Summary / Explanation

The 2022 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) guidelines on aortic diseases were developed by a multidisciplinary team including representatives from the ACC, AHA, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Surgery. The summary of the key recommendations from the guidelines is outlined below.[1][2]

Introduction

Ascending aortic dilation is defined as an aortic diameter of ≥4.0 cm, and the risk of aortic dissection significantly increases when the aortic diameter is ≥4.5 cm. Normalized aortic diameters are based on patient height, body surface area, or a cross-sectional aortic area-to-height ratio to define surgical thresholds in patients who are either shorter or taller than average. Acute aortic syndromes include aortic dissection, intramural hematoma, and penetrating aortic ulcer.

Aortic Dissection Classifications

-

The DeBakey classification describes aortic dissections as follows:

- Type I: Originates in the ascending aorta and extends to the arch and descending aorta

- Type II: Limited to the ascending aorta

- Type IIIa: Limited to the descending aorta

- Type IIIb: Originates in the descending aorta and extends to the distal branches

-

The Stanford classification divides aortic dissections into:

- Type A: Involves the ascending aorta

- Type B: Does not involve the ascending aorta

Newer data suggest that excessive elongation of the ascending aorta is predictive of dissection and is a potentially relevant measurement.[3]

Endovascular grafting is associated with endoleaks, which are classified as follows:

- Type Ia: Proximal attachment site endoleak

- Type Ib: Distal attachment site endoleak

- Type II: Backfilling of the aneurysm sac through branch vessels of the aorta

- Type III: Gaft defect or component misalignment

- Type IV: Graft wall leakage

- Type V: Endotension due to the aortic pressure transmitted through the graft to the aneurysm sac [4]

Imaging And Measurements

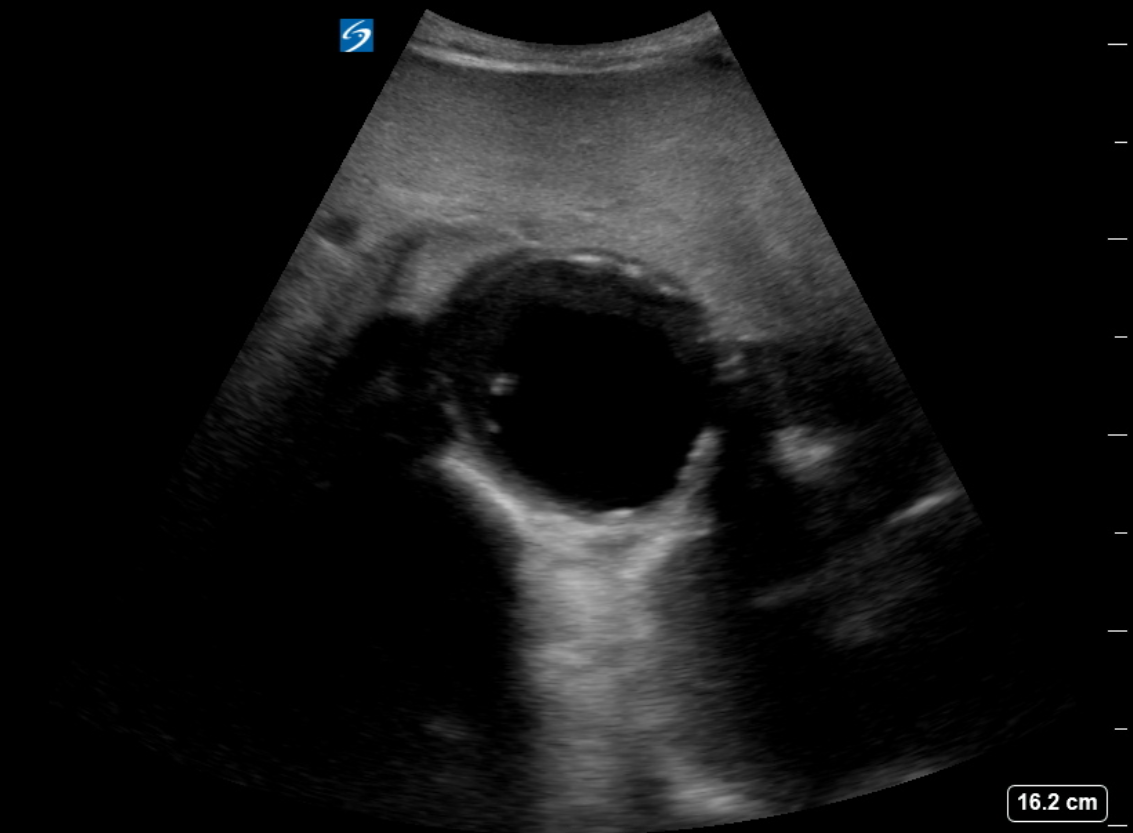

To maintain reproducibility, aortic measurements during surveillance need to be consistent. In addition, clinicians should reduce ionizing radiation exposure to patients who undergo surveillance imaging. Using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), aortic root measurements are captured during end-diastole from the anterior wall's leading edge to the posterior wall's leading edge. Using computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), aortic root measurements and ascending aortic dimensions should be taken from the inner edge to the inner edge using electrocardiographic gating. In addition, aortic root dimensions should be measured multiple times from sinus to sinus to obtain the maximum diameter. All men and women aged 65 or older who have ever smoked or have first-degree relatives diagnosed with abdominal aortic aneurysm should undergo an abdominal ultrasound to screen for abdominal aortic aneurysm (see Image. Ultrasound of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm). Surveillance imaging for thoracic aortic aneurysm and abdominal aortic aneurysm is performed based on the aortic diameters and growth rate (see Image. Measurement of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm). Gated chest CT is the first-line imaging modality to assess acute aortic syndrome.

Family Screening

A multigenerational family history is indicated for patients with aortic root or ascending aorta aneurysms or aortic dissection. Patients at risk for hereditary thoracic aortic disease should undergo genetic testing for known aortopathy genes. For patients with aneurysms of the aortic root or ascending aorta or those with aortic dissection, screening of first-degree relatives with aortic imaging is recommended. If patients are identified with a pathogenic variant for thoracic aortic disease, first-degree relatives should be offered genetic testing and cascade testing is indicated for the family members. For patients with a bicuspid aortic valve and a dilated aortic root, screening of all first-degree relatives with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), CT, or MRI is recommended.

Aortic Disease in Special Populations

- Surgical thresholds for prophylactic surgery in nonsyndromic heritable thoracic aortic disease are based on the genetic variant and additional risk factors for dissection, such as age, family history, and aortic diameter. For instance, patients with ACTA2 can experience aortic dissection at diameters <4.5 cm, and PRKG1-related variants can present in their late teens with type A or B dissection.

- All patients with Marfan syndrome should undergo TTE at diagnosis to measure aortic root and ascending aortic diameters, followed by another TTE 6 months later to monitor the growth rate. The evaluation should be followed by annual surveillance imaging with TTE, CT, or MRI.

- Patients with Marfan syndrome should be treated with a maximally tolerated β-blocker or an angiotensin receptor blocker to reduce the rate of aortic dilation.

- For patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome, a screening TTE should be performed to measure aortic root and ascending aortic diameters, followed by another TTE 6 months later to monitor the growth rate. Annual surveillance imaging with TTE, CT, or MRI is indicated.

- For patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome, a CT or MRI from head to pelvis should be performed to screen the entire aorta and its branches for aneurysms, dilation, or tortuosity.

- For patients with Turner syndrome, a screening TTE and MRI should be performed upon diagnosis to detect aortic dilation, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, and other congenital heart defects. Follow-up imaging is indicated every 5 years in children and every 10 years in adults.

- Women with aortopathy are at risk for aortic dissection during pregnancy. Aortic surveillance imaging throughout pregnancy and several weeks postpartum is indicated. Due to increased blood volume, heart rate, stroke volume, cardiac output, and neurohormonal activation that progress during pregnancy, most dissections related to pregnancy occur in the third trimester and in the first 12 weeks postpartum. Peripartum management should involve a multidisciplinary team with cardiothoracic surgery available for urgent intervention.

