediatric Advanced Life Support defines the pediatric airway as age 1 to 8 years.

Complications

Complications with intubation involve failure to secure the airway, esophageal intubation, hypoxic or hypercapnic respiratory failure leading to arrest, injury to oropharyngeal or laryngeal airway including bleeding, soft tissue swelling, injury to vocal cords.

When intubating a patient who suffered injuries to the chest, pay attention to the complications that could arise after the intubation, like tension pneumothorax or air leak from a bronchial injury. Patients with pneumothorax should have a chest tube before the intubation. In cases of bronchial injury, intubation can precipitate a massive air leak. Sometimes the physicians occlude a segment of the damaged lung with a bronchial blocker to avoid air escape.

Clinical Significance

Teaching points:

- Knowing the differences between pediatric airway and adult airway

- Knowing and selecting correct airway management strategies.

- Knowing the indications, technique, and medications used in rapid sequence intubation

- Knowing how to assess a difficult airway

- Knowing the alternate techniques to achieve a definitive airway

- Knowing the various adjuvants in the airway management

- Knowing the airway management in special circumstances like penetrating trauma

- Knowing the importance of training and practice in the pediatric airway for prehospital personnel.

- Knowing the indications, contraindications, and complications of endotracheal intubation.

- Knowing how to confirm successful endotracheal tube placement.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team approach, consisting of clinicians, mid-level practitioners (PAs and NPs), nursing, and emergency medical staff, employing good preparation, preoxygenation, and recognizing difficult airway enhances airway management success. Changing the plan once the provider recognizes the difficulty is prudent and safe. This decreases the failed intubation rates and improves patient outcomes.

All the personnel involved should regularly sharpen their skills either in the field or in the simulation lab. Proper training of the personnel played a bigger role in improving the success rates of intubation, the decrease in mortality rate than the field of medicine they specialized in.[7] [Level 3]

Emergency physicians use either length or weight-based estimation to select the correct endotracheal tube for intubation.[8] [Level 3]

For difficult airways, a camera-based laryngoscopy is better than the direct laryngoscope for the first pass success of the intubation.[9] [Level 1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

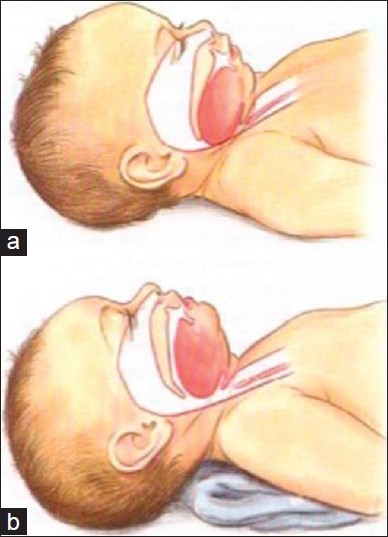

Figure 1: Artistic rendering of infant airway. (a) In image a note the large occiput which has caused flexion of the head and subsequently caused the base of the tongue to obstruct the upper airway. This obstruction has been relieved (b) by placing a towel under the shoulders and neck allowing more extension of the head and an opening of the upper airway

Contributed by Harless J, Ramaiah R, Bhananker SM. Pediatric airway management. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci [serial online] 2014 [cited 2017 Dec 3];4:65-70. Available from: http://www.ijciis.org/text.asp?2014/4/1/65/128015

References

Harless J, Ramaiah R, Bhananker SM. Pediatric airway management. International journal of critical illness and injury science. 2014 Jan:4(1):65-70. doi: 10.4103/2229-5151.128015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24741500]

Shibasaki M, Nakajima Y, Ishii S, Shimizu F, Shime N, Sessler DI. Prediction of pediatric endotracheal tube size by ultrasonography. Anesthesiology. 2010 Oct:113(4):819-24. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181ef6757. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20808208]

Newth CJ, Rachman B, Patel N, Hammer J. The use of cuffed versus uncuffed endotracheal tubes in pediatric intensive care. The Journal of pediatrics. 2004 Mar:144(3):333-7 [PubMed PMID: 15001938]

Griscom NT, Wohl ME. Dimensions of the growing trachea related to age and gender. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1986 Feb:146(2):233-7 [PubMed PMID: 3484568]

Roberts K, Whalley H, Bleetman A. The nasopharyngeal airway: dispelling myths and establishing the facts. Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 2005 Jun:22(6):394-6 [PubMed PMID: 15911941]

Shen CM, Soong WJ, Jeng MJ, Lee YS, Cheng CY, Sun J, Hwang B. Nasopharyngeal tract length measurement in infants. Acta paediatrica Taiwanica = Taiwan er ke yi xue hui za zhi. 2002 Mar-Apr:43(2):82-5 [PubMed PMID: 12041622]

Davis DP, Koprowicz KM, Newgard CD, Daya M, Bulger EM, Stiell I, Nichol G, Stephens S, Dreyer J, Minei J, Kerby JD. The relationship between out-of-hospital airway management and outcome among trauma patients with Glasgow Coma Scale Scores of 8 or less. Prehospital emergency care. 2011 Apr-Jun:15(2):184-92. doi: 10.3109/10903127.2010.545473. Epub 2011 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 21309705]

Daugherty RJ,Nadkarni V,Brenn BR, Endotracheal tube size estimation for children with pathological short stature. Pediatric emergency care. 2006 Nov [PubMed PMID: 17110862]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMosier JM, Stolz U, Chiu S, Sakles JC. Difficult airway management in the emergency department: GlideScope videolaryngoscopy compared to direct laryngoscopy. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012 Jun:42(6):629-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.007. Epub 2011 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 21911279]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence