Introduction

Anesthesia breathing systems serve as a conduit to deliver anesthetic and other gases to a patient. Various designs of breathing systems have been created to serve this function. One method of classifying anesthesia breathing systems is based on how gas flows: open, semi-open, semi-closed, and closed systems.[1] This classification method is dictated by the physical characteristics of each system. This article will review this classification method, the various anesthesia breathing systems, and the clinical significance of each system.

Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Function

Anesthesia breathing systems function to deliver inhaled gases to patients. These most often include a mixture of fresh gas (oxygen, air) and anesthetic gases, both volatile agents (e.g., isoflurane) and non-volatile agents (nitrous oxide). Anesthesia breathing systems also function to eliminate exhaled gases (including carbon dioxide) from the patient. One method of classifying anesthesia breathing systems is based on the presence or absence of specific physical and functional characteristics of each system. However, it is important to note that this is not the only method of classifying breathing systems.[2]

- Open breathing systems have no reservoir breathing bag, no functional rebreathing of exhaled gases, no tubing, and no valves. These systems include insufflation and open-drop anesthesia.

- Semi-open breathing systems have a reservoir breathing bag, no functional re-breathing of exhaled gases, and have high fresh gas flows. These include Mapleson breathing systems.

- Semi-closed breathing systems have a reservoir breathing bag, partial re-breathing of exhaled gases, unidirectional valves, neutralizing carbon dioxide, and low fresh gas flows. These include circle systems with an adjustable pressure-limiting valve (APL valve) that is at least partially open.

- Closed breathing systems have a reservoir breathing bag, total rebreathing of exhaled gases, unidirectional valves, and neutralize carbon dioxide. These include circle systems with the APL valve closed.

Open-Drop Anesthesia

The open-drop anesthesia breathing system is no longer used in modern medicine but is of historical significance and maybe occasionally used in developing countries.[3][4] The Schimmelbusch mask, a wired mask invented by Curt Schimmelbusch in 1889 and used into the 1950s, is one of the simplest forms of an anesthesia breathing system. This system secures gauze to a wired mask, and liquid volatile anesthetics (ether, chloroform, or halothane) are dropped onto the gauze. As the patient inhales through the mask, air will pass through the gauze, vaporize the anesthetic liquid, and deliver high concentrations of anesthetic to the patient. In this system, there is no rebreathing of exhaled gases. The benefit of the system is the simplicity of setup and limited equipment.

Insufflation

The insufflation breathing system is a technique used to blow anesthetic gases through a mask across a patient’s face without the mask being in direct contact with the patient. This breathing system is most commonly used with pediatric patients when placing a face mask directly on the child’s face may be difficult or resisted by the patient.[5] High flow insufflation has also been used in ophthalmic surgery.[6] In this system, especially if the gas flow is high enough, there is virtually no rebreathing of exhaled gases.

Mapleson Circuits

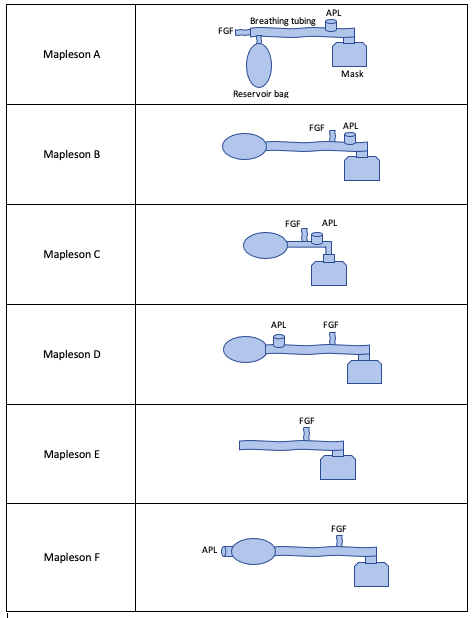

In 1954, William Mapleson designated varying arrangements of breathing system components (masks, breathing tubes, fresh gas flow inlets, adjustable pressure-limiting valves, and reservoir bags) as Mapleson A-E circuits.[7]

A mask is placed over a patient’s face to connect the patient to the system in these systems. These systems can also be connected to laryngeal mask airways or endotracheal tubes. The system typically has corrugated tubing that connects the mask or airway to the other system components, including a reservoir bag used to generate positive-pressure ventilation. Mixed gases are delivered to the system by a fresh gas flow (FGF) inlet. As anesthetic and fresh gases are delivered to the system, pressure will build if the gas inflow is greater than inspired volumes. Thus, the system also contains an adjustable pressure-limiting valve (APL valve) which allows gases to exit the breathing system. An open APL valve is utilized during spontaneous ventilation to prevent pressure buildup and allow all expired gases to exit the system. As the valve is partially closed, gas is limited from exiting the system, permitting positive-pressure ventilation generated within the reservoir bag. Assuming fresh-gas inflow is adequate, an open APL valve will vent exhaled gas before inspiration to prevent rebreathing in these systems.

The varying arrangements of Mapleson circuits are discussed briefly (see Figure. Mapleson Circuits).[7] Each circuit arrangement will be described from furthest to closest to the patient.

Mapleson A: Arranged as FGF inlet, reservoir bag, APL valve, mask.

- In this circuit, because the reservoir bag is between the FGF inlet valve and the APL valve, expired gas from the patient may re-enter the system and fill the reservoir bag during controlled ventilation (i.e., when the APL valve is partially closed) if the fresh gas inflow is not adequate (defined as two to three times minute ventilation in this system). However, this is the most efficient system for spontaneous breathing as the FGF must only be equal to a patient’s minute ventilation to prevent rebreathing.

Mapleson B: Arranged as reservoir bag, FGF inlet, APL valve, mask.

- In this circuit, the FGF inlet is closer to the APL valve, which helps prevent the rebreathing concern in the Mapleson A circuit as above during controlled ventilation.

Mapleson C: Arranged as reservoir bag, FGF inlet, APL valve, mask.

- In this circuit, the arrangement is the same as the Mapleson B circuit. However, this circuit is shorter as it does not contain elongated corrugated tubing. This circuit also has the FGF inlet close to the APL valve to aid in preventing rebreathing.

Mapleson D: Arranged as reservoir bag, APL valve, FGF inlet, and mask.

- In this circuit, the arrangement interchanges the FGF inlet and APL valve of the Mapleson A circuit. This system prevents rebreathing by directing FGF towards the APL valve rather than towards the patient during exhalation. Therefore, in this circuit, which is also true for circuits E and F, two to three times minute ventilation must be used to prevent rebreathing during spontaneously breathing. In contrast, only one to two times the minute ventilation flow is required during controlled breathing. Note that this is the opposite of the Mapleson A circuit.

Mapleson E: Arranged as corrugated tubing, FGF inlet, and mask.

- In this circuit, there is no reservoir bag and no APL valve. Given the inability to alter the pressure of the circuit, this is ideal for spontaneously ventilating neonates or pediatric patients where low-pressure ventilation is desired.[7] The system prevents rebreathing, similar to the Mapleson D circuit.

Mapleson F: Arranged as APL valve directly connected to reservoir bag, corrugated tubing, FGF inlet, and mask.

- The system prevents rebreathing similarly to Mapleson D by directing FGF towards the APL valve.

