Introduction

Conjunctivochalasis (CCh) is an underdiagnosed and common condition characterized by loose, redundant, and non-edematous conjunctival folds typically located in the inferior bulbar conjunctiva. The term, which comes from the Greek “chalasis,” meaning to slacken, was first used by Hughes in 1942. CCh can cause a spectrum of symptoms, ranging from mild discomfort in the mild stages to tear outflow obstruction in the moderate stages and exposure keratopathy with subsequent visual loss in the severe stages.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of CCh has not been fully elucidated. Some studies have hypothesized that the condition may be secondary to the degradation of elastic fibers.[2][3] Elastic fibers are a key connective tissue component of the extracellular matrix and provide mechanical support and structure to the conjunctiva. It is thought that the repeated friction of the eyelids against the conjunctiva contributes to the breakdown of the elastic fibers and the development of the characteristic lid-parallel conjunctival folds (LIPCOF).[4] These folds can obstruct the tear drainage, shorten the fornices, and obliterate the tear meniscus and reservoir.[5][6] Other risk factors may exacerbate this process, including genetics, age, mechanical stress (e.g., contact lenses), inflammation, and ultraviolet light.[7][8][9][10]

Furthermore, the cumulative mechanical insults likely induce an inflammatory response and secondary conjunctival and Tenon capsule breakdown. The formation of the LIPCOF decreases tear outflow, leading to the build-up of inflammatory molecules on the ocular surface and activation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).[11] MMPs are proteins that degrade and remodel the extracellular matrix; hence would have detrimental effects on the conjunctiva in higher concentrations.

Epidemiology

CCh generally affects the older population and is therefore often regarded as a senile change. Numerous studies have described a proportionally higher prevalence of CCh with increasing age.[8][12] There is no gender predilection, although some studies have found higher grades of CCh and lower tear meniscus area in female patients. The majority of the epidemiological studies originate from China and demonstrate a high prevalence rate of total and clinically significant CCh (44% and 18%, respectively).[12] The incidence and prevalence have not been well studied in the United States; a small study conducted at an American Veterans Affairs hospital showed that a greater proportion of patients with CCh were of non-Hispanic ethnicity than those without the condition.[13]

Pathophysiology

Ocular inflammation plays an important role in the pathophysiology of CCh. Studies have reported a heightened expression of MMPs in cultured conjunctival fibroblasts in patients with CCh, in addition to an upregulation of inflammatory and oxidative stress markers in their tear profiles.[10][11] It is thought that the inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha, trigger the overexpression of MMPs in cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts.[14] The delayed tear clearance further aggravates this process, leading to oxidative damage of the ocular surface.[10][15]

Histopathology

Varying histological results have been reported, likely due to the large spectrum of disease severity. In CCh tissue, studies using microscopy found normal conjunctival epithelium, epithelial hyperplasia, and reduced intracellular cohesiveness.[15] Signs of elastosis or chronic non-granulomatous inflammation were also described in specimens of CCh. It is not clear whether there are inflammatory cells in the conjunctival folds.[16][17] The contradictory findings and absence of statistical difference in histopathological studies may suggest that the pathology of CCh may not lie in the conjunctival tissue itself but is likely linked to its loose adhesions.[18]

History and Physical

CCh can cause an array of symptoms, ranging from aggravation of a dry eye at the mild stage to disturbance of tear outflow at the moderate stage and exposure problems at the severe stage. Symptoms can be vague and comprise foreign body sensation, burning, pain, redness, epiphora, photophobia, and blurry vision, typically worsened during downgaze, blinking, or digital compression onto the globe.[19][20] It is thought that patients with nasal CCh were more affected with dry eye symptoms and experienced substantial negative impacts on quality of life.[13]

Evaluation

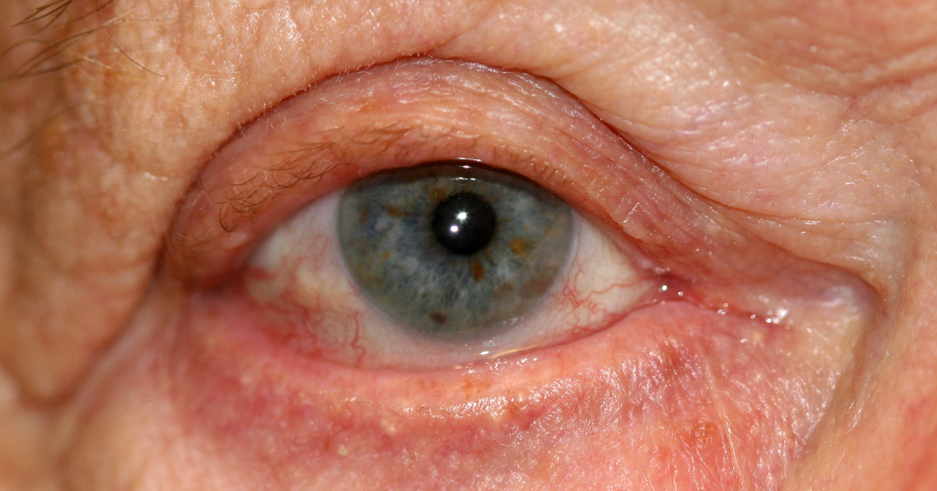

LIPCOF

CCh is typically bilateral and characterized by loose redundant conjunctival folds. It can involve any portion of the bulbar conjunctiva but generally is more prominent inferiorly. Slit-lamp examinations may confirm the LIPCOF, typically found over the lower lid. As the entity progresses, the redundant conjunctiva can shorten the fornices and mechanically obstruct the punctum.[20] The folds are more prominent when applying upward pressure on the lower lid and flattening upgaze or pulling the lower lid away from the globe. Finding the folds in superior CCh is more challenging; they can be seen with the downward pressure of the upper lid against the globe.

The depth of the fornices can be measured using the slit-lamp beam or devices such as the fornix depth measurer. Studies have shown that anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT) can aid in diagnosing and monitoring patients with CCh as the cross-sectional area of conjunctiva prolapsing can be measured.[21] Zhang et al. showed with anterior segment OCT that the conjunctiva in patients with CCh was thinner than normal controls.

Grading Systems

Multiple grading systems have been developed. Hoh et al.’s system comprise grades 0 to 3 depending on the number and height of folds.

- Grade 0 (no persistent fold)

- Grade 1 (a single, small fold)

- Grade 2 (two or more folds but not higher than the tear meniscus)

- Grade 3 (multiple folds and higher than the tear meniscus)[22]

Meller et al. proposed a new multiparameter system, which considers the location, height of the folds, punctal occlusion, and whether there are changes in downgaze and with digital pressure (Table 1). It has further been subclassified as T, M, and N if the folds are primarily located in the temporal, middle, or nasal part of the eyelid, respectively. The grading system has subsequently been widely used and adapted.[23]

TABLE 1: Meller et al.’s CCh grading system

|

LOCATION |

FOLDS VERSUS TEAR MENISCUS HEIGHT |

PUNCTAL OCCLUSION |

CHANGES IN DOWNGAZE |

CHANGES BY DIGITAL PRESSURE |

|

0: none 1: one location 2: two locations 3: whole lid |

A: < tear meniscus B: = tear meniscus C: > tear meniscus |

O+: nasal location with punctal occlusion O-: nasal location without punctal occlusion |

G⇑: height/extent of CCh increases in downgaze G⇔: no difference G⇓: height/extent of CCh decreases in downgaze |

P⇑: height/extent of CCh increases on digital pressure P⇔: no difference P⇓: height/extent of CCh decreases on digital pressure |

Eifrig developed a new grading system based on the degree of conjunctival rolling beneath the margin of the cornea when the patient is asked to look toward the midline (referred to as the ‘roll sign’) and the speed at which conjunctival tissue/vessels return to their primary position after blinking (‘blink sign’). Both roll and blink signs are graded from 1 to 4.[24]

Secondary Features

CCh is often associated with keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), with a higher prevalence of KCS in patients with severe CCh. Therefore, additional tests such as Schirmer, tear break-up time, fluorescein staining, and clearance rate are critical. In isolated CCh cases, a discrete punctate or linear staining can be seen on the mucosal aspect of the lid margin near the redundant conjunctiva, which is different from the exposure pattern seen in patients with KCS. Although not readily available, an ocular surface interferometer can also be used to monitor changes in lipid layer thickness in patients with CCh.[25]

