Cognitive Decline and Driving Evaluation in the Older Population

Cognitive Decline and Driving Evaluation in the Older Population

Introduction

Cognitive decline can be described as a gradual or sudden loss of thinking abilities such as learning, paying attention and remembering past events/details.This is more commonly seen in the older adults with dementia.[1] When taking care of patients with dementia (PWD), it is important to assess the patient’s fitness to drive. Patients with dementia have a 2-8x increased risk of motor vehicle accidents compared to similarly aged drivers without dementia, yet many are never counseled on driving safety.[2]

Driving safety assessment is a sensitive discussion that is often delayed or forgone altogether because of physician reluctance, patient refusal, or caretaker preference. Physicians often are not formally trained on how to conduct these conversations and seldom do not conduct the assessment. Driving is integral to a patient’s independence, so discussions of driving fitness may be met with emotional resistance, and patients may not recognize or admit their deficits.[3]

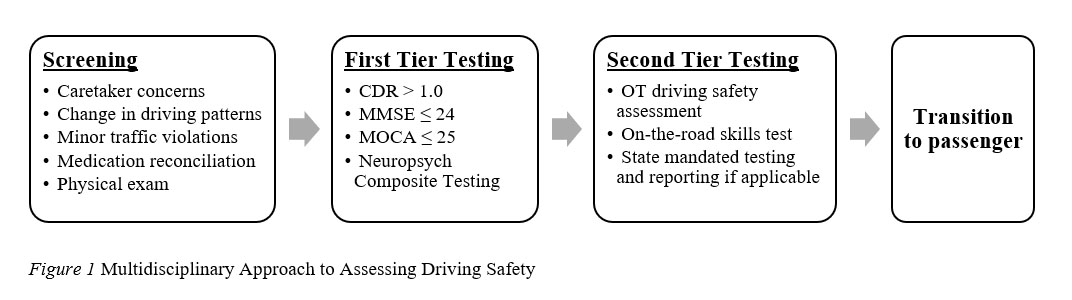

The true extent of driving impairment may be minimized by caretakers who either do not want to admit the progression of their loved one’s disease or do not want to take on additional driving responsibilities.[4] Despite these barriers, driver safety assessment is an important public health and medicolegal issue and should be familiar to all healthcare professionals. See Driving Screening Flowchart below:

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Driving a vehicle is a complex task that involves several different domains including cognitive, visual and motor skills. These can present as age-related changes, even in older adults with health aging[5]. These changes include the decline in neuromuscular and musculoskeletal function, with reduced muscle strength and decreased coordination and motor control[6].

Unlike other activities of daily living, driving is unpredictable and requires attention to many simultaneous audiovisual inputs.[7] Drivers must be able to understand new traffic patterns and react quickly to their surroundings. They must also be able to process the symbols on their dashboard and the buttons to operate the car while also paying attention to the signage on the road. Older adult drivers, even without dementia, may find this multitasking difficult, as many already have chronic medical illnesses, physical disabilities, and the compounded effects of polypharmacy.[4] The added complication of cognitive impairment makes driving an even far greater challenge for patients with dementia. Analyses of errors made by drivers with dementia show significant difficulties with turning, lane positioning, and identifying traffic signs. Drivers with dementia are more likely to get lost or drive below the speed limit, which may result in road traffic accidents.[8]

Regardless of the type, neurocognitive disorders can cause deficits in attention, insight, and judgment. Patients have greater difficulty integrating information to make complex executive decisions.[7] Deficits such as apraxia may impair their ability to execute tasks critical to driving, such as timely application of the brakes or steering away from obstructions on the road. Frontotemporal dementia may lead to an increase in aggressive, risk-taking driving.[8] Patients with visuospatial deficits may miscalculate distances or have difficulties with parking in small spaces. In addition to these functional cognitive deficiencies, patients with dementia often have neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as anxiety, paranoia, and lack of insight into their illness.[9] Their motor reactivity may be slower, and their coordination and balance may also be impaired.[10] It is also noted that low education level and reduced cognition level are conditions that were predictors for loss of vehicular driving license[11].

Clinical Significance

Dementia is a progressive illness, and not all patients with dementia experience the same deficits. In fact, many patients with mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia still have the ability to operate a vehicle safely. However, an analysis of this population of patients with a clinical dementia rating scale of 0.5-1.0 showed on-road testing failure in 13% of the participants.[8] This suggests that even patients who report no problems with driving may have subtle impairment of driving skills and could benefit from driving fitness assessments. Early communication about anticipated driving difficulties allows the patient and family to be more cognizant of functional decline. Other symptoms that suggest a patient needs a driving assessment include changes in driving habits, preferring to take familiar roads only, minor vehicle accidents, and parking citations.[3] Often, collateral information from caretakers plays a key role in determining any concerns that the patient may not have noticed.

Assessing fitness to drive requires a multifactorial approach and a thorough cognitive assessment, and multiple objective scales and tests are used for evaluation.[3] Many organizations, such as the American Medical Association and the American Academy of Neurology, have proposed guidelines for evaluating driving safety, and these parameters often involve specific screening variables.

The most important factor is the severity of dementia, typically assessed with the Clinical Dementia Rating(CDR) scale. Patients with CDR >1.0 should be assessed for driving safety, as this is the only screening test that carries level A evidence of utility.[12][13][14] Forty-five percent of drivers with CDR 0.5 to 1.0 passed on-road driving tests but showed a cognitive decline in function in 6 months. As such, it is recommended to re-evaluate these patients with mild dementia every 3 to 6 months.[8][15]

A low cognitive testing performance often correlates with a patient’s inability to pass roadside driving tests. However, there is no clear pattern of regression. The 2010 AAN practice parameter for evaluating and managing driving risk in dementia suggested that patients with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤ of 24 are at increased risk for unsafe driving.[8] Other studies using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment(MoCA) were less consistent, some suggesting a cutoff of MoCA score ≤ 25. In contrast, larger studies could only specify MoCA ≤ 18 as a cutoff for patients likely to fail on-the-road testing.[16][17] A more recent systematic review did not find a consistent relationship between cognitive testing and driving performance.[7] Testing patients with a validated composite battery of neuropsychological tests may provide an overview of the patient’s function level but may not be clearly predictive of driving ability.[18]

A caregiver’s impression of the patient’s driving safety has proven to be more indicative of driving impairment, and it is often more accurate than the patient’s own individual self-assessment.[15] Corroborating driving history with the caregiver carries Level B evidence to support its utilization. Other professional assessments, such as occupational therapy evaluations, may prove beneficial, though these assessments cannot predict how long a patient will maintain that assessed driving function level.[4] Driving rehabilitation therapists are trained to complete a multi-hour assessment with on-the-road testing that can provide information on the technical skills.[4] Some state agencies and insurance companies provide online algorithms and required driving tests to assess how well a patient operates a vehicle.[4][15] There may also be state-specific mandated reporting laws, so being familiar with each state’s regulations is important.

Triaging patients with these screening tests is important in guiding clinical recommendations.[17] Driving impairment is prevalent and is likely underreported among patients with dementia, so patients and families should be counseled on driving safety early in the disease course.[3] Clinical symptoms, objective on-the-road testing, and caregiver assessments should help guide the decision towards driving retirement. This is a dynamic assessment, as patients with neurocognitive disorders may need frequent re-evaluation with disease progression.[8]

Other Issues

The relative advantages and disadvantages of driving assessments based on road tests, simulations, or naturalistic data remain unclear. Further research is needed to identify predictors of higher risk for motor vehicle crashes.[19]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Given the high emotional stakes with discussing and determining driving privileges, it is better to begin this discussion early in the course of dementia before overt impairment is noted.[4] This allows patients to anticipate the impact of driving restrictions while still having insight without immediately taking away their sense of control. Maintaining control is a key factor in a patient’s self esteem, and loss of control in everyday tasks is often associated with psychological decline.[9] Instead, the clinician and caregivers should focus the discussion on transitioning to safe transport and becoming a safe passenger.[4] Avoiding the language of “withdraw,” “take away,” and “loss of privilege” can aid in effective patient communication without making the patient feel victimized or at fault.

After providing the driving fitness assessment, patients and families may need help complying with this new transition at home. Clinicians may suggest social resources or safer public transportation options.[17] Patients may continue to attempt driving despite their families’ warnings, and at this point, the patient's safety must be prioritized. Caregivers should be advised to avoid discussions that remind the patient of what they can no longer do. In some cases, families may need to park the car away from easy access or hide the car keys. Directly confronting the patient with repeated threats will likely increase a patient’s confusion and compromise safety at home. Instead, families should be encouraged to de-escalate by changing the topic of discussion discussion topic or distracting the patient until they are less focused on driving.[4] Patients and families may benefit from participating in driving cessation groups in the community to aid the transition.

In summary, patients with dementia are at increased risk of driving impairment and their fitness to drive should be evaluated in all patients with neurocognitive disorders. There is no single objective scale or test to determine driving fitness, so this decision should involve a multidisciplinary assessment. It is prudent to begin screening for driving impairment as soon as the clinician obtains a history of driving accidents/citations or significant changes in driving patterns. This should be followed with a thorough evaluation of the patient’s medications and physical exam. If patients have high-risk features of cognitive decline on screening, they should be further evaluated with neuropsychological testing and the clinical dementia severity scale (Level 1A evidence).

Due to the complexity of CDR scoring, clinicians in a busy practice may consider utilizing the MMSE or MoCA as an alternative. They should consider the lack of Level 1A evidence supporting their use in assessing driving ability. The next step in any safety assessment can include referring the patient to a certified occupational therapist or a driving rehabilitation specialist to assess on-the-road driving abilities. Using this stepwise diagnostic approach may provide a comprehensive evaluation of the patient and driving safety. After a patient has been deemed unfit to drive, it is the clinician’s responsibility to share this information sensitively with the older adult and ensure that the patients and caregivers are well-supported in this important transition. Additionally it is important that this information has also been well documented so other team members involved in the patients care are informed and aware.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Gómez-Gómez ME, Zapico SC. Frailty, Cognitive Decline, Neurodegenerative Diseases and Nutrition Interventions. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Jun 11:20(11):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112842. Epub 2019 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 31212645]

Dubinsky RM, Stein AC, Lyons K. Practice parameter: risk of driving and Alzheimer's disease (an evidence-based review): report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000 Jun 27:54(12):2205-11 [PubMed PMID: 10881240]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLee L, Molnar F. Driving and dementia: Efficient approach to driving safety concerns in family practice. Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 2017 Jan:63(1):27-31 [PubMed PMID: 28115437]

Hamdy RC, Kinser A, Kendall-Wilson T, Depelteau A, Whalen K, Culp J. Driving and Patients With Dementia. Gerontology & geriatric medicine. 2018 Jan-Dec:4():2333721418777085. doi: 10.1177/2333721418777085. Epub 2018 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 29900187]

Karthaus M, Falkenstein M. Functional Changes and Driving Performance in Older Drivers: Assessment and Interventions. Geriatrics (Basel, Switzerland). 2016 May 20:1(2):. doi: 10.3390/geriatrics1020012. Epub 2016 May 20 [PubMed PMID: 31022806]

Alonso AC, Peterson MD, Busse AL, Jacob-Filho W, Borges MTA, Serra MM, Luna NMS, Marchetti PH, Greve JMDA. Muscle strength, postural balance, and cognition are associated with braking time during driving in older adults. Experimental gerontology. 2016 Dec 1:85():13-17. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.09.006. Epub 2016 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 27616163]

Bennett JM, Chekaluk E, Batchelor J. Cognitive Tests and Determining Fitness to Drive in Dementia: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2016 Sep:64(9):1904-17. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14180. Epub 2016 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 27253511]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceToepper M, Falkenstein M. Driving Fitness in Different Forms of Dementia: An Update. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2019 Oct:67(10):2186-2192. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16077. Epub 2019 Aug 6 [PubMed PMID: 31386780]

Radue R, Walaszek A, Asthana S. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2019:167():437-454. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00024-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31753148]

Cohen JA, Verghese J. Gait and dementia. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2019:167():419-427. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00022-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31753146]

Lenardt MH, Lourenço TM, Betiolli SE, Binotto MA, Sétlik CM, Barbiero MMA. Handgrip strength in older adults and driving aptitude. Revista brasileira de enfermagem. 2022:76(1):e20210729. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2021-0729. Epub 2022 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 36449971]

Brown LB, Ott BR, Papandonatos GD, Sui Y, Ready RE, Morris JC. Prediction of on-road driving performance in patients with early Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005 Jan:53(1):94-8 [PubMed PMID: 15667383]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDuchek JM, Carr DB, Hunt L, Roe CM, Xiong C, Shah K, Morris JC. Longitudinal driving performance in early-stage dementia of the Alzheimer type. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003 Oct:51(10):1342-7 [PubMed PMID: 14511152]

Grace J, Amick MM, D'Abreu A, Festa EK, Heindel WC, Ott BR. Neuropsychological deficits associated with driving performance in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society : JINS. 2005 Oct:11(6):766-75 [PubMed PMID: 16248912]

Iverson DJ, Gronseth GS, Reger MA, Classen S, Dubinsky RM, Rizzo M, Quality Standards Subcomittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter update: evaluation and management of driving risk in dementia: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010 Apr 20:74(16):1316-24. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181da3b0f. Epub 2010 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 20385882]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHollis AM, Duncanson H, Kapust LR, Xi PM, O'Connor MG. Validity of the mini-mental state examination and the montreal cognitive assessment in the prediction of driving test outcome. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2015 May:63(5):988-92. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13384. Epub 2015 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 25940275]

Hill LJN, Pignolo RJ, Tung EE. Assessing and Counseling the Older Driver: A Concise Review for the Generalist Clinician. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019 Aug:94(8):1582-1588. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.023. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31378232]

Esser P, Dent S, Jones C, Sheridan BJ, Bradley A, Wade DT, Dawes H. Utility of the MOCA as a cognitive predictor for fitness to drive. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2016 May:87(5):567-8. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2015-310921. Epub 2015 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 25986364]

Daffner KR, O'Connor M. It Is Time for Medicare to Cover Driving Safety Assessments. JAMA neurology. 2024 Aug 12:():. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2024.2461. Epub 2024 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 39133469]