Introduction

Burn injuries are commonly encountered in the emergency department (ED). While burn injuries may be induced by chemical or electrical sources, friction, cold, heat, or radiation, most burn injuries are secondary to exposure to heat from hot liquids, heated solids, or fire.[1] Most burn injuries occur in children aged 1 to 16 and adults aged 20 to 59. Fire-related burn injuries account for 41% of burns, while scald injuries account for 31%.[1] Emergency medical services (EMS) should assess the extent and severity of burns through visual inspection and calculation of the affected total body surface area (TBSA) before commencing fluid resuscitation in the field.

In the United States, burns are the third most common cause of injury and mortality in children aged 5 to 9 years and the leading cause of death in children aged 1 to 14.[2] The pediatric population is especially vulnerable to burn injuries; a severe burn in a pediatric patient is defined as greater than 10% TBSA affected. This sharply contrasts severe burns in adults, defined as 20% or more of TBSA affected.[3] Burn injuries are especially dangerous due to distributive shock and the subsequent systemic inflammatory response. If inadequately treated, multiple organ failure may result.[1] Severe burn injuries primarily affect the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, respiratory, and integumentary systems.

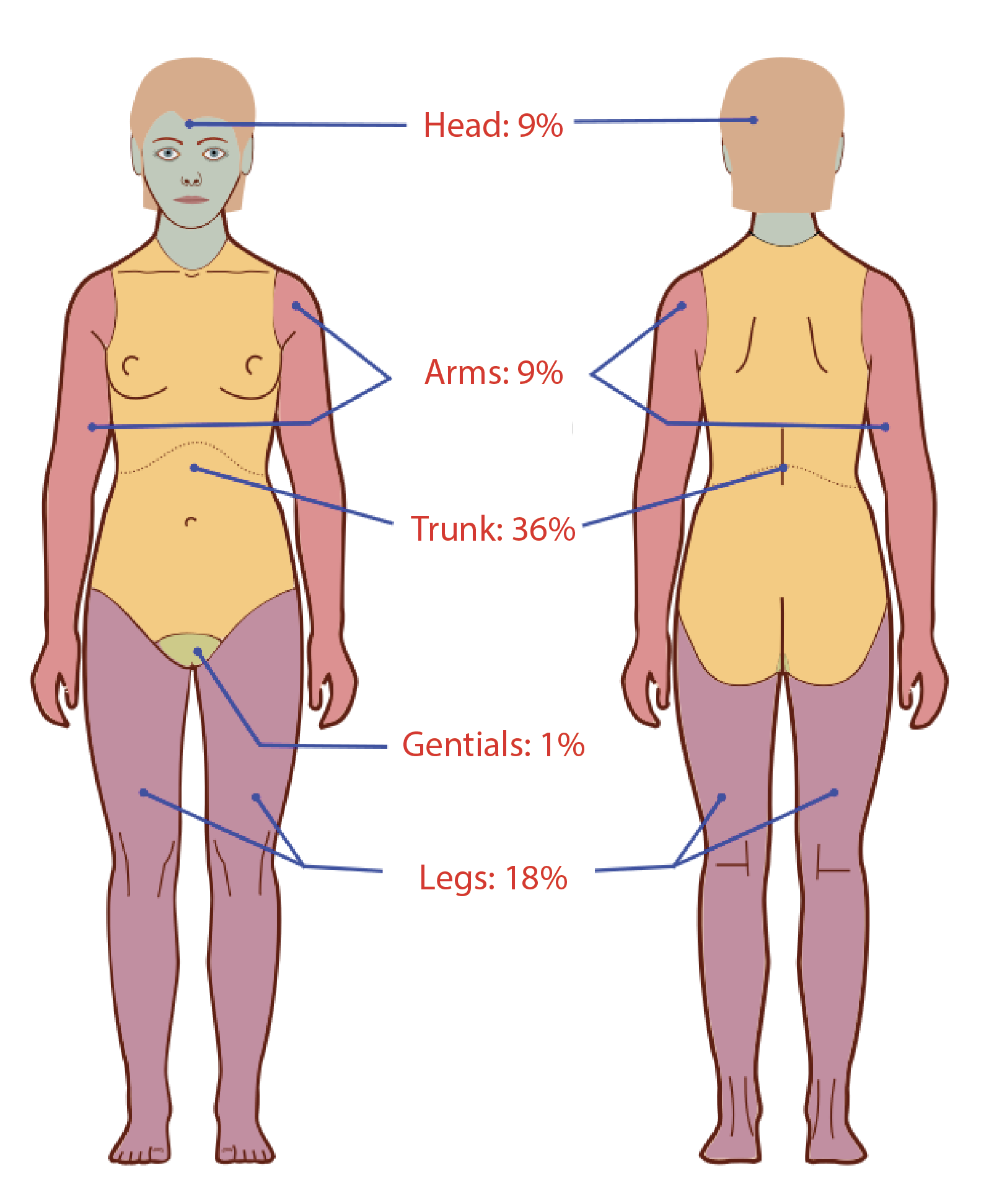

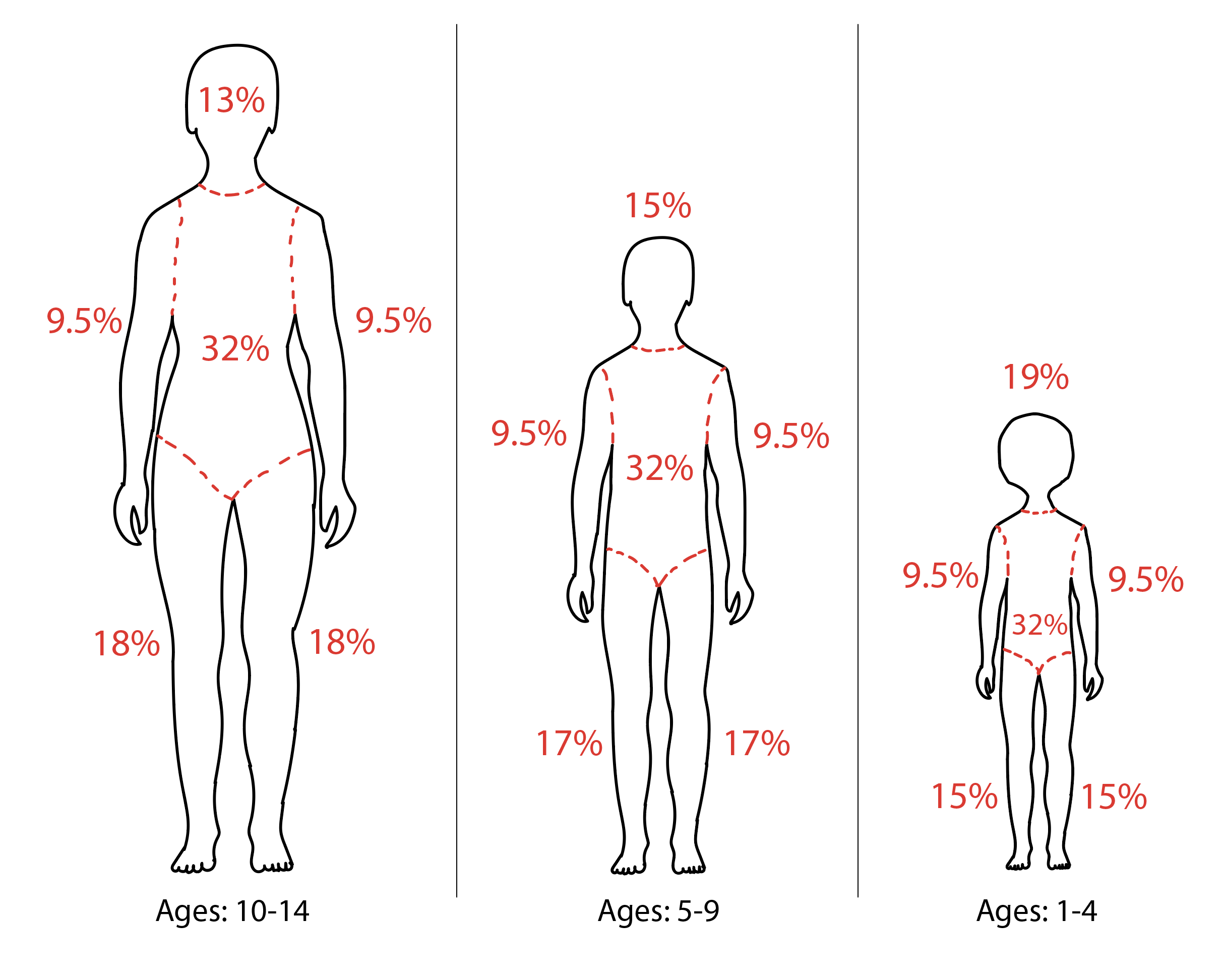

EMS traditionally employs the "Rule of Nines" tool to assess the TBSA affected by burns in patients with second- and third-degree burns. The Rule of Nines assigns each body part a percentage, usually 9%, or a multiple thereof 9 (see Image. Diagram of the Rule of 9s for Adults). These percentages can be used to quickly calculate the affected TBSA in pediatric and adult populations (see Image. Diagram of Rule of 9s Modifications for Pediatric Patients). The Parkland formula uses this estimated TBSA percentage to determine the appropriate total fluid resuscitation for patients with severe burns.

The Parkland formula multiplies the patient's total body weight by 4 and multiplies that value by the affected TBSA to calculate the total required resuscitative fluid volume. The Parkland formula recommends administering half of the required fluid volume over the first 8 hours of resuscitation and the remaining half over the subsequent 16 hours.[3] The Parkland formula is favored because it relies on visual estimates but is limited by approximating total patient body weight if that value is immediately unavailable.[4]

The "Rule of Tens" improves upon The Rule of Nines by simplifying the initial fluid resuscitation calculation. The only variable required is the affected TBSA rounded up to the nearest 10 (% TBSA x 10 = initial fluid rate in mL/h). The Rule of Tens was developed for combat prehospital providers needing a quick way to estimate resuscitation volumes for multiple burn victims in the field. The Rule of Tens aims to streamline the initial TBSA calculation and gradually reperfuse the patient, preventing any potential complications from volume overload.[5]

The Rule of Tens eliminates the need for an exact patient weight if the patient falls within the 40 to 80 kg range. By removing the need for an exact weight calculation, EMS can use the Rule of Tens to initiate initial fluid resuscitation quickly. The Rule of Tens also permits adjustments to the rate of fluid resuscitation as the patient is stabilized; this is in contrast to the Parkland formula, which requires the administration of a total volume over 24 hours.[5][6]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

The speed and accuracy of airway management and fluid resuscitation heavily influence the clinical outcome of patients with burn injuries. Using the Rule of Nines may erroneously estimate the affected TBSA, leading to inappropriate fluid resuscitation, volume overload, and pulmonary edema.[4] Studies have illustrated that visual estimation of affected TBSA is highly inaccurate compared to computer-based applications; a visual calculation of 25% to 30% affected TBSA may overestimate the actual value by as much as 20%.[4]

The Rule of Nines is prone to error when calculating the affected TBSA in pediatric patients and adults with obesity. In children, TBSA calculation requires modification with stages of physical development. For example, the adult head accounts for approximately 9% of TBSA. However, the head of a child aged 1 to 4 years is 19% of TBSA. Accurately calculating the total TBSA affected by burns is imperative to avoid over-resuscitation; the pediatric patient is especially vulnerable to the negative effects of over-resuscitation. Providers using the Rule of Nines may underestimate the required amount of fluids for patients with larger torsos or those with obesity.[4] The Rule of Tens adjusts for patients weighing over 80 kg by requiring an additional 100 mL/h of intravenous fluids for every 10 kg over 80 kg.[5][6]

However, the Rule of Tens does not correct for patients weighing less than 40 kg; this is most pediatric patients. Using the Rule of Nines with either the Parkland or Modified Brooke formula would be appropriate for initial fluid resuscitation in patients weighing less than 40 kg. Adolescent or pediatric patients estimated who weigh above 40 kg may require initial fluid resuscitation using the Rule of Tens.

Individuals of any age or weight with significant comorbidities are at increased risk of cardiopulmonary failure and require close observation in intensive care units during fluid resuscitation following a burn injury. A burn center may provide optimal treatment for such patients.

Table. Calculating Fluid Resuscitation in Patients with Burn Injuries

| Patient Weight (kg) |

Calculating Fluid Resuscitation Volumes |

| <40 | Rule of Nines with Parkland or Modified Brooke formula |

| 40 to 80 | %TBSA x 10 = initial fluid rate in mL/h (X) |

| >80 | (X) + 100 mL/h for every 10 kg above 80 kg |

Clinical Significance

The skin is a protective barrier that promotes fluid and electrolyte homeostasis. Severe burns compromise the integrity of the skin, resulting in evaporation of water, electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, and hypovolemia.[7] Burn injuries induce a hypermetabolic state, and the calculation of fluid requirements must account for increased metabolic needs in addition to evaporative losses. Under-resuscitation due to erroneous calculation of affected TBSA promotes a prolonged distributive shock state and increases mortality. Over-resuscitation predisposes to cardiopulmonary failure secondary to volume overload.[7][8]

Over-resuscitation also predisposes to the development of compartment syndrome, a medical and surgical emergency. Patients with deep or greater than 75% circumferential extremity burns are at significant risk of developing compartment syndrome. Edema within the closed osteofascial compartments of the subcutaneous and muscular layers of the extremity compromises blood flow to the affected area.[9] The initial clinical signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome are the 5 Ps: pulselessness, paresthesia, paralysis, pallor, and intense pain, particularly with passive flexion and extension of the extremity. Failure to recognize the clinical signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome may result in the need for amputation of the affected limb. Such signs, when present, warrant immediate surgical consultation and possible transfer to a burn center. Treatment for compartment syndrome involves emergent fasciotomy or escharotomy to restore normal blood flow to the affected limb.[9]

The Rule of Tens avoids under-resuscitation in adults by rounding up the affected TBSA from 9% to 10%. Utilization of the Rule of Tens also permits consideration of the response to ongoing fluid resuscitation, allowing adjustment of the fluid administration rate in response to objective markers of hydration and perfusion such as urine output, mean arterial pressure, and serum lactate levels.[10] The rate and volume of resuscitation calculated using the Rule of Tens usually fall between the rates calculated using either the Modified Brooke or Parkland formula.

Due to the compromised integrity of the skin barrier, patients with burn injuries are particularly susceptible to wound infections and sepsis, further complicating distributive shock. Burn wound infections occur within a few days to weeks of the injury. Clinical manifestations of these infections include rapid changes in wound appearance, loss of previously viable tissue, purulent exudate from the wound, or increased pain at the site of the infection. Patients may also demonstrate systemic symptoms such as fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea. The presence of 100,000 bacteria per gram of tissue from a burn wound biopsy is diagnostic of a burn wound infection; if left untreated, sepsis is likely to ensue. Commonly implicated organisms of burn wound infections include Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, Enterococcus spp, and various fungi. Treatment of burn wound infection comprises wound cleansing, debridement, and antimicrobial therapy. Topical agents such as silver sulfadiazine, silver nitrate, and mafenide acetate can be used to prevent and treat wound infections.[11][12]

It is estimated that the most significant fluid losses from severe burn injury occur during post-injury days 1 through 6.[7] Employing the Rule of Tens during the initial resuscitation period minimizes complications in the maintenance phase by avoiding fluid overload and dehydration in the initial resuscitation phase. Ensuring correct fluid resuscitation during the maintenance phase decreases the risk of complications such as dehydration, septic shock, and multiple organ failure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, Chung KK, Gibran NS, Logsetty S. Burn injury. Nature reviews. Disease primers. 2020 Feb 13:6(1):11. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0145-5. Epub 2020 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 32054846]

Arbuthnot MK, Garcia AV. Early resuscitation and management of severe pediatric burns. Seminars in pediatric surgery. 2019 Feb:28(1):73-78. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2019.01.013. Epub 2019 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 30824139]

Schaefer TJ, Nunez Lopez O. Burn Resuscitation and Management. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613546]

Moore RA, Waheed A, Burns B. Rule of Nines. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020659]

Sánchez-Sánchez M, García-de-Lorenzo A, Asensio MJ. First resuscitation of critical burn patients: progresses and problems. Medicina intensiva. 2016 Mar:40(2):118-24. doi: 10.1016/j.medin.2015.12.001. Epub 2016 Feb 9 [PubMed PMID: 26873418]

Jeng JC. Passing the Baton: The Brooke Formula, Colonel Basil A. Pruitt, and the ISR Rule of Ten. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2019 Jun 21:40(4):527. doi: 10.1093/jbcr/irz061. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30919900]

Namdar T, Stollwerck PL, Stang FH, Siemers F, Mailänder P, Lange T. Transdermal fluid loss in severely burned patients. German medical science : GMS e-journal. 2010 Oct 26:8():Doc28. doi: 10.3205/000117. Epub 2010 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 21063470]

Guilabert P, Usúa G, Martín N, Abarca L, Barret JP, Colomina MJ. Fluid resuscitation management in patients with burns: update. British journal of anaesthesia. 2016 Sep:117(3):284-96. doi: 10.1093/bja/aew266. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27543523]

Boccara D, Lavocat R, Soussi S, Legrand M, Chaouat M, Mebazaa A, Mimoun M, Blet A, Serror K. Pressure guided surgery of compartment syndrome of the limbs in burn patients. Annals of burns and fire disasters. 2017 Sep 30:30(3):193-197 [PubMed PMID: 29849522]

Jeng JC, Jaskille AD, Lunsford PM, Jordan MH. Improved markers for burn wound perfusion in the severely burned patient: the role for tissue and gastric Pco2. Journal of burn care & research : official publication of the American Burn Association. 2008 Jan-Feb:29(1):49-55. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e31815f59dc. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18182897]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiley JL, Greenhalgh DG. Infections in Burn Patients. The Surgical clinics of North America. 2023 Jun:103(3):427-437. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2023.02.005. Epub 2023 Apr 4 [PubMed PMID: 37149379]

D'Abbondanza JA, Shahrokhi S. Burn Infection and Burn Sepsis. Surgical infections. 2021 Feb:22(1):58-64. doi: 10.1089/sur.2020.102. Epub 2020 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 32364824]