The Circle System

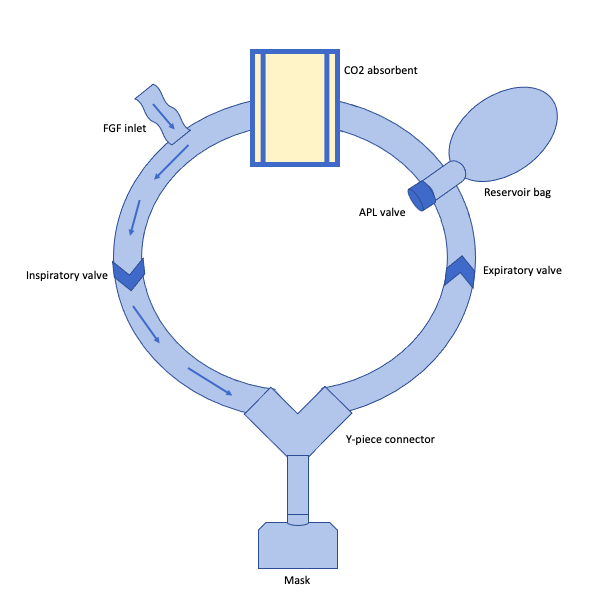

The circle system is the most clinically relevant breathing system in developed countries (see Figure. Circle System). This system has more components than a Mapleson circuit that are arranged in a circular apparatus, and the system has a greater capacity to prevent rebreathing. In addition to a reservoir bag, tubing, APL valve, and FGF inlet, this system also has a carbon dioxide (CO2) absorber, unidirectional expiratory and inspiratory valves, and a Y-piece connector.

The circle system is arranged so that the FGF inlet delivers gas to the inspiratory breathing tubing (containing a unidirectional valve), which is connected to a Y-piece. Unidirectional valves are placed near the patient to prevent backflow in the circuit, and the Y-piece is connected to the patient’s mask. As the patient exhales, exhaled gas goes through the mask, into the Y-piece, and out through the expiratory breathing tubing (which also contains a unidirectional valve). This expiratory breathing tubing is connected to a reservoir bag and APL valve. Beyond these components is a carbon dioxide (CO2) absorber.[1]

When using a circle system, a patient will rebreathe expired alveolar gas. This gas, which has been heated and humidified by airway structures during respiration, also contains expired anesthetic and CO2. Thus, a benefit of a circle system is that it conserves heat, humidity, and anesthetic. However, the expired CO2 must be removed from the system. This is the function of the CO2 absorber. Exhaled CO2 from a patient combines with water to form carbonic acid. The CO2 absorber contains hydroxide salts (strong bases) that neutralize carbonic acid through a chemical reaction that produces additional heat, humidification, and calcium carbonate. Soda-lime is one of the most common types of hydroxide salt absorbents and contains water, calcium hydroxide, sodium hydroxide, and potassium hydroxide.[8]

Absorbents contain salt granules (sizes of approximately 4 to 8 mesh) that undergo a color change from the chemical reaction between these compounds and CO2. When approximately 50 to 70% of absorbent granules have changed color (a pH indicator dye that is typically a purple color known as ethyl violet but may vary based on the manufacturer of the absorbent) may indicate absorbent exhaustion requiring canister replacement to avoid rebreathing.[9]

Resuscitation Breathing Systems

Resuscitation breathing systems (including brand-name AMBU bags or bag-mask units) are simple and portable systems used in emergency scenarios or when transporting patients in need of ventilation.[10] These systems have the ability to deliver nearly 100% oxygen to a patient. The system contains an inlet nipple (open to the air or connected to an oxygen source) connected through an intake valve to a ventilation bag. The ventilation bag, which is self-inflating based on inherent material memory, then delivers gas to the patient’s mask or invasive airway via a patient valve. An intake valve attached to the ventilation bag closes when the bag is compressed, allowing for positive-pressure ventilation. Rebreathing is prevented in this system by venting exhaled gas through an exhalation port in the patient valve, where an additional PEEP valve can be added to allow for positive end-expiratory pressure.[10][11]

Clinical Significance

Given the circle system is the most commonly used breathing system in the United States, its significance will be discussed here. Advantages of this breathing system include good control of anesthetic depth, ability to scavenge exhaled gasses, lower requirements of fresh gas flow due to the CO2 absorber, conservation of heat and humidity, and minimal contribution to anatomic dead space as only components distal to and including the Y-piece contribute to dead space. Of note, the CO2 absorber may break down volatile anesthetics into clinically measurable concentrations of carboxyhemoglobin by generating carbon monoxide. This reaction is of greatest risk when using desflurane and CO2 absorbents with high quantities of strong bases such as potassium hydroxide (KOH) or sodium hydroxide (NaOH).[8][12][13]

Additionally, in rat and non-human primate studies, sevoflurane degradation by the absorbent has produced a byproduct called compound A. Compound A has been shown to cause nephrotoxicity in these animal studies, but the same effects have never been demonstrated in humans.[14][15] Still, to prevent the formation of compound A, it is recommended that fresh gas flows of at least 2L/min are used when using sevoflurane gas.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Having a thorough understanding of the complexity of anesthesia breathing systems should be perfected by all anesthetists and members of the anesthesia care team. Attending anesthesiologists, anesthesia residents, certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNA), certified anesthesiologist assistants (CAA), and anesthesia technologists/technicians should be knowledgeable regarding the function, performance, technique for use, and disadvantages for each system.

Each of these anesthesia providers must be held accountable for this knowledge as anesthesia is consistently delivered to patients by a team of providers rather than individual clinicians. At any point in delivering an anesthetic, all anesthetists should have a comprehensive understanding of the anesthesia breathing system to ensure proper function, troubleshoot errors, and employ alternative breathing systems as needed to guarantee the safety of each patient is made a priority. This is vital to enhancing patient-centered care and improving perioperative medicine outcomes for patients.

Media

References

Conway CM. Anaesthetic breathing systems. British journal of anaesthesia. 1985 Jul:57(7):649-57 [PubMed PMID: 3925973]

Baum J. [Anesthesia systems]. Der Anaesthesist. 1987 Aug:36(8):393-9 [PubMed PMID: 3310726]

Lo R. The Schimmelbusch mask. Hong Kong medical journal = Xianggang yi xue za zhi. 2014 Dec:20(6):560-1 [PubMed PMID: 25632423]

Maltby JR,Malla DS,Dangol H, Open drop ether anaesthesia for caesarean section: a review of 420 cases in Nepal. Canadian Anaesthetists' Society journal. 1986 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 3768769]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTalyshinskiĭ AM, Baĭtiakov VV, Kosenko VF. [Use of insufflation method of inhalation anesthesia in tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in children]. Vestnik otorinolaringologii. 1971 Jul-Aug:33(4):76-80 [PubMed PMID: 5112401]

Tautenhahn E. [Insufflation anesthesia in ophthalmic surgery]. Klinische Monatsblatter fur Augenheilkunde. 1972 Dec:161(6):703-5 [PubMed PMID: 4655902]

Kaul TK, Mittal G. Mapleson's Breathing Systems. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2013 Sep:57(5):507-15. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.120148. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24249884]

Keijzer C, Perez RS, de Lange JJ. Carbon monoxide production from desflurane and six types of carbon dioxide absorbents in a patient model. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2005 Jul:49(6):815-8 [PubMed PMID: 15954965]

Parthasarathy S. The closed circuit and the low flow systems. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2013 Sep:57(5):516-24. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.120149. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24249885]

Khoury A, Hugonnot S, Cossus J, De Luca A, Desmettre T, Sall FS, Capellier G. From mouth-to-mouth to bag-valve-mask ventilation: evolution and characteristics of actual devices--a review of the literature. BioMed research international. 2014:2014():762053. doi: 10.1155/2014/762053. Epub 2014 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 24971346]

Bucher JT, Vashisht R, Ladd M, Cooper JS. Bag-Valve-Mask Ventilation. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28722953]

Wissing H, Kuhn I, Warnken U, Dudziak R. Carbon monoxide production from desflurane, enflurane, halothane, isoflurane, and sevoflurane with dry soda lime. Anesthesiology. 2001 Nov:95(5):1205-12 [PubMed PMID: 11684991]

Berry PD, Sessler DI, Larson MD. Severe carbon monoxide poisoning during desflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 1999 Feb:90(2):613-6 [PubMed PMID: 9952168]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKharasch ED. [Compound A: toxicology and clinical relevance]. Der Anaesthesist. 1998 Nov:47 Suppl 1():S7-10 [PubMed PMID: 9893874]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFrink EJ Jr, Green WB Jr, Brown EA, Malcomson M, Hammond LC, Valencia FG, Brown BR Jr. Compound A concentrations during sevoflurane anesthesia in children. Anesthesiology. 1996 Mar:84(3):566-71 [PubMed PMID: 8659785]