Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases substantially contribute to the burden of morbidity and mortality worldwide.[1] Arrhythmias significantly contribute to cardiovascular morbidity; most cardiac arrests and sudden cardiac deaths are secondary to arrhythmias.[2] The rapid, accurate diagnosis of dysrhythmias is essential to effectively treat patients, prevent complications, and optimize patient outcomes. Electrocardiography (ECG) is a foundational diagnostic tool offering valuable insight into the function of the cardiac conduction system. However, traditional ECG recordings in clinical settings provide only a snapshot of cardiac activity, limiting their ability to capture intermittent or subtle abnormalities.[3]

Ambulatory ECG monitoring enables continuous and prolonged surveillance of a patient's cardiac rhythm in their natural environment.[4] Ambulatory ECG monitoring employs portable devices to record and analyze cardiac electrical activity over extended periods. Continuous, prolonged monitoring is more likely to detect transient or infrequent cardiac events that may go unnoticed during short-term recordings. The prototype of ambulatory ECG monitoring is the Holter monitor, invented in 1961.[5] Ambulatory ECG monitoring has continually advanced; multiple devices are now available to improve diagnostic yield.[6] Prolonged ambulatory ECG monitoring is uniquely poised to capture elusive arrhythmias, evaluate the efficacy of antiarrhythmic therapies, and assess overall cardiovascular health.[7]

This activity reviews the various ambulatory ECG monitoring devices currently in clinical use and the indications, critical findings, and clinical significance of this testing modality.

Procedures

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Procedures

Various ambulatory ECG monitoring systems are in regular clinical use. These systems include but are not limited to the Holter monitor, different event recorders, patch monitors, mobile outpatient cardiac telemetry, and various implantable devices. Additionally, several consumer devices are available for monitoring the cardiac conduction system.

Continuous ECG Monitor

Continuous ECG monitors, or Holter monitors, are the most commonly utilized ambulatory ECG monitoring devices. Holter monitors permit the continuous recording of cardiac electrical activity for an extended period, typically 24 to 72 hours. These monitors are indispensable when evaluating patients with intermittent symptoms, effectively capturing episodes of arrhythmias that might otherwise remain undetected. [8]

Holter monitors are lightweight devices comprising electrodes attached to the patient's chest and connected to a compact recording device approximately the size of a deck of cards that may be worn on the waist or carried in a convenient pouch. (See Image. Holter Monitor) Holter monitor recordings can be acquired in 2-, 3-, or 12-channel formats. The primary advantage of the Holter monitor is the capture of an extended duration of ECG data, enabling the detection and analysis of transient and infrequent arrhythmias easily missed during a snapshot ECG.

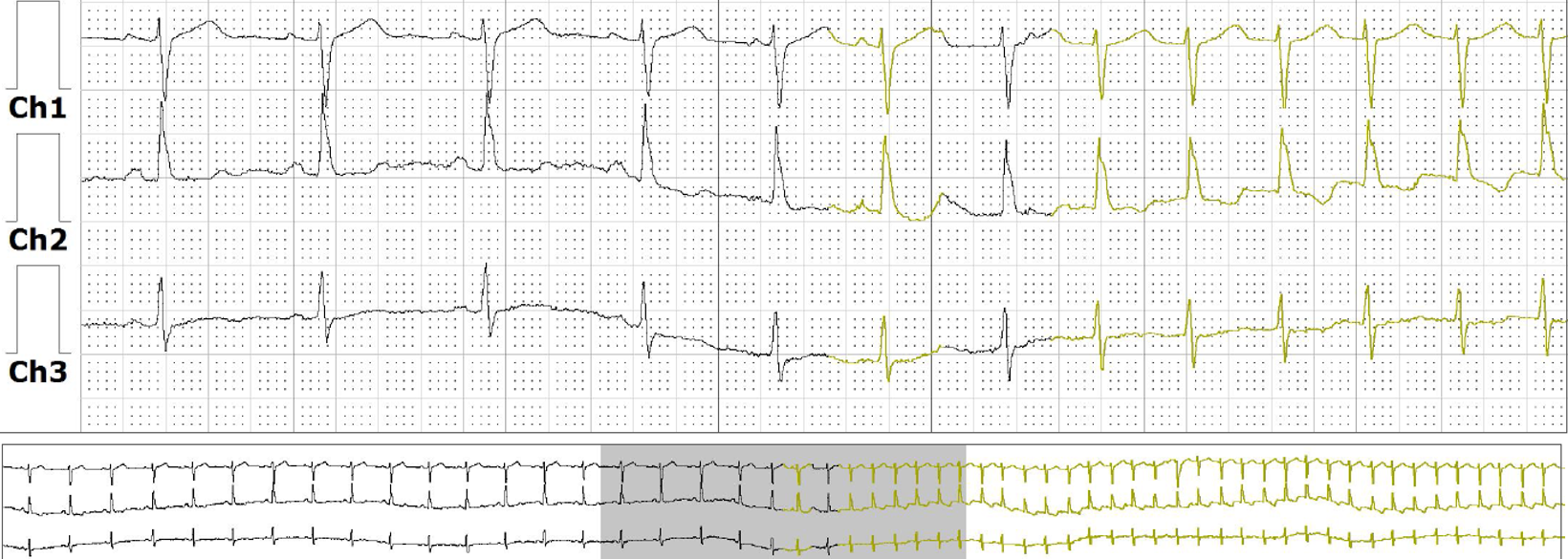

Conventional Holter monitors require active patient participation; patients must manually record their symptoms in a journal or mark their occurrence by pressing a button on the recording device. The data obtained from a Holter monitor is downloaded, and a comprehensive report is generated. Reports include various parameters, including total heartbeats, average heart rate, maximum and minimum heart rates, number and type of premature beats, the duration and type of various tachyarrhythmias, and ST segment changes. (See Image. Holter Monitor Data Output.) A Holter monitor may be the preferred modality of ambulatory ECG monitoring when evaluating patients with frequent daily symptoms.[9]

The utility of Holter monitors is limited by patient compliance and the brevity of the monitoring period. Patients must be willing to wear the monitor throughout the entire monitoring period; discomfort or skin irritation are common barriers to compliance. Due to the relatively brief duration of monitoring, a negative result does not exclude the existence of significant disease with infrequent events. Interpreting and analyzing such extensive ECG data requires expertise and is time-consuming. Holter monitors also do not provide real-time information and delay identifying essential events.[10]

Event Recorders: Loop Recorders and Post-Event Monitors

Event monitors are a suitable option for patients experiencing syncope, near syncope, or infrequent episodes of dizziness occurring weekly to monthly.[11] Traditional post-event recorders are small devices capable of recording a single ECG lead for several minutes. The patient presses a button on the device while holding it to their chest to activate the recording capability. The recorded data can be quickly downloaded, permitting real-time monitoring if the patient promptly performs the download.[12][13] Unlike a Holter monitor, a post-event recorder is unobtrusive and can be comfortably carried in a pocket when not in use; the need for chest wires is eliminated, and everyday activities are easily accomplished.

The most significant drawback of post-event recorders is the lack of continuous ECG monitoring; placing the device against the chest makes it challenging to capture brief symptomatic episodes, and asymptomatic events go unrecorded. Additionally, the onset of the episode is not recorded; this impairs accurate diagnosis.

External loop recorders address some of these limitations by continuously monitoring the cardiac conduction system, storing the data in a loop memory for 30 days, and actively recording event data when activated by the patient. External loop recorders are indicated monitoring modalities for patients with infrequent nonsyncopal symptoms; syncopal patients cannot activate the monitor when unconscious.[12] When activated, these recorders store data for a fixed period before and after the activation.

While external loop recorders and event monitors are effective for frequent symptoms, the correlation between symptoms and ECG abnormalities is low for events that occur less than once monthly. In cases where extended monitoring is necessary, implantable loop recorders may be utilized. These devices are designed to be implanted subcutaneously in the chest wall via a minimally invasive procedure performed without general anesthesia. Implantable loop recorders can record data for up to 3 years, are MRI-compatible, and have low infection and complication rates.[14][15]

Patch Monitor

Patch monitors combine user-friendly features with patient comfort. Patch monitors have an adhesive backing, adhere securely to the skin, and eliminate the need for irritating wires and electrodes. The lightweight and unobtrusive design of most patch monitors permits unrestricted daily activities. Patients can conveniently annotate symptoms using a button on the device, facilitating better correlation between symptoms and conduction events. Patch monitors are typically worn for 14 days, significantly extending the monitoring duration compared to the conventional 48-hour monitors. Prolonged monitoring increases the likelihood of identifying arrhythmias that might go unnoticed in shorter monitoring periods. A study conducted by Barret et al demonstrated that the adhesive patch monitor outperformed the Holter monitor in detecting cardiac events in patients with suspected arrhythmia.[16][17]

Mobile Cardiac Outpatient Telemetry™

In contrast to the offline analysis permitted by typical patch monitors, Mobile Cardiac Outpatient Telemetry™ (MOCT™) devices provide real-time, wireless arrhythmia monitoring, transmission, and analysis. Patients can trigger the machine to collect and automatically transmit data during symptomatic episodes.[18]

MOCT™ has demonstrated superior diagnosis of clinically significant arrhythmias compared to standard patient-triggered loop monitors.[19][20] Medic et al studied a cohort of 1000 patients with cryptogenic stroke and no history of atrial fibrillation to compare the expense and diagnostic accuracy of 30 days of MCOT™ followed by an implantable loop recorder (ILR) versus an ILR alone. The results demonstrated that an initial 30-day monitoring period with MCOT™ increased detection rates of atrial fibrillation at a cost 8 times lower than an ILR alone.[21]

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators and Permanent Pacemakers

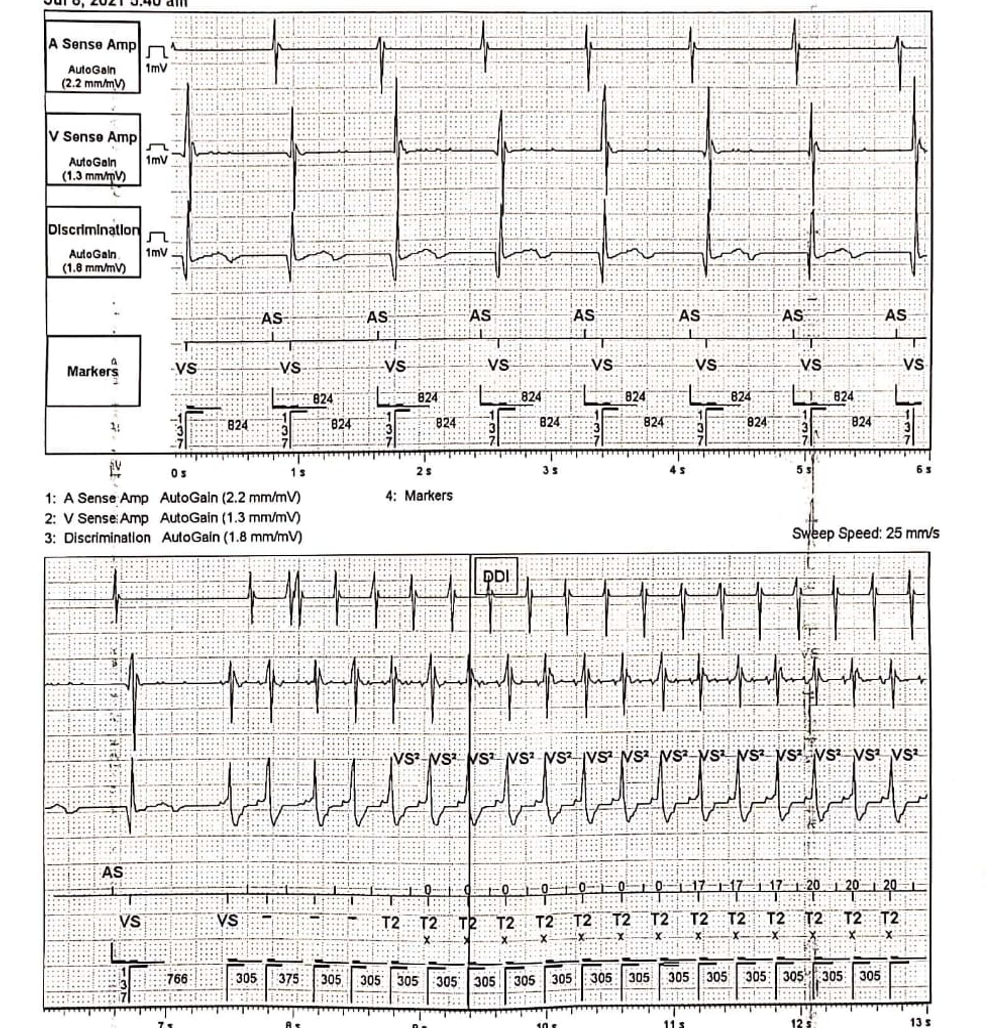

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and permanent pacemakers (PPMs) can be continuous monitoring devices with detection algorithms for arrhythmias, including supraventricular and ventricular tachycardia. (See Image. Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Recording) When appropriately programmed, these devices exhibit sensitivity and specificity of greater than 95% in detecting atrial fibrillation.[22] In specific scenarios, patients with ICDs or PPMs may undergo external ECG monitoring to assess the functionality of implanted devices and identify potential malfunctions. Device interrogation allows data retrieval regarding the frequency and duration of arrhythmias, ventricular rates, and the necessity for shock termination episodes. Additionally, remote monitoring of these devices is available to evaluate arrhythmias and the efficacy of delivered therapies.[23]

Consumer Devices

Rapidly advancing technology has led to the widespread availability of heart rate and rhythm monitors, employing smartphones as convenient storage devices for the captured data. Some of these monitors feature algorithms that can detect irregularities, particularly atrial fibrillation, offering the potential for early detection, treatment, and reduction of stroke risk. Some rhythm monitors in smartphones and handheld devices record single-lead ECG data, including rhythm strips, during symptomatic episodes; this data can be shared with physicians for review to streamline the process of atrial fibrillation detection.

The iTransmit study introduced a compact handheld monitoring device that attaches to smartphone cases. This device exhibited 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity in detecting atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation compared to traditional trans-telephonic monitors.[24] Lubitz et al conducted a study involving 455,699 participants who wore smartwatches with photoplethysmography sensors. The identification of irregular heart rhythms prompted the use of a 1-week ECG patch monitor for arrhythmia confirmation. The smartwatches achieved a 97% positive predictive value in detecting irregular heart rhythms compared to the patch monitor.[25]

Integrating heart rate and rhythm monitors with smartphones and handheld devices reshapes ambulatory cardiac monitoring. These technological innovations, along with improved algorithms and seamless data sharing, hold significant promise for the early detection and management of atrial fibrillation and other dysrhythmias, advancing personalized cardiovascular care.

Indications

Syncope

Syncope is the loss of consciousness and postural control followed by spontaneous recovery without residual neurological effects. Syncope has many etiologies, including primary cardiac causes such as bradyarrhythmias, tachyarrhythmias, or inherited disorders such as Brugada or long-QT syndromes. Correlating symptoms with rhythm is the key to confirming cardiac electrical system involvement in syncope.[26] A 12-lead ECG may establish this link; ECG monitoring over an extended period is an essential evaluation component in cases of intermittent syncope. The 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society (ACC/AHA/HRS) Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope suggest ambulatory ECG monitoring in symptomatic patients with near syncope, unexplained syncope, or episodic dizziness with an unknown cause.[27]

In a study of 85 patients with recurrent, undiagnosed syncope who underwent ILR placement to facilitate diagnosis, 42% of patients who recorded a rhythm during symptomatic syncopal episodes demonstrated an arrhythmia, usually some form of bradycardia.[28] Data indicates that external loop recorders (ELRs) may be comparably effective to ILRs. Locati et al demonstrated that ELRs offered a diagnostic yield similar to ILRs within the same timeframe in patients with syncope and presyncope.[29] Consideration of an ELR is a viable initial step for patients requiring extended ECG monitoring before resorting to implantable options.

Palpitations

The 2017 ACC/AHA/HRS Guidelines for the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Syncope also suggest ambulatory ECG monitoring in symptomatic patients with recurrent palpitations of an unknown cause. [27] Palpitations are one of the most prevalent reasons for ambulatory ECG monitoring. The underlying cause of palpitations can often be identified through an initial assessment and a 12-lead ECG; one-third of cases will have a psychiatric origin.[30] Ambulatory ECG monitoring is recommended when the cause of the palpitations remains unknown, even after obtaining a comprehensive medical history, performing a physical examination, and evaluating a resting 12-lead ECG.[31][32] Choosing an appropriate ECG monitoring device is predicated upon consideration of the clinical presentation and frequency of the palpitations. A traditional Holter monitor is indicated for patients experiencing daily symptoms. Loop recorders and patch monitors offer more diagnostic potential for those with infrequent palpitations, and opting for a 2-week monitoring period strikes a reasonable balance between diagnostic effectiveness and overall cost for most patients.[33][34]

Chest Pain and Ischemic Episodes

Ambulatory ECG monitoring is valuable for patients with atypical chest pain associated with stresses other than exercise by enabling the assessment of myocardial ischemia during routine activities. Ambulatory ECG monitoring sometimes unveils an underlying arrhythmia as the initiator of chest pain. In a study by Stern et al of 50 patients with precordial pain, where positive results in ambulatory ECG monitoring were characterized by ST-segment deviations of ≥1 mm from the baseline pattern or significant T wave inversions demonstrated that of the 32 patients with positive abnormalities, 28 had severe coronary disease during coronary angiography. Conversely, among the 18 patients without positive monitoring results, only 3 met the angiographic criteria for severe coronary disease.[35]

Standard 24-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring helps recognize and evaluate early ischemic heart disease by recording dynamic changes, even when the resting 12-lead ECG appears normal. However, dynamic ST-segment changes may be confounded by body position or cardiac medications; cautious interpretation is warranted.[36] Crawford et al. In a study of 70 patients with chest pain, normal resting ECGs, and known significant coronary artery disease, Crawford et al determined a 62% sensitivity and 61% specificity rate for ST depression during ambulatory monitoring, concluding that continuous ambulatory ECG monitoring is limited in detecting or ruling out coronary artery disease in symptomatic patients with normal resting ECGs. [37]

Ambulatory ECG monitoring likely benefits patients with chest pain suggestive of variant angina secondary to transient coronary artery spasms. The baseline 12-lead ECG is typically expected in patients with variant angina, as transient coronary vasospasm usually occurs during periods of rest and without conventional triggers such as stress or exercise; capturing ECG changes during routine activities becomes imperative to the diagnosis.[38] Clinicians can correlate patient symptoms with recorded ECG patterns, allowing for precise diagnosis, disease progression assessment, and therapeutic strategies. Significant ventricular tachyarrythmias can develop in about 50% of patients during vasospasm-induced ischemic attacks. [39] Other ECG changes commonly seen during coronary vasospasm include ST-segment elevation, premature atrial and ventricular contractions, ventricular tachycardia, and complete atrioventricular block.[40]

Normal and Critical Findings

Dilated Cardiomyopathy

Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy (NIDCM) is characterized by dilated left or bilateral ventricles and impaired systolic contractile function. NIDCM may result in life-threatening arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD). [41] The clinical utility of ambulatory ECG monitoring in NIDCM is debatable and may be of limited prognostic value. Some studies demonstrate that ambulatory ECG monitoring is a risk-stratification tool for SCD by detecting nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (NSVT) episodes.[41][42] Other studies suggest that ambulatory ventricular arrhythmias alone may not reliably predict SCD.[43] Notably, 24-hour Holter monitoring has revealed NSVT in 40% to 60% of cases of SCD occurring during ambulatory monitoring.[44]

However, the role of ambulatory ECG monitoring extends beyond prognostication by identifying atrial fibrillation, thereby influencing therapeutic decisions, including initiating anticoagulation therapy to prevent strokes in patients with NIDCM.[45] Moreover, recognizing paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias in young patients with NIDCM should warrant consideration of the possibility of underlying familial Lamin-A/C (LMNA) cardiomyopathy. [46]

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is linked to an elevated risk of sudden cardiac death (SCD), particularly among young individuals, including athletes.[47] Patients with HCM frequently report syncopal episodes and palpitations.[48] Asymptomatic NSVT with a ventricular rate exceeding ≥120 beats per minute is observed in approximately 25% of adults with HCM cases and correlates with a notable escalation in SCD risk.[49] Additionally, paroxysmal supraventricular arrhythmias manifest during ambulatory ECG monitoring in up to 38% of patients with HCM.[50]

Given the pronounced vulnerability to SCD and arrhythmias, the 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients with HCM recommends 24- to 48-hour ambulatory ECG monitoring during the initial assessment and every 1 to 2 years after that for patients with HCM.[51] This proactive approach promotes early detection and risk stratification for patients with this genetic condition, enabling clinicians to devise targeted management strategies and improve the overall prognosis and quality of life.

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias are common among individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). A study by Rusinowicz et al of 152 patients experiencing a COPD exacerbation revealed that 97% exhibited arrhythmias during 24-hour Holter monitoring. The most prevalent arrhythmia in the study was premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), occurring at an average of 1870 PVCs in 24 hours; supraventricular premature beats (SPBs) occurred at an average of 699 SPBs within the same timeframe. Additionally, supraventricular tachycardia was reported in 34% of the subjects.[52]

A retrospective investigation by Konecny et al of 6351 patients analyzed the incidence of ventricular tachycardia within a population of patients with COPD using Holter monitoring. Patients with COPD exhibited a higher prevalence of VT compared to their healthy counterparts; the occurrence of VT increased with the severity of COPD.[53] Another study demonstrated arrhythmias in 72% of patients with COPD during ambulatory Holter monitoring.[54]

Dialysis and End-Stage Renal Disease

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) have an increased risk of cardiovascular events, including arrhythmia.[55] Hemodialysis results in substantial hemodynamic and perfusion shifts; the dialysis procedure itself has been established as a contributor to the onset of atrial fibrillation.[56][57]

A cross-sectional study by Rantanen et al utilized 48-hour Holter monitors initiated just before each dialysis session in 152 patients and revealed PACs and PVCs in most patients; paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia affected 41% of studied patients. Another 8.6% of patients exhibited persistent atrial fibrillation, 3.9% experienced paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, 19.7% had NSVT, 4.6% had bradycardia, 1.3% had second-degree atrioventricular block, and 2.6% experienced third-degree atrioventricular block. PVCs were more prevalent on dialysis days, and tachyarrhythmias were more pronounced during dialysis and the immediate post-dialytic phase.[58] This data suggest that ambulatory ECG monitoring during dialysis could promote the early detection of arrhythmias in asymptomatic patients, which may prompt timely strategies for effective management.

Mitral Valve Prolapse

Arrhythmias are a frequent manifestation in patients with mitral valve prolapse. In patients with prominent symptoms or detectable auscultatory findings, ambulatory ECG monitoring demonstrates a substantial prevalence of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias. Symptoms commonly experienced by those with mitral valve prolapse include dyspnea, palpitations, syncope, and chest pain. Ambulatory ECG monitoring assesses these symptoms and establishes if arrhythmias contribute to their occurrence [59]. One study revealed that only 27% of symptomatic patients with mitral valve prolapse exhibited arrhythmias linked to their symptoms.[60]

Pre-Excitation Syndrome

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by an anomalous accessory electrical pathway within the heart and intermittent symptoms. Traditional resting 12-lead ECGs occasionally fail to detect WPW syndrome, prompting the consideration of ambulatory ECG monitoring. Among confirmed patients with WPW syndrome, ambulatory ECG monitoring has demonstrated that pre-excitation is intermittent in up to 67% of patients.[61][62]

Sinus Node Dysfunction

Historically known as "sick sinus syndrome," sinus node dysfunction is frequently associated with age-related degenerative fibrosis affecting the sinus nodal tissue and surrounding atrial myocardium. During symptomatic episodes, sinus node dysfunction commonly manifests as prolonged sinus pauses lacking an accompanying escape rhythm. Ambulatory 24-hour ECG monitoring is often required to correlate symptoms with electrocardiographic evidence. Some patients with sinus node dysfunction remain asymptomatic during sinus pauses.[63]

Sinus node dysfunction may manifest with other ECG abnormalities, including periods of severe bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, and alternating patterns of bradycardia and atrial tachyarrhythmias.[64][65] When a comprehensive history, physical examination, and initial 12-lead ECG fail to yield a diagnosis, ambulatory monitoring is a valuable tool for confirming the presence of sinus node dysfunction. A Holter monitor is recommended for individuals encountering daily symptoms, while those with less frequent symptoms are better evaluated with more prolonged monitoring.[63]