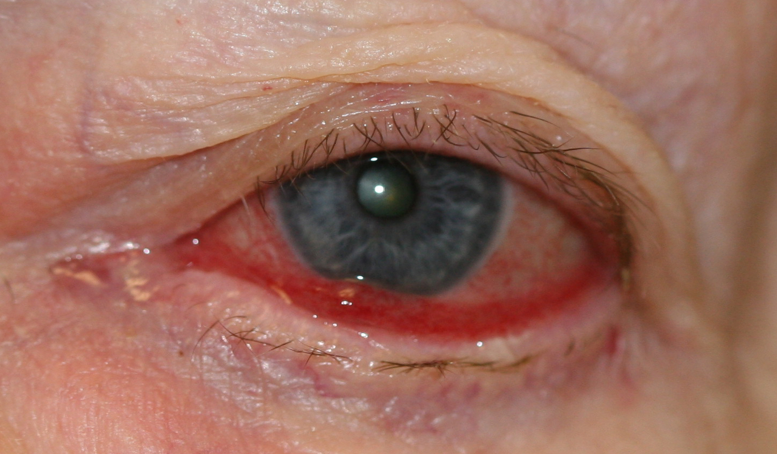

Other characteristic signs comprise subconjunctival hemorrhage (due to vessels in loose conjunctiva prone to rupture when blinking), swollen puncta, and anterior migration of the mucocutaneous junction (likely secondary to the delayed clearance of inflammatory proteins).[20] Furthermore, it is important to confirm whether there is any evidence of lagophthalmos on the blink, gentle, and forced closure.[26]

Some studies have also found a correlation between the presence of a pinguecula and the severity of CCh in the same conjunctival area.[27] The causative mechanism is unclear but has been speculatively attributed to confounding risk factors such as age and UV radiation. In severe cases, the development of corneal Dellen has also been described. Eyelid disorders, including meibomian gland dysfunction, floppy eyelid syndrome, entropion, often co-exist with CCh and can exacerbate the inflammatory process and development of the characteristic folds.[28]

Treatment / Management

For asymptomatic CCH, no treatment is necessary. In mild to moderate cases, topical drops can tackle chemosis and inflammation. As mentioned previously, the presence of CCh exhibits a strong positive predictive value in the diagnosis of KCS. Lubricants, including artificial tears and gels, can, therefore, provide symptomatic relief and stabilize the tear film. It is thought that certain ingredients in artificial tears (particularly isotonic glycerol and sodium hyaluronate) can dampen disease severity.[29]

Corticosteroids may address the chemosis and inflammation but may require long periods of use, and antihistamine drops can decrease any rubbing/mechanical insults. A study demonstrated a subjective and objective improvement of dry eye symptoms in CCh following a 3-week course of topical methylprednisolone.[30](B3)

Medical treatment may not be sufficient. Other approaches to tighten the redundant conjunctiva have been trialed with varying success rates (Table 2). These include conjunctival excision, cauterization, scleral fixation of the conjunctiva, conjunctival ligation, laser conjunctivoplasty, and radio-wave electrosurgery with or without tissue grafting (e.g., amniotic membrane).[31][32][33][34](B2)

Table 2: Examples of surgical procedures used to correct CCh with respective advantages and disadvantages

|

Technique |

Advantage |

Disadvantage |

|

Conjunctival cauterization |

Reduces operating time (no sutures needed), shrinks redundant folds, decreases the risk of motility problems/scar formation, possible improved scleral fixation.

|

Reserved for mild to moderate cases, repeat procedures may be necessary |

|

Excision of conjunctiva |

Removes redundant conjunctiva, reduces blink-associated microtrauma, reduces interference with tear meniscus. |

Over-resection -> fornix shortening, cicatricial entropion, limitation of ocular movement, suture-related complications (e.g., granuloma), secondary lymphangiectasia, prolonged postoperative recovery. |

|

Excision of conjunctiva with amniotic membrane graft |

As above + decreases the risk of fornix shortening |

Focal conjunctival inflammation, scar formation, suture related complications |

|

Scleral fixation of conjunctiva |

Strengthens adhesions to the sclera, reinforces the Tenon layer, reduces the risk of fornix shortening/ocular motility complications. |

Surgically challenging, suture-related complications |

|

Laser conjunctivoplasty, high-frequency radio-wave electrosurgery |

Reduces operating time, shrinks redundant folds, less invasive |

Not readily available, chemosis, hyperemia, and mild subconjunctival hemorrhage |

|

Recession of conjunctiva with amniotic membrane |

Removes redundant conjunctiva, reduces blink associated microtrauma, reduces interference with tear meniscus, restore tear reservoir |

Higher cost if amniotic membrane graft used |

The majority of these procedures involve excising or resecting the conjunctiva and may be effective as they relieve the mechanical obstruction. They do not, however, tackle fornix reconstruction and can cause scarring or relapses of the condition. Conjunctival recession is thought to be more effective as it restores the fornix tear reservoir.[5] Furthermore, the use of fibrin glue can decrease operating time and suture-related complications.[35](B2)

Important surgical steps involve:

- Recession of conjunctiva and anchoring it from the limbus

- removal of degenerated Tenon capsule

- replacement of the Tenon and the conjunctival tissue by amniotic membrane grafts to possibly decrease pain and hasten recovery

Differential Diagnosis

Due to the variable symptoms, it is important to rule out other conditions which cause tear flow obstruction and tear film instability, such as lid laxity or malposition disorders (e.g., ectropion, entropion, and floppy eyelid syndrome), trichiasis, punctal stenosis, conjunctivitis (viral/allergic) and nasolacrimal obstruction. A thorough history and physical examination will help differentiate CCh from other diseases that may generate similar symptoms.

In CCh, the symptoms worsen in downgaze and frequent blinking (because the folds increase or spread). In contrast, patients with dry eyes have worsening symptoms when looking up (e.g., at a computer), as the interpalpebral exposure zone widens and also improves with increased blinking. Superior CCh is often misdiagnosed as superior limbic keratitis (SLK). Clinical features such as micropapillary reaction in the upper tarsal conjunctiva, keratitis, and corneal erosions point towards the diagnosis of SLK, in addition to the presence of increased inflammation (e.g., hyperemia, eyelid edema).

Prognosis

CCh typically has a good prognosis with the correct treatment. Diagnosis is, however, often missed or delayed. Surgical management may be needed in symptomatic patients who do not respond to initial medical treatment. Studies have shown significant improvement in dry eye symptoms and signs following conjunctival recession with amniotic grafts, thus indicating that more attention may be warranted for the early diagnosis of this condition.[34][35]

Complications

Surgical complications are uncommon but include scarring, cicatricial entropion, retraction of the lower fornix, restricted motility, and corneal problems.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should be educated regarding lifestyle changes, particularly if CCh is associated with blepharitis and KCS, including avoidance of exacerbating factors (e.g., fans, air conditioners, heating vents, use of digital devices), diet change (low caffeine/alcohol intake, supplementation of fatty acids) and lid care. A recent study showed that the quality of life of patients with CCh was strongly determined by their tear-film instability and increased friction during blinking.[36] All treatment options, including conservative and surgical options, should be thoroughly discussed.

Pearls and Other Issues

- To look for the LIPCOF and examine the fornices in all patients presenting with ocular irritation or epiphora.

- Fornix reconstruction is the key to surgical success.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with CCh are often misdiagnosed; hence coordination between the optician, ophthalmic nurses, ophthalmologist, and surgeon is critical for prompt diagnosis and management. CCh can be associated with ocular surface diseases, which should be treated before any surgical intervention. Effective treatment involves surgical reconstruction of the tear meniscus as well as the reservoir.

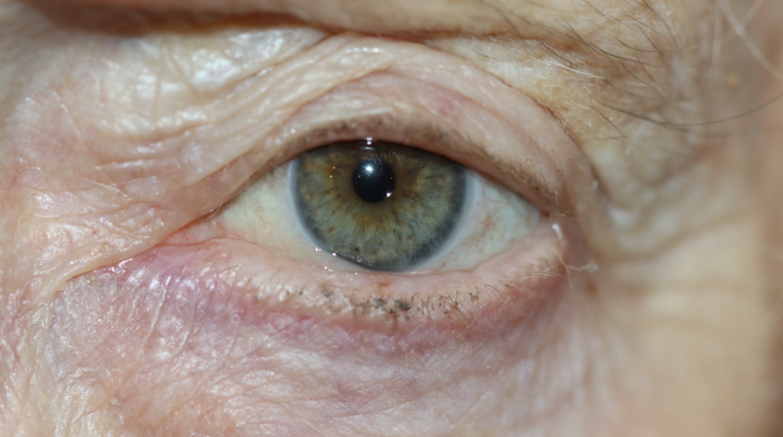

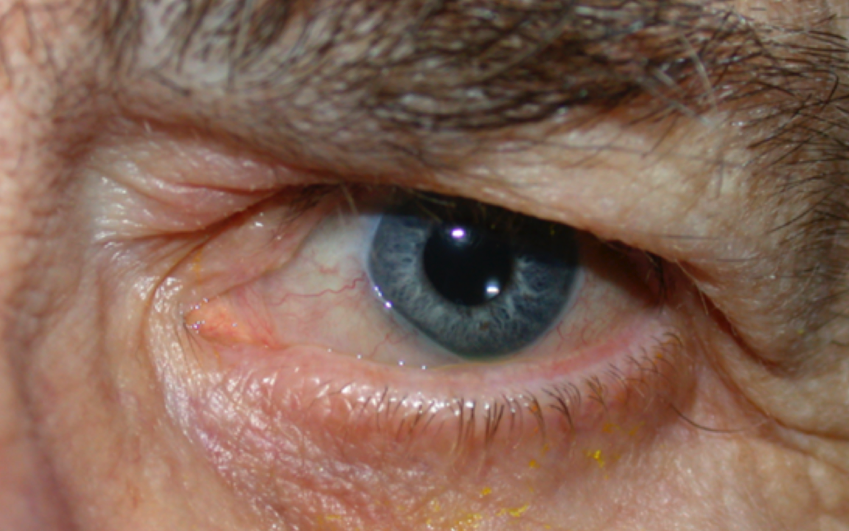

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Meller D,Tseng SC, Conjunctivochalasis: literature review and possible pathophysiology. Survey of ophthalmology. 1998 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 9862310]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGan JY,Li QS,Zhang ZY,Zhang W,Zhang XR, The role of elastic fibers in pathogenesis of conjunctivochalasis. International journal of ophthalmology. 2017; [PubMed PMID: 28944209]

Watanabe A,Yokoi N,Kinoshita S,Hino Y,Tsuchihashi Y, Clinicopathologic study of conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2004 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 15084864]

Huang Y,Sheha H,Tseng SC, Conjunctivochalasis interferes with tear flow from fornix to tear meniscus. Ophthalmology. 2013 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 23583167]

Cheng AM,Yin HY,Chen R,Tighe S,Sheha H,Zhao D,Casas V,Tseng SC, Restoration of Fornix Tear Reservoir in Conjunctivochalasis With Fornix Reconstruction. Cornea. 2016 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 26890668]

Xiang M,Zhang W,Wen H,Mo L,Zhao Y,Zhan Y, Comparative transcriptome analysis of human conjunctiva between normal and conjunctivochalasis persons by RNA sequencing. Experimental eye research. 2019 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 30999002]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFrancis IC,Chan DG,Kim P,Wilcsek G,Filipic M,Yong J,Coroneo MT, Case-controlled clinical and histopathological study of conjunctivochalasis. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2005 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 15722309]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMimura T,Yamagami S,Usui T,Funatsu H,Mimura Y,Noma H,Honda N,Amano S, Changes of conjunctivochalasis with age in a hospital-based study. American journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 18775527]

Mimura T,Usui T,Yamamoto H,Yamagami S,Funatsu H,Noma H,Honda N,Fukuoka S,Amano S, Conjunctivochalasis and contact lenses. American journal of ophthalmology. 2009 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 19403112]

Wang Y,Dogru M,Matsumoto Y,Ward SK,Ayako I,Hu Y,Okada N,Ogawa Y,Shimazaki J,Tsubota K, The impact of nasal conjunctivochalasis on tear functions and ocular surface findings. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 17916317]

Li DQ,Meller D,Liu Y,Tseng SC, Overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 by cultured conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts. Investigative ophthalmology [PubMed PMID: 10670469]

Zhang X,Li Q,Zou H,Peng J,Shi C,Zhou H,Zhang G,Xiang M,Li Y, Assessing the severity of conjunctivochalasis in a senile population: a community-based epidemiology study in Shanghai, China. BMC public health. 2011 Mar 31; [PubMed PMID: 21453468]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChhadva P,Alexander A,McClellan AL,McManus KT,Seiden B,Galor A, The impact of conjunctivochalasis on dry eye symptoms and signs. Investigative ophthalmology [PubMed PMID: 26024073]

Meller D,Li DQ,Tseng SC, Regulation of collagenase, stromelysin, and gelatinase B in human conjunctival and conjunctivochalasis fibroblasts by interleukin-1beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Investigative ophthalmology [PubMed PMID: 10967046]

Ward SK,Wakamatsu TH,Dogru M,Ibrahim OM,Kaido M,Ogawa Y,Matsumoto Y,Igarashi A,Ishida R,Shimazaki J,Schnider C,Negishi K,Katakami C,Tsubota K, The role of oxidative stress and inflammation in conjunctivochalasis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2010 Apr [PubMed PMID: 20019361]

Hashemian H,Mahbod M,Amoli FA,Kiarudi MY,Jabbarvand M,Kheirkhah A, Histopathology of Conjunctivochalasis Compared to Normal Conjunctiva. Journal of ophthalmic & vision research. 2016 Oct-Dec [PubMed PMID: 27994801]

Yokoi N,Komuro A,Nishii M,Inagaki K,Tanioka H,Kawasaki S,Kinoshita S, Clinical impact of conjunctivochalasis on the ocular surface. Cornea. 2005 Nov [PubMed PMID: 16227820]

Zhang XR,Cai RX,Wang BH,Li QS,Liu YX,Xu Y, [The analysis of histopathology of conjunctivochalasis]. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chinese journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 14989959]

Balci O, Clinical characteristics of patients with conjunctivochalasis. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2014; [PubMed PMID: 25210435]

Di Pascuale MA,Espana EM,Kawakita T,Tseng SC, Clinical characteristics of conjunctivochalasis with or without aqueous tear deficiency. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2004 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 14977775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGumus K,Crockett CH,Pflugfelder SC, Anterior segment optical coherence tomography: a diagnostic instrument for conjunctivochalasis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2010 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 20869039]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHöh H,Schirra F,Kienecker C,Ruprecht KW, [Lid-parallel conjunctival folds are a sure diagnostic sign of dry eye]. Der Ophthalmologe : Zeitschrift der Deutschen Ophthalmologischen Gesellschaft. 1995 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 8563428]

Zhang XR,Zou HD,Li QS,Zhou HM,Liu B,Han ZM,Xiang MH,Zhang ZY,Wang HM, Comparison study of two diagnostic and grading systems for conjunctivochalasis. Chinese medical journal. 2013 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 23981623]

Eifrig DE, Grading conjunctivochalasis. Survey of ophthalmology. 1999 Jul-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 10466593]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChan TC, Ye C, Ng PK, Li EY, Yuen HK, Jhanji V. Change in Tear Film Lipid Layer Thickness, Corneal Thickness, Volume and Topography after Superficial Cauterization for Conjunctivochalasis. Scientific reports. 2015 Jul 17:5():12239. doi: 10.1038/srep12239. Epub 2015 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 26184418]

Acera A,Suárez T,Rodríguez-Agirretxe I,Vecino E,Durán JA, Changes in tear protein profile in patients with conjunctivochalasis. Cornea. 2011 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 20861728]

Mimura T,Mori M,Obata H,Usui T,Yamagami S,Funatsu H,Noma H,Amano S, Conjunctivochalasis: associations with pinguecula in a hospital-based study. Acta ophthalmologica. 2012 Dec [PubMed PMID: 21518307]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHashemi H,Rastad H,Emamian MH,Fotouhi A, Conjunctivochalasis and Related Factors in an Adult Population of Iran. Eye [PubMed PMID: 28346280]

Kiss HJ,Németh J, Isotonic Glycerol and Sodium Hyaluronate Containing Artificial Tear Decreases Conjunctivochalasis after One and Three Months: A Self-Controlled, Unmasked Study. PloS one. 2015 [PubMed PMID: 26172053]

Prabhasawat P,Tseng SC, Frequent association of delayed tear clearance in ocular irritation. The British journal of ophthalmology. 1998 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 9797670]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOtaka I,Kyu N, A new surgical technique for management of conjunctivochalasis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2000 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 10704560]

Ji YW,Seong H,Lee S,Alotaibi MH,Kim TI,Lee HK,Seo KY, The correction of conjunctivochalasis using high-frequency radiowave electrosurgery improves dry eye disease. Scientific reports. 2021 Jan 28; [PubMed PMID: 33510304]

Marmalidou A,Palioura S,Dana R,Kheirkhah A, Medical and surgical management of conjunctivochalasis. The ocular surface. 2019 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 31009751]

Meller D,Maskin SL,Pires RT,Tseng SC, Amniotic membrane transplantation for symptomatic conjunctivochalasis refractory to medical treatments. Cornea. 2000 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 11095053]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKheirkhah A,Casas V,Blanco G,Li W,Hayashida Y,Chen YT,Tseng SC, Amniotic membrane transplantation with fibrin glue for conjunctivochalasis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2007 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 17659969]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKomuro A,Yokoi N,Kato H,Sonomura Y,Sotozono C,Kinoshita S, The Relationship between Subjective Symptoms and Quality of Life in Conjunctivochalasis Patients. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland). 2021 Jan 27; [PubMed PMID: 33513725]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence