Doppler Trans-Cranial Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Doppler Trans-Cranial Assessment, Protocols, and Interpretation

Introduction

Transcranial Doppler (TCD) is a non-invasive ultrasound technique, not utilizing ionizing radiation. This technique takes advantage of acoustic windows present in the skull to interrogate the intracranial vascular structures. Various vascular measurements can be determined, including cerebral blood flow velocity, which can affect many different pathologies. Common indications for TCD include screening for vasospasm in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage, screening for signs of angiopathy in pediatric sickle cell disease patients, and evaluation for a right-to-left shunt in the setting of stroke and suspected paradoxical embolism (patent foramen ovale and other pathologies).[1] This article will focus on these common indications.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The intracranial arteries are supplied by the vertebral and the bilateral internal carotid arteries. These extracranial vessels supply the Circle of Willis, named after Thomas Willis, an English physician. The Circle of Willis is an anastomotic ring of vessels that supply the brain. The anterior circulation is largely provided by the ICAs, which branch intracranially into the middle cerebral and anterior cerebral arteries. The posterior circulation is supplied by the vertebral arteries, which join to form the basilar artery. The basilar artery gives off distinct branches, including the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA), pontine perforating arteries, and the superior cerebellar arteries. The basilar artery then bifurcates into the bilateral posterior cerebral arteries. The circle is completed via connections of the distal ICAs to the PCAs via the posterior communicating arteries, and the bilateral ACAs are connected via the anterior communicating artery.[2] There are numerous variations to this classic anatomy, many of which cause an incomplete circle. Segmental hypoplasia or aplasia is common, with a complete circle of Willis observed in less than 20% of the population.[3]

The internal carotid artery can be broken down into multiple segments, typically C1-C7 based on a classification system by Bouthillier et al. While there is no universally accepted naming system of the carotid segments, the one by Bouthillier is the most commonly used.[4] The ICA originates at the common carotid artery's bifurcation as it splits into the external carotid and internal carotid arteries. This travels superiorly to the carotid canal of the petrous bone and bifurcates intracranially as the MCA and ACA vessels. The C1 segment is considered the cervical segment, extending from the ICA origin to the carotid canal. Often, the intracranial portion of the ICA is referred to as the carotid siphon. This terminology is based on angiographic studies by Moniz in 1927. Still, it roughly correlates with the C2 (Petrous), C3 (Lacerum), C4 (Cavernous), and C5 (Clinoid) segments based on the modern classification system as the artery makes multiple bends through the petrous bone.[5] The final carotid segments are C6 (Ophthalmic) and C7 (Communicating).[6]

Vasospasm

While the cause of vasospasm is not definitely identified, one potential cause is decreased production and decreased response of the artery to the vasodilator, nitric oxide. After a subarachnoid hemorrhage, the incidence of vasospasm usually occurs between days 4 and 14. Detection of vasospasm is important in a subarachnoid hemorrhage patient because of its association with delayed cerebral ischemia. Traditionally, vasospasm has been treated with "Triple H" therapy which included hypertension, hypervolemia, and hemodilution. However, this is no longer the mainstay treatment for vasospasm, with multiple newer treatments, including hypertension in a euvolemic patient, among others. Delayed cerebral ischemia is important to identify and treat, contributing to the high morbidity and mortality of subarachnoid hemorrhage patients.[7]

When there is a decrease in the diameter of a segment of a vessel (as in vasospasm), there is an associated increase in velocity and decrease in pressure. This is based on Bernoulli's principle and is because the same volume of blood is trying to cross this narrowed vessel. To do this, the velocity increases. This fact is irrespective of the cause of the narrowing, be it from vasospasm, atherosclerotic disease, or other causes. This focal elevation in the velocity is the primary abnormality of interest in the interpretation of transcranial Doppler exams.[8] One potential pitfall in TCD examination is elevated velocity secondary to hyperdynamic states, such as in classic triple H therapy. To help with this pitfall, the Lindegaard ratio can be used to determine true vasospasm (discussed later).

Indications

Transcranial Doppler can be utilized for many different indications. There are, however, three main/common indications for using TCD, including monitoring for evidence of vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage, evaluation for a right-to-left shunt in the setting of embolic stroke, and screening of pediatric patients with sickle cell disease at high risk for stroke.[9][10] There are many other potential uses for TCD including, but not limited to: estimating intracranial pressure, brain death, ICA occlusion, monitoring after neurosurgical procedures, and cerebral autoregulation testing.[11][8]

Contraindications

There are few contraindications for TCD examination. Some would include lack of sonographic window for evaluation and inability of the patient to remain still during the examination.

Equipment

TCD typically utilizes a low-frequency transducer (2 to 3 MHz).[12]

Personnel

A sonographer or physician trained in transcranial Doppler techniques is required.

Preparation

No specific patient preparation is required for a general TCD examination. For specific applications, there may be some additional preparation required. For example, the evaluation of right-to-left shunt utilizes a contrast examination. This requires the patient to have an IV line started (typically in an antecubital vein) attached to tubing with a three-way stopcock. Additionally, for this exam preparation, agitated saline will be needed.[13]

Technique or Treatment

Basics of Doppler Ultrasound

Doppler ultrasonography is based on a physics principle called the Doppler effect, first described in the mid-1800s by Christian Doppler. It describes how a sound wave frequency changes when it hits a moving object; in this case, a red blood cell is contained within a vessel. The ultrasound probe emits a soundwave with a known frequency; as this travels into the tissue and hits a moving red blood cell, the frequency changes as it reflects back to the probe. Based on this, the computer can determine the direction relative to the probe and the velocity of the moving red blood cell. Velocity measurements are also dependent upon the Doppler angle (theta). This is the angle between the direction of insonation and the direction of blood flow. For general vascular ultrasound, this angle should be less than 60 degrees.[8]

Basic Transcranial Doppler Exam

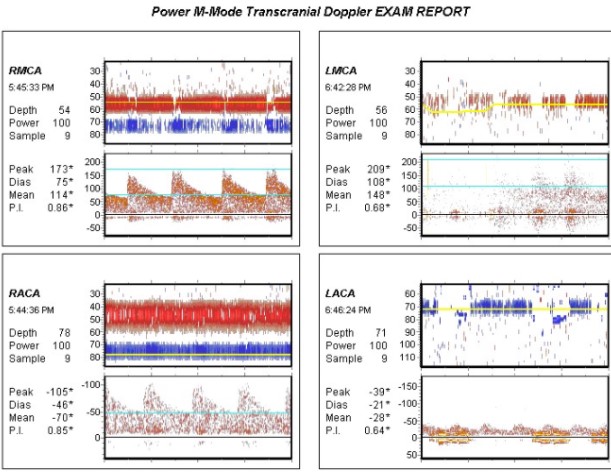

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound utilizes various principles to allow interrogation of intracranial vessels for various uses. Firstly, a low-frequency ultrasound probe is utilized (2-3 MHz) due to improved penetration through structures with low-frequency sound waves, in the case of TCD, the cranial bones. Classically, the power M-mode is utilized for common indications (although color Doppler can also be used). During insonation of the cranium identifying the vessels is dependent upon a few variables and knowledge of normal intracranial vascular anatomy. Identification is based on (1) Which Doppler window is being utilized, (2) the direction of flow relative to probe position, (3) the depth of the target vessel, and (4) the Doppler spectra.[14][15]

Insonation windows with depth and direction of flow for vessel identification:[15]

- Transtemporal:

- M1 branch MCA: Depth of 45-65mm with direction toward the probe.

- MCA/ACA bifurcation: Depth of 60-65mm with bidirectional flow.

- ACA: Depth of 60-75mm with direction away from the probe.

- PCA (P1): Depth of 60-75mm with direction toward the probe.

- PCA (P2): Depth of 60-75mm with direction away from the probe.

- Terminal ICA: Depth of 60-65mm with direction toward the probe.

- Transorbital:

- Ophthalmic artery: Depth 45-60mm directed toward the probe.

- Carotid siphon

- Supraclinoid: Depth 60-75mm directed away from the probe.

- Genu: Depth 60-75mm with the bidirectional flow.

- Parasellar: Depth of 60-75mm directed toward the probe.

- Transforaminal:

- Vertebral artery: Depth of 65-85mm directed away from the probe.

- Basilar artery: Depth of 90-120mm directed away from the probe.

Common parameters investigated:

- Mean cerebral blood flow velocity: Calculated using peak systolic velocity (PSV) and end-diastolic velocity (EDV) based on the following formula: [PSV + (EDV x 2)]/3[1]

- Resistive index: Measure of resistance to blood flow. RI = (PSV - EDV)/PSV[8]

- Lindegaard ratio (LR): The LR is a calculated value that normalizes the MCA velocity to the ICA. This is calculated by the mean velocity of the MCA divided by the mean velocity of the ICA. This ratio is important for differentiating hyperemia from true vasospasm on TCD study. The idea is if the patient has an elevated velocity on examination, this could be related to hyperemia causing increased velocity. If the MCA is increased at a higher proportion than the ICA, it indicates vasospasm as the source of the elevated velocity. A normal LR is considered < 3, mild vasospasm 3.0-4.5, moderate vasospasm 4.5-6.0 and severe vasospasm >6.0.[11]

Common values for velocity measurements related to arterial vasospasm:[8]

Middle cerebral artery:

Normal = MFV <120 cm/s, Lindegaard Ratio <3

Mild vasospasm = MFV 120-150 cm/s, Lindegaard Ratio 3-4.5

Moderate vasospasm = MFV 150-200 cm/s, Lindegaard Ratio 4.5-6.0

Severe vasospasm = MFV >200 cm/s, Lindegaard Ratio >6

Anterior cerebral artery: Vasospasm = MFV >80 cm/s

Posterior cerebral artery: Vasospasm = MFV >85 cm/s

Technique for right-to-left shunt evaluation

Before starting the procedure, an IV line should be started in one of the antecubital veins with a 3-way stopcock attached to tubing. Utilizing a head strap, bilateral TCD probes are used to insonate the MCA vessels utilizing the transtemporal windows. Once the bilateral MCAs are selected, agitated saline is prepared using 9mL saline and 1mL of air. One bolus is given, and the MCAs are monitored for microemboli ("hits" of noise related to echogenic microbubbles shunted to systemic circulation). Then, after a 5-minute delay, another bolus is given with the addition of having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver (potentially worsening shunting) after the full bolus is given.[13]

TCD in Sickle Cell Disease

TCD is used as a screening tool to determine stroke risk in pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. This screening method is based on the STOP trial, which used the time-averaged mean velocity of the MCA and distal ICA as parameters to determine the stroke risk. The time-averaged mean velocity (TAMV) is utilized for pulsatile flow and essentially measures the mean velocity over multiple heartbeats. For these studies, the highest TAMV of either the MCA or ICA is used to determine risk. Normal is considered <170 cm/s, conditional is assigned to TAMV of 170-199 cm/s and abnormal is considered >/= 200 cm/s.[16]

Complications

There are no specific complications associated with TCD. When using the transorbital approach, care should be taken to avoid excess probe pressure.

Clinical Significance

TCD allows for non-invasive interrogation of intracranial structures such as the vasculature. Since this technique is based on ultrasound imaging, it is non-ionizing and can be performed portably; therefore, it is a good option for ICU patients who need repeat testing, may be difficult to move, and clinical neurologic examination may be limited. In the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage, daily TCD testing can be performed to monitor for signs of vasospasm. This allows for prompt identification and treatment of vasospasm to prevent delayed cerebral ischemia.[11] Daily surveillance is often performed during the first two weeks following hemorrhage, including the time of peak vasospasm incidence. Detection of abnormalities with noninvasive testing may prompt subsequent invasive treatment, such as intra-arterial calcium channel blocker administration.[17]

Implications for Sickle Cell Disease

Based on the American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease, TCD is recommended as an annual screening exam for children with HbSS.[18] They also recommend regular blood transfusion for at least a year in patients with abnormal velocities (when feasible) to reduce stroke risk. One study found that before TCD, the incidence of overt stroke in children with SCD was 0.67 per 100 patient-years. After TCD was introduced, this was reduced to 0.06 per 100 patient-years.[19]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Transcranial Doppler is a technique that can be used in various ways for various indications. An important part of this is the technologist performing the exam. They are critical to deriving the benefit from this exam because if it is not performed properly and to the highest standard, patient outcomes will not be optimal. Clear and open communication between the technologist and the physician is also paramount for clear, precise, and effective results. To further improve patient outcomes, the technologist must understand critical results so the physician can be notified promptly and minimize delay in care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

D'Andrea A, Conte M, Cavallaro M, Scarafile R, Riegler L, Cocchia R, Pezzullo E, Carbone A, Natale F, Santoro G, Caso P, Russo MG, Bossone E, Calabrò R. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography: From methodology to major clinical applications. World journal of cardiology. 2016 Jul 26:8(7):383-400. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v8.i7.383. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27468332]

Nicoletto HA, Burkman MH. Transcranial Doppler series. Part I: Understanding neurovascular anatomy. American journal of electroneurodiagnostic technology. 2008 Dec:48(4):249-57 [PubMed PMID: 19203078]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHindenes LB, Håberg AK, Johnsen LH, Mathiesen EB, Robben D, Vangberg TR. Variations in the Circle of Willis in a large population sample using 3D TOF angiography: The Tromsø Study. PloS one. 2020:15(11):e0241373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241373. Epub 2020 Nov 3 [PubMed PMID: 33141840]

Bouthillier A, van Loveren HR, Keller JT. Segments of the internal carotid artery: a new classification. Neurosurgery. 1996 Mar:38(3):425-32; discussion 432-3 [PubMed PMID: 8837792]

Sanders-Taylor C, Kurbanov A, Cebula H, Leach JL, Zuccarello M, Keller JT. The carotid siphon: a historic radiographic sign, not an anatomic classification. World neurosurgery. 2014 Sep-Oct:82(3-4):423-7. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2013.09.029. Epub 2013 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 24056221]

DePowell JJ, Froelich SC, Zimmer LA, Leach JL, Karkas A, Theodosopoulos PV, Keller JT. Segments of the internal carotid artery during endoscopic transnasal and open cranial approaches: can a uniform nomenclature apply to both? World neurosurgery. 2014 Dec:82(6 Suppl):S66-71. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.07.028. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25496638]

Chugh C, Agarwal H. Cerebral vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia: Review of literature and the management approach. Neurology India. 2019 Jan-Feb:67(1):185-200. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.253627. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30860121]

Kirsch JD, Mathur M, Johnson MH, Gowthaman G, Scoutt LM. Advances in transcranial Doppler US: imaging ahead. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013 Jan-Feb:33(1):E1-E14. doi: 10.1148/rg.331125071. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23322845]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePurkayastha S, Sorond F. Transcranial Doppler ultrasound: technique and application. Seminars in neurology. 2012 Sep:32(4):411-20. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1331812. Epub 2013 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 23361485]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLau VI, Jaidka A, Wiskar K, Packer N, Tang JE, Koenig S, Millington SJ, Arntfield RT. Better With Ultrasound: Transcranial Doppler. Chest. 2020 Jan:157(1):142-150. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.08.2204. Epub 2019 Sep 30 [PubMed PMID: 31580841]

Bonow RH, Young CC, Bass DI, Moore A, Levitt MR. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography in neurological surgery and neurocritical care. Neurosurgical focus. 2019 Dec 1:47(6):E2. doi: 10.3171/2019.9.FOCUS19611. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31786564]

American College of Radiology (ACR), Society for Pediatric Radiology (SPR), Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU). AIUM practice guideline for the performance of a transcranial Doppler ultrasound examination for adults and children. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine. 2012 Sep:31(9):1489-500 [PubMed PMID: 22922633]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNicoletto HA, Boland LS. Transcranial Doppler series part v: specialty applications. American journal of electroneurodiagnostic technology. 2011 Mar:51(1):31-41 [PubMed PMID: 21516929]

Bathala L, Mehndiratta MM, Sharma VK. Transcranial doppler: Technique and common findings (Part 1). Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology. 2013 Apr:16(2):174-9. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.112460. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23956559]

Lupetin AR, Davis DA, Beckman I, Dash N. Transcranial Doppler sonography. Part 1. Principles, technique, and normal appearances. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 1995 Jan:15(1):179-91 [PubMed PMID: 7899596]

Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, Abboud M, Gallagher D, Kutlar A, Nichols FT, Bonds DR, Brambilla D. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Jul 2:339(1):5-11 [PubMed PMID: 9647873]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLink TW, Santillan A, Patsalides A. Intra-arterial neuroprotective therapy as an adjunct to endovascular intervention in acute ischemic stroke: A review of the literature and future directions. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2020 Aug:26(4):405-415. doi: 10.1177/1591019920925677. Epub 2020 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 32423272]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDeBaun MR, Jordan LC, King AA, Schatz J, Vichinsky E, Fox CK, McKinstry RC, Telfer P, Kraut MA, Daraz L, Kirkham FJ, Murad MH. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults. Blood advances. 2020 Apr 28:4(8):1554-1588. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019001142. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32298430]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEnninful-Eghan H, Moore RH, Ichord R, Smith-Whitley K, Kwiatkowski JL. Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography and prophylactic transfusion program is effective in preventing overt stroke in children with sickle cell disease. The Journal of pediatrics. 2010 Sep:157(3):479-84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.03.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20434165]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence