Introduction

The most common upper extremity fractures presenting to the emergency department are distal ulna and radius injuries.[1] First responders, physicians, and support staff must understand how to manage these injuries.[2] The appropriate treatment for a distal ulna fracture is typically surgical correction of the radius first. Once the radius is stable, most distal ulna fractures heal well with conservative management alone. However, healthcare professionals must consider patient factors such as age, activity level, and expectations to maximize outcomes.

While most distal ulna injuries do not undergo surgery, there are situations where intervention is indicated.[3] Poor understanding of this condition can lead to malunion, weakened grasp, and other serious complications.[4][5] This review provides healthcare professionals from multiple disciplines with a better understanding of distal ulna fracture management.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Both distal ulna and radius fractures are usually the results of a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH). The predominant wrist position is dorsiflexion. In older individuals, the fracture pattern is usually extraarticular from low-energy causes. The opposite is true of younger patients who suffer intraarticular injuries from high-impact trauma. High energy mechanisms also increase the likelihood of a simultaneous distal ulna fracture.[6][7]

The ulna styloid is the most fractured part of the ulna and is found in 80% of intraarticular distal radius injuries.[4][5] Distal ulnar metaphyseal fractures occur within 5 cm of the dome of the ulnar head; only 5% of distal radius fractures present with this associated injury. The least common presentation is an ulnar head fracture, which is a cause of wrist instability.[8][6]

Isolated fractures of the distal ulna occur without an accompanying radius injury. A nightstick fracture (isolated ulnar shaft fracture) is usually the result of a direct blow to the ulna while a person is attempting to shield themselves with their arms.[6][7][9][10] Other less common mechanisms involve extreme supination or pronation. Healthcare providers should always maintain a high index of suspicion for possible abuse with any upper extremity fracture presenting with an unclear mechanism of injury, as they have been tied to intimate partner violence.[11] However, two recent retrospective studies failed to demonstrate any specific correlation between distal ulnar shaft fractures and abuse in children.[12][10]

Isolated ulnar physeal injuries are uncommon and have a greater propensity for early growth plate arrest.[13] Proper treatment must be provided as the ulnar epiphyseal plate is responsible for up to 80% of ulna growth. Isolated ulna fractures of the styloid and metaphysis are rare.[5][4] Support structures of the wrist, the triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC), and the distal radioulnar joint (DRUJ) are also commonly injured.[6]

Epidemiology

Over 40% of distal radius fractures have a concomitant injury to the distal ulna.[5][14] Approximately 1 in 6 fractures treated in the acute care setting involve the distal radius, which comprises 1.5% of all emergency department visits.[15] The bimodal distribution of patients affected is generally young men and older women.[16]

Osteoporosis is a significant risk factor, placing advanced-age individuals and postmenopausal women at risk. Obesity, a history of falls, alcohol abuse, and dementia are other important risk factors.[17]

Healthcare providers should anticipate an increased incidence of these injuries as the average life expectancy rises in the United States. In children, distal ulna physeal fractures account for 5% of physeal fractures, and Salter-Harris type II (metaphysis and physis involvement) is the most common fracture type in this age group.[18]

Pathophysiology

Anatomy

Ulna

The ulna is the medial forearm bone, and it narrows distally. The major landmarks of the distal ulna are the metaphysis, styloid, and head. Biomechanically, the distal ulna acts as a stationary object for the radius to move around. This arrangement causes various load changes on the wrist depending on the grip and degree of pronation-supination. The ulnocarpal joint carries approximately 20% of the load capacity when in a neutral position.

Ulnar Styloid

The ulnar styloid is a bony protrusion on the distal aspect of the ulnar head and is the attachment site for the superficial dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments. These ligaments are the primary stabilizers of the DRUJ. The ulnar styloid is also an attachment site for the TFCC, providing support and protection for the ulnar side of the wrist.[6]

Distal Radioulnar Joint (DRUJ)

Assessment of DRUJ stability is essential in determining if a distal ulna fracture requires surgical correction. The DRUJ maintains equilibrium during rapid energy load transfers between the forearm and the wrist during forearm pronation-supination. Thus, the DRUJ is crucial in facilitating the efficient lifting of objects.[19]

Ulnar Head

The dome and the seat comprise the ulnar head, known as the "keystone" for the DRUJ. The dome abuts the carpus, and the cartilage-covered seat articulates with the sigmoid notch to form the DRUJ.

Fovea

The fovea acts as the central axis of rotation for the ulnar head. In contrast to the styloid, it provides the attachment site for the deep dorsal and palmar radioulnar ligaments (aka the ligamentum subcruentum) that support the DRUJ. It also attaches to the TFCC, an intricate support system that preserves ulnar-sided wrist stability.

Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC)

The TFCC prevents excessive DRUJ translation via the deep dorsal and volar radioulnar ligaments. Due to the complex interactions between the distal ulna, radius, carpus, and TFCC, consensus on the pathophysiology and treatment of the distal ulna has not been achieved.[8]

Pathology

Ulnar Styloid Fractures

The importance of the ulnar styloid on wrist stability has long been debated.[20] Since the radioulnar ligaments attach to the styloid base, operative intervention is generally considered if greater than 2 mm of displacement is present. Over 40% of ulnar styloid fractures occur at the base level.[21] Theoretically, this should compromise TFCC and DRUJ functions. However, recent studies have challenged this notion by demonstrating no compromise in long-term outcomes with nonoperative management of ulnar styloid fractures.[20] The ulnar styloid fractures are managed based on their long-term effect on the stability of the DRUJ. The ligaments that stabilize the ulnar styloid determine whether a particular fracture would cause DRUJ instability.[5]

Non-Styloid Distal Ulnar Fractures

Injuries not limited to or not involving the ulnar styloid are less common but have worse outcomes. Isolated distal ulna fractures (injuries without a concomitant distal radius fracture) and ulnar head fractures correlate with wrist instability as they cause interosseous membrane, DRUJ, and TFCC injuries.[8] Ulnar head fractures impair forearm rotation and require intervention.

History and Physical

History

The history and physical evaluation are similar to a distal radius fracture workup. Examples of pertinent history include age, hand dominance, the onset of injury, location, mechanism, previous surgeries, osteoporosis, drug or alcohol use, motor or sensory deficits, decreased range of motion, and comorbidities. A detailed mechanism of injury is essential and should focus on noting the force of impact, extremity position upon contact, and acute changes in the range of motion, strength, and sensation afterward.[8]

Physical Exam

A comprehensive physical exam to rule out potential missed injuries should come first to determine a need for further evaluation. The bilateral upper extremities are compared to obtain baseline strength, sensation, and range of motion. The assessment then focuses on the injury itself. Any compartment swelling, ecchymoses, abrasions, open wounds, and deformities that may indicate a need for urgent or emergent intervention are noted. Distinguishing specific anatomical areas of point tenderness requires specificity (ie, ulnar styloid, fovea, Lister's tubercle).

Starting with a more generalized approach, it also recognizes confounding information. Discovering an ipsilateral weakness in a patient with a previous stroke or cold fingers from Raynaud disease is one example. Grip strength, wrist flexion, extension, and pronosupination are evaluated and compared to the uninjured extremity.

A thorough neurovascular examination is needed as any acute deficits may warrant urgent surgical exploration by a hand surgeon. Key provocative maneuvers of the distal forearm include the "OK" sign (anterior interosseous nerve palsy), "thumbs up" sign (posterior interosseous nerve palsy, "crossing the fingers" maneuver (ulnar motor nerve palsy), and "wrist drop" (radial nerve palsy).[22][23] The capillary refill, Allen's test, and a Doppler ultrasound are utilized to evaluate the vascular injury.[24]

Distal Ulna-Specific Assessments

Careful inspection of the ulnar aspect of the wrist to localize tenderness is critical as the differential for ulnar-sided wrist pain is extensive in the absence of obvious injury.[25] The fovea sign can test for ulnar-sided pathology. The two most common conditions associated with a positive fovea sign are foveal disruption and lunotriquetral ligament injury, but they can also indicate DRUJ instability.[26]

Assess the DRUJ intraoperatively before and after repairing the concomitant distal radius fracture. This step determines if the distal radius repair improved DRUJ stability or if the distal ulna may require surgical intervention. Recent literature has questioned whether an assessment of the DRUJ is a reliable indicator for operative intervention on distal ulna fractures since what defines "unstable" is subject to interpretation. However, it remains a standard part of the intraoperative assessment.[5]

An "unstable" DRUJ assessment has been described as the abnormal translation of the radius about the distal ulna in the forearm's neutral, pronated, and supinated positions. The ulnocarpal stress test is another provocative maneuver that can assess for possible TFCC injury, ulnar styloid fractures, ulnocarpal abutment syndrome, ECU injury, or DRUJ subluxation.[25][27]

Fovea Sign

- Position the forearm in neutral rotation.

- Palpate the ulnar styloid process.

- Find the flexor carpi ulnaris tendon (FCU).

- The fovea is located between the ulnar styloid and FCU.

- It is just proximal to the level of the pisiform and just distal to the ulnar head.

- A positive test result is tenderness with direct palpation on the ulnar fovea.

DRUJ Assessment

- Flex the patient's elbow 90° and position the forearm neutrally.

- Take the distal radius with one hand and the distal ulna with the other.

- Move the distal ulna dorsally and volarly while keeping the distal radius fixed.

- Repeat the above steps with the forearm in pronation and supination.

- The DRUJ is considered unstable if increased laxity is appreciated with translation, clunking, or lack of an endpoint is reached.[20]

Ulnocarpal Stress Test

Evaluation

Labs

Laboratory workup includes a CBC, BMP, and CRP to assist with preoperative planning or rule out infection but does not assist in diagnosing a distal ulna fracture.

Radiograph

The gold standard for diagnosing distal forearm fractures is plain film.[28] Initial diagnostic imaging consists of AP, lateral, and oblique views of the elbow, forearm, and wrist. Radiographs of the elbow assist in ruling out occult injury.[8] Since a critical determinant of distal ulna stability is the appropriate treatment of the distal radius, assessing radial inclination, volar tilt, and radial height on a radiograph is essential to decide if surgery is necessary—test DRUJ stability using a lateral view, although CT is more accurate. More than 5 mm radioulnar distance in the injured wrist compared to the uninjured on plain film may indicate DRUJ subluxation.[20]

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT is used for preoperative planning, suspected occult fractures, comminution, and intraarticular fractures. Unique applications of CT for distal ulna fractures include DRUJ instability, TFCC or intraosseous membrane injury, ulnar head fractures, and isolated intraarticular ulna fractures.[20][29]

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

MRI is the most accurate noninvasive modality for assessing if a TFCC or DRUJ injury is present (arthroscopy is the gold standard for TFCC and DRUJ injuries).[30] It can distinguish whether a TFCC tear is central or peripheral. Like CT, it is also used for preoperative planning. Some studies have demonstrated that Magnetic Resonance Arthrography (MRA) may be more precise than MRI in determining the extent of TFCC tears but is still not commonly utilized.[31]

Ultrasound

Useful for fracture identification in the emergency department setting. Without radiation risk, it is becoming popular for rapid fracture identification and an alternative for patients susceptible to radiation exposure, such as children and pregnant women. It also has shown promise in identifying ligamentous injuries. A meta-analysis of 16 studies, including over 1,200 patients, exhibited high sensitivity and specificity for diagnosing distal forearm fractures. The main disadvantage is that it is more operator-dependent than other modalities.[28]

Treatment / Management

Nonoperative Management

More distal ulna fractures are treated nonoperatively. The distal radius fracture should be stabilized first, then the distal ulna fracture should be assessed. A high threshold for operating on ulnar styloid fractures should be maintained unless the displacement is greater than 2 mm at its base. If the DRUJ is stable, treat with a long-arm cast for 2 to 4 weeks. If the DRUJ is unstable, closed reduction and immobilization with a long-arm cast for the first 6 weeks to limit pronation-supination.[4][5]

After re-evaluation, a short arm cast is placed for 4 to 6 weeks if the fracture is healing appropriately. An unstable DRUJ may ultimately require surgical intervention. Mackay et al found no difference in outcomes with short-arm versus long-arm casting or arm positioning for isolated ulnar shaft fractures.[9] The most important determinant of a successful outcome was early mobilization. Hussain et al demonstrated no difference in functional outcomes between conservative and operative management of isolated ulnar shaft fractures in patients placed in long-arm casting.[32]

Operative Management

There is no standard treatment algorithm for distal ulna fractures.[32] Nonreducible and unstable distal ulna fractures still benefit from surgical care.[5] Generally, the distal radius's degree of stability and fracture pattern determines the outcome. If indicated, the distal radius deformity is corrected surgically, and then the distal ulna fracture is evaluated intraoperatively. If unstable, repair the distal ulna fracture at that time.[5]

Fractures of the base of the ulnar styloid with an initial displacement of more than 2 mm need open reduction and internal fixation.[8] Specifically, if the ulnar styloid is displaced in a radial direction, suggesting a detachment of the ulno-radial ligament, the need for surgery is more justified. For the ulnar head fractures, fracture pattern, displacement, and stability must be assessed before deciding on operative management.[33] Three operative techniques for distal ulnar fractures and subtype considerations are summarized below.

Kirschner Wire (K-wire)

Kirschner wires should be considered for the ulnar styloid base and distal metaphyseal fractures, as well as DRUJ injuries. They are quick and minimally invasive but relatively weak constructs that require removal after 4 to 6 weeks. Tension bands, suture fixation, and interosseous wiring are options for osteoporotic or complicated fracture patterns.[3]

Plate Screw Fixation

Lag screws should be used for large oblique fracture fragments.[8] Plates can reduce complicated fractures, but achieving adequate purchase can be challenging.[3] Consider mini-condylar locking and blade plates for more complex head and neck fractures. Volar placement of the plate reduces postoperative pain complaints thanks to a more substantial soft tissue buffer. Locking compression plates is versatile and acceptable for patient satisfaction scores and functional outcomes. The distal hook is the defining feature of these plates, which orientates the surgeon for more accurate placement and improved reductions with decreased operating time.

Salvage Procedures

Salvage procedures should be utilized when comminution and stability prohibit alternatives.[8] The most commonly used is the Darrach procedure, which excises the ulnar head and addresses severe TFCC and DRUJ injuries. Other options are the Suave-Kapandiji and ulnar head arthroplasty. The Aptis-Scheker DRUJ prosthesis developed by Dr. Luis Scheker and the Christine M. Kleinert Institute in Louisville, Kentucky, has demonstrated significant functional improvement in high- and low-demand individuals with DRUJ injuries compared to ulnar head prostheses alone. The advantage is that the DRUJ replacement is not affected by pathology at the sigmoid notch, making previous ulnar head prostheses often unreliable in the long term.[34]

Ulnar Styloid Fractures

Nonoperative versus operative management is controversial. Conventional thought is that greater than 2 mm of displacement of the styloid base warrants surgical correction, but evidence suggests this is not always necessary.[5][20][35] Options include suture fixation, K-wires, and volar plating.[8][5][36](B3)

Distal Ulnar Metaphyseal Fractures

Undertreating these fractures can lead to interosseous membrane injury and decreased forearm function. The indications to operate are (1) persistent instability after the intervention, (2) the presence of severe comminution, (3) greater than 50° of displacement, or (4) more than 10° of angulation.[4][37][3] Treatment with K-wires, tension banding, intraosseous wiring, or mini-locking plates is normally indicated. Mini-locking plates minimize postoperative pain by utilizing fewer screws for fixation than other designs.

Distal Ulnar Neck or Shaft Fractures

Surgical intervention for isolated ulnar shaft fractures is controversial. The two most common indications are irreducibility and greater than 5 mm (50% or more) of displacement.[9] Surgical intervention has been shown to improve functional outcomes and accelerate healing. Blade plating or tension bands with internal locking screws are commonly used.[5] However, a 2012 Cochrane Database Review found no clear advantage of which operative technique consistently led to better outcomes.[38] (A1)

Isolated Ulnar Head Fractures

Unlike other locations on the distal ulna, most of these fractures require surgery. The literature available on operative management is limited. Nonoperative management is reserved only for nondisplaced ulnar head fractures with minimal comminution. Instability is defined as (1) significant displacement, (2) comminution, or (3) mild displacement but with intra-articular extension. Headless screws are indicated for inter-articular extension, tension bands for ulnar styloid involvement, and condylar blade or internal locking plates for an extraarticular extension.[5]

TFCC Injury

TFCC tears typically heal without operative intervention. However, consider operative intervention for a persistently unstable DRUJ despite distal radius and ulna fixation.[8][20] Stabilizing the TFCC with K-wire placement will facilitate improved DRUJ stability. The wafer procedure is used for more extensive injuries. Arthroscopic diagnosis, debridement, and repair are the gold standard for these injuries.[31]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes the following:

- Fractures of both forearm bones

- Distal radius fracture

- Distal radioulnar joint arthritis (DRUJ OA)

- Distal ulnar nonunion/malunion

- DRUJ injury

- DRUJ subluxation

- Elbow fracture

- Elbow dislocation

- Extensor carpi ulnaris injury

- Extensor carpi ulnaris tendonitis

- Galeazzi fracture (distal third radial shaft fracture and concomitant DRUJ injury)

- Hook of hamate fracture

- Isolated ulnar shaft fracture (“nightstick” or “Parry” fracture)

- Pisotriquetral arthritis (PTA)

- Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) injury

- Triquetral fracture[25]

- Triquetral nonunion

- Ulnocarpal abutment syndrome (UCAS)[25][27]

- Ulnocarpal arthritis

- Ulnar tunnel syndrome

- Ulnar variance

Staging

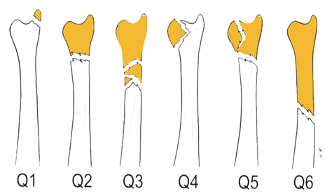

Distal ulna fracture classifications depend on fracture pattern, location, intraarticular involvement, and distal radius stability. The AO Comprehensive Classification is the most cited as it is associated with distal radius fracture injury.

AO Comprehensive Classification

- Q1 - Ulnar styloid base fracture

- Q2 - Simple ulnar neck fracture

- Q3 - Comminuted ulnar neck fracture

- Q4 - Ulnar head fracture

- Q5 - Combined ulnar neck and head fracture [4]

Distal Ulnar Metaphyseal Fractures

- Type A - Simple ulnar neck fracture

- Type B - Fracture of the ulnar neck and styloid

- Type C - Fracture of the ulnar head

- Type D - Comminuted ulnar head and neck fracture [37]

Ulnar Neck Fractures Classification

- Type I - Simple ulnar neck fracture

- Type II - Inverted T or Y-shaped fracture

- Type III - Combined ulnar neck and ulnar styloid fracture

- Type IV - Comminuted ulnar neck fracture [4]

Ulnar Head Fractures Classification

- Two Types

- Ulnar head fractures alone

- Ulnar head fracture with extraarticular distal ulna extension (i.e., including the ulnar styloid) [37]

Nightstick Fracture Criteria

Four criteria are necessary.

- No radius fracture

- Transverse fracture pattern

- Distal third of the forearm

- Minimal displacement [10]

Prognosis

In general, distal ulna fractures have good prognoses when appropriately managed. Many contributing factors play a role, and the best outcomes are achieved when treatment is individualized to meet patient needs. Xiao et al reported the best postoperative range of motion results with simple cast immobilization. Grip strength had the best prognosis when K-wire stabilization of the distal ulna fracture was performed. However, there were no differences in patient satisfaction or long-term function.

Ulnar Styloid Fractures

Ulnar styloid fractures generally have good outcomes without surgical intervention. Kim et al demonstrated successful nonoperative management of ulnar styloid base fractures, including those with displacement more significant than 2 mm.[20] Ayalon et al found no significant difference in healing rates between intraarticular and extraarticular ulnar styloid fractures.[39]

Non-styloid Distal Ulnar Fractures

Non-styloid distal ulnar fractures more often require operative intervention to obtain satisfactory outcomes compared to styloid fractures.[37] Comminuted intraarticular distal ulna fractures are associated with a poor prognosis and DRUJ injury. Distal ulnar head fractures have the worst prognosis and usually require surgical intervention. Non-styloid injuries are more likely to cause chronic grip weakness, decreased range of motion, and pain.[5]

Complications

Distal Forearm Injuries

There are many potential complications resulting from distal forearm fractures, including compartment syndrome, neurovascular injury, tendon rupture, arthritis, carpal tunnel syndrome, and malunion/nonunion. Inappropriate management of a distal ulnar fracture can result in decreased pronation-supination, chronic ulnar-sided wrist pain, DRUJ instability, tendon injury, and arthritis.[4] Hardware removal is commonplace due to patient complaints. This is primarily due to the decreased soft tissue coverage at the distal ulna than the distal radius.

Distal Ulnar Metaphyseal Fractures

The ulnar nerve and artery are located just dorsal to the flexor carpi ulnaris and are at risk for injury during dissection and plate fixation. The ulnar nerve bifurcates into the dorsal sensory branch approximately 9 cm proximal to the distal wrist crease. It arises from the deep fascia 1 to 4 cm proximal to the ulnar styloid.[4]

DRUJ Injury

Injury to the distal radioulnar joint can risk damage to the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) and extensor digiti minimi (EDM). DRUJ injury can result in ligament entrapment, limiting wrist mobility and reducing grip strength.[4]

Malunion

Distal ulna fracture malunion is uncommon and unlikely to occur if appropriate reduction and fixation are performed. Treating the distal radius alone makes malunion unlikely in concomitant distal radius fractures.[8] Treat symptomatic patients with bone grafts, which can be vascularized or non-vascularized. Potential harvest sites include the iliac crest (small segments <6 cm), fibula (large segments >6 cm), or femoral condyle.[8]

Nonunion

Ulnar styloid nonunion is frequently encountered, with an incidence between 20% to 70%.[5][4][8] However, most cases are asymptomatic and managed conservatively—symptomatic patients present with ulnar-sided wrist pain, especially with rotation. Focal tenderness over the ulnar styloid is usually present. Consider surgery if symptoms do not improve or the nonunion may jeopardize wrist stability. For example, Nonunion at the styloid base puts the primary wrist stabilizers (superficial radioulnar ligaments) at risk for injury.[5]

Rarely, nonunion can lead to other complications such as carpus abutment, ECU tendon impingement, TFCC detachment, or DRUJ instability.[8] Nonunion treatment options include excision with or without reattachment of bony nonunion and ligaments, arthroscopic intervention, bone graft, or osteotomy. Isolated ulnar shaft fractures have worse nonunion rates compared to other distal ulnar fractures, especially if displacement is more than 5 mm.[9]

Specific Operative Complications

- Darrach Procedure is associated with radioulnar pain and impingement[8]

- Tension Banding can cause nerve and soft tissue irritation secondary to pin placement or migration.[40]

- Plate Fixation frequently leads to symptomatic hardware prominence, irritation of the dorsal branch of the ulnar nerve, longer operative times, ECU and FCU tendinopathy, and tendon rupture.

- Scheker DRUJ Prosthesis can cause extensor carpi ulnaris tendinitis but is managed by placing an adipofascial flap between the prosthesis and tendon.[34]

Consultations

Distal ulna fractures may warrant surgical consultation. At the discretion of the emergency physician, simple and nondisplaced distal ulna fractures can be immobilized and provided outpatient follow-up with an orthopedic or hand surgeon. However, urgent evaluation is recommended for complex or irreducible fractures or concerns for neurovascular compromise.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Parents, caretakers, and healthcare professionals must recognize that upper extremity injuries can be a sign of nonaccidental trauma in at-risk populations. Perform a comprehensive history and physical evaluation to rule out occult injuries. Lastly, educate patients and family members on possible non-operative and operative distal ulna fracture complications. Significant complications include compartment syndrome, neurovascular injury, occult fractures, and hardware irritation. Patients should notify a medical professional immediately for any acute weakness, paresthesias, cold extremities, or skin color changes.

Pearls and Other Issues

Key facts regarding distal ulnar fractures are as follows:

- The most common mechanism of injury for both distal radius and ulna fractures is from a fall on an outstretched hand (FOOSH).

- The most common distal ulna injury presentation is a distal radius fracture with a neighboring ulnar styloid fracture.

- An ulnar styloid fracture with greater than 2 mm at its base is at increased risk of DRUJ instability and may require surgical intervention.

- An isolated distal ulnar shaft fracture is rare and should warrant evaluation for possible abuse in at-risk populations (ie, nightstick fracture).

- In cases where both distal radius and ulna fractures are present, the DRUJ should be assessed before and after fixation of the distal radius to determine if the distal ulna requires repair.

- Most distal ulna fractures only need proper stabilization of the concomitant distal radius fracture to heal appropriately.

- Hardware irritation is a common complaint with distal ulna fracture repair due to inadequate soft tissue coverage.

- Extensor carpi ulnaris rupture and ulnar neurovascular structures are at risk with distal ulna injuries and operative repair.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

First responders improve patient care when an appropriate history and physical evaluation are performed in the field, especially in high-energy trauma like motor vehicle accidents. Noting the vehicle size, speed, location (ie, highway, side of a vehicle damaged), airbag deployment, seatbelt use, extrication time, etc, can be invaluable to emergency and trauma physicians when deciding on a treatment plan. Whenever possible, distal forearm injuries should be immobilized at the scene to minimize discomfort, displacement, and damage to critical surrounding structures. Splint materials should be available at the scene, but even temporary materials like cardboard can provide enough stabilization for safe transport.[41]

Once in an acute care facility, triage should determine whether the patient warrants a possible trauma activation or is safe to be seen nonemergently. Initiate Advanced Trauma Life Support if there is a concern for life-threatening injuries. Nurses, physicians, and other support staff should take histories and perform secondary and tertiary surveys to rule out occult injuries. Open fractures require urgent surgical evaluation, exploration with washout, antibiotics, and tetanus prophylaxis. Urgent consultation with orthopedic or hand surgery services should be done, especially in severe instability or soft tissue compromise.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Volar Ulnar Plate. Developed by Dr. William Geissler to repair a distal ulna fracture. Placed just proximal to the sigmoid notch to minimize restriction of motion.

Used with permission from Dr. William Geissler (Management Distal Radius and Distal Ulnar Fractures with Fragment Specific Plate. J Wrist Surg 2013;2:190-194)

References

Karl JW, Olson PR, Rosenwasser MP. The Epidemiology of Upper Extremity Fractures in the United States, 2009. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2015 Aug:29(8):e242-4. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000312. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25714441]

Geissler WB. Management distal radius and distal ulnar fractures with fragment specific plate. Journal of wrist surgery. 2013 May:2(2):190-4. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1341409. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24436815]

Han SH, Hong IT, Kim WH. LCP distal ulna plate fixation of irreducible or unstable distal ulna fractures associated with distal radius fracture. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2014 Dec:24(8):1407-13. doi: 10.1007/s00590-014-1427-y. Epub 2014 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 24566964]

Kim JK, Kim JO, Koh YD. Management of Distal Ulnar Fracture Combined with Distal Radius Fracture. The journal of hand surgery Asian-Pacific volume. 2016 Jun:21(2):155-60. doi: 10.1142/S2424835516400075. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27454628]

Logan AJ, Lindau TR. The management of distal ulnar fractures in adults: a review of the literature and recommendations for treatment. Strategies in trauma and limb reconstruction. 2008 Sep:3(2):49-56. doi: 10.1007/s11751-008-0040-1. Epub 2008 Sep 3 [PubMed PMID: 18766429]

Daneshvar P, Chan R, MacDermid J, Grewal R. The effects of ulnar styloid fractures on patients sustaining distal radius fractures. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Oct:39(10):1915-20. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.05.032. Epub 2014 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 25135248]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMeena S, Sharma P, Sambharia AK, Dawar A. Fractures of distal radius: an overview. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2014 Oct-Dec:3(4):325-32. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25657938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRichards TA, Deal DN. Distal ulna fractures. The Journal of hand surgery. 2014 Feb:39(2):385-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.08.103. Epub 2014 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 24411292]

Ali M, Clark DI, Tambe A. Nightstick Fractures, Outcomes of Operative and Non-Operative Treatment. Acta medica (Hradec Kralove). 2019:62(1):19-23. doi: 10.14712/18059694.2019.41. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30931892]

Hermans K, Fransz D, Walbeehm-Hol L, Hustinx P, Staal H. Is a Parry Fracture-An Isolated Fracture of the Ulnar Shaft-Associated with the Probability of Abuse in Children between 2 and 16 Years Old? Children (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Jul 28:8(8):. doi: 10.3390/children8080650. Epub 2021 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 34438541]

Thomas BP, Sreekanth R. Distal radioulnar joint injuries. Indian journal of orthopaedics. 2012 Sep:46(5):493-504. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.101031. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23162140]

Ryznar E, Rosado N, Flaherty EG. Understanding forearm fractures in young children: Abuse or not abuse? Child abuse & neglect. 2015 Sep:47():132-9. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.02.008. Epub 2015 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 25765815]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMitrousias V, Amprazis V, Baltas C, Karachalios T. Isolated Salter-Harris Type II Fracture of the Distal Ulna. Cureus. 2021 Jun:13(6):e15552. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15552. Epub 2021 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 34277177]

Sammer DM, Shah HM, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. The effect of ulnar styloid fractures on patient-rated outcomes after volar locking plating of distal radius fractures. The Journal of hand surgery. 2009 Nov:34(9):1595-602. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.05.017. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19896004]

Moloney M, Farnebo S, Adolfsson L. Incidence of distal ulna fractures in a Swedish county: 74/100,000 person-years, most of them treated non-operatively. Acta orthopaedica. 2020 Feb:91(1):104-108. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2019.1686570. Epub 2019 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 31680591]

Meaike JJ, Kakar S. Management of Comminuted Distal Radius Fractures: A Critical Analysis Review. JBJS reviews. 2020 Aug:8(8):e2000010. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.20.00010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32960024]

Xu W, Ni C, Yu R, Gu G, Wang Z, Zheng G. Risk factors for distal radius fracture in postmenopausal women. Der Orthopade. 2017 May:46(5):447-450. doi: 10.1007/s00132-017-3403-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28258366]

Clesham K, Piggott RP, Sheehan E. Displaced Salter-Harris I fracture of the distal ulna physis. BMJ case reports. 2019 Aug 28:12(8):. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-230783. Epub 2019 Aug 28 [PubMed PMID: 31466954]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScheker LR, Babb BA, Killion PE. Distal ulnar prosthetic replacement. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2001 Apr:32(2):365-76, x [PubMed PMID: 11331548]

Kim JK, Koh YD, Do NH. Should an ulnar styloid fracture be fixed following volar plate fixation of a distal radial fracture? The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2010 Jan:92(1):1-6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01738. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20048089]

May MM, Lawton JN, Blazar PE. Ulnar styloid fractures associated with distal radius fractures: incidence and implications for distal radioulnar joint instability. The Journal of hand surgery. 2002 Nov:27(6):965-71 [PubMed PMID: 12457345]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSmall RF, Taqi M, Yaish AM. Radius and Ulnar Shaft Fractures. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491613]

Earle AS, Vlastou C. Crossed fingers and other tests of ulnar nerve motor function. The Journal of hand surgery. 1980 Nov:5(6):560-5 [PubMed PMID: 7430600]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAgarwal T, Agarwal V, Agarwal P, Thakur S, Bobba R, Sharma D. Assessment of collateral hand circulation by modified Allen's test in normal Indian subjects. Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2020 Jul-Aug:11(4):626-629. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2020.04.004. Epub 2020 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 32684700]

Ou Yang O, McCombe DB, Keating C, Maloney PP, Berger AC, Tham SKY. Ulnar-sided wrist pain: a prospective analysis of diagnostic clinical tests. ANZ journal of surgery. 2021 Oct:91(10):2159-2162. doi: 10.1111/ans.17169. Epub 2021 Aug 30 [PubMed PMID: 34459533]

Tay SC, Tomita K, Berger RA. The "ulnar fovea sign" for defining ulnar wrist pain: an analysis of sensitivity and specificity. The Journal of hand surgery. 2007 Apr:32(4):438-44 [PubMed PMID: 17398352]

Nakamura R, Horii E, Imaeda T, Nakao E, Kato H, Watanabe K. The ulnocarpal stress test in the diagnosis of ulnar-sided wrist pain. Journal of hand surgery (Edinburgh, Scotland). 1997 Dec:22(6):719-23 [PubMed PMID: 9457572]

Douma-den Hamer D, Blanker MH, Edens MA, Buijteweg LN, Boomsma MF, van Helden SH, Mauritz GJ. Ultrasound for Distal Forearm Fracture: A Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. PloS one. 2016:11(5):e0155659. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155659. Epub 2016 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 27196439]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceManz MH, Jensen KO, Allemann F, Simmen HP, Rauer T. If there is smoke, there must be fire - Isolated distal, non-displaced, intraarticular ulna fracture: A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2019:60():145-147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.06.009. Epub 2019 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 31226646]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceThomas R, Dyer GSM, Tornetta Iii P, Park H, Gujrathi R, Gosangi B, Lebovic J, Hassan N, Seltzer SE, Rexrode KM, Boland GW, Harris MB, Khurana B. Upper extremity injuries in the victims of intimate partner violence. European radiology. 2021 Aug:31(8):5713-5720. doi: 10.1007/s00330-020-07672-1. Epub 2021 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 33459857]

Boer BC, Vestering M, van Raak SM, van Kooten EO, Huis In 't Veld R, Vochteloo AJH. MR arthrography is slightly more accurate than conventional MRI in detecting TFCC lesions of the wrist. European journal of orthopaedic surgery & traumatology : orthopedie traumatologie. 2018 Dec:28(8):1549-1553. doi: 10.1007/s00590-018-2215-x. Epub 2018 Apr 26 [PubMed PMID: 29700613]

Hussain A, Nema SK, Sharma D, Akkilagunta S, Balaji G. Does operative fixation of isolated fractures of ulna shaft results in different outcomes than non-operative management by long arm cast? Journal of clinical orthopaedics and trauma. 2018 Mar:9(Suppl 1):S86-S91. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2017.12.004. Epub 2017 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 29628706]

Gauthier M, Beaulieu JY, Nichols L, Hannouche D. Ulna hook plate osteosynthesis for ulna head fracture associated with distal radius fracture. Journal of orthopaedics and traumatology : official journal of the Italian Society of Orthopaedics and Traumatology. 2022 Aug 16:23(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s10195-022-00658-3. Epub 2022 Aug 16 [PubMed PMID: 35972706]

Rampazzo A, Gharb BB, Brock G, Scheker LR. Functional Outcomes of the Aptis-Scheker Distal Radioulnar Joint Replacement in Patients Under 40 Years Old. The Journal of hand surgery. 2015 Jul:40(7):1397-1403.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2015.04.028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26095055]

Souer JS, Ring D, Matschke S, Audige L, Marent-Huber M, Jupiter JB, AOCID Prospective ORIF Distal Radius Study Group. Effect of an unrepaired fracture of the ulnar styloid base on outcome after plate-and-screw fixation of a distal radial fracture. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2009 Apr:91(4):830-8. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00345. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19339567]

Wysocki RW, Ruch DS. Ulnar styloid fracture with distal radius fracture. The Journal of hand surgery. 2012 Mar:37(3):568-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.08.035. Epub 2011 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 22018474]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLutsky KF, Lucenti L, Beredjiklian PK. Outcomes of Distal Ulna Fractures Associated With Operatively Treated Distal Radius Fractures. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2020 May:15(3):418-421. doi: 10.1177/1558944718812134. Epub 2018 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 30417702]

Handoll HH, Pearce P. Interventions for treating isolated diaphyseal fractures of the ulna in adults. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 Jun 13:2012(6):CD000523. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000523.pub4. Epub 2012 Jun 13 [PubMed PMID: 22696319]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAyalon O, Marcano A, Paksima N, Egol K. Concomitant Ulnar Styloid Fracture and Distal Radius Fracture Portend Poorer Outcome. American journal of orthopedics (Belle Mead, N.J.). 2016 Jan:45(1):34-7 [PubMed PMID: 26761916]

Geissler WB, Clark SM. Fragment-Specific Fixation for Fractures of the Distal Radius. Journal of wrist surgery. 2016 Mar:5(1):22-30. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571186. Epub 2016 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 26855832]

Wascher DC, Bulthuis L. Extremity trauma: field management of sports injuries. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2014 Dec:7(4):387-93. doi: 10.1007/s12178-014-9242-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25283054]