- Imaging is recommended before a planned pregnancy in women at risk for aortic disease, and imaging should be more frequent when comorbidities include aortic dilation, bicuspid aortic valve, aortic coarctation, and hypertension. Annual imaging is appropriate for patients older than 15 with an aortic size index >2.3 cm/m2.

Surgical Thresholds

- For sporadic and bicuspid aortic valve-related aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms, the appropriate thresholds for surgical intervention are ≥5.5 cm at most centers and ≥5.0 cm at experienced centers with a multidisciplinary aortic team.

- For sporadic aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms, surgical intervention should be considered for rapid growth, defined as a rate of growth ≥0.3 cm/year in 2 consecutive years or ≥0.5 cm/year in 1 year and ≥0.3 cm in 1 year for those with heritable thoracic aortic disease or bicuspid aortic valve.

- In patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement or repair with aortic root dilation, surgical ascending aortic replacement is reasonable for ascending aortic diameters of ≥5.0 cm or ≥4.5 cm at experienced centers.

- For asymptomatic patients with heritable thoracic aortic disease and Marfan syndrome–related aortic root and ascending aortic aneurysms, appropriate thresholds for surgical intervention are ≥5.0 cm at most centers and ≥4.5 cm, with a high risk of aortic dissection, at experienced centers with a multidisciplinary aortic team. Indications for earlier surgery include rapid growth (≥0.3 cm/year), family history of dissection, desire for pregnancy, severe valve regurgitation, and patient preference.

- For patients with Loeys-Dietz syndrome, the threshold for surgical intervention depends on various factors, including the genetic variant, aortic diameter, growth rate, age, sex, and family history. Surgery may be recommended at smaller aortic diameters for TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 variants when associated high-risk characteristics, such as women, small body size, severe extra-aortic features, family history, and aortic growth rate, are present.

- For asymptomatic patients aged 15 or older with Turner syndrome and at risk of aortic dissection, the threshold for surgical intervention is >2.5 cm/m2.

- For patients with descending thoracoabdominal aneurysms, the threshold for surgical intervention is ≥6 cm. In contrast, for abdominal aortic aneurysms, the threshold for surgical intervention is ≥5.5 cm for men and ≥5.0 cm for women.

- Aortic diameters vary with age, sex, height, and body size. Aortic event rates increase with aortic size indexed to height or body size. Prophylactic surgery is reasonable when the maximal cross-sectional area (cm2) of the root or ascending divided by height (m) is ≥10 cm2/m.

- Vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome leads to spontaneous aortic and arterial dissections at a young age, the onset and severity of which correlate with the pathogenic variant. The frequency of screening with imaging is uncertain, as vascular rupture or dissection may occur without significant dilation. β-Blockers have a potential benefit. Rapid arterial growth or dissection are indications for treatment, but no data are available to guide diameter thresholds for prophylactic intervention.

Medical Therapy

β-Blockers and angiotensin receptor blockers can be used as antihypertensives for patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm and hypertension. Low-dose aspirin and a statin are reasonable for patients with atherosclerotic thoracic aortic aneurysm. Antihypertensives are recommended for patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm and hypertension, whereas statin therapy is recommended for patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm and atherosclerosis. The use of low-dose aspirin is considered reasonable for patients with atherosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysm. Smoking cessation is strongly recommended for all patients with aortic aneurysms. All patients with acute aortic syndromes should receive blood pressure–lowering therapy with intravenous (IV) β-blockers as first-line agents and IV vasodilators as second-line agents.

Surgical Management

Open surgical intervention is recommended for patients with aortic root or ascending aortic aneurysms with or without aortic valve involvement and for patients with aortic arch aneurysms. If the anatomy of patients with thoracic descending aortic and abdominal aortic aneurysms is favorable, endovascular repair is preferred over open surgical repair. For patients with connective tissue disorders, hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysm, and dissection, or patients with longer life expectancy (>10 years), open surgical repair is considered reasonable.

Patients with acute type A aortic dissections should undergo emergent open surgical repair with either aortic valve suspension or replacement, depending on the degree of aortic root involvement. Patients with uncomplicated, acute type B aortic dissections should undergo medical management unless they have high-risk characteristics, in which case endovascular stenting can be considered. If the anatomy is favorable, patients with acute type B aortic dissections complicated by rupture, branch artery occlusion, malperfusion, retrograde extension of dissection flap, progressive aortic enlargement, uncontrolled hypertension, or intractable pain should undergo endovascular stenting over surgical repair. Urgent surgical repair is recommended for patients with type A or complicated type B intramural hematoma, whereas medical management is preferred for those with uncomplicated type B intramural hematoma.

Urgent surgical repair is recommended for patients with penetrating aortic ulcers, aortic rupture, or intramural hematoma of the ascending aorta. Repair is also indicated for patients with isolated penetrating aortic ulcers who have persistent pain. In cases of blunt traumatic aortic injury involving the descending or abdominal region, the choice of open or endovascular repair depends on the patient's clinical status, hospital resources, and clinician experience.

The guidelines emphasize the importance of multidisciplinary teams in managing acute aortic disease requiring urgent repair. Referral to high-volume centers, those performing 30 to 40 procedures annually, are encouraged. Studies have shown that surgical mortality rates are lower when case volume is higher.[5]

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Writing Committee Members, Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, Augoustides JG, Beck AW, Bolen MA, Braverman AC, Bray BE, Brown-Zimmerman MM, Chen EP, Collins TJ, DeAnda A Jr, Fanola CL, Girardi LN, Hicks CW, Hui DS, Schuyler Jones W, Kalahasti V, Kim KM, Milewicz DM, Oderich GS, Ogbechie L, Promes SB, Ross EG, Schermerhorn ML, Singleton Times S, Tseng EE, Wang GJ, Woo YJ, Peer Review Committee Members, Faxon DP, Upchurch GR Jr, Aday AW, Azizzadeh A, Boisen M, Hawkins B, Kramer CM, Luc JGY, MacGillivray TE, Malaisrie SC, Osteen K, Patel HJ, Patel PJ, Popescu WM, Rodriguez E, Sorber R, Tsao PS, Santos Volgman A, AHA/ACC Joint Committee Members, Beckman JA, Otto CM, O'Gara PT, Armbruster A, Birtcher KK, de las Fuentes L, Deswal A, Dixon DL, Gorenek B, Haynes N, Hernandez AF, Joglar JA, Jones WS, Mark D, Mukherjee D, Palaniappan L, Piano MR, Rab T, Spatz ES, Tamis-Holland JE, Woo YJ. 2022 ACC/AHA guideline for the diagnosis and management of aortic disease: A report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2023 Nov:166(5):e182-e331. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2023.04.023. Epub 2023 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 37389507]

Erwin Iii JP, ACC Solution Set Oversight Committee, Cibotti-Sun M, Elma M. 2022 Aortic Disease Guideline-at-a-Glance. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2022 Dec 13:80(24):2348-2352. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2022.10.001. Epub 2022 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 36334953]

Wu J, Zafar MA, Li Y, Saeyeldin A, Huang Y, Zhao R, Qiu J, Tanweer M, Abdelbaky M, Gryaznov A, Buntin J, Ziganshin BA, Mukherjee SK, Rizzo JA, Yu C, Elefteriades JA. Ascending Aortic Length and Risk of Aortic Adverse Events: The Neglected Dimension. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Oct 15:74(15):1883-1894. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.07.078. Epub 2019 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 31526537]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRokosh RS, Wu WW, Schermerhorn M, Chaikof EL. Society for Vascular Surgery implementation of clinical practice guidelines for patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm: Postoperative surveillance after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 2021 Nov:74(5):1438-1439. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2021.04.037. Epub 2021 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 34022379]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKhan H, Hussain A, Chaubey S, Sameh M, Salter I, Deshpande R, Baghai M, Wendler O. Acute aortic dissection type A: Impact of aortic specialists on short and long term outcomes. Journal of cardiac surgery. 2021 Mar:36(3):952-958. doi: 10.1111/jocs.15292. Epub 2021 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 33415734]