Sleep Apnea

Cardiac arrhythmias and conduction disorders are frequently encountered in patients with sleep apnea.[66] A comprehensive investigation comprising 400 patients diagnosed with sleep apnea and monitored with a 24-hour Holter device found that 48% exhibited cardiac arrhythmias during sleep.[67] Javaheri et al conducted a prospective study on 81 men with stable heart failure, 41 of whom had sleep apnea, and demonstrated that patients with sleep apnea have a high incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and atrial fibrillation.[68]

Holter monitoring may be a valuable tool for predicting the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. In a comparative analysis of 63 patients, Holter monitoring captured apnea events with 90% sensitivity and 82.6% specificity, compared to polysomnography, suggesting that Holter monitoring may enhance diagnostic and therapeutic strategies in patients with certain sleep disorders.[69]

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement

Ambulatory ECG monitoring has become essential for understanding arrhythmias before and after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). Studies using ambulatory ECG monitoring found bradyarrhythmias or tachyarrhythmias in approximately 15% of patients before TAVR, which led to treatment changes in approximately half of these cases. Identifying severe bradyarrhythmias before TAVR permits planned pacemaker implantation and decreases procedural complications. Detecting atrial fibrillation before TAVR can prompt early anticoagulation therapy and potentially reduce post-TAVR cerebrovascular events.[70]

Patient Safety and Education

To uphold patient safety during this process, healthcare providers must adhere to strict quality control measures and ensure the accurate placement and functioning of the monitoring device. Additionally, comprehensive patient education is vital to optimizing the use and management of the monitoring device. Educating patients about potential discomforts, troubleshooting procedures, and the importance of maintaining baseline activities and routines can enhance their adherence to the monitoring process and increase the overall quality of the collected data. Healthcare professionals can maximize the diagnostic yield, facilitate timely interventions, and improve patient outcomes by fostering patient safety and education in ambulatory ECG monitoring.

Clinical Significance

Ambulatory ECG monitoring plays a pivotal role in cardiology by providing continuous, prolonged ECG recording outside the clinical setting. Ambulatory ECG monitoring promotes the capture of elusive arrhythmias, gauges treatment efficacy, aids in risk stratification, and enhances syncope evaluation. As technology evolves, the potential for more advanced ambulatory monitoring devices promises further refinement of patient care strategies in cardiology.

Diagnosing Arrhythmias and Cardiac Abnormalities

Ambulatory ECG monitoring offers a dynamic insight into the heart's electrical activity throughout an extended period, enabling the detection of arrhythmias and cardiac abnormalities that might be missed during conventional ECGs. This technique captures intermittent or transient arrhythmic events, such as atrial fibrillation, bradyarrhythmias, and premature ventricular contractions. By providing a comprehensive overview of a patient's heart rhythm, ambulatory monitoring aids in accurate diagnosis and informs appropriate treatment strategies.[71]

Risk Stratification and Prognosis

Risk stratification is critical to managing cardiac patients, and ambulatory ECG monitoring contributes significantly to this process. Through continuous monitoring, clinicians can quantify the burden of arrhythmias, aiding in identifying high-risk patients who may benefit from interventions such as anticoagulation therapy or ICDs.[41]

Syncope Evaluation

Syncopal episodes often pose diagnostic challenges due to their transient nature. Ambulatory ECG monitoring offers a valuable solution by recording cardiac activity during these episodes, potentially capturing arrhythmias or cardiac anomalies that could underlie the syncopal events. This data-driven approach enhances the accuracy of diagnosis and facilitates appropriate management strategies for patients experiencing unexplained syncope.[72]

Long-Term Monitoring

Certain cardiac conditions necessitate extended monitoring to assess their impact on patient health. Ambulatory ECG monitoring conducted over an extended duration of days to months provides insight into the chronicity and variability of arrhythmic events. Conditions such as atrial fibrillation benefit from such monitoring, enabling the fine-tuning of treatment plans based on long-term trends.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Amini M, Zayeri F, Salehi M. Trend analysis of cardiovascular disease mortality, incidence, and mortality-to-incidence ratio: results from global burden of disease study 2017. BMC public health. 2021 Feb 25:21(1):401. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10429-0. Epub 2021 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 33632204]

Israel CW. Mechanisms of sudden cardiac death. Indian heart journal. 2014 Jan-Feb:66 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S10-7. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2014.01.005. Epub 2014 Feb 11 [PubMed PMID: 24568819]

Pereira H, Niederer S, Rinaldi CA. Electrocardiographic imaging for cardiac arrhythmias and resynchronization therapy. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2020 Aug 5:22(10):1447-62. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa165. Epub 2020 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 32754737]

Linker NJ, Voulgaraki D, Garutti C, Rieger G, Edvardsson N, PICTURE Study Investigators. Early versus delayed implantation of a loop recorder in patients with unexplained syncope--effects on care pathway and diagnostic yield. International journal of cardiology. 2013 Dec 10:170(2):146-51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.10.025. Epub 2013 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 24182906]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHOLTER NJ. New method for heart studies. Science (New York, N.Y.). 1961 Oct 20:134(3486):1214-20 [PubMed PMID: 13908591]

Kennedy HL. The evolution of ambulatory ECG monitoring. Progress in cardiovascular diseases. 2013 Sep-Oct:56(2):127-32. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2013.08.005. Epub 2013 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 24215744]

Ikeda T. Current Use and Future Needs of Noninvasive Ambulatory Electrocardiogram Monitoring. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan). 2021 Jan 1:60(1):9-14. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.5691-20. Epub 2020 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 32788529]

DiMarco JP, Philbrick JT. Use of ambulatory electrocardiographic (Holter) monitoring. Annals of internal medicine. 1990 Jul 1:113(1):53-68 [PubMed PMID: 2190517]

Steinberg JS, Varma N, Cygankiewicz I, Aziz P, Balsam P, Baranchuk A, Cantillon DJ, Dilaveris P, Dubner SJ, El-Sherif N, Krol J, Kurpesa M, La Rovere MT, Lobodzinski SS, Locati ET, Mittal S, Olshansky B, Piotrowicz E, Saxon L, Stone PH, Tereshchenko L, Turakhia MP, Turitto G, Wimmer NJ, Verrier RL, Zareba W, Piotrowicz R. 2017 ISHNE-HRS expert consensus statement on ambulatory ECG and external cardiac monitoring/telemetry. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2017 May:22(3):. doi: 10.1111/anec.12447. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28480632]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBolourchi M, Silver ES, Muwanga D, Mendez E, Liberman L. Comparison of Holter With Zio Patch Electrocardiography Monitoring in Children. The American journal of cardiology. 2020 Mar 1:125(5):767-771. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.11.028. Epub 2019 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 31948666]

Task Force members, Brignole M, Vardas P, Hoffman E, Huikuri H, Moya A, Ricci R, Sulke N, Wieling W, EHRA Scientific Documents Committee, Auricchio A, Lip GY, Almendral J, Kirchhof P, Aliot E, Gasparini M, Braunschweig F, Document Reviewers, Lip GY, Almendral J, Kirchhof P, Botto GL, EHRA Scientific Documents Committee. Indications for the use of diagnostic implantable and external ECG loop recorders. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2009 May:11(5):671-87. doi: 10.1093/europace/eup097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19401342]

Zimetbaum P, Goldman A. Ambulatory arrhythmia monitoring: choosing the right device. Circulation. 2010 Oct 19:122(16):1629-36. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.925610. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20956237]

Kohno R, Abe H, Benditt DG. Ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring devices for evaluating transient loss of consciousness or other related symptoms. Journal of arrhythmia. 2017 Dec:33(6):583-589. doi: 10.1016/j.joa.2017.04.012. Epub 2017 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29255505]

van der Graaf AW, Bhagirath P, Götte MJ. MRI and cardiac implantable electronic devices; current status and required safety conditions. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation. 2014 Jun:22(6):269-76. doi: 10.1007/s12471-014-0544-x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24733688]

Pachulski R, Cockrell J, Solomon H, Yang F, Rogers J. Implant evaluation of an insertable cardiac monitor outside the electrophysiology lab setting. PloS one. 2013:8(8):e71544. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071544. Epub 2013 Aug 15 [PubMed PMID: 23977071]

Turakhia MP, Hoang DD, Zimetbaum P, Miller JD, Froelicher VF, Kumar UN, Xu X, Yang F, Heidenreich PA. Diagnostic utility of a novel leadless arrhythmia monitoring device. The American journal of cardiology. 2013 Aug 15:112(4):520-4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.017. Epub 2013 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 23672988]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBarrett PM, Komatireddy R, Haaser S, Topol S, Sheard J, Encinas J, Fought AJ, Topol EJ. Comparison of 24-hour Holter monitoring with 14-day novel adhesive patch electrocardiographic monitoring. The American journal of medicine. 2014 Jan:127(1):95.e11-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.003. Epub 2013 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 24384108]

Walsh JA 3rd, Topol EJ, Steinhubl SR. Novel wireless devices for cardiac monitoring. Circulation. 2014 Aug 12:130(7):573-81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.009024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25114186]

Rothman SA, Laughlin JC, Seltzer J, Walia JS, Baman RI, Siouffi SY, Sangrigoli RM, Kowey PR. The diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias: a prospective multi-center randomized study comparing mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry versus standard loop event monitoring. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2007 Mar:18(3):241-7 [PubMed PMID: 17318994]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMiller DJ, Khan MA, Schultz LR, Simpson JR, Katramados AM, Russman AN, Mitsias PD. Outpatient cardiac telemetry detects a high rate of atrial fibrillation in cryptogenic stroke. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2013 Jan 15:324(1-2):57-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.10.001. Epub 2012 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 23102659]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMedic G, Kotsopoulos N, Connolly MP, Lavelle J, Norlock V, Wadhwa M, Mohr BA, Derkac WM. Mobile Cardiac Outpatient Telemetry Patch vs Implantable Loop Recorder in Cryptogenic Stroke Patients in the US - Cost-Minimization Model. Medical devices (Auckland, N.Z.). 2021:14():445-458. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S337142. Epub 2021 Dec 18 [PubMed PMID: 34955658]

Glotzer TV, Hellkamp AS, Zimmerman J, Sweeney MO, Yee R, Marinchak R, Cook J, Paraschos A, Love J, Radoslovich G, Lee KL, Lamas GA, MOST Investigators. Atrial high rate episodes detected by pacemaker diagnostics predict death and stroke: report of the Atrial Diagnostics Ancillary Study of the MOde Selection Trial (MOST). Circulation. 2003 Apr 1:107(12):1614-9 [PubMed PMID: 12668495]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJoseph GK, Wilkoff BL, Dresing T, Burkhardt J, Khaykin Y. Remote interrogation and monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 2004 Oct:11(2):161-6 [PubMed PMID: 15383781]

Tarakji KG, Wazni OM, Callahan T, Kanj M, Hakim AH, Wolski K, Wilkoff BL, Saliba W, Lindsay BD. Using a novel wireless system for monitoring patients after the atrial fibrillation ablation procedure: the iTransmit study. Heart rhythm. 2015 Mar:12(3):554-559. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.11.015. Epub 2014 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 25460854]

Lubitz SA, Faranesh AZ, Selvaggi C, Atlas SJ, McManus DD, Singer DE, Pagoto S, McConnell MV, Pantelopoulos A, Foulkes AS. Detection of Atrial Fibrillation in a Large Population Using Wearable Devices: The Fitbit Heart Study. Circulation. 2022 Nov 8:146(19):1415-1424. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060291. Epub 2022 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 36148649]

Morillo CA, Baranchuk A. Current Management of Syncope: Treatment Alternatives. Current treatment options in cardiovascular medicine. 2004 Oct:6(5):371-383 [PubMed PMID: 15324613]

Crawford MH, Bernstein SJ, Deedwania PC, DiMarco JP, Ferrick KJ, Garson A Jr, Green LA, Greene HL, Silka MJ, Stone PH, Tracy CM, Gibbons RJ, Alpert JS, Eagle KA, Gardner TJ, Gregoratos G, Russell RO, Ryan TJ, Smith SC Jr. ACC/AHA guidelines for ambulatory electrocardiography: executive summary and recommendations. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines (committee to revise the guidelines for ambulatory electrocardiography). Circulation. 1999 Aug 24:100(8):886-93 [PubMed PMID: 10458728]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKrahn AD, Klein GJ, Yee R, Takle-Newhouse T, Norris C. Use of an extended monitoring strategy in patients with problematic syncope. Reveal Investigators. Circulation. 1999 Jan 26:99(3):406-10 [PubMed PMID: 9918528]

Locati ET, Vecchi AM, Vargiu S, Cattafi G, Lunati M. Role of extended external loop recorders for the diagnosis of unexplained syncope, pre-syncope, and sustained palpitations. Europace : European pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac electrophysiology : journal of the working groups on cardiac pacing, arrhythmias, and cardiac cellular electrophysiology of the European Society of Cardiology. 2014 Jun:16(6):914-22. doi: 10.1093/europace/eut337. Epub 2013 Oct 24 [PubMed PMID: 24158255]

Weber BE, Kapoor WN. Evaluation and outcomes of patients with palpitations. The American journal of medicine. 1996 Feb:100(2):138-48 [PubMed PMID: 8629647]

Weitz HH, Weinstock PJ. Approach to the patient with palpitations. The Medical clinics of North America. 1995 Mar:79(2):449-56 [PubMed PMID: 7877401]

Abbott AV. Diagnostic approach to palpitations. American family physician. 2005 Feb 15:71(4):743-50 [PubMed PMID: 15742913]

Chua SK, Chen LC, Lien LM, Lo HM, Liao ZY, Chao SP, Chuang CY, Chiu CZ. Comparison of Arrhythmia Detection by 24-Hour Holter and 14-Day Continuous Electrocardiography Patch Monitoring. Acta Cardiologica Sinica. 2020 May:36(3):251-259. doi: 10.6515/ACS.202005_36(3).20190903A. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32425440]

Zimetbaum PJ, Kim KY, Josephson ME, Goldberger AL, Cohen DJ. Diagnostic yield and optimal duration of continuous-loop event monitoring for the diagnosis of palpitations. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Annals of internal medicine. 1998 Jun 1:128(11):890-5 [PubMed PMID: 9634426]

Stern S, Tzivoni D, Stern Z. Diagnostic accuracy of ambulatory ECG monitoring in ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1975 Dec:52(6):1045-9 [PubMed PMID: 1182948]

Kennedy HL, Wiens RD. Ambulatory (Holter) electrocardiography and myocardial ischemia. American heart journal. 1989 Jan:117(1):164-76 [PubMed PMID: 2643281]

Crawford MH, Mendoza CA, O'Rourke RA, White DH, Boucher CA, Gorwit J. Limitations of continuous ambulatory electrocardiogram monitoring for detecting coronary artery disease. Annals of internal medicine. 1978 Jul:89(1):1-5 [PubMed PMID: 666154]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencede Luna AB, Cygankiewicz I, Baranchuk A, Fiol M, Birnbaum Y, Nikus K, Goldwasser D, Garcia-Niebla J, Sclarovsky S, Wellens H, Breithardt G. Prinzmetal angina: ECG changes and clinical considerations: a consensus paper. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc. 2014 Sep:19(5):442-53. doi: 10.1111/anec.12194. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25262663]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrevitali M, Klersy C, Salerno JA, Chimienti M, Panciroli C, Marangoni E, Specchia G, Comolli M, Bobba P. Ventricular tachyarrhythmias in Prinzmetal's variant angina: clinical significance and relation to the degree and time course of S-T segment elevation. The American journal of cardiology. 1983 Jul:52(1):19-25 [PubMed PMID: 6858911]

Araki H, Koiwaya Y, Nakagaki O, Nakamura M. Diurnal distribution of ST-segment elevation and related arrhythmias in patients with variant angina: a study by ambulatory ECG monitoring. Circulation. 1983 May:67(5):995-1000 [PubMed PMID: 6682020]

Okutucu S, Oto A. Risk stratification in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: Current perspectives. Cardiology journal. 2010:17(3):219-29 [PubMed PMID: 20535711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHolmes J, Kubo SH, Cody RJ, Kligfield P. Arrhythmias in ischemic and nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: prediction of mortality by ambulatory electrocardiography. The American journal of cardiology. 1985 Jan 1:55(1):146-51 [PubMed PMID: 3881000]

Teerlink JR, Jalaluddin M, Anderson S, Kukin ML, Eichhorn EJ, Francis G, Packer M, Massie BM. Ambulatory ventricular arrhythmias in patients with heart failure do not specifically predict an increased risk of sudden death. PROMISE (Prospective Randomized Milrinone Survival Evaluation) Investigators. Circulation. 2000 Jan 4-11:101(1):40-6 [PubMed PMID: 10618302]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAkhtar M, Elliott PM. Risk Stratification for Sudden Cardiac Death in Non-Ischaemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Current cardiology reports. 2019 Nov 25:21(12):155. doi: 10.1007/s11886-019-1236-3. Epub 2019 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 31768884]

Finocchiaro G, Merlo M, Sheikh N, De Angelis G, Papadakis M, Olivotto I, Rapezzi C, Carr-White G, Sharma S, Mestroni L, Sinagra G. The electrocardiogram in the diagnosis and management of patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. European journal of heart failure. 2020 Jul:22(7):1097-1107. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1815. Epub 2020 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 32243666]

Taylor MR, Fain PR, Sinagra G, Robinson ML, Robertson AD, Carniel E, Di Lenarda A, Bohlmeyer TJ, Ferguson DA, Brodsky GL, Boucek MM, Lascor J, Moss AC, Li WL, Stetler GL, Muntoni F, Bristow MR, Mestroni L, Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy Registry Research Group. Natural history of dilated cardiomyopathy due to lamin A/C gene mutations. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003 Mar 5:41(5):771-80 [PubMed PMID: 12628721]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaron BJ, Ommen SR, Semsarian C, Spirito P, Olivotto I, Maron MS. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: present and future, with translation into contemporary cardiovascular medicine. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014 Jul 8:64(1):83-99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24998133]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAuthors/Task Force members, Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger MA, Borggrefe M, Cecchi F, Charron P, Hagege AA, Lafont A, Limongelli G, Mahrholdt H, McKenna WJ, Mogensen J, Nihoyannopoulos P, Nistri S, Pieper PG, Pieske B, Rapezzi C, Rutten FH, Tillmanns C, Watkins H. 2014 ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal. 2014 Oct 14:35(39):2733-79. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu284. Epub 2014 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 25173338]

Monserrat L, Elliott PM, Gimeno JR, Sharma S, Penas-Lado M, McKenna WJ. Non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: an independent marker of sudden death risk in young patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2003 Sep 3:42(5):873-9 [PubMed PMID: 12957435]

Adabag AS, Casey SA, Kuskowski MA, Zenovich AG, Maron BJ. Spectrum and prognostic significance of arrhythmias on ambulatory Holter electrocardiogram in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005 Mar 1:45(5):697-704 [PubMed PMID: 15734613]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOmmen SR, Mital S, Burke MA, Day SM, Deswal A, Elliott P, Evanovich LL, Hung J, Joglar JA, Kantor P, Kimmelstiel C, Kittleson M, Link MS, Maron MS, Martinez MW, Miyake CY, Schaff HV, Semsarian C, Sorajja P. 2020 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2020 Dec 22:142(25):e533-e557. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000938. Epub 2020 Nov 20 [PubMed PMID: 33215938]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRusinowicz T, Zielonka TM, Zycinska K. Cardiac Arrhythmias in Patients with Exacerbation of COPD. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2017:1022():53-62. doi: 10.1007/5584_2017_41. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28573445]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKonecny T, Somers KR, Park JY, John A, Orban M, Doshi R, Scanlon PD, Asirvatham SJ, Rihal CS, Brady PA. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease as a risk factor for ventricular arrhythmias independent of left ventricular function. Heart rhythm. 2018 Jun:15(6):832-838. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.09.042. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 28986334]

Kleiger RE, Senior RM. Longterm electrocardiographic monitoring of ambulatory patients with chronic airway obstruction. Chest. 1974 May:65(5):483-7 [PubMed PMID: 4274977]

Foley RN. Clinical epidemiology of cardiac disease in dialysis patients: left ventricular hypertrophy, ischemic heart disease, and cardiac failure. Seminars in dialysis. 2003 Mar-Apr:16(2):111-7 [PubMed PMID: 12641874]

Selby NM, McIntyre CW. The acute cardiac effects of dialysis. Seminars in dialysis. 2007 May-Jun:20(3):220-8 [PubMed PMID: 17555488]

Buiten MS, de Bie MK, Rotmans JI, Gabreëls BA, van Dorp W, Wolterbeek R, Trines SA, Schalij MJ, Jukema JW, Rabelink TJ, van Erven L. The dialysis procedure as a trigger for atrial fibrillation: new insights in the development of atrial fibrillation in dialysis patients. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2014 May:100(9):685-90. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305417. Epub 2014 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 24670418]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRantanen JM, Riahi S, Schmidt EB, Johansen MB, Søgaard P, Christensen JH. Arrhythmias in Patients on Maintenance Dialysis: A Cross-sectional Study. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2020 Feb:75(2):214-224. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.06.012. Epub 2019 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 31542235]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHarrison DC, Fitzgerald JW, Winkle RA. Ambulatory electrocardiography for diagnosis and treatment of cardiac arrhythmias. The New England journal of medicine. 1976 Feb 12:294(7):373-80 [PubMed PMID: 1107844]

Winkle RA, Lopes MG, Fitzgerald JW, Goodman DJ, Schroeder JS, Harrison DC. Arrhythmias in patients with mitral valve prolapse. Circulation. 1975 Jul:52(1):73-81 [PubMed PMID: 1132123]

Klein GJ, Gulamhusein SS. Intermittent preexcitation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 1983 Aug:52(3):292-6 [PubMed PMID: 6869275]

Hindman MC, Last JH, Rosen KM. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome observed by portable monitoring. Annals of internal medicine. 1973 Nov:79(5):654-63 [PubMed PMID: 4751741]

Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Barrett C, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA, Gold MR, Goldschlager NF, Hamilton RM, Joglar JA, Kim RJ, Lee R, Marine JE, McLeod CJ, Oken KR, Patton KK, Pellegrini CN, Selzman KA, Thompson A, Varosy PD. 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline on the Evaluation and Management of Patients With Bradycardia and Cardiac Conduction Delay: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2019 Aug 20:74(7):e51-e156. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.044. Epub 2018 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 30412709]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFerrer MI. The sick sinus syndrome in atrial disease. JAMA. 1968 Oct 14:206(3):645-6 [PubMed PMID: 5695590]

Kaplan BM, Langendorf R, Lev M, Pick A. Tachycardia-bradycardia syndrome (so-called "sick sinus syndrome"). Pathology, mechanisms and treatment. The American journal of cardiology. 1973 Apr:31(4):497-508 [PubMed PMID: 4692587]

Hersi AS. Obstructive sleep apnea and cardiac arrhythmias. Annals of thoracic medicine. 2010 Jan:5(1):10-7. doi: 10.4103/1817-1737.58954. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20351955]

Guilleminault C, Connolly SJ, Winkle RA. Cardiac arrhythmia and conduction disturbances during sleep in 400 patients with sleep apnea syndrome. The American journal of cardiology. 1983 Sep 1:52(5):490-4 [PubMed PMID: 6193700]

Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, Corbett WS, Nishiyama H, Wexler L, Roselle GA. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998 Jun 2:97(21):2154-9 [PubMed PMID: 9626176]

Lao M, Ou Q, Li C, Wang Q, Yuan P, Cheng Y. The predictive value of Holter monitoring in the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of thoracic disease. 2021 Mar:13(3):1872-1881. doi: 10.21037/jtd-20-3078. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33841975]

Muntané-Carol G, Philippon F, Nault I, Faroux L, Alperi A, Mittal S, Rodés-Cabau J. Ambulatory Electrocardiogram Monitoring in Patients Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2021 Mar 16:77(10):1344-1356. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.12.062. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33706878]

Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, Barsness GW, Blum K, Cvach M, Lampert R, May JL, McDaniel GM, Perez MV, Sendelbach S, Sommargren CE, Wang PJ, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update to Practice Standards for Electrocardiographic Monitoring in Hospital Settings: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017 Nov 7:136(19):e273-e344. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527. Epub 2017 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 28974521]

2018 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of syncope., Brignole M,Moya A,de Lange FJ,Deharo JC,Elliott PM,Fanciulli A,Fedorowski A,Furlan R,Kenny RA,Martín A,Probst V,Reed MJ,Rice CP,Sutton R,Ungar A,van Dijk JG,, European heart journal, 2018 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 29